Vocal Cord Paralysis after Anterior Cervical Spine Surgery

Daniel R. Fassett

Ronald I. Apfelbaum

OVERVIEW

Vocal cord dysfunction is one of the most common complications associated with the anterior surgical approach to the cervical spine. In anterior cervical spine surgery, vocal cord dysfunction may arise from laryngeal edema or scarring, recurrent laryngeal nerve injury, or superior laryngeal nerve injury. In the majority of cases, a hoarse voice after surgery is due to laryngeal edema caused by endotracheal (ET) tube and soft tissue manipulation and will improve over a few days. Vocal cord paralysis, which is caused by recurrent laryngeal nerve injury, is less common but more severe in terms of the potential impact on a patient’s quality of life. Symptoms of vocal cord paralysis can include hoarse voice, vocal fatigue, postdeglutition cough, choking, and aspiration.

Several techniques can be used to minimize the risk of vocal cord dysfunction after anterior cervical surgery, but this complication still occurs in a small percentage of patients. In certain patients, such as singers or public speakers, dysphonia from vocal cord dysfunction is a devastating complication and, therefore, consideration should be given to alternative approaches. This chapter will review the incidence of this complication, relevant anatomy, techniques to minimize the risk of dysphonia, and the management of patients with vocal cord dysfunction after anterior cervical surgery.

INCIDENCE OF COMPLICATION

Hoarseness after anterior cervical surgery is a common finding, with as many as 51% of patients reporting a hoarse voice postoperatively (1,2,3). In the vast majority of cases, the voice changes are simply from laryngeal edema caused by endotracheal intubation and soft tissue manipulation during surgery (1,4). The incidence of recurrent laryngeal nerve injury is reported between 0.07% and 11% in anterior cervical spine surgery series (1,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21).

Because of the apparent discrepancy in the incidence rates between reviews of surgeons’ records and patient surveys, it is important to consider the type of review and source of the data used in the review. Most series are retrospective reviews based on the surgeons’ records and hospital notes. In these series, the reported incident rates of dysphonia and other complications are lower than those in series that have used patient questionnaires. Edwards et al. (22) compared the incidence of dysphonia after anterior cervical spine surgery as reported by surgeons in their medical records with the results from a patient survey from the same population. They found that patients reported dysphonia seven times more frequently than the surgeons’ records indicated.

Other factors such as age, gender (2), level of surgery (20), number of levels operated (20), duration of surgery (2), and fusion procedures (18) are also speculated to impact

the risk of vocal cord dysfunction after anterior cervical surgery. Beutler et al. (13) and Apfelbaum et al. (20) both found an increased incidence of recurrent laryngeal nerve injury associated with reoperative anterior cervical fusions (9.5% and 10% in reoperative cases compared with 2.7% and 3.3% in virgin cases).

the risk of vocal cord dysfunction after anterior cervical surgery. Beutler et al. (13) and Apfelbaum et al. (20) both found an increased incidence of recurrent laryngeal nerve injury associated with reoperative anterior cervical fusions (9.5% and 10% in reoperative cases compared with 2.7% and 3.3% in virgin cases).

RELEVANT ANATOMY

Surgical Approach

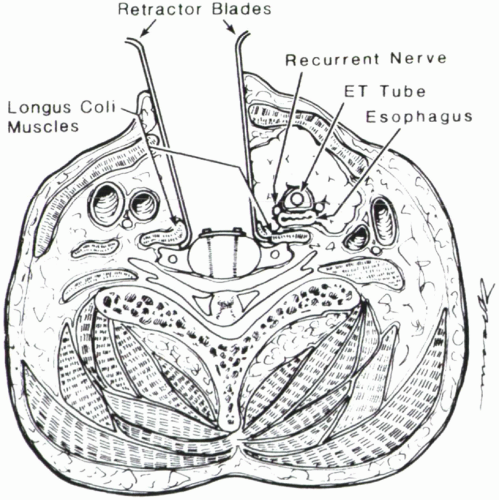

The anterior cervical approach is one of the most common approaches used in spine surgery. In this approach, the platysma is divided, and a dissection plane is carried down along the medial border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle to the anterior cervical spine. The contents of the carotid sheath (carotid artery, jugular vein, and vagus nerve) are retracted laterally, and the strap muscles, trachea, recurrent laryngeal nerve, and esophagus are retracted medially (Fig. 4.1).

Recurrent Laryngeal Nerve (Inferior Laryngeal Nerve)

The recurrent laryngeal nerve supplies all of the muscles of the larynx except for the cricothyroid muscle, which is supplied by the superior laryngeal nerve. In addition to supplying motor fibers to the laryngeal muscles, the recurrent laryngeal nerve also supplies sensation to the larynx below the level of the vocal folds (23).

The complex anatomic path of the recurrent laryngeal nerves is secondary to the embryological development of the branchial arches. The recurrent laryngeal nerves arise from the vagus nerve in close proximity to the sixth branchial arch. On the right side, the fifth and sixth branchial arches involute and the recurrent laryngeal nerve thus lies beneath the fourth branchial arch vessel, which becomes the right subclavian artery. On the left side, the sixth branchial arch persists as the ductus arteriosus and thus prevents the left recurrent laryngeal nerve from migrating upward. As the heart and thoracic organs descend into the thoracic cavity, the laryngeal nerves assume their recurrent course. On the right side, the recurrent laryngeal nerve passes beneath the right subclavian artery and then ascends medially along the lateral surfaces of the trachea and esophagus. On the left side, the recurrent laryngeal nerve passes beneath the aorta at the level of the ligamentum arteriosum (remnant of ductus arteriosus) before ascending to the laryngeal structures (13,17,24,25).

The left recurrent laryngeal nerve has a more vertical and predictable course in comparison with the right recurrent laryngeal nerve. The left recurrent laryngeal nerve usually lies in the tracheoesophageal groove throughout most of its ascent. On the right side, the recurrent laryngeal nerve takes a more oblique course in its initial ascent and it often lies outside of the tracheoesophageal groove during a large portion of its ascent. The combination of a more oblique ascent, less redundancy (shorter nerve), and a path outside of the tracheoesophageal groove leaves the right recurrent laryngeal nerve more exposed. Thus, it has been theorized, it may be more vulnerable to retraction and compression injury (9,19,26,27,28,29,30).

A variant called the nonrecurrent laryngeal nerve has been associated with increased risk of vocal cord paralysis in anterior neck surgery. This nonrecurrent laryngeal nerve arises from the vagus nerve and passes directly to the laryngeal structures at approximately the level of or just below the cricoid cartilage (23,27,31). With its short course and abrupt angle of origin from the vagus, a nonrecurrent laryngeal nerve is prone to stretch injury by the placement of the retractors used in anterior cervical spine surgery. This aberrant variant is also at greater risk for transection with anterior cervical surgery as it may cross the operative field in the traditional dissection plane and be cut inadvertently. When present, nonrecurrent laryngeal nerves are almost always found on the right side, which is one reason that some surgeons advocate a left-sided approach to the cervical spine. The incidence of nonrecurrent laryngeal nerves on the right side is reported between 0.3% and 2.4%, and nonrecurrent laryngeal nerves on the left side are significantly less common.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree