7 Kawa model

Main concepts and definitions of terms

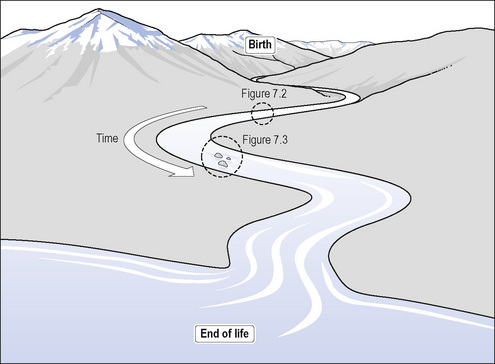

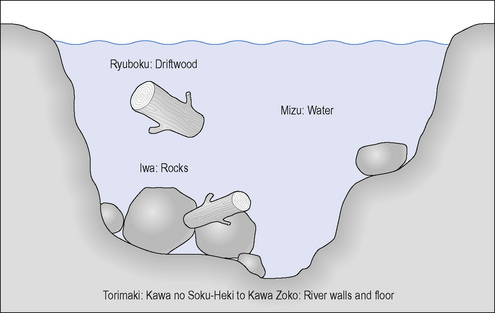

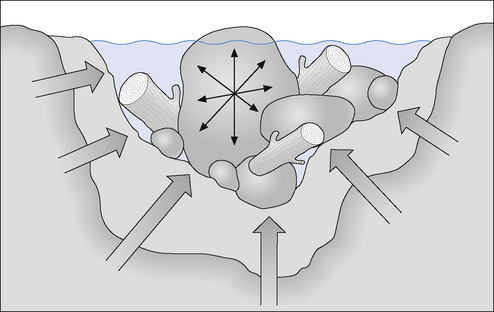

The Kawa model is structured around the metaphor of a river and its elements. It uses the image of the water flowing through a river to represent ‘life energy’ or ‘life flow’. In this model, the purpose of occupational therapy is to facilitate this life flow in the context of a harmonious balance with all aspects of the river. The river itself is used to describe a person’s life history (Figure 7.1) and cross-sections of the river at different times in the person’s history (Figures 7.2 and 7.3) can reveal the elements in the river. These elements are the river floor and walls, rocks, driftwood and the spaces between these. Each element represents an aspect of the person’s life circumstances. The water flows through the channels that are created by the relative positions and sizes of the other elements. Change can occur in the river by alteration of the position, size and shape of the elements to increase or decrease the flow of the water. This potential for change is the basis for occupational therapy intervention.

FIG 7.1 The river.

From Iwama, The Kawa Model (2006) Churchill Livingstone, with permission from Elsevier Ltd.

FIG 7.2 Elements of the river.

From Iwama, The Kawa Model (2006) Churchill Livingstone, with permission from Elsevier Ltd.

FIG 7.3 Elements constricting water flow.

From Iwama, The Kawa Model (2006) Churchill Livingstone, with permission from Elsevier Ltd.

The river is used to represent the flow or energy of life. It could refer to the life of an individual person, a family or the life of an organization (Iwama, 2006). In the metaphor of a river, the importance of context in shaping the river is emphasized. Rivers start because the moisture from rain and melting snow etcetera flows toward the lowest point of the land. Depending on the surrounding geography, rivers commence with varying amounts and types of water flow. They also flow towards lakes (some of which might be dry in lands such as Australia) and the sea. The course that the river takes depends on the unique combination of the surrounding geography, the strength of the river’s water flow and anything that lies in the river such as rocks and driftwood. Similarly, the flow of the water can vary in different parts of the river as variations occur in the unique combination of the quality of the water flow and other elements of the river.

In the Kawa model, the river is used as a metaphor for the life journey, with birth being represented by the start of the river and end of life being the point at which the river flows into a larger body of water such as the sea. As Iwama (2006) explained, “An optimal state of well-being in one’s life or river, can be metaphorically portrayed by an image of strong, deep, unimpeded flow” (p. 143). As a metaphor for life, the river shows that people’s lives are shaped by the unique contexts into which they are born and live as well as aspects of their own character and skill. Just as the river makes twists and turns, people’s lives change in a variety of ways. Some of these changes can be anticipated, some are unexpected, some are shaped by the surrounding context and others are primarily shaped by the flow of the water, which changes the shape of the river floor and walls. Sometimes the flow of people’s lives is impeded by obstacles and at other times everything seems to flow easily. Some people are born into or live in circumstances that flow easily like a wide river and others’ lives are characterized by obstacles that impact substantially upon their life flow.

Elements of the river

The first element in the Kawa model is the water. The element of the river used in the Kawa model to represent life energy or life flow is water, or mizu in Japanese. In many different cultures, water has symbolic meanings that relate to life. It is possible that water is a seemingly universal symbol of life because it is biologically essential for sustaining human life. Iwama (2006) highlighted that, while water is considered to be pure, cleansing and renewing and is often associated with the spirit, culturally specific meanings for water also abound throughout the world. He encouraged people to explore what water symbolizes in the particular cultures with which they might be engaging.

Water has a fluidity that allows it to flow over, around and through a range of different obstacles and channels in its path. As a fluid, it has the capacity to both shape and be shaped by whatever surrounds or contains it. It can take on the shape of a container but it also has the power to shape things that it flows over or through. For example, the erosion that occurs in rocks that are exposed to water attests to its power to shape its surroundings. As Iwama (2006) stated, “Just as people’s lives are bounded and shaped by their surroundings, people and circumstances, the water flowing as a river touches the rocks, walls and banks and all other elements of the river in a similar way to which the same elements affect the water’s volume, shape and flow rate” (p. 144). He also explained how important this mutually influencing relationship between the water and its surroundings is to understanding collective culture. He stated, “collectively oriented people tend to place enormous value on the self embedded in relationships. There is greater value in ‘belonging’ and ‘interdependence’, than in unilateral agency and in individual determinism. In such experience, the interdependent self is deeply influenced and even determined by the surrounding social context, at a given time and place, in a similar way to which water in a river, at any given point, will vary in form, flow direction rate, volume and clarity.” (p. 145.)

Water also has the capacity to fill the spaces between other things and only needs small spaces in which to flow. As a metaphor for life, this might suggest that life flow is possible in even the smallest of avenues. From the perspective of this metaphor, the task of an occupational therapist is to look at all aspects of the person’s context of daily life and facilitate greater life flow. “When life energy or flow weakens, the occupational therapy client, whether defined as individual or collective, can be described as unwell, or in a state of disharmony” (Iwama, 2006, p. 144). An occupational therapist can use any elements of the river (and their combinations) to work towards facilitating life flow.

The next concepts are the river walls and river floor. In the Kawa model, the river walls and river floor are referred to as kawa no soku-heki and kawa no zoko, respectively. Just as the walls and floor of the river shape the course, depth and width of the river, these parts of the river are used in the Kawa model to refer to the contexts that surround clients, that is, their social and physical environments. Iwama (2006) made the point that “these are perhaps the most important determinants of a person’s life flow in a collectivist social context because of the primacy afforded to the environmental context in determining the experiences of self and subsequent meanings of personal action” (p. 146).

Many of the examples of rocks provided in the major publication on the Kawa model (Iwama, 2006) relate to impairments of body structures and function such as low motivation, anxiety, depression and history of relapse – all symptoms and consequences of mental illness – and brachial nerve injury and pulmonary emphysema; while others relate to problems of performance such as difficulties with activities of daily living and self care. However, other rocks listed are money and human relations, which illustrate that obstacles in one’s life can relate to things other than impairments of body structure and function. Each person’s life circumstances and contexts of living are unique and will differ among people.

personal attributes and resources, such as values (i.e. honesty, thrift), character (i.e. optimism, stubbornness), personality (i.e. reserved, outgoing), special skill (i.e. carpentry, public speaking), immaterial (i.e. friends, siblings) and material (i.e. wealth, special equipment) assets and living situation (rural and urban, shared accommodations, etc) that can positively or negatively affect the subject’s circumstance and life flow. (Iwama, 2006, p. 149)

The utility of the concept of assets and liabilities lies in placing an emphasis on the fact that these attributes and resources can have a negative or positive effect on life flow. For example, Iwama (2006) provided a table listing examples of driftwood and, for each, positive and negative effects that each example might have on the life of an individual. Some of these are as follows: future expectations could have the positive effect of providing goals or something to look forward to, while potentially having negative effects by being a source of frustration, stress and worry; parents’ advantaged financial status could have the positive effect of assisting with equipment purchases and required home renovations while also possibly facilitating increased dependency and contributing to a lack of skill development on the part of the client.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree