This article describes the evolution of vocational rehabilitation and the development of the rehabilitation counselor’s role as the generally accepted expert in forensic vocational rehabilitation assessment. The vocational rehabilitation process is discussed within an empirically derived structural model of forensic vocational assessment. The concept of work-life expectancy is discussed as a key feature in estimating the duration of time vocational damages are likely to occur based on a person’s remaining work participation.

Key points

- •

Private rehabilitation counselors use an established vocational rehabilitation process and work extensively in settings with the potential to be involved in legal proceedings.

- •

The vocational rehabilitation process and evaluation framework have given way to the vocational rehabilitation counselor’s contemporary role as the generally accepted expert in vocational rehabilitation, evaluation, and vocational earning capacity assessment.

- •

To translate medical and functional information into life situation participation inhibitors or facilitators, the vocational rehabilitation counselor must know, understand, and take into account the contextual factors in which the injured person is most likely to exert those capacities.

- •

A person’s ability to participate in the labor market can be complicated by disability-related issues, leading to a person experiencing periods of intermittent or decreased work availability over his or her remaining work life.

- •

Assessing impairment related to vocational functioning within a forensic context involves a complex and systematic review, evaluation, and synthesis of multiple domains of data that consider both the evaluee (labor supply) and the labor market (labor demand).

Introduction

The field of vocational rehabilitation grew out of a disability movement that has been developing and evolving over the past one hundred years. By the turn of the 20th century, the prevailing opinion toward occupational injuries was that “if the dangerous conditions were present when the worker took the job, he could be assumed to have accepted the risk and the possibility of injury [and] could not collect.” (p13) Workers’ compensation laws were not part of the national conversation, as American business leaders feared that such laws would reduce profit margins by increasing business operating costs. Despite these objections, the first compulsory state workers’ compensation law was enacted in New York in 1910. By 1948, every state had adopted some form of workers’ compensation legislation.

Early workers’ compensation laws did not explicitly provide vocational rehabilitation services, but such laws began to make legislators more aware of the need for vocational rehabilitation programs. The first federal-state rehabilitation program (the Barden-LaFollette Act) was passed in 1948 and was intended to provide rehabilitation services to persons who were blind. During World War II, significant medical advances were realized that further advanced the field of rehabilitation, resulting in decreased rates of mortality for combat-related spinal cord injury, amputation, and burns. Twenty years after the end of World War II, approximately 1400 of the 2500 soldiers experiencing combat-related paraplegia were employed. With increased rates of survival came an increased need for long-term medical management of persons with chronic rehabilitative needs, leading to the American Medical Association beginning to view comprehensive rehabilitation management as the third phase of medical care, after the preventive and curative phases. By 1947, the council that would ultimately become the American Board of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation was charted by the American Medical Association.

Between 1954 and 1965, funding for federal-state vocational rehabilitation services quadrupled to over $150 million. The value of these services in 2012 dollars would be more than one billion dollars. With increased federal funding also came increased costs for public-sector vocational rehabilitation efforts. In response, during the early 1970s, the insurance industry began to initiate private rehabilitation efforts aimed at cost containment and proactive rehabilitation initiatives. Changing workers’ compensation laws, greater public awareness of the cost of occupationally injured workers, and the general social attitude toward persons with disabilities helped give rise to a robust private vocational rehabilitation sector in the United States.

From a practical perspective, private-sector and public-sector rehabilitation roles and goals are significantly different. Public-sector vocational rehabilitation efforts are typically more focused on assisting clients achieve maximum vocational potential. Conversely, the primary focus of private-sector vocational rehabilitation typically revolves around returning an individual with a disability or injury to work, or establishing the potential of a person to work, earning compensation similar to what he or she was earning at the time of injury, or in cases of diminished earning capacity, establishing the most probable earning capacity in work for which the individual retains vocational capacity. Private rehabilitation counselors use an established vocational rehabilitation process and work extensively in settings with the potential to be involved in legal proceedings.

Introduction

The field of vocational rehabilitation grew out of a disability movement that has been developing and evolving over the past one hundred years. By the turn of the 20th century, the prevailing opinion toward occupational injuries was that “if the dangerous conditions were present when the worker took the job, he could be assumed to have accepted the risk and the possibility of injury [and] could not collect.” (p13) Workers’ compensation laws were not part of the national conversation, as American business leaders feared that such laws would reduce profit margins by increasing business operating costs. Despite these objections, the first compulsory state workers’ compensation law was enacted in New York in 1910. By 1948, every state had adopted some form of workers’ compensation legislation.

Early workers’ compensation laws did not explicitly provide vocational rehabilitation services, but such laws began to make legislators more aware of the need for vocational rehabilitation programs. The first federal-state rehabilitation program (the Barden-LaFollette Act) was passed in 1948 and was intended to provide rehabilitation services to persons who were blind. During World War II, significant medical advances were realized that further advanced the field of rehabilitation, resulting in decreased rates of mortality for combat-related spinal cord injury, amputation, and burns. Twenty years after the end of World War II, approximately 1400 of the 2500 soldiers experiencing combat-related paraplegia were employed. With increased rates of survival came an increased need for long-term medical management of persons with chronic rehabilitative needs, leading to the American Medical Association beginning to view comprehensive rehabilitation management as the third phase of medical care, after the preventive and curative phases. By 1947, the council that would ultimately become the American Board of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation was charted by the American Medical Association.

Between 1954 and 1965, funding for federal-state vocational rehabilitation services quadrupled to over $150 million. The value of these services in 2012 dollars would be more than one billion dollars. With increased federal funding also came increased costs for public-sector vocational rehabilitation efforts. In response, during the early 1970s, the insurance industry began to initiate private rehabilitation efforts aimed at cost containment and proactive rehabilitation initiatives. Changing workers’ compensation laws, greater public awareness of the cost of occupationally injured workers, and the general social attitude toward persons with disabilities helped give rise to a robust private vocational rehabilitation sector in the United States.

From a practical perspective, private-sector and public-sector rehabilitation roles and goals are significantly different. Public-sector vocational rehabilitation efforts are typically more focused on assisting clients achieve maximum vocational potential. Conversely, the primary focus of private-sector vocational rehabilitation typically revolves around returning an individual with a disability or injury to work, or establishing the potential of a person to work, earning compensation similar to what he or she was earning at the time of injury, or in cases of diminished earning capacity, establishing the most probable earning capacity in work for which the individual retains vocational capacity. Private rehabilitation counselors use an established vocational rehabilitation process and work extensively in settings with the potential to be involved in legal proceedings.

Vocational rehabilitation process

Rubin and Roessler described the vocational rehabilitation process as “a four-phase sequence, beginning with evaluation and moving through planning, treatment, and termination [placement].” (p289) For any given case, the precise services provided by a vocational rehabilitation expert will depend on the context of the referral, funding source, regulatory requirements, and specific referral questions posed to the rehabilitation consultant. A vocational rehabilitation consultant may be involved in any one or all phases of the vocational rehabilitation process. For this article, emphasis is placed on the first 2 phases: evaluation and planning.

Nadolsky described vocational evaluation as a process intended to predict work behavior and vocational potential by applying vocational rehabilitation techniques and procedures. Vocational evaluation is a process that systematically uses real or simulated work as the focal point for assessment and career exploration. In conducting the evaluation, the vocational rehabilitation consultant synthesizes data from all rehabilitation team members that may include medical, psychological, economic, and other data sources such as cultural, social, and vocational information.

Since the genesis of vocational rehabilitation and evaluation, the research literature has contributed substantially to describing the factors and issues relevant to determining a person’s vocational capacity. Assessment of disability related to vocational functioning involves evaluating multiple domains of both endogenous and exogenous variables. Individual, social, economic, and political influences merge to form the unique vocational and human capital profile an individual presents to an employer when being considered for work opportunity. Farnsworth and colleagues wrote that the process of vocational evaluation draws on clinical skills from the fields of psychology, counseling, and education. Specific skills include file review, diagnostic interviewing, psychometric testing, clinical observation, data interpretation, and career counseling. These skills, when used within the vocational rehabilitation process, are important to evaluating a person’s skills, abilities, and capacity to perform work activity for which the person is either qualified or may be able to become qualified. The vocational rehabilitation process and evaluation framework have given way to the vocational rehabilitation counselor’s contemporary role as the generally accepted expert in vocational rehabilitation, evaluation, and vocational earning capacity assessment.

Medical foundation for vocational rehabilitation assessment

The ability of a person to perform the functions expected for occupational participation is predicated on the work capacity of that individual. The loss of a body function, a developmental delay, or an injury or illness may decrease a person’s everyday functioning, including work functioning. Consequently, a medical condition leading to functional limitations or impairment may reduce a person’s earning capacity. The ability to find a job, to sustain employment, or to attain higher levels of performance compared with a person with no impairment may lead to a vocational disability.

An important paradigm shift has occurred in the last 50 years in the construct of disability. Since the mid-20th century, disability was explained through the biomedical model, where a linear relationship was assumed between the severity of a medical condition and the consequent severity of the patient’s disability. The birth and increased popularity of Engel’s biopsychosocial model in the late 1970s led to an important change in the perception and research approach toward disability. Disability is no longer seen solely as a medically related construct, but instead as an intricate melding of a variety of variables. These variables include not only the person’s health condition but also the individual’s activity restrictions, life situation participation, and contextual influences as inhibitors or facilitators of disability. The International Classification of Functioning (ICF) framework was adopted in 2001 by resolution of the World Health Organization to explain and operationalize the interaction of health domains. The ICF considers functioning and disability as the 2 extremes in a continuum of health. A person’s body functions and structures, previously seen in the biomedical model as the primary—if not unique—cause of disability, are now interacting with a person’s activity participation or restrictions (the individual’s level of capacity), as well as actual execution of those activities in his or her usual environment (the individual’s level of performance). In this framework, disability is multidimensional. The medical condition is no longer the primary determinant of the disability’s severity. The World Health Organization has operationally defined many of the key concepts for understanding the various constructs within the ICF paradigm :

Body functions are physiologic functions of body systems, including psychological functions.

Body structures are anatomic parts of the body, such as organs, limbs, and their components.

Impairments are problems in body function or structure, such as a significant deviation or loss.

Activity is the execution of a task or action by an individual.

Participation is involvement in a life situation.

Activity limitations are difficulties an individual may have in executing activities.

Participation restrictions are problems an individual may experience in life situations.

Environmental factors comprise the physical, social, and attitudinal environment in which people live and conduct their lives.

In many countries, for legal and regulatory purposes, a causal relationship still needs to be generated to attribute responsibility for pecuniary damages, indemnity, and health-related service payments, despite the knowledge that, even though a medical condition may have healed or not been diagnosed, the residual disability may linger because of other factors. As it is, medical and functional evidence constitute the necessary foundation to accept disability as a real entity. Therefore, a relationship must be established between the medical condition, the functional restrictions (ie, ICF’s activity limitations), and the person’s work disability (ie, ICF’s participation restrictions).

Medical evidence is gathered by consulting with medical providers. Medical doctors are called on to establish disturbances in body structures and functions and to propose appropriate treatments to restore the body’s premorbid health. Because of this knowledge and the lingering biomedical model still in effect in many policies and regulations regarding disability eligibility, medical doctors are often required or are expected to opine on work disability despite their lack of training, knowledge, and experience in diagnosing or treating disability as the ICF defines it. Physicians specialized in disability rating are likely to rely on functional information to complement their medical findings and to define vocational readiness when such information is provided to them. Such information often comes from a functional capacity evaluation that is most typically (but not always) completed by an occupational or physical therapist. For mental health disorders, psychiatrists, psychologists, and other licensed mental health professionals may provide diagnostic and treatment-related opinions. For people with brain diseases or injury, a neuropsychologist may determine the foci of structural and functional limitations.

This affects the forensic rehabilitation consultant in establishing the work-life participation and readiness. Under the ICF framework, the forensic vocational rehabilitation consultant is not able to extract life participation (“disability”) information through simple activity restrictions provided by medical evidence because too many variables are missing. Medical and psychological evaluation findings are the result of a standardized or protocol-oriented approach that focuses on body structure and functions with a slight overlap on activity restrictions in a constrained environment. The ICF, as discussed earlier, defines this as capacity. However, work participation relates to performance within in a given context—where the environment changes, so too may performance, indicating that performance is seen as a separate entity from capacity, albeit most likely related, involving actual activity execution within a given environment.

To translate medical and functional information into life situation participation inhibitors or facilitators, the vocational rehabilitation consultant must know, understand, and take into account the contextual factors in which the person is most likely to exert those capacities. This complicates the picture, as the vocational rehabilitation consultant rarely has access to a potential environment in which the person could execute their capacities. However, knowing this margin of error helps the forensic vocational consultant present an opinion using a comfortable confidence interval, acknowledging those unobservable or untestable factors in the analysis and opinion formation. Through this personal and professional knowledge of the labor market, job demands, cultural and organizational demands of specific industries, and the current labor market, the vocational rehabilitation consultant may identify those missing criteria, exposing not only the gap in the predictive ability of the available determinants, but also explaining it. Only then can accurate work disability or readiness be established.

Vocational and rehabilitation assessment

The opinions expressed by forensic vocational rehabilitation experts are typically presented as evidence in a legal venue and, as such, are subject to legal scrutiny under the rules of evidence for the venue in which the matter is being heard. The model for many rules of evidence is the Federal Rules of Evidence. With respect to expert witness testimony, the Federal Rules of Evidence, Rule 702 reads:

If scientific, technical, or other specialized knowledge will assist the trier of fact to understand the evidence or to determine a fact in issue, a witness qualified as an expert by knowledge, skill, experience, training, or education, may testify thereto in the form of an opinion or otherwise, if (1) the testimony is based upon sufficient facts or data, (2) the testimony is the product of reliable principles and methods, and (3) the witness has applied the principles and methods reliably to the facts of the case.

Reliability of expert methods is of paramount importance if deference is to be given to an expert’s opinions. According to Field and Choppa, Rule 702 is important to vocational rehabilitation experts because it provides a basis for the admission of expert testimony on the grounds that vocational rehabilitation consultants possess unique knowledge, skill, experience, and training. Despite this, the vocational consultant must still demonstrate reliable application of methods and protocols in reaching conclusions. Barros-Bailey and Neulicht proposed using both qualitative and quantitative data sources to describe how various factors interact and influence an individual’s vocational characteristics. They referred to this hybrid method of integrating qualitative and quantitative data in rehabilitation case conceptualization as “opinion validity.” (p34) Moving from a purely quantitative approach to one that combines both quantitative and qualitative data analysis requires applying expert clinical judgment that is generally learned through one’s training, skills, and experience. Choppa and colleagues wrote about the need for one’s clinical judgment to be predicated on an evidence-based scientific foundation as is practical. These authors described a model to apply clinical judgment that “incorporates such activities as direct observation, diagnosis (vocational evaluation and assessment), dispassionate (objective) and analytical observations, discerning and comparing (evaluating and synthesizing varieties of information), to assert a proposition (opinion) about the client.” (p135) The processes described by Barros-Bailey and Neulicht and Choppa and colleagues both illustrate the importance of integrating data from multiple sources to arrive at rehabilitation conclusions that are valid and reliable and would stand the test of legal scrutiny.

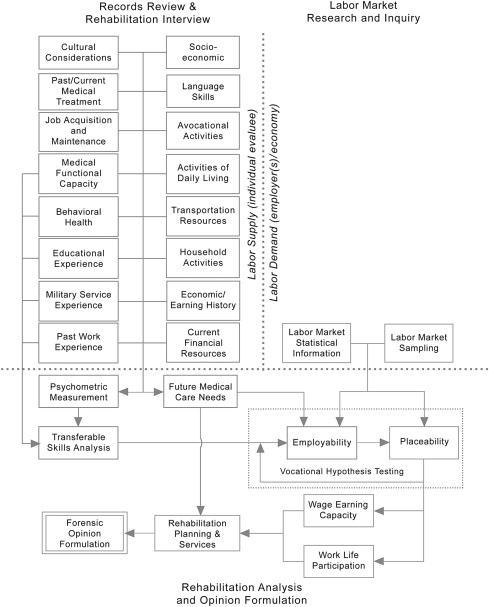

The Vocational and Rehabilitation Assessment Model (VRAM) ( Fig. 1 ) is an empirically derived structural model of vocational and rehabilitation assessment specifically for use in forensic settings. The structured presentation of VRAM is useful for visualizing the relationship and interaction of construct domains within the model. The model is divided into 3 distinct operational facets:

- •

Records review and rehabilitation interview (labor supply);

- •

Labor market research and inquiry (labor demand); and

- •

Rehabilitation analysis and opinion formulation, which represent the integration of the labor supply and labor demand aspects of the evaluation equation.

The balance of this article discusses each VRAM section and the data considered in each section.

Records review and rehabilitation interview

The records review and rehabilitation interview are, in most cases, requisite first steps in conducting a vocational and/or rehabilitation assessment. Conceptually, at this step in the assessment process, the rehabilitation consultant is focused on identifying the multitude of evaluee-specific variables expected to inhibit or facilitate present and future vocational and rehabilitation potential. Records review involves an analytical review of existing evidence with particular attention directed toward issues affecting vocational potential. Records review coupled with clinical interview findings are central to formulating a working hypothesis for further case-specific research, analysis, and vocational hypothesis testing. Table 1 describes 16 core domains of data identified in a 2011 Delphi study. These domains are considered essential elements in conducting a thorough vocational rehabilitation analysis. Not every data domain will necessarily apply in each case. However, to render the most accurate opinions possible, the vocational rehabilitation consultant has a responsibility to examine every element that may serve to influence the evaluee’s vocational potential. Domains found not to be applicable after examination are simply left out of the equation, having gained the confidence that their exclusion will not influence the final analysis.