Glenohumeral Arthritis

Glenohumeral arthritis may result in considerable disability. The impact of glenohumeral arthritis is comparable to chronic medical conditions such as congestive heart failure, diabetes, and acute myocardial infarction (1). In adults over the age of 60, the majority of glenohumeral arthritis is primary osteoarthritis and treatment algorithms are well defined with shoulder arthroplasty providing the mainstay of operative treatment. In this population, total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA) provides reliable pain relief and functional improvement with satisfactory implant longevity. However, for adults under the age of 60, and particularly for those under 50, diagnoses usually involve more complex pathology and arthroplasty outcomes are less predictable. Treatment decision-making factors that become more important in this young adult population include higher activity levels, greater functional expectations, and implant longevity. In addition, a subset of elderly patients may prefer a minimally invasive procedure that avoids the risks associated with TSA.

For these populations, a wide spectrum of glenohumeral arthritis pathology can successfully be managed arthroscopically. Current arthroscopic management techniques for glenohumeral arthritis include debridement and capsular release with biceps tenotomy or tenodesis, labral advancement, microfracture, and glenoid resurfacing. Additionally, an arthroscopic total shoulder replacement is on the horizon (see Chapter 25, “Future Developments”).

PREOPERATIVE EVALUATION AND INDICATIONS

While treatment decision making always requires detailed evaluation of the patient, there are several factors that are more commonly encountered in the younger patient with glenohumeral arthritis that take on increased importance. The etiology of glenohumeral arthritis differs in the young adult compared to the older adult, with younger patients often having diagnoses that are more complex and may result in poorer outcomes. In a study of 1,030 patients, Saltzman et al. (2) reported that primary osteoarthritis was present in 66% of patients over the age of 50 undergoing shoulder arthroplasty compared to only 21% in patients under the age of 50. Young patients were much more likely to carry diagnoses of capsulorrhapy arthropathy, posttraumatic arthritis, avascular necrosis, and rheumatoid arthritis. These diagnoses have been associated with worse functional results compared to arthroplasty for primary osteoarthritis (3).

In elucidating the history, particular attention is paid to social factors. While young patients often have few comorbidities, occupation and hobbies are important to consider. The manual laborer will place more stress on his or her shoulder and is more likely to loosen a polyethylene implant than a sedentary patient of the same age. Similarly, young athletic individuals may participate in sports that place greater demands on their upper extremities than the typical elderly patient.

Glenoid morphology and bone quantity affect outcome and are important to assess on an axillary radiograph. The primary osteoarthritis typical of the older patient population is characterized by cartilage loss and deformity involving both the humeral head and the glenoid. Younger patients are more likely to have traumatic arthritis and may exhibit asymmetric changes that involve only one side of the glenohumeral joint. Focal cartilage damage affecting a portion of an articular surface can also be seen. Thorough evaluation to determine the location and extent of arthritic change is therefore required in order to provide treatment that has a high likelihood of symptomatic improvement.

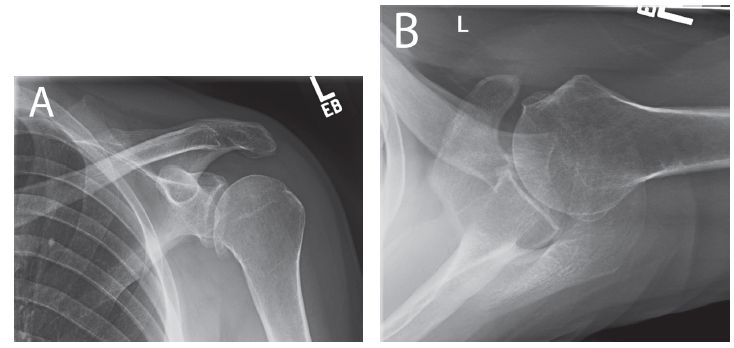

Figure 22.1 Left shoulder plain (A) anterior–posterior and (B) axillary radiographs in a 40-year-old man with primary glenohumeral arthritis. In this individual with stiffness and relative preservation of the joint space, an arthroscopic capsular release, osteophyte debridement, and biceps tenodesis are likely to provide substantial pain relief and delay the need for total shoulder replacement.

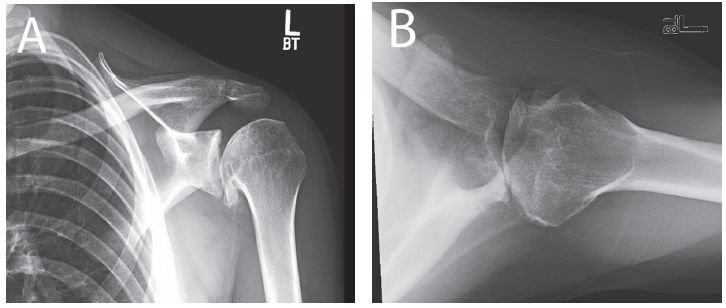

For elderly patients desiring a minimally invasive procedure, a capsular release, debridement, and biceps tenotomy or tenodesis can provide substantial pain relief in some cases. For young patients, treatment is based on the location of arthritis and the quality of the joint space. In patients with a relatively preserved joint space and stiffness, an arthroscopic capsular release and debridement alone often provides pain relief (Fig. 22.1). For isolated cartilage lesions, we perform microfracture or labral advancement based on the location of the lesion. For patients with a substantial loss of joint space, however, a biologic glenoid resurfacing procedure is indicated (Fig. 22.2).

Figure 22.2 Left shoulder plain (A) anterior–posterior and (B) axillary radiographs in a 22-year-old man with posttraumatic arthritis. Based on the extent of arthritis and decreased joint space, a capsular release alone is unlikely to provide substantial pain relief and a biologic glenoid resurfacing procedure is indicated.

CAPSULAR RELEASE AND GLENOHUMERAL DEBRIDEMENT

The expression “a stiff shoulder is a painful shoulder” is just as true in glenohumeral arthritis as it is in adhesive capsulitis. In the case of glenohumeral arthritis, patients present with capsular stiffness as well as impinging osteophytes that produce a painful mechanical block to motion. We have found that capsular release and osteophyte debridement can restore motion and reduce pain (4). It is our belief that a capsular release results in symptomatic relief by reducing joint contact pressures, particularly near the extremes of motion.

Technique for Capsular Release and Joint Debridement

The patient is placed in the lateral decubitus position and a diagnostic arthroscopy is performed through a posterior viewing portal. Anterior and anterosuperolateral portals are established. The stability of the biceps root is assessed with a probe introduced from an anterior portal. In most cases of glenohumeral arthritis, pathology of the biceps will be present in the form of degenerative tearing or disruption of portions of the biceps root. In elderly patients where cosmesis is not a concern, a biceps tenotomy can be performed at this time. However, in most cases, we prefer a tenodesis high in the groove. If a tenodesis is to be performed, we do this after the capsular release and debridement are completed.

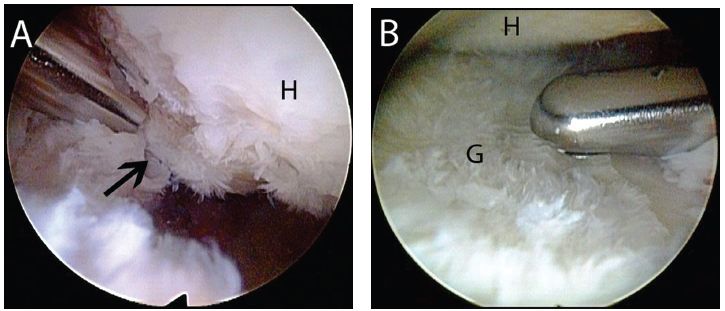

The arthroscope is moved to an anterosuperolateral viewing portal and the extent of any humeral osteophytes is assessed. A 70° arthroscope is often necessary for visualization as the typical location for humeral osteophytes is anteroinferior. A shaver is introduced through an anterior portal or a low anterior (5 o’clock) portal and is used to debride the anteroinferior humeral osteophytes (Fig. 22.3A). Care is taken during the debridement to preserve the humeral capsular attachments and avoid overaggressive resection, which could compromise stability. Any cartilage defects on the humerus and glenoid are debrided to a stable rim (Fig. 22.3B).

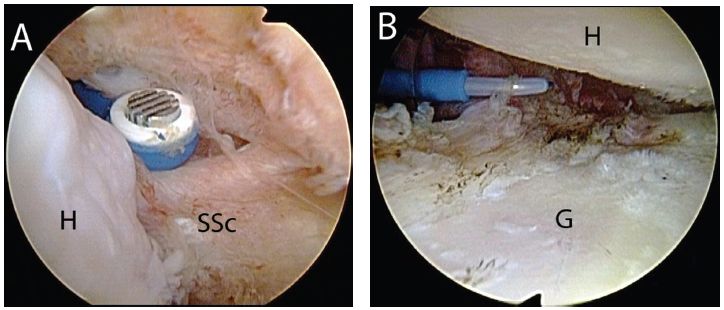

After the debridement is completed, a capsular release is performed as previously described (see Chapter 21, “Shoulder Stiffness”). Briefly, the arthroscope is returned to the posterior viewing portal and the rotator interval is released with an electrocautery introduced from the anterior portal (Fig. 22.4A). Then, the arthroscope is placed in the anterosuperolateral portal and the posterior, inferior, and anterior capsules are released 5 mm lateral to the labrum with a pencil-tip electrocautery (Fig. 22.4B). When the release is completed, the arm is removed from traction and a gentle manipulation under anesthesia is performed. The extent of the release is then confirmed arthroscopically.

Attention is then turned to the biceps, and a tenodesis is performed high in the groove as previously described (see Chapter 10, “The Biceps Tendon”) (Fig. 22.5).

ISOLATED CARTILAGE LESIONS

In addition to stiffness, young patients with a preserved joint space may demonstrate isolated cartilage lesions that can be treated with labral advancement or microfracture.

Labral Advancement

Small (<1 cm) glenoid cartilage lesions near the peripheral margin are amenable to labral advancement. The concept of labral advancement is to use the labrum to cover a symptomatic cartilage lesion to provide pain relief. We have used this technique with good to excellent outcomes at short-term follow-up in 90% of cases (5).

Figure 22.3 Right shoulder, anterosuperolateral viewing portal demonstrates debridement for glenohumeral arthritis. A: An anteroinferior humeral head osteophyte (blackarrow) is debrided with the use of a shaver. Because osteophytes are typically soft, a burr is not usually required for debridement. B: A shaver introduced through a posterior portal is used to debride glenoid chondromalacia. G, glenoid; H, humerus

Figure 22.4 Left shoulder demonstrating capsular release in a patient with glenohumeral arthritis. A: Posterior viewing portal. The rotator interval is released with an electrocautery. B: Anterosuperolateral viewing portal. A pencil-tip electrocautery introduced through the posterior portal is used to release the posterior, inferior (as seen in this figure), and anterior capsules. G, glenoid; H, humerus; SSc, subscapularis tendon.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree