Introduction to Therapeutic and Functional Stretching

Stiffness and restricted range of movement (ROM) are the most common clinical presentations second to pain. This book is for all therapists and individuals who would like to help others or themselves to recover or improve their ease and ROM. The book aims to provide the know-how to achieve this therapeutic goal with maximum effect.

What Is Stretching?

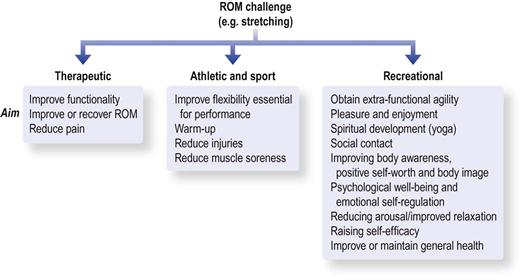

For the purpose of this book stretching is defined as the behaviour a person adopts to recover, increase or maintain their range of movement. This behaviour includes passive and active stretching, which can be in the form of exercise or with the assistance of another person (therapist/trainer). Stretching therefore is the means by which the ROM can be increased, but it is not the only one. There are several ways to achieve ROM improvements depending on the processes associated with the loss of ROM. ROM rehabilitation is perhaps a more suitable term to describe the therapeutic method used to recover/improve movement range. ROM challenge is the term given to all the different methods and techniques that are used to achieve this movement goal (Fig. 1.1).

Therapeutic, Sports and Recreational Stretching

Stretching behaviour can be observed in many spheres of human activity. It is often used in sports training as a warm-up, for prevention of injury and to improve sports performance. It is widely used by specialist groups such as athletes and yoga practitioners to develop the high level of flexibility required for performance/practice. Stretching is also used recreationally for general flexibility, enjoyment and self-awareness, as part of spiritual development, and for supporting health and well-being (e.g. yoga, Pilates and t’ai chi). Therapeutic stretching is used predominantly to help individuals to regain functionality that has been affected by ROM losses, and occasionally to alleviate pain (Fig. 1.2).

Therapeutic stretching, recreational stretching and sports stretching depend on the same biological–physiological processes to promote ROM changes. The differences are in their overall goals (recover ROM or feel great) and the context in which the ROM challenges are applied (in clinic or in a yoga class). The definition of stretching given above can also be used to define ROM rehabilitation or therapeutic stretching.

This book will focus on the therapeutic use of stretching and ROM rehabilitation. However, many of the principles discussed here can be applied to recreational and athletic stretching.

Is stretching essential for normalization of ROM?

It seems that only humans do it; that is, regular, systematic stretching. There is a shared animal and human behaviour of “having a stretch” and yawning called pandiculation. It is often a combination of elongating, shortening and stiffening of muscles throughout the body. Pandiculation tends to occur more frequently in the morning and evening and is associated with waking, fatigue and drowsiness.1 Erroneously, it is assumed that animals use pandiculation as a form of stretch. This behaviour is too short in duration, too infrequent and too specific to a particular pattern to account for general agility. It has been proposed that pandiculation may provide psychological and physiological benefits other than flexibility.1,2

Among humans, only relatively few individuals stretch regularly. Those who stretch tend to focus on particular parts of the body. For example, rarely is the little finger stretched into extension or the forearm into full pronation–supination. So what happens to the majority who do not stretch? Do they gradually stiffen into a solid unyielding dysfunctional mass? And what happens to the parts that we never stretch? Do they stand out as being stiff/range-restricted?

It seems that going about our daily activities provides sufficient challenges to maintain functional ranges; otherwise, we would all suffer from some catastrophic stiffening fate. This suggests that stretching is not a biological–physiological necessity but perhaps a socio-cultural construct. We stretch because it provides special flexibility, it is fashionable and enjoyable (for some), and some believe that it is essential for maintenance of healthy posture and movement. There may be other benefits to recreational stretching such as improving body awareness, positive self-worth and body image, psychological well-being, reduced arousal/improved relaxation, emotional self-regulation and raising self-efficacy.

However, the most important message from the discussion so far is that functional movement, the natural movement repertoire of the individual, is sufficient to maintain the normal ROM. It suggests that ROM rehabilitation, in its most basic form, should put an emphasis on return to pre-injury activities, whenever possible.

Is stretching useful therapeutically?

Recovering ROM becomes important when a person is unable to perform normal daily activities, often as a result of some pathological process that results in range limitation. So there is an obvious need for ROM rehabilitation, but the question is which ROM challenges are most effective?

It has been assumed for a long time that traditional stretching approaches can provide effective ROM challenges. This assumption was supported by numerous studies demonstrating that in healthy young individuals regular stretching results in ROM improvements. Since the biological processes for ROM improvements are similar to those for recovery, the logical conclusion was that stretching is clinically useful. However, only in the last decade has the use of stretching been explored clinically, as a treatment for contractures after joint surgery, neurological conditions and immobilization. The outcome of these studies was summarized in 2010 in a systematic review (35 studies with a total of 1391 subjects).3 It was found that in the short term stretching provides a 3° improvement, a 1° improvement in the medium term and no influence in the long term (up to 7 months). These findings were similar to all stretching approaches, active or passive. Let us assume for the sake of discussion that these reviewers underestimated the effects of stretching. Stretching will still be clinically irrelevant even if these results are doubled (6° and 2°) or tripled (9° and 3°).4 Such modest changes would be meaningless as far as functional activities are concerned;5 most patients (in my experience) would consider this outcome a treatment failure.

The erosion of belief in the usefulness of stretching is also seen in other areas. Stretching as a warm-up before and after exercising has failed to show any benefit for alleviating muscle soreness. It provides no protection against sports injuries and vigorous stretching before an event may even reduce sports performance.6–16 It was demonstrated that strength performance can be reduced by 4.5–28%, irrespective of the stretching technique used.17,18

One reason that stretching was not shown to be useful in all these areas may go back to biological necessity. If it was beneficial we would expect Nature to have “factored-in” stretching as part of animal behaviour, in particular if it improved performance. Yet, with the exception of humans, no animal performs any pre-exertion activities that resemble a stretch warm-up. Lions do not limber up with a stretch before they chase their prey, and reciprocally the prey does not halt the chase for the lack of a stretch. The stretch warm-up in humans seems to be largely ceremonial. A person would stretch in the park before a jog but would not consider stretching to be important for sprinting after a bus. A person may stretch before lifting weights in the gym but a builder is unlikely to stretch, although they may be lifting and carrying throughout the day. The point made here is that we have evolved to perform maximally, instantly and without the need to limber up with stretching. There seems to be no biological advantage in stretching nor is it physiologically essential.

The ineffectiveness of stretching leaves us with the clinical conundrum of how to recover ROM losses. We do know that most of the time people do recover their ROM losses after conditions such as immobilization, surgery, disuse and even frozen shoulder. If they do not do this by stretching, some other phenomenon must account for the recovery; but what is it and can it guide us to a more effective ROM rehabilitation?

Towards a Functional–Behavioural Approach

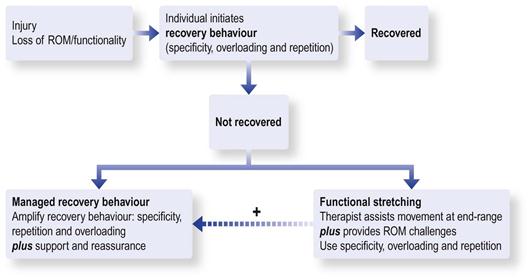

The place to start exploring the solution to ROM rehabilitation is the natural recovery behaviour seen after an injury or immobility. There seems to be a universal behaviour in which the individual will attempt to perform the affected movement in a guarded progressive manner. A person who has limited reaching ROM will attempt that same movement, gradually increasing the range of reaching, forces used to lift or speed of that particular movement. Through such behavioural experiences the individual learns that taking certain actions will eventually help them to achieve their movement goals. So the recovery of ROM is driven by the individual’s actions or behaviour.

Imagine if somehow “the essence” of the recovery behaviour could be extracted and provided to patients who are not improving naturally. The recovery behaviour contains three identifiable traits that are beneficial for improving ROM. The movement closely resembles the affected daily functional tasks and it is repeated many times throughout the day. The recovery behaviour also contains movements that are progressively amplified to provide increasing physical demands on the body. These components of the recovery behaviour are similar to the specificity, overloading and repetition principles used to optimize sports performance. Thus, a ROM rehabilitation programme can be constructed by simply amplifying these three traits. The management for a person with a shoulder problem who cannot reach overhead is to attempt this particular movement (specificity; Ch. 5), trying to reach further overhead (overloading; Ch. 6), many times during the day (repetition; Ch. 7). It is basically about performing functional activities with an emphasis on end-ranges. This form of ROM rehabilitation is termed managed recovery behaviour.

Managed recovery behaviour assumes that the patient is able to self-care and can maintain a rehabilitation programme. However, some patients may need assistance, a “helping hand” from others. In the assisted programme the essence of the recovery behaviour is still the guiding model. The therapist helps the patient to reach the end-ranges. In these positions the patient attempts to perform a variety of daily movements. For example, in shoulder contractures, the therapist helps the patient to attain a comfortable flexion position. At this angle, the patient is instructed to imagine and perform a functional activity, such as painting the ceiling or waving a flag.

The therapist-assisted form of ROM rehabilitation is termed, here, functional stretching (Fig. 1.3). The term functional stretching is used solely for its simplicity. Most practitioners, and more importantly patients, can understand its meaning and aims. This approach is discussed in greater detail in Chapter 12, and presented in Chapter 13 and the accompanying video.

FIGURE 1.3 Using elements from the recovery behaviour as a basis for a functional range of movement (ROM) rehabilitation (see expansion of this chart in Ch. 12).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree