Abstract

Background

Physical exercise is widely prescribed in rehabilitation programmes for low back pain (LBP). The LBP patient often asks whether this physical activity should be maintained and, in some cases, whether he/she should resume or take up a sport.

Purpose

To answer these two questions by performing a review of literature on the efficacy and safety of post-rehabilitation physical activities and sport in LBP.

Method

A systematic search of computerized databases from 1990 to 2011 was performed using grade 1 to 4 studies articles in English or French.

Results

Of the 2583 initially identified articles, 121 articles were analysed. Globally, physical activities like swimming, walking and cycling, practiced at moderate-intensity help to maintain fitness and control pain. Inconsistent results were found for avoiding recommendations according to the nature of PA. Sport activities, except ballgames, can be easily resume or take up as tennis, horse riding, martial arts, gymnastics, golf and running which can be performed at a lower intensity or lower competitive level.

Discussion and conclusion

Moderate but regular physical activity helps to improve fitness and does not increase the risk of acute pain in chronic LBP patients. The resumption of a sport may require a number of adaptations; dialogue between the therapist and the sports trainer is therefore recommended.

Résumé

Introduction

L’exercice physique fait partie des programmes de restauration fonctionnelle pour les patients lombalgiques chroniques (LC). La question du maintien de l’activité physique (AP) et parfois de l’initiation ou de la reprise sportive est souvent posée par le patient.

Objectif

Répondre à ces deux questions par une revue de la littérature sur l’efficacité et la tolérance des AP et des sports chez le patient LC.

Méthode

Recherche systématique sur les bases de données en langue française et anglaise des résumés et articles (de niveau 1 à 4) de 1990 à 2011.

Résultats

Des 2583 articles identifiés, 121 ont été analysés. Les activités physiques modérées (de loisir, comme la nage, la marche, le vélo) contribuent à préserver la forme physique sans association évidente à un risque accru de récidive ou d’aggravation des douleurs lombaires. Pour les activités sportives, mis à part les jeux de ballon, le tennis, l’équitation, le judo et les arts martiaux, la gymnastique, le golf ou la course à pied peuvent être pratiquée à une intensité et à un niveau de compétition moindre.

Discussion et conclusion

Une activité physique modérée et régulière contribue à améliorer la forme physique et à mieux contrôler la douleur. La reprise sportive peut nécessiter des adaptations techniques et la collaboration entre le médecin et le professionnel du sport est alors souhaitable.

1

English version

The value of multidisciplinary functional rehabilitation programmes (FRPs) in the management of chronic low back pain (LBP) is now well established . These programmes include:

- •

personalized self-rehabilitation exercises for the spine;

- •

the implementation of appropriate ergonomic measures for the patient’s personal and professional environments;

- •

training on how to deal with pain flare-ups;

- •

fitness training. Patient education programmes that incorporate FRPs have demonstrated the benefits of regular physical exercise and help patients to commit to these activities .

Although continuation of physical exercise is considered to be beneficial , the poor compliance observed in this population means that long-term benefits cannot be guaranteed .

Moderate to intense physical activity 3 to 5 times a week has a positive influence on health and LBP . Hence, LBP patients are advised to resume their everyday activities because the latter are weak – to moderate-intensity activities that have health benefits when performed regularly . Being physically active improves the subject’s physical condition, decreases the risk of LBP and helps him/her to recover his/her previous level of fitness more easily . However, lifting and carrying loads and stressful activities with flexional or rotational work are known risk factors for LBP and, in theory, cannot be considered to be beneficial in chronic LBP patients. In contrast, leisure exercise, sport and physical activity are not associated with a risk of occurrence of LBP . Some researchers have even demonstrated the positive effects of exercise intensity, training volume and the type of exercise (strength training) on the course of LBP .

Sport (in terms of both leisure activities and competitive sport ) has not been covered in the main reviews on physical activity and chronic LBP published to date or in the European guidelines . The review recent by Heneweer et al. focused on the relationship between LBP and stresses related to physical activity (work, standing up, lifting a load, etc.) . According to the researchers, intense sport and (unspecified) leisure physical activities are associated with only a moderate risk of LBP.

Patients with LBP often put the following two questions to their therapist. Which physical activities are beneficial and which sports can be continued without running the risk of harmful effects?

Here, we performed an exhaustive, critical review of the literature in order to determine the advice that can reliably be given to an LBP patient after an FRP in terms of firstly, the benefits of a leisure physical activity and secondly, the absence of harmful effects related to resumption of a sport.

1.1

Method

We systematically searched computerized databases (Pubmed, Science Direct and the Cochrane Library) using the following keywords: low back pain, lumbar spine, trunk [and] physical activity, sport, soccer, tennis, horse riding, riding, equestrianism, judo, martial arts, tai chi, taekwondo, gymnastics, golf, walking, running, jogging, cycling, swimming, handball, basketball. Articles in French and English published between 1990 and 2011 (inclusive) were eligible for selection.

Chronic LBP was defined according to the Paris Task Force’s statement (recurrent pain in the lumbar region for at least the three previous months). Pain may be accompanied by radiation to the buttocks, the iliac crest or even the thigh but only very rarely goes below the knee .

We drew a distinction between physical activities and sports, in line with the World Health Organisation (WHO)’s definitions summarized by the Inserm . According to the WHO, physical activity is defined as any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that require energy expenditure over the basal metabolic rate . Next, physical exercise and sport lie on a continuum that ranges from inactivity to moderately intense activities (e.g. brisk walking) and then very frequent, intense activities (competitive sports). Sport is a subset of physical activity, specialized and organized as exercise or competition, often involving organizations (clubs). Physical exercise can take place in several different contexts. We limited our review to leisure physical activities and sports.

Most research has focused on adult populations. We examined:

- •

the physical activities that are most commonly suggested after FRPs for back pain in France (swimming, cycling and walking);

- •

tai chi (frequently suggested in south-east Asia and China);

- •

the six most widely played types of sport in France, according to the numbers of licensed club members in 2011 (football and other team sports, tennis, horse riding, judo and other martial arts, gymnastics [including soft gymnastics, aerobics, etc.] and golf).

The following selection criteria were used:

- •

prospective or retrospective longitudinal studies, case-control studies or observational studies;

- •

study populations with non-specific LBP for at least the previous three months;

- •

measurement criteria that included at least an evaluation of pain levels, the impact on the subject’s everyday life (physical activity, function, psychological status, quality of life, etc.), professional activities (absenteeism) or (in some cases) sporting performance;

- •

in the absence of data in on LBP populations, we analyzed articles providing data on biomechanical factors and/or of motor control motor related to the sport or physical activity in question and that could potentially be extrapolated to the context of LBP. Similarly, articles that established a link between physical or sporting activities on one hand and damage to the lumbar spine in the healthy subjects were selected when no data on LBP patients were available. The goal was to provide the reader with data for his/her consideration.

Each article’s references were analyzed as a function of their relevance. For each article, we analyzed the study design, study population, type of intervention, evaluation criteria, participant selection criteria, methodological quality, clinical pertinence, data extraction and level of evidence.

The critical review was performed by AD and AR by selecting only level 1 to 4 studies (grades A to C) according to the guidelines issued by the French National Authority for Health ( Haute Autorité de santé ) : grade A (strong scientific evidence) is based on meta-analyses of well-powered, randomized, controlled trials or the trial results themselves. Grade B (moderate scientific evidence) is based on the results of under-powered, randomized, controlled trials, non-randomized controlled trials or cohort studies. Grade C (low levels of scientific evidence) is based on case-control studies (level 3), retrospective studies or case reports (level 4). In the event of disagreement between the two reviewers, a third researcher (EV) decided whether to select the article or not by applying these above-mentioned criteria.

1.2

Results

1.2.1

Description of included studies

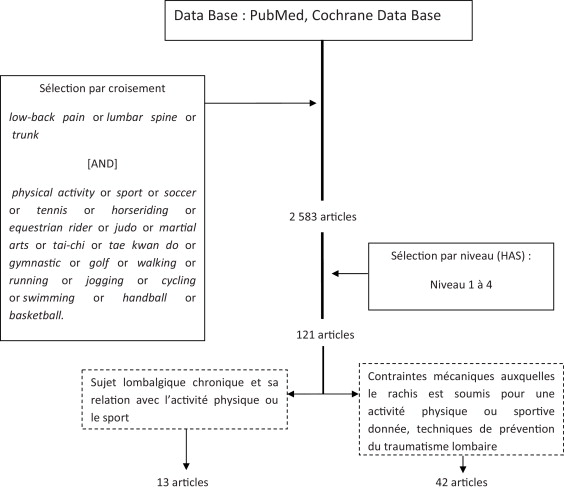

Our keyword search identified a total of 2583 articles, of which 88 met our quality criteria and were selected for review . A further 85 articles were identified by examining the 88 articles and their reference lists. In all, 121 articles were reviewed ( Fig. 1 ).

However, only 13 of these articles were related to the two key questions posed by the LBP patient with respect to physical activity and sport. The other articles dealt with the relationships between back injury on one hand and intense or high-level sporting activity on the other. The main results are presented in Table 1 .

| Authors, year | Type Level | Intervention | Evaluation | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burdorf et al. 1996 | Cohort study Level B | Golf A one-year follow-up of 196 male golfers High proportion of athletes (68%) | Specific questionnaire exploring occupation, sports (intensity), and back pain (VAS) | After 12 months, the incidence of first time back pain was 8% and the incidence of recurrent back pain was 45% |

| Håkanson et al. 2009 | OS Level C | Riding Equine-assisted therapy (EAT) for 6 weeks to 12 months | Pain (VAS) Well-being (?) | Improved well-being and reduced pain levels |

| Hall et al. 2011 | RCT Level B | Tai chi Group 1 ( n = 80): 2 tai chi sessions (40 minutes) per week for 8 weeks, 1 tai chi session/week for 2 weeks Group 2 ( n = 80): no tai chi | Bothersomeness (0–10) on a numerical rating scale Pain Disability Index Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale SF-36 Coping strategies Questionnaire | Improvement of pain and disability outcomes in LBP patients with 10 weeks tai chi sessions |

| Hartvigsen and Morsø 2010 | RCT Level B | Brisk walking Group 1 ( n = 45): Nordic walking twice a week for eight weeks, under supervision Group 2 ( n = 46): unsupervised Nordic walking after a training session with an instructor Group 3 ( n = 45): a one-hour motivational talk | Low Back Pain Rating Scale Patient Specific Function Scale Quality of life (EQ-5D) Medication intake | No significant difference but the 2 groups with Nordic walking tended to use less pain medication (no difference between supervised or non-supervised) No negative side effects |

| Parziale 2002 | Retrospective study Level C | Golf 145 golfers Intervention = modification of golf swing technique (83%) but also medical or surgical treatment (89%), physical rehabilitation, including exercises and diathermy (92%) | Injuries incidence Return to sports | Low back pain most frequent injury in golf Return to sports in 98% of subjects |

| Saraux et al. 1999 | OS Level C | Tennis Interview of 633 adults (421 men and 212 women) divided into tennis players (398) and controls (245) | LBP (pain VAS) Time spent playing tennis | Prevalence of LBP Tennis players: men = 17.4%, female = 18.7% Controls: men = 18.6%, female = 27.6 No significant difference |

| Sculco et al. 2001 | RCT Level B | Brisk walking and cycling Group 1 ( n = 17) = 10-week exercise program of aerobic exercise (AE) (walking or cycling at 60% of the age-predicted maximal heart rate, 4 days per week for 45 minutes per day) Group 2 ( n = 18) = no exercise | Brief Pain Inventory Profile of Mood States | With AE (walking or cycling) improvement of mood, no effect on pain, less pain medication |

| Taylor et al. 2003 | OS Level C | Fast walking LPB group ( n = 8) = 10 min walking at a self-selected speed and then 5 min fast walking on a treadmill Control group (8) = usual exercise | 3D video gait analysis Pain VAS | Walking fast does not increase pain in LBP |

| Turner et al. 1990 | RCT Level B | Brisk walking or running Group B ( n = 18) = Behavioural therapy with contribution from the spouse Group E ( n = 18) = Aerobic exercise (60% maximum heart rate, 20 min, 5 days a week), including fast walking or jogging Group BE ( n = 21) = the two interventions together Control group = nothing | McGill Pain Questionnaire Sickness Impact Profile Pain Behavior Checklist (the patient and his/her spouse) | The BE group improved between the pre- and post-treatment evaluations At 6 and 12 months of follow-up, each group had improved but there were no significant inter-group differences |

Articles dealing with the biomechanical loads and stresses to which the spine is subjected during a given physical or sporting activity or techniques for preventing injury (including the choice of equipment and techniques) were not excluded ( n = 42).

1.2.2

Benefits and risks of physical activities and sports for chronic LBP patients

1.2.2.1

Swimming

Given that swimming is an activity in which the participant’s bodyweight is fully supported, this activity is frequently recommended to LBP patients after an FRP. Aquatic exercises have demonstrated efficacy . However, the impacts of the various strokes in an LBP patient population have hardly been studied. From a biomechanical point of view, only butterfly stroke (requiring a more intense effort, with hyperlordosis and activation of the erector spinae muscles) is likely to promote the recurrence of LBP or even the occurrence of spondylolysis . We did not find any reports of an exacerbation of back pain for strokes other than butterfly. A case-control study comparing high-level swimmers and leisure swimmers did not find any difference in terms of the prevalence of the pain – regardless of the type of stroke . A greater observed prevalence of disc degeneration (L5/S1) in high-level swimmers suggested the presence of a relationship with training volume, training intensity and the number of years of training. The intensity and duration of effort can be easily modified and the range of available strokes (backstroke, breaststroke, crawl, etc.) and the fact that the body’s weight is fully supported means that the biomechanical stimulations can be easily modulated.

There is no proof that leisure swimming after an FRP increases pain levels (grade C). The observation of lower biomechanical loads during aerobic activity suggests (but does not prove) the presence of a beneficial effect. Butterfly should only be performed under supervision (grade C).

1.2.2.2

Walking

In principal, walking is the easiest means of performing physical activity.

A three-dimensional analysis of gait at different cadences in the healthy subject (based on the inverse solution approach) shows that the loads placed on the lumbopelvic region while walking are often lower than those in many activities of daily living, regardless of the cadence (with the exception of pelvic rotation, which is accentuated during brisk walking). Low-amplitude arm swings (i.e. during slow gait) tend to increase the “static” load on the lumbopelvic region, which becomes cyclic and thus better tolerated when amplitude of the arm swing is greater (i.e. during brisk walking) .

Sculco et al. randomized 35 chronic LBP patients into two groups: an exercise group, with 45-minute sessions of aerobic walking or cycling at 60% of the age-predicted maximum heart rate (HR max ) for four times a week for 10 weeks, and a control group in which the participants maintained their normal everyday levels of activity. The exercise group had significantly better mood and psychological status (relative to the controls) but there was no significant difference in perceived pain levels between the groups. Two years later, there was no inter-group difference in the frequency of medical consultations for pain. However, over the mid- to long-term, regular walking did not appear to be associated with new pain or the exacerbation of existing pain.

The results of a study by Taylor et al. showed that moderate levels of walking are beneficial in the routine management of acute LBP. The exercise consisted in walking on a treadmill for 10 minutes at a self-chosen speed and then (after a two-minute break) walking rapidly for 5 minutes. The researchers observed a decrease in pain immediately after the walking. Brisk walking did not lead to an apparent exacerbation of the symptoms. However, on the basis of a follow-up assessment at 6 weeks, it was not possible to say whether or not the decrease in pain was maintained over time.

In a literature review of just four sufficiently high-quality studies, Hendrick et al. concluded that there was enough evidence to state that walking was effective for chronic LBP. The low compression loads involved during walking and the cyclic nature of the movements, can improve disc nutrition the latter’s load-bearing capacity. However, aged-related disc degeneration may compromise this adaptation .

Nordic walking is especially popular in northern Europe and is performed by applying force to special walking poles with each stride (as in classic-style cross-country skiing). A prospective, single-blind, randomized study evaluated the effect of Nordic walking on function and pain levels over an 8-week period in a three groups of chronic LBP patients :

- •

a group that performed unsupervised Nordic walking after a session with an instructor;

- •

a supervised group with two sessions a week;

- •

a control group given advice on staying active.

The participants were assessed at 8 weeks, 6 months and 12 months. The functional and pain scores in the supervised Nordic walking group did not differ significantly from those of the other two groups. However, the mean improvement was greater in the supervised group. No harmful effects of Nordic walking were apparent .

Conclusions on walking in the LBP patient are contradictory (grade C). None of the types of walking are associated with adverse effects (grade B). In view of the low loads involved, regular walking (with or without poles) can be recommended (grade C).

1.2.2.3

Cycling

Leisure cycling appears to be a favoured means of promoting aerobic training. Although many studies have focused on the relationship between sports cycling and LBP, very few have looked at the positive or negative impacts of leisure cycling as a physical activity in the LBP patient.

In biomechanical terms, the cyclist’s seated posture implies the maintenance of lumbar kyphosis. The greater the proportion of bodyweight placed on the arms, the lower the total mechanical load on the spine. However, to reduce wind resistance, a cyclist must decrease his/her frontal surface area by flexing the thoracolumbar spine and the hips. This position increases the intradiscal pressure and thus accentuates the risk of LBP related to repeated or excessive spinal loading. The contraction of the lumbar paravertebral muscles is proportional to the pedalling cadense and is low in aerodynamic positions. The abdominal muscles are relaxed in all positions and at all pedalling cadenses. This imbalance can cause back pain in people lacking adequate physical preparation . Adjustment of the handlebar height, the saddle angle and the saddle’s distance from the handlebars and position relative to the bottom bracket axle have an influence on posture and spinal loading ( Fig. 2 ). When the saddle is positioned in front of the bottom bracket axle and the tip of the saddle lowered , lumbopelvic posture is improved and back pain incidence likely diminished.

In a cross-sectional study, back injuries were the fifth most prevalent injuries (30%) in leisure cyclists . In view of this high prevalence, Salai et al. demonstrated that the above-mentioned, simple technical adjustments could decrease the incidence and intensity of LBP in almost of 70% of the cyclists studied . Other than a demonstration of the beneficial effect of supervised cycling exercises , no studies have recorded a beneficial effect of leisure cycling in LBP patients.

Cycling may be beneficial for the LBP patient because it constitutes aerobic activity. The cycling position influences the spinal load and the requirement for technical adjustments (grade C). A “hybrid” or “town” bike should be recommended because the riding position is similar to that adopted on a mountain bike.

1.2.2.4

Tai chi

Although tai chi is not well known in the Western world, this non-contact martial art is very widespread in south-east Asia and China and can be employed as a physical activity in LBP. Only one study on this topic has been published.

In a cross-sectional study, Hall et al. divided 160 LBP patients (aged 18–70) into two groups: the interventional group ( n = 80), who received two 40-minute tai chi sessions a week for 8 weeks and then one session a week for two further weeks, and the control group ( n = 80), who continued to go about their everyday activities. In the tai chi group, the bothersomeness of back pain (measured on a 0–10 visual analogue scale) fell by 1.7 points and the pain’s intensity fell by 1.3 points. The self-reported disability (measured on the 0–24 Roland–Morris Disability Questionnaire scale) fell by 2.6 points.

Hence, tai chi had beneficial effects on persistent LBP, with a reduction in pain and the related disability (grade C). However, further research will need to confirm that practicing tai chi can be considered as a reliable, efficacious technique in chronic LBP.

1.2.2.5

Team sports

The incidence of the spinal injuries in team sports (soccer, rugby, handball, basketball, etc.) is low in (often young) professional players and is therefore less studied in amateur players.

Soccer is the most-played sport in France (with 1,641,283 licensed club players in 2011). Kicking is the moment of play that most involves the spine: spinal hyperextension during kick preparation and then sudden hyperflexion upon contact with the ball. Leisure football training (e.g. an hour twice a week) increases trunk activity and coordination. If the subject can react more rapidly to a sudden load, the spine is better stabilized and the risk of lumbar injury is lower (decreasing the trunk’s reaction time to load has a preventive effect on the occurrence of LBP) . In theory, soccer training has a favourable effect on LBP. However, intensive football practice in the adolescent is associated with a risk of LBP .

Rugby, handball and basketball are high-intensity sports in which physical contact between players is frequent. The movements are forceful, repeated and sudden. However, there are no studies on rugby, handball and basketball in a context of LBP.

Leisure football training may have a beneficial effect on lumbar coordination (grade C). Intensive football playing is not advisable and any resumption after an FRP should be progressive.

1.2.2.6

Tennis

In biomechanical terms, the tennis serve results from a combination of lumbar hyperextension, lateral bending of the trunk and shoulder rotation, followed by trunk flexion. Tennis players are prone to prolapsed discs (43%) . More generally, repeated microtrauma to the spine (repetitive rotational forces applied to the disc and coupled with hyperextension forces) increases the shear forces on the caudal lumbar discs and thus augments the risk of back problems . In fact, the quality of the technique, the intensity of the activity and the court’s surface appear to have decisive impacts on the occurrence of LBP . For example, a clay court has a soft, loose surface that limits load along the spinal axis, enables players to slide after a change in direction and thus decreases the shear forces on the vertebral discs.

It appears that LBP is a frequent problem in professional tennis players . A cross-sectional study has confirmed that the prevalence of back pain did not differ significantly when comparing 388 amateur tennis players and 245 controls . In contrast, there are no studies on LBP patients’ tolerance of playing tennis.

In view of the stresses described above, tennis appears to expose the player to additional risk of back injury (grade C). The resumption of tennis after an FRP and in the absence of supervision cannot be recommended. There is justification for not performing an overarm serve (at least temporarily) and for playing on a clay court (grade C).

1.2.2.7

Horse riding

Horse riding subjects the spine to compression forces and shear forces during both hyperextension and hyperflexion. The rider’s position on the saddle and the length of the stirrups influence the extent of lumbar lordosis . Decreasing the lumbar lordosis increases the stress on the muscles and ligamentous structures of the lumbar spine that work to maintain the body’s posture and balance. The proportion of the forces related to the horse’s movements that is transmitted to the rider varies as a function of the horse’s speed (walking, trotting or galloping) . Lumbar lordosis enables the rider to absorb the compression forces more easily. When the thighs are at an angle of 30–40° (relative to the horizontal), the lordosis lumbar is low. In this posture, the forces exerted on the discs and lumbar vertebrae exceed 65% of the rider’s bodyweight. If the stirrups are lengthened, the thighs can be at an angle of 45° and lumbar lordosis is maintained. Furthermore, this posture lowers the muscle and ligament tensions in the lumbar regions and hips. Use of longer stirrups also leads to a reduction in pelvic retroversion (which can be as high as 20° with short stirrups). Hence, so-called “western”, long-stirruped saddles are better suited to the maintenance of lumbar lordosis than short-stirruped English saddles ( Fig. 3 ).

Horse riding is one of the most dangerous leisure activities, with an injury rate of 35.7 per 100,000 riders. Back injuries (mainly bruising or muscle strains) account for 19% of these injuries . Indeed, back pain is one of the most frequent symptoms in competitive and professional riders, in whom the incidence of spinal pain is very high (72.5%) . There are no data on leisure riding. In an open, non-controlled study, Hakanson et al. studied the effects of equine-assisted therapy (EAT, which does not solely include horse riding) on 24 patients with chronic, invalidating LBP . The patients had already undergone a course of physiotherapy. The EAT programme included one or two individual or group sessions per week for periods of between 6 weeks and 12 months. The patients rode under the supervision of a physiotherapist and a riding instructor. A questionnaire was used to evaluate the EAT.

Hakanson et al. concluded that EAT relieved pain, decreased muscular stress and improved self-confidence, well-being, balance, mobility and posture. However, the study’s many sources of bias (an open design, an ill-defined interventional programme and evaluation of the results with a non-validated questionnaire) prevent firm conclusions from being drawn. Leisure riding may have beneficial effects in LBP patients and can be recommended (grade C). Use of a “western”, long-stirruped saddle should be recommended for biomechanical reasons (grade C).

1.2.2.8

Judo and other martial arts

Few studies have addressed the relationship between back pain and martial arts defined broadly and none have looked at the impact of performing these sports on LBP. However, all the available data show that the prevalence of LBP in martial arts performers is lower than in the equivalent age classes of the general population and the higher the rank obtained and the greater the frequency of training, the lower the prevalence of LBP.

1.2.2.9

Gymnastics

Artistic and rhythmic gymnastics, aerobics, acrobatics and tumbling expose the lumbar vertebral column to repeated hyperextensions; the prevalence of LBP in gymnasts has been estimated at between 30% and 85%. Rhythmic gymnastics is the most harmful for the spine . There are no studies on performance of gymnastics by LBP sufferers.

1.2.2.10

Golf

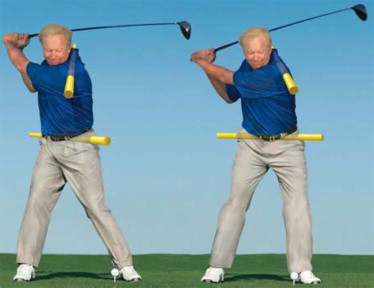

In golf, it is primarily the swing phase ( Fig. 4 ) that creates considerable load on the vertebral column, with anteroposterior shearing and compression during axial rotation and lateral bending. The trunk’s speed of rotation is very high (up to 200°/second) . Axial rotation has already been identified as a risk factor for back pain/injury, whereas the peak compression load is equivalent to eight times the bodyweight . Both “standard” and “modern” swing techniques lead to the same type of stresses: lateral bending, combined with rapid, high-energy rotation .

The incidence of golf-related lumbar injuries is between 15% and 34% in amateur golfers and between 22% and 24% in professionals. Overall, the incidence of LBP is 25% to 36% in male golfers and 22% to 27% in female golfers . In a one-year, prospective study of 196 golfers , the lifetime incidence of LBP was 63%, with incidence rates of 28% in the previous month and 8% at the end of study. Burdorf et al. did not find any evidence of an association between back pain and the frequency or duration of golf playing, although golfers with a history of severe LBP had a greater likelihood of relapse. However, 80.5% of the golfers with LBP did not consider that golf increased their pain levels .

Studies of possible predictors of LBP have identified a harmful role of a sub-10-minute warm-up, carrying the golf bag, repeated or intensive movements (more than 200 drives/weeks and more than 4 rounds a week) and poor swing technique . Modifying the technique can have a beneficial effect on chronic LBP. In one study, 145 LBP patients participated in a multidisciplinary golf rehabilitation programme based on correct grip and how to perform a standard swing with a shorter backswing (a 45° reduction in amplitude); 83% of the participants changed their swing techniques and 98% were able to resume golf at their previous level . In fact, use of a short backswing did not decrease golfing performance (i.e. there was no decrease in the speed of the head of the club upon contact with the ball) and protected the golfer’s lumbar spine by reducing the risk of back injury .

Golf can be recommended as long as the player warms up for at least 10 minutes, does not carry the golf bag and improves his/her swing technique (grade C).

1.2.2.11

Running

Running is a sport that involves repeated impacts. At heel strike, the lumbar spine bears a compression load of between 2.7 and 5.7 times the bodyweight .

The lifetime prevalence for LBP in runners is 75% . Footwear quality (cushioning, energy return, etc.) has a protective effect by decreasing shock transmission to the spine . Progressive training and smooth efforts also have a positive role .

In a randomized, controlled study, Turner et al. evaluated running as the primary intervention in 96 patients (aged 20–65) having suffered from chronic LBP for least 6 months . The 12-month study featured a control group and three interventional groups (behavioural therapy with aerobic exercise [BE]; behavioural therapy only [B] and aerobic exercise only [E]). Over an 8-week period, the BE and E groups performed five 10- to 20-minutes sessions of rapid walking or slow jogging per week (at 60–70% of HR max ) and received advice on warming-up and stretching. At 8 weeks, Turner et al. observed a significant improvement in the BE group (relative to the control group) in terms of pain intensity and physical functioning. At the end of the 12-month follow-up period, there were no significant differences between the three interventional groups in terms of self-assessed parameters (pain intensity, functioning, etc.) but there was still a significant improvement in all three groups relative to the control group. Moderate-intensity running does not accentuate LBP and even improves it significantly.

Intensive running appears be a risk factor for LBP (grade C). Regular, progressive training and the use of appropriate shoes and insoles that decrease shock transmission to the lumbar spine can be recommended for moderate running by LBP patients after an FRP (grade C).

1.3

Discussion

The objective of this review was to determine whether moderate physical activity after an FRP has beneficial effects and whether more intensive sporting activity has harmful effects. Most of the articles analyzed here were of mediocre quality, which restricted our ability to draw firm conclusions. In fact, most of the studies were either observational, combined several types of activity or levels of intensity and/or had questionable efficacy criteria. However, some of these articles did specify:

- •

the biomechanical or neuromuscular stress associated with the sporting activity;

- •

the recommended types of equipment and training sessions and the latter’s impact on the lumbar spine and LBP;

- •

proven means of preventing LBP (equipment, training and technique). Thirteen articles met our strict selection criteria (as specified in Section 1.1 ) and provided some relevant answers.

The leisure physical activities that one can reasonably suggest (swimming, walking and cycling with a hybrid/town bike) are essentially those generally (and empirically) recommended for maintaining fitness and flexibility after an FRP. These are aerobic activities that limit the vicious circle of detraining and may (in some cases) provide LBP patients with benefits (albeit in the absence of an explicit demonstration). One can recommend swimming (apart from butterfly), walking (including Nordic walking) and cycling (as long as hybrid/town bike is used and the saddle and handlebar positions are adjusted appropriately). Tai chi may be of value but is not yet commonly performed in Europe. Lastly, patients frequently ask about weight training and gym training but a lack of data prevented us from covering these activities.

Conclusions on the initiation or resumption of sporting activities are more contradictory – especially for sports that place loads on the lumbar spine (golf, horse riding, tennis, etc.). Likewise, a lack of data also prevented us from covering certain very popular but potentially harmful sports (ski, bowling, table tennis, etc.). In all cases, resumption of an activity must be progressive and must start at a very moderate level, with appropriately modified techniques and/or equipment, a personalized training schedule and close collaboration with a therapist.

However, controlling the intensity and volume of the physical activity or sport appears to be critical. In a cross-sectional study of 3364 adult LBP patients, Heneweer et al. showed that there was a continuum in the levels of intensity of physical activity and established a U-shaped curve describing the relationship between physical activity and back problems . In general, participation in a physical or sporting activity is not correlated with a lower prevalence of LBP. However, when subjects are stratified according to their usual level of overall physical activity, both high and low intensities of physical activity increase the risk of chronic LBP. This relationship was most significant in women, with an odds ratio (OR) [95% confidence interval (CI)] is 1.44 [1.10–1.83] for low-intensity physical exercise and 1.36 [1.04–1.78] for high-intensity exercise. Doing 1 to 2.5 hours of sport a week is associated with fewer complaints in chronic LBP patients (OR [95% CI]: 0.72 [0.58–0.90]). Hence, there is no formal proof of the harmful effect of leisure physical activities or sports in the LBP patient. It even appears to be the case that maintenance of these activities merely requires adjustment of the technique or intensity; this enables the patient to maintain or achieve physical fitness, which improves health status and reduces risks related to sedentariness .

The present work’s limitations are due (at least in part) to the poor quality of the clinical studies, which prevented us from providing firm recommendations and prompted us to examine theoretical data that must be interpreted with care. Furthermore, we did not address the issue of sport in children and teenagers; this topic deserves a separate assessment, in view of the sometimes radically opposing conclusions drawn. Lastly, there are obvious imprecisions in terms of the definition of the intensity of a physical activity or sport, which is significantly influenced by age and the type of activity. In the absence of relevant assessments, we were unable to specify this aspect further.

1.4

Conclusion

There is no formal proof of a harmful effect of leisure physical activities or sports on LBP.

The resumption of physical activity is the expected outcome of an FRP in LBP but can also follow on from an episode of back pain; it then constitutes a factor that favours the maintenance of benefit and (probably) more rapid recovery. Swimming, walking, cycling and indeed tai chi can be of value, as long these activities (having been initiated during or immediately after an FRP) are carefully monitored in terms of intensity, duration and appropriate technical adjustments. The literature provides some answers in these respects.

In most cases, the resumption of more intense sporting activity is not associated with an abnormally high incidence of LBP (relative to the general population). Even though the biomechanical stresses that are inherent to certain sports can be considered as a risk factor for LBP, changes in technique, regular training and advice from both a therapist and an expert trainer can enable LBP patients to maintain their physique fitness and thus at least avoid complications related to sedentariness.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest concerning this article.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the following people for contributing figures: Patrice Amadieu (a golf coach), Dr Sylvie Courtes-Pellas (a horse rider) and Professor Jacques Pélissier (a cyclist).

2

Version française

Les programmes de restauration fonctionnelle du rachis se sont imposés avec un niveau de preuve suffisant dans la prise en charge du patient lombalgique chronique. Ces programmes incluent :

- •

l’apprentissage d’une gymnastique vertébrale individualisée débouchant sur une auto-rééducation ;

- •

la mise en pratique d’une ergonomie rachidienne adaptée aux situations de vie personnelle et professionnelle ;

- •

l’apprentissage de la gestion d’une poussée douloureuse et enfin le ré-entraînement à l’effort.

Les programmes d’éducation thérapeutique du patient (ETP), qui intègrent de tels programmes, insistent sur l’effet bénéfique d’une activité physique régulière et engagent les patients à cette pratique . La poursuite des exercices est considérée comme bénéfique mais l’adhérence observée dans cette population ne permet de garantir ces bénéfices à long terme .

Les activités physiques ont une influence positive sur la santé (en pratiquant des activités physiques modérées à intenses 3 à 5 fois par semaines) et sur la lombalgie . Il est donc conseillé aux patients lombalgiques de reprendre leurs activités de vie quotidienne, qui sont des activités de faible à moyenne intensité, et qui ont des bénéfices sur la santé lorsqu’elles sont pratiquées régulièrement . Être physiquement actif doit permettre d’améliorer sa forme physique et en conséquence diminuer le risque de lombalgie ou aider à recouvrer ses capacités plus facilement . Cependant, les travaux en charge (soulever ou porter des charges), les activités contraintes en flexion ou en rotation travail sont des facteurs de risque connus de lombalgies et ne peuvent a priori être considérés comme bénéfiques pour les patients lombalgiques chroniques. En revanche, les activités physiques de loisirs, le sport ou les exercices physiques ne sont pas associés au risque de survenue de lombalgie . Certains ont même démontré un effet positif de l’intensité des exercices, du volume d’entraînement ou du type d’exercice (renforcement) sur l’évolution des patients lombalgiques .

La pratique sportive, au sens de la définition du sport de loisir et en compétition n’est pas abordé dans les principales revues concernant l’activité physique et la lombalgie chronique déjà publiées comme dans les recommandations européennes . La revue récente d’Heneweer et al. s’est focalisée sur l’association entre lombalgie et contraintes liées à l’activité physique (travail, rester debout, lever de charge…) . Le sport et l’activité physique de loisir intense (sans précision) ne sont associés qu’à un risque modéré de lombalgie selon les auteurs.

Deux questions sont fréquemment posées aux thérapeutes par le patient lombalgique. Quelle activité physique pratiquer qui leur soit bénéfique ? Peut-on poursuivre la pratique de certains sports sans effet délétère ?

L’objectif de ce travail est de déterminer, à partir d’une revue exhaustive et critique de la littérature, s’il existe des éléments de réponses à apporter au patient lombalgique au décours d’un programme de restauration fonctionnelle sur les bénéfices d’une activité physique de loisir, d’une part, et sur l’absence d’effet délétère lié à la reprise du sport, d’autre part.

2.1

Méthode

Les publications ont été recherchées informatiquement sur les banques de données suivantes : Pubmed, Science Direct, et The Cochrane Library. Les mots clés suivants ont été utilisés : low back pain, lumbar spine, trunk associés avec ( and ) physical activity, sport, soccer, tennis, horseriding, equestrian rider, judo, martial arts, taï chi, tae kwan do, gymnastic, golf, walking, running, jogging, cycling, swimming, handball, basketball. Les langues étaient le français et l’anglais. Tous les articles publiés entre 1990 et décembre 2011 étaient éligibles pour la revue.

La définition de la lombalgie chronique était celle de la Paris Task Force : la lombalgie chronique est une douleur habituelle de la région lombaire évoluant depuis plus de 3 mois. Cette douleur peut s’accompagner d’une irradiation à la fesse, à la crête iliaque, voire à la cuisse et ne dépasse qu’exceptionnellement le genou .

Une distinction sera faite entre activité physique et sport selon les définitions de l’Organisation mondiale de la santé (OMS) reprise par l’Inserm . L’activité physique (AP) est définie par toute situation mettant en jeu la musculature squelettique, quel que soit le but, s’accompagnant d’une augmentation de la dépense énergétique comparativement au repos . Ensuite, les activités physiques et sportives représentent un continuum allant de l’inactivité jusqu’à la pratique d’activités d’intensité élevée de façon régulière (faire des sports de compétition) en passant par des activités modérées (marcher d’un pas vif). Le sport est un sous ensemble de l’AP, spécialisé et organisé, sous forme d’exercice ou compétition, le plus souvent impliquant des organisations (clubs). Nous limiterons cette analyse aux activités physiques de loisir et au sport.

La recherche a été focalisée sur les populations adultes, les activités physiques les plus couramment évoquées au décours de programmes de restauration fonctionnelle du rachis soit la natation, le vélo, la marche, à y ajoutant le taï chi proposé plus fréquemment en Asie du Sud-Est et en Chine, les 6 sports avec le plus de licenciés en 2011 en France : le football et plus généralement les sports collectifs, le tennis, l’équitation, le judo et les arts martiaux, la gymnastique lorsqu’on englobe la gymnastique volontaire, le golf. Les critères de sélection suivants ont été utilisés :

- •

le design de l’étude pouvait être longitudinal prospectif ou rétrospectif, études cas témoins ou observationnelles ;

- •

la population étudiée devait présenter une lombalgie non spécifique depuis plus de 3 mois ;

- •

les critères de mesures devaient au moins comporter une évaluation de la douleur, des répercussions sur la vie personnelle (physiques, fonctionnelles, psychologiques, qualité de vie) ou professionnelle (absentéisme), parfois un indice de performance sportive ;

- •

en l’absence de données dans la population lombalgique, les articles apportant des données biomécaniques et/ou du contrôle moteur liées à la pratique du sport ou de l’activité physique concernée et potentiellement extrapolables à la population lombalgique ont été analysés. De même, les articles établissant un lien entre activités physiques ou sportives et souffrance du rachis lombaire chez les sujets sains sont retenus quand aucune donnée n’est disponible chez les patients lombalgiques. L’objectif est de donner au lecteur quelques éléments de réflexion.

Les références de chaque article ont été analysées en fonction de leur pertinence. Pour chaque article ont été analysés : type d’étude, population, intervention, critères d’évaluation, sélection des participants, qualité méthodologique, pertinence clinique, extraction des données, niveau d’évidence.

L’analyse critique a été réalisée par AD et AR en ne retenant que les études en rapport avec la thématique « lombalgie et sport » de niveau 1 à 4 (grade A à C) selon les recommandations de la Haute Autorité de santé (HAS) ; le grade A (preuve scientifique établie) repose sur des méta-analyses d’essais comparatifs randomisés de forte puissance ; le grade B (présomption scientifique) repose sur des essais comparatifs randomisés de faible puissance, des études comparatives non randomisées ou des études de cohorte ; le grade C (faible niveau de preuve) repose sur des études cas témoins (niveau 3), des études rétrospectives ou des séries de cas (niveau 4). En cas de désaccord, l’arbitrage selon les mêmes critères appartenait à EV.

2.2

Résultats

2.2.1

Description des études analysées

Avec l’ensemble des mots clés, 2583 articles ont été trouvés ; 88 ont été retenues car répondant aux critères de qualité ; la lecture de ces articles et de leur bibliographie a permis la sélection de 85 autres articles. Au total 121 articles sont la matière de cette revue ( Fig. 1 ). Cependant, seulement 13 articles étaient en rapport avec les deux questions posées qui concernaient le sujet lombalgique chronique et sa relation avec l’activité physique voire le sport, les autres traitants de la relation entre traumatisme lombaire au cours d’activité sportive intense, ou pratique sportive de haut niveau et souffrance rachidienne. Les principaux résultats sont présentés dans le Tableau 1 . Les articles qui traitaient des contraintes mécaniques auxquelles le rachis était soumis pour une activité physique ou sportive donnée, des techniques de prévention y compris celles concernant le matériel et le geste sportif on été conservés (42 articles).