14

Back School

| The Biomechanical Principles Of Back School | 321 | Standing | 326 |

| Sitting | 323 | Lying | 327 |

Back school (ryggskola in Swedish, Rückenschule in German) was introduced in Sweden in 1969 by Marianne Zachrisson-Forsell (1980) and Alf Nachemson. In subsequent years it has become the gold standard for rehabilitation and prevention of low back pain.

Back school is the training of proper posture and behavior for the prevention of injury to the back.

Back school is the training of proper posture and behavior for the prevention of injury to the back.

Underlying principle. As part of the rehabilitation and prophylaxis of spinal injuries, particularly disk diseases, patients do muscle-strengthening exercises and learn back-friendly methods of lifting, carrying, bending, sitting, standing, and lying. They also learn and practice the proper movements and bodily postures for a variety of everyday activities such as dressing and undressing, washing, and household chores. The subject matter to be learned consists, essentially, of three parts:

information about the structure and function of the spine

information about the structure and function of the spine

systematic training in the back school rules for lifting, bending, sitting, standing, lying, etc.

systematic training in the back school rules for lifting, bending, sitting, standing, lying, etc.

active protection of the spine through gymnastics and sports.

active protection of the spine through gymnastics and sports.

Information is imparted and demonstrations are given in group sessions, which are then supplemented with practical exercises. The target population for back training as a means of secondary prevention consists of patients who have been through an episode of disk disease and wish to avoid a recurrence. The teachings and exercises of back training are also used as primary prevention for individuals who have not yet had a bout of disk disease, but are at risk: children and adolescents with poor posture, adults with an invariant posture at work (sedentary occupation) and in their spare time, and all individuals with weak muscles.

The Biomechanical Principles Of Back School

The Biomechanical Principles Of Back School

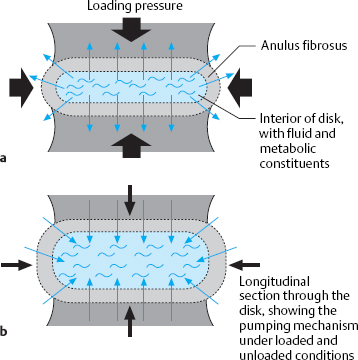

Activating the osmotic system of the disk (Fig. 14.1) (see Chapter 5). The pressure-dependent shifting of fluid into and out of the disk as an osmotic system is the basis of

Back school rule 1 (Table 14.1): Thou shalt exercise.

Back school rule 1 (Table 14.1): Thou shalt exercise.

The regular alternation of loading and unloading of the spine, through activities including sports and gymnastics, promotes metabolic exchange in the intervertebral disk.

| 1 | Thou shalt exercise. |

| 2 | Keep your back straight. |

| 3 | Kneel to bend. |

| 4 | Don’t lift heavy objects. |

| 5 | Spread out loads evenly, and keep them next to your body. |

| 6 | When sitting, keep your back straight and support your upper body. |

| 7 | Do not stand with straight legs. |

| 8 | When lying down, keep your legs bent. |

| 9 | Do sports, particularly swimming, running, or cycling. |

| 10 | Train your spinal muscles every day. |

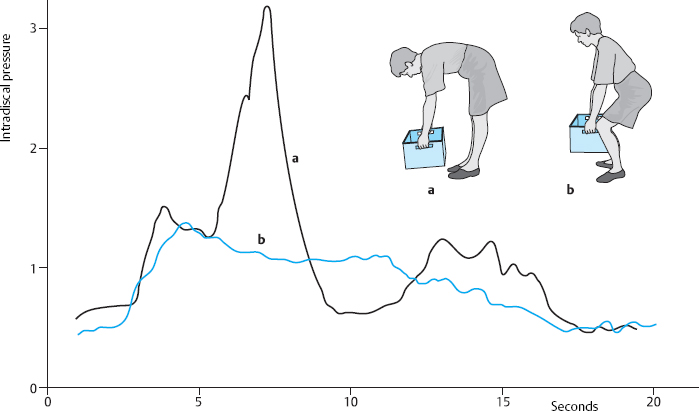

Avoiding excessive intradiscal pressure (Fig. 14.2) (see Chapter 5). As discussed in Chapter 5, experimental studies have shown that certain bodily postures and movements markedly elevate the intradiscal pressure. Back school teaches how these postures and movements can be avoided. Experimental studies and clinical observations both show that high intradiscal pressure, combined with asymmetrical loading of the intervertebral disk, leads to displacement of disk tissue and ultimately to disk protrusion and prolapse. Back school rules 2–6 are based on these biomechanical facts. The purpose of back school is to avoid increasing intradiscal pressure (Farfan 1996).

Fig. 14.1 a, b The intervertebral disk as an osmotic system.

a Load > 80kg: fluid and metabolic waste products are pressed out of the disk.

b Load < 80kg: fluid and nutrients are taken up into the disk.

Fig. 14.2 a, b Intradiscal pressure during lifting with a rounded back (a) and a straight back (b). Lifting with a rounded back causes a marked elevation of intradiscal pressure with a sharp peak (Nachemson 1966, Wilke 2004).

Fig. 14.3 Muscular stabilization of the lumbar motion segments by the muscles of the trunk and hips.

Avoiding telescoping of the intervertebral joints. Axial loading causes the lumbar intervertebral joints to become telescoped into one another. Lordosis and hyperlordosis augment this effect. The joint capsules are overstretched. This unfavorable situation can be counteracted by gently folding the legs (rules 7–8).

Building up the trunk musculature (Fig. 14.3) (see Chapter 5). Training of the abdominal, erector spinae, and proximal leg muscles stabilizes degeneratively slackened lumbar motion segments from without.

Sitting

Sitting

The stress-reducing effect of brief sitting. Sitting is wrongly considered to be generally harmful to the intervertebral disk. Many individuals suffering from low back pain are glad to be able to sit down for a short time after prolonged standing and walking, e.g., in a museum or while shopping. The deep and unbearable pain in the low back subsides immediately. The reason for this is that the hyperlordosis that sets into the lower lumbar motion segments after prolonged standing is flattened again when the individual sits, so that the intervertebral foramina become larger and the spinal canal becomes wider. That the lumbar motion segments are under reduced stress in this flattened or kyphotic posture is also demonstrated by the observation that the antalgic posture adopted by individuals with sciatica always includes a mild forward bending of the trunk.

Sitting with the hips and knees flexed and the lumbar lordosis neutralized restores the spine to the natural curvature that it had early on in ontogenetic development.

Sitting with the hips and knees flexed and the lumbar lordosis neutralized restores the spine to the natural curvature that it had early on in ontogenetic development.

The sitting position is also phylogenetically older than the erect posture, in which the hip joints are extended. Sitting abolishes all of the postural elements that were acquired along with the upright stance: lumbar lordosis, hip extension, and knee extension. The sitting position also corresponds to the stress-reducing step position, albeit with a 90° rotation, so that there is additional stress on the spine from gravity. A proper sitting posture is therefore crucial, so that spinal loading can be distributed evenly and held to a minimum.

There are three sitting postures, in which the center of gravity is located in front of, immediately above, or behind the sitting surface.

Sitting Forward

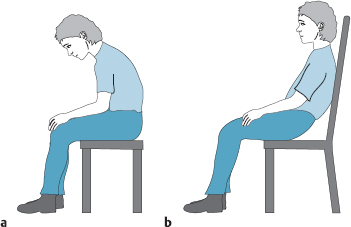

In the sitting-forward posture (Fig. 14.4 a), the intradiscal pressure is almost twice as high as during standing.

In the sitting-forward posture (Fig. 14.4 a), the intradiscal pressure is almost twice as high as during standing.

Increased loading of the anterior edge of the intervertebral disk, combined with high intradiscal pressure, leads readily to disk tissue displacement in a dorsal direction, i.e., to a protrusion or prolapse. According to the measurements of Andersson et al. (1974), the loading pressure on the disk is much lower when a individual sits upright with a flattened or lordotic lumbar spine than during sitting with a fully rounded back. It is of course possible to sit up actively from the sitting-forward posture, putting the lumbar spine into a lordotic position; this requires much truncal and muscular work, however, and can only be transiently maintained, because the lumbar spine normally assumes a kyphotic position when the hips are flexed to 90° and the pelvis is tilted backward (Fig. 14.4 a).

a The sitting-forward position: lumbar intradiscal pressure 0.65 MPa.

b The sitting-backward position: lumbar intradiscal pressure 0.3 MPa.

A backrest with a lumbar support was suggested as early as 1889 by Staffel as a means of counteracting maximal kyphosis and giving the spine its normal shape when the individual leans back (Staffel 1889). The beneficial effect is only brief, however, and then the lumbar support presses against the flattened or kyphotic photic lumbar spine at certain points. As Grandjean and Burandt (1962) observed, the desired correction also fails to occur when the individual, as usually happens, does not lean back properly or when the buttocks slide forward on the seat.

Sitting Back

The appropriate position for sitting is one that puts the least stress on the disks, ligaments, and muscles.

The appropriate position for sitting is one that puts the least stress on the disks, ligaments, and muscles.

As only lying down brings about a near-total unloading of all of these elements, individuals who must sit for a long period of time should attempt to sit in positions most closely approximating the lying position. Most individuals meet this requirement unconsciously by sliding forward in the seat while reclining the upper body backward, as long as the sitting surface offers enough room to do so. The final result is the extreme sitting-backward position with the pelvis tilted back (Fig. 14.4 b). This position is felt as pleasant at first, because the weight of the upper body is partly supported by the backrest. Nonetheless, if the backrest is high and close to the vertical, lack of lumbar support will lead to the development of a maximal kyphosis, not just of the lumbar spine but also of the cervical spine.

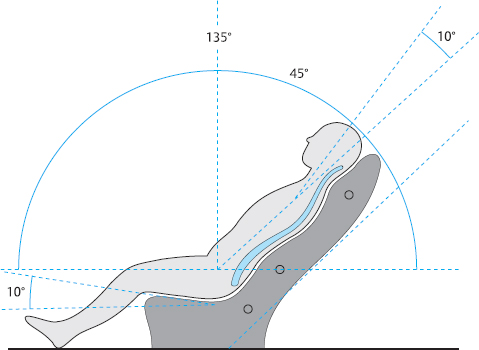

The stress-reducing sitting position. If, however, the backrest is shaped to correspond to the physiological curvature of the spine, and the head and neck are supported at a more favorable angle, then reclining to 45° results in a sitting posture that takes stress off the spine, ligaments, and muscles. The posture-maintaining work required of the cervical and truncal muscles is minimal in this stress-reducing position (Fig. 14.5). The loading pressure on the intervertebral disk is reduced in all portions of the spine. In the lumbar spine, it is less than 0.3 MPa and approximately equal to the loading pressure in the horizontal position (Nachemson 1974, 1976). Both Andersson et al. (1974) and Wilke (2001) showed that the loading pressure on the lumbar disks diminishes the more the backrest is reclined backward. A parallel lessening of activity in the trunk muscles was demonstrated electromyographically by Hosea and Simon (1984).

In the stress-reducing sitting position, the backrest should not be too soft, and it must have a mild protrusion at the lumbar and cervical levels corresponding to the somewhat flattened lordosis at these levels. As the ankle between the thigh and the truncal axis increases to 135°, lumbar support lessens the backward tilting of the pelvis. The main points of support are now at the thoracolumbar junction and in the craniocervical region. To give the seated individual a better viewing angle, the head is inclined 10–20° forward in relation to the truncal axis. The depth of the seat is adapted to the length of the thighs and its surface is inclined about 10° downward from front to back in order to keep the individual from sliding forward in the seat; a footrest may help achieve the same purpose.

One can use a 45° chair of this type to make the sitting position as much like the horizontal position as possible, not just during leisure hours but also during some types of occupational activity. This stress-reducing position can be obtained almost instantly with some kinds of adjustable easy chairs or TV loungers. It has also been found practical for driving (Krämer et al. 1979, 2005), as the low height of the seat above the floor of standard cars forces the driver to assume a sitting-backward position anyway. Any attempt to bring the spine into an upright position only leads to an even more pronounced lumbar kyphosis.

Guidelines for the sitting-upright position with a vertical spine were published by Akerblom (1948), Schoberth (1962), and Berquet (1984). According to these guidelines, the lumbar region should be firmly supported with a suitable backrest that reaches to the border of the pelvis. Chairs must have armrests so that some of the weight of the upper body can be laterally supported on the elbows at least some of the time, reducing the posture-maintaining work demanded of the shoulder and neck muscles. The proper depth of the seat depends on the length of the thighs, and the seat should be inclined downward about 5° from front to back. Writing desks should be of a height that the lower arms can be freely rested on the desktop without any need to raise the shoulders. The workplace, where many individuals spend a large part of their lives, must be adapted to individual body size, and this is best done with direct trials of the sitting position. Bad fitting of the workplace to the worker leads to the indefinite maintenance of harmful postures.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree