Multiple sclerosis has several ophthalmic manifestations, including optic neuritis, internuclear ophthalmoplegia, and nystagmus. The presentation, treatment, and prognosis of visual complaints secondary to multiple sclerosis are discussed. Additionally, the use of optical coherence tomography and complications related to the use of fingolimod are considered.

Key points

- •

A majority of patients with multiple sclerosis have an ophthalmic manifestation over the course of their disease.

- •

Optic neuritis is the most common ophthalmic manifestation of multiple sclerosis and, although typically there is spontaneous visual recovery, it is often treated with intravenous (IV) steroids.

- •

Patients treated with fingolimod need to be followed with serial eye examinations due to the risk of developing macular edema.

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) has several manifestations that can affect vision, with a majority of patients having a visual complaint over the course of their disease. The most common ophthalmic manifestations of MS are listed in Box 1 and discussed later. In addition, ocular complications of treatment are considered.

Optic neuritis

Internuclear ophthalmoplegia

Nystagmus

Skew deviation

Cranial nerve 3, 4, or 6 palsies

Retrochiasmal visual pathway demyelination

Intermediate uveitis

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) has several manifestations that can affect vision, with a majority of patients having a visual complaint over the course of their disease. The most common ophthalmic manifestations of MS are listed in Box 1 and discussed later. In addition, ocular complications of treatment are considered.

Optic neuritis

Internuclear ophthalmoplegia

Nystagmus

Skew deviation

Cranial nerve 3, 4, or 6 palsies

Retrochiasmal visual pathway demyelination

Intermediate uveitis

Optic neuritis

Optic neuritis is the most common ophthalmic manifestation of MS, with an incidence of up to 20% of patients having optic neuritis as the initial clinical presentation of MS and up to 50% of patients having at least 1 episode over the course of their disease.

Symptoms

Optic neuritis typically presents with acute loss of vision in 1 eye over a period of days. The vision loss is often preceded by or occurs concurrently with periorbital pain worsened with extraocular movements. The pain associated with optic neuritis is likely secondary to traction on the inflamed nerve sheath by the extraocular muscles at the orbital apex and tends to improve after several days. Vision loss typically progresses over several days and then gradually improves over weeks to months.

The vision loss in optic neuritis can vary widely, with acuities ranging from 20/20 to no light perception. Visual field defects should be present in optic neuritis but can range from small scotomata to arcuate or altitudinal defects to diffuse loss. Contrast sensitivity is typically reduced and patients often report changes in color vision.

Examination Findings

On examination, a relative afferent pupillary defect should be seen in most cases. An afferent pupillary defect may not be seen if a patient has had a prior episode of optic neuritis or other optic neuropathy in the contralateral eye or has bilateral simultaneous and symmetric onset. Otherwise, the possibility of other causes of vision loss must be considered. On funduscopic examination, the optic nerve appears completely normal in approximately 65% of patients, with the remaining presenting with optic disc edema. The presence of optic disc hemorrhages, high-grade disc edema, vitreous cell, or a macular star is not consistent with the diagnosis of demyelinating optic neuritis and should prompt a work-up for other causes of optic neuropathy.

Ancillary Tests

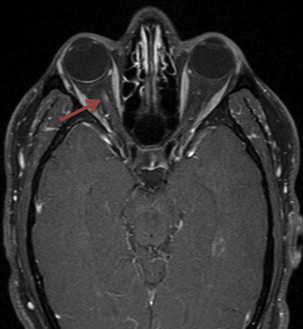

Orbital MRI may be helpful in the diagnosis of optic neuritis in some cases. On gadolinium-enhanced, fat-suppressed T1 images, swelling and enhancement of the optic nerve may be seen approximately 90% of the time. Because optic neuritis is a clinical diagnosis, the absence of enhancement does not rule out the diagnosis of optic neuritis, and additionally the presence of enhancement is not specific for demyelinating optic neuritis. Fig. 1 shows an example of optic nerve enhancement on MRI in the setting of an acute episode of optic neuritis. Usually orbital imaging is reserved for atypical cases; however, as discussed later, brain MRI is an important prognostic test to assess the risk of future MS.

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) can be a useful adjunctive tool in the monitoring of optic nerve health in the setting of demyelinating optic neuritis. OCT, an optical form of ultrasound imaging, can provide high-definition cross-sectional, and 3-D imaging of the retina and optic nerve head. At initial presentation in optic neuritis, the retinal nerve fiber layer (rNFL) thickness is typically normal to slightly swollen. As visual recovery occurs, the rNFL may progressively thin, often preferentially in the temporal quadrant of the optic nerve head over a period of 6 months ( Fig. 2 ). Loss of rNFL thickness can correlate with other subjective measures of visual dysfunction, such as low-contrast acuity. OCT is thought to be a useful potential adjuvant biomarker of disease activity in MS by noninvasively documenting axonal loss at the optic nerve head through serial rNFL measurements in patients.

Differential Diagnosis

Depending on a patient’s presentation, other causes must be considered. Pain with extraocular movements can be seen with posterior scleritis and orbital myositis. Mildly decreased vision, dyschromatopsia, and an absence of disc edema can be seen in central serous retinopathy. Optic neuropathies associated with disc edema include acute anterior ischemic optic neuropathy, neuroretinitis, and other inflammatory or infectious causes of optic neuritis. Vision loss that is bilaterally sequential and persists without improvement can be concerning for Leber hereditary optic neuropathy, a mitochondrially inherited disease that typically manifests in men in their teens to 20s. Bilateral simultaneous onset, especially when associated with longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis, should prompt further evaluation for neuromyelitis optica (NMO).

Treatment and Prognosis

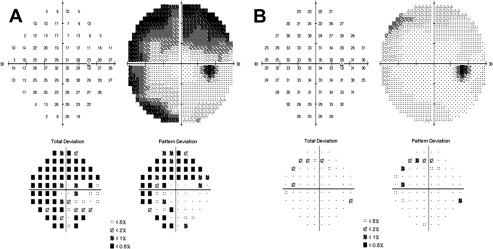

The landmark Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial (ONTT) generated significant information regarding the natural history of demyelinating optic neuritis by evaluating the role of steroids in the treatment of optic neuritis and the association of optic neuritis and MS. Patients with a diagnosis of optic neuritis were randomized to receive placebo, oral prednisone, or IV methylprednisolone followed by an oral prednisone taper. Without any intervention, the vision loss secondary to optic neuritis typically spontaneously improves over the course of weeks to months, with approximately 95% of patients achieving 20/40 or better visual acuity and only 3% of patients with vision loss of 20/200 or worse. More severe loss of vision at presentation is associated with worse visual outcome. One year after an attack in optic neuritis, there was no significant difference in visual acuity, contrast sensitivity, color vision, or visual field defects between the treatment arms. The administration of IV steroids, however, was well tolerated and shown to speed recovery of vision loss. Oral prednisone alone failed to improve vision and was associated with increased risk of new attacks of optic neuritis in the first 2 years (30% vs 16% in placebo and 14% in IV steroid group) and, therefore, is contraindicated in the treatment of optic neuritis. Additionally, IV steroids were shown to reduce the risk of developing MS in the first 2 years (7.5% risk vs 16.5% risk in placebo). The decision on whether to give IV steroids is based on the severity of vision loss, risk of developing MS, associated comorbid conditions, and patient preference. Fig. 3 shows a Humphrey visual field of a patient at presentation of acute optic neuritis in the right eye and then 5 weeks after administration of IV solumedrol.

Although most patients have significant visual recovery, residual deficits are often apparent. In the 15-year follow-up of the ONTT, 72% of affected eyes had acuities of 20/20 or better and only 2% of patients had acuities of less than or equal to 20/40 in both eyes. Contrast sensitivity was not different between affected and fellow eyes but was worse in patients who went on to develop MS. Scores on the National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire indicate patients with a history of optic neuritis perceive their visual function to be poorer than those who have not suffered an attack, particularly in those with reduced acuity or neurologic disability secondary to MS.

Association with Multiple Sclerosis

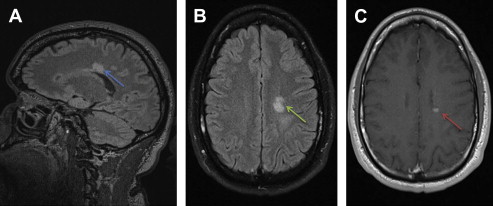

There is a strong association between demyelinating optic neuritis and the diagnosis of MS. From the results of the ONTT, the risk of MS in the setting of optic neuritis is now well established. The overall probability of developing MS after an attack of optic neuritis is 50% in 15 years. This can be stratified further, however, depending on lesion burden on baseline non–contrast-enhanced brain MRI. If a patient has a negative brain MRI at the time of diagnosis of optic neuritis, the risk of developing MS in the following 15 years is reduced to 25%. If 1 or more lesions are present on brain MRI, however, the risk increases to 72%. This information can be useful in counseling patients regarding their prognosis and need for serial monitoring. Fig. 4 shows the brain MRI of the patient described in Fig. 1 .

Long-term Therapy

Given the findings of the ONTT and the known risk of developing MS in the setting of optic neuritis, the Controlled High Risk Avonex Multiple Sclerosis Prevention Study (CHAMPS) evaluated the role of early disease-modifying therapy in reducing the rate of conversion to clinically definite MS. Patients with optic neuritis or other acute demyelinating event and evidence of subclinical demyelination on brain MRI were given IV corticosteroids and randomized to receive placebo or weekly intramuscular injections of interferon beta-1a (Avonex) and followed for 3 years. Interferon beta-1a was shown to reduce the development of clinically definite MS and the development of new brain lesions on MRI.

Similar to the CHAMPS study, the Early Treatment of Multiple Sclerosis (ETOMS) study showed a benefit from early interferon beta-1a treatment. Patients were randomized to weekly interferon beta-1a (Rebif) or placebo after a first episode of demyelinating disease. Treated patients had a lower risk of developing MS in the first 2 years (34% vs 45% for placebo), a lower annual relapse rate (0.33 vs 0.43 for placebo), and a lower disease burden on MRI. Therefore, there is strong evidence of benefit for early treatment with disease-modifying therapies after an episode of optic neuritis in a high-risk population, defined by 2 or more lesions on brain MRI. Table 1 summarizes the 3 landmark trials (discussed previously).

| Trial | Medication | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| ONTT | Methylprednisolone | Faster recovery of visual function. Reduced rate of developing MS in first 2 y |

| CHAMPS | Interferon beta-1a | Reduced rate of developing MS in first 3 y Fewer new or enhancing lesions on MRI |

| ETOMS | Interferon beta-1a | Reduced rate of developing MS in first 2 y Fewer lesions on MRI Decreased annual relapse rate |

Subclinical Optic Neuritis

Some patients who never report symptoms consistent with an acute episode of optic neuritis may have findings on examination consistent with optic neuropathy, decreased acuity, reduced contrast sensitivity, dyschromatopsia, visual field defects, and optic atrophy. rNFL atrophy on OCT can be seen in eyes of patients without prior episodes of optic neuritis and has been shown to correlate with lesion burden on brain MRI. Serial monitoring of rNFL thickness on OCT in MS patients may be beneficial; however, further study in the area is needed.

Neuromyelitis optica

NMO is an inflammatory autoimmune disease that preferentially attacks the optic nerves and spinal cord. Diagnostic criteria include a clinical history of both optic neuritis and transverse myelitis and at least 2 of 3 of the following supportive criteria: brain MRI not diagnostic of MS, spinal MRI with greater than or equal to 3 segment contiguous lesion, and aquaporin 4-IgG seropositivity. The optic neuritis associated with NMO is often bilateral in onset, with more severe vision loss (<20/200) and more severe visual field depression. Bilateral simultaneous optic neuritis, posterior optic nerve or chiasmal involvement, and poor visual recovery should prompt an evaluation for possible NMO. It is important to make the diagnosis of NMO early on because the prognosis for recovery is not as likely compared with optic neuritis in MS. In addition, the use of certain disease-modifying agents, such as beta interferons, natalizumab (Tysabri), and fingolimod (Gilenya), may actually worsen disease activity in NMO.

Other afferent visual pathway lesions

Chiasmal or retrochiasmal demyelination leading to bilateral visual field defects is less common in MS. In the ONTT, 5.1% of patients were found to have bitemporal visual field defects, consistent with chiasmal lesions, and 8.9% had homonymous hemianopias, seen in retrochiasmal disease. The presence of chiasmal involvement in acute optic neuritis should prompt an investigation into possible NMO (discussed previously). Retrochiasmal lesions may occur anywhere along the posterior visual pathway, from the optic tracts to the optic radiations, with large lesions required to create significant visual field defects. Patients with large homonymous or bitemporal visual field defects need to be counseled on whether they are safe to drive, the requirements for which vary by state. Additionally, homonymous hemianopias may make it difficult for a patient to read. Holding a straight edge along the line of text may be helpful. Some patients benefit from turning the text 90° vertically, with a left homonymous hemianopic patient reading up and a right homonymous hemianopic patient reading down, thereby always keeping the next line of text in the preserved visual field. Occasionally prism glasses are used to shift the visual field toward the affected side.

Nystagmus

Nystagmus is a frequent finding in MS, observed in approximately 30% of patients. Several different forms of nystagmus can be seen (listed in Box 2 ). Nystagmus may be asymptomatic or cause oscillopsia, which can be variably bothersome depending on eye position.