Abstract

Objectives

Validate the use of the PPLP scoring scale in the follow-up of athletes after anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction.

Patient and method

We conducted a prospective follow-up study on athletes with ACL reconstruction during several time periods between 2003 and 2009, we analyzed the score validity, its reproducibility, its responsiveness to change and its relevance in the follow-up and monitoring of ACL reconstructive surgeries.

Results

The PPLP scoring scale was defined for the monitoring of ACL reconstruction in athletes. The PPLP tool is made of two parts: the first one (PPLP1) with a total of 100 points for postoperative follow-up and the second one also with a total of 100 points (PPLP2) adding up to the first score for determining a final post-op monitoring score of 200 points. The PPLP2 scoring scale is administered at a distance from the initial ACL reconstruction. For construct validity, we showed the differences in items’ characteristics (coefficient r of 0.20 in 763 patients), and adequate correlation of the PPLP score to other scoring scales found in the literature (OAK, Lysholm, Tegner, Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score [KOOS], Arpege, IKDC Subjective Knee Evaluation Form and Psychovitality Test). The intra/interexaminer reproducibility is excellent going from 0.92 to 1. The PPLP scoring scale shows a statistically significant responsiveness to change during the hospital stay, according to the postoperative delay but with great variations. Complicated clinical evolutions (among 3296 ACL reconstructions with postoperative follow-up) are well identified by a low PPLP score, mainly for complex regional pain syndrome Type 1 (CRPS1: 1.9%) with a mean PPLP1 score of 80.33 whereas uncomplicated clinical evolutions (80.8%) have a mean score of 94.28 with a significant difference ( p < 0.0001). PPL2 scoring scale is significantly correlated to the possibility of getting back to competition ( p = 0.012) and a high score is linked to a faster return to competition (follow-up of 258 patients). The optimal threshold score is 176, and not 170/200, as previously suggested. However, this score remains poorly discriminating in regards to sensitivity (79.7%), specificity (49.3%) and the percentage of athletes returning to competition 2.5 months after completing the PPL2 scoring tool (37.9%).

Conclusion

The PPLP scoring scale was validated in the French language in terms of construct validity, reproducibility and sensitivity. This scoring scale is used for the follow-up and monitoring of ACL reconstruction in athletes, providing useful information on the quality of their recovery particularly during the postoperative phase and the possibilities of getting back to competition.

Résumé

Objectifs

Valider l’utilisation du score PPLP dans le suivi des ligamentoplasties du ligament croisé antérieur (LCA).

Patient et méthode

Nous avons réalisé un suivi prospectif de reconstructions chirurgicales du LCA sur plusieurs phases entre 2003 et 2009, où nous avons analysé la validité du score, sa reproductibilité, sa sensibilité au changement et sa pertinence dans le suivi des ligamentoplasties.

Résultats

Le score PPLP a été précisé pour le suivi des ligamentoplasties chez le sportif. La grille est composée de deux parties : l’une (PPLP1) sur 100 points pour un suivi postopératoire et l’autre également sur 100 points (PPLP2) qui s’additionne au premier score pour un suivi à distance de la chirurgie déterminant un nouveau score de 200 points. Nous avons montré pour la validité de construit le caractère différencié des items (coefficient r de 0,20 chez 763 patients) et la corrélation du score PPLP avec d’autres scores de la littérature (OAK, Lysholm, Tegner, Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score [KOOS], Arpège, IKDC Subjective Knee Evaluation Form subjectif et Psychovitality Test ). La reproductibilité intra-examinateur et extra-examinateur est excellente, allant de 0,92 à 1. Le score PPLP évolue de façon statistiquement significative au cours de l’hospitalisation et en fonction du délai opératoire avec des phases de plus grandes variations. Les évolutions cliniques compliquées (parmi 3296 ligamentoplasties suivies en postopératoire) sont bien matérialisées par un score PPLP faible, notamment les neuro-algodystrophies (syndrome douloureux régional complexe de type 1 [SDRC1] : 1,9 %) avec un PPLP1 moyen de 80,33 alors que les évolutions sans complications (80,8 %) ont un score moyen de 94,28 avec une différence significative ( p < 0,0001). Le score PPLP2 est corrélé à la possibilité de reprendre la compétition de façon significative ( p = 0,012) et un score élevé est lié à une reprise plus rapide (suivi de 258 patients). Le score barrière optimal est de 176 et non de 170/200, comme il l’avait été proposé auparavant. Cependant, ce score de 176 reste peu discriminant au vue de la sensibilité (79,7 %), de la spécificité (49,3 %) et du pourcentage de reprise de la compétition à 2,5 mois de la réalisation du score (37,9 %).

Conclusion

Le score PPLP a été validé en termes de construction, de reproductibilité et de sensibilité en langue française. C’est un score de suivi de la ligamentoplastie du LCA, qui permet de donner des indications sur la qualité de la récupération, notamment en postopératoire, et sur les possibilités de reprise de la compétition.

1

English version

1.1

Introduction

There are several tools used for the follow-up of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction surgery , yet very few of them were assessed with an adequate and complete methodology . Most times, authors limit their analysis to only one validity parameter, resulting in several different studies that are difficult to compare for determining if one scoring tool is better than the other . Furthermore, even though isokinetic assessments are frequently included as part of the clinical monitoring of ligament reconstructive surgeries , they were never before integrated as part of a follow-up scoring scale. The PPLP score has rarely been described in the literature , and had not been validated to this day. This scoring scale is used for a proper monitoring and follow-up of ACL reconstruction in athletes and can evaluate their chances of getting back to competition ( Appendix A ). It is based on subjective, clinical and functional data as well as a complete evaluation of the patients’ muscular strength. This tool is made of two parts: the first one (PPLP1) for a postoperative follow-up and the second one (PPLP2) adding up to the first score for a long-term follow-up (several weeks after the initial surgery), thus making up a new score. Our objective was to evaluate its reproducibility, its validity, its responsiveness to change and its relevance in the follow-up of ACL reconstruction surgeries.

1.2

Material and method

1.2.1

PPLP scoring scale

PPLP1 grid ( Appendix A ) is defined by subjective parameters (pain, apprehension and patient’s sensations) associated to clinical examination parameters (patella perimeter, joint laxity tests, joint range of movement, pain in the graft area, and amyotrophy). It also takes into account simple functional parameters such as walking with or without technical aids (canes, braces), and also the various medications taken by the patient. PPLP1 allows the monitoring of ACL reconstruction patients during the postoperative period, with a possible maximal score of 100 points.

PPLP2 ( Appendix A ) is defined by a functional assessment (running, cardiovascular training on a bike) and an isokinetic evaluation. This score adds up to the PPLP1 score to make up a new score with a maximum of 200 points. The postoperative delay is defined by the time period between the initial surgery and the test completion. Isokinetic tests are done on the quadriceps and hamstrings in a concentric mode at 90°/s (repeated six times) and 240°/s (repeated 15 times), then in an eccentric mode at 90°/s (repeated six times) on a Biodex-type isokinetic equipment, after an initial warm-up session that includes cycling, leg-press and hamstring training for about 15 minutes completed by two to three warm-up movements on the isokinetic equipment. The patient sits down on the equipment, with a dynamic knee range of motion (ROM) going from 0 to 90°. The arms are positioned on the lateral handles. One highly competent examiner performed the entire test. The test’s total duration varies from 30 to 40 minutes. Quantifying the peak torque (PT) between the operated side and the healthy side permits the calculation of the PPLP2 score.

1.2.2

Method

Our study was conducted in several prospective stages between 2003 and 2009, in order to encompass the various parameters needed to validate this scoring scale. The numerous validation criteria and measurement methods (clinical follow-up and monitoring, questionnaire) required several distinct studies according to the validation requirements of each criterion.

Short follow-up periods on small populations enabled us to compare the PPLP scoring scales with other rating tools found in the literature and we were able to analyze its reproducibility and responsiveness to change during the patients’ hospital stay. Long monitoring periods on large populations were required to observe small statistical changes, such as responsiveness to change according to the postoperative delay (time period between the initial surgery and the completion of the scoring tool), correlation to complications and getting back to competition. Furthermore, depending on the PPLP part that needed to be validated, we differentiated two types of population: the first one included patients during their postoperative phase for the PPLP1; and the other one, for the PPLP2, where patients who had their surgery at a distance from completing the scoring scale. We correlated the PPLP scoring scale to the those scoring tools most commonly found in the literature according to the postoperative delay: PPLP1 was compared to the following scoring scales: OAK knee evaluation, Lysholm rating score and the Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) and PPLP2 was compared to Tegner activity scale, Arpege and the Psychovitality test. Furthermore, we analyzed the complications with PPLP1, since the immediate postoperative delay is the most relevant time period to observe potential clinical complications without any patient recruitment biases. Finally, in the phase of getting back to competition, we only correlated the PPLP2 scoring scale since it was only relevant for patients who had their initial surgery at a distance from completing the scoring scale.

The inclusion criterion was ACL reconstruction in athletes who were involved in regional (minimum), national or international competitions. All surgical techniques for ACL reconstructions were included. The exclusion criteria were complex surgeries, such as an associated posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction, osteotomy or multiple traumas. Some complications were also excluded such as deep bacterial infections or knee instability since they required additional emergency surgery and in regards to the context the PPLP scoring scale was not administered.

The statistical analyses were computed by a statistics specialist with the Statistical Analysis System (SAS) software version 9.1. The threshold p value for statistical significance in hypothesis testing was set at p < 0.05.

1.2.3

The various parameters analyzed

We worked at defining inter/intra-examiner reproducibility, construct validity using other scoring tools or scales found in the literature as well as an inter-item correlation matrix, responsiveness to change during hospitalization or according to the postoperative delay, and we identified a correlation between a low score and clinical complications as well as the correlation between a high score and getting back to competition.

1.2.3.1

Reproducibility

The aim is to determine the quality of the inter- and intra-examiner reproducibility of the PPLP scoring scale between two different examiners and for the same examiner.

For the inter-examiner reproducibility, two independent examiners tested the patients separately. Then, they determined a score. The results were compared using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC).

For the intra-examiner reproducibility, the first measure was done on day D0 than a second one 24 hours later, D1. The two results subsequently compared. The examiner did not try to memorize the various measures and could not check the ones recorded the previous day. The results were compared using the ICC.

1.2.3.2

Construct validity

The objective was to determine the global differential characteristic of each item and the correlations between PPLP scoring scale and other outcome scales already used in the literature. We monitored two different populations: the first population was used to design the correlation matrix and correlate it to the IKDC Subjective Knee Evaluation Form; and the second population was used to define the relationships to other outcome scales in the literature (OAK knee evaluation, Lysholm rating score, Tegner activity scale, KOOS, Arpege and the Psychovitality Test). For correlations between the different scores, we used the Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient.

1.2.3.3

Responsiveness to change

The objective was to determine the score’s potential changes during one given hospital stay, and according to the postoperative delay, thus better refining the PPLP scoring scale’s relevance according to these parameters.

We evaluated the responsiveness to change during the patients’ hospital stay. The patients during the postoperative stage were administered the PPLP1 scoring scale: once in the middle of their hospital stay and once upon leaving the hospital. For the patients cared for at the CERS rehabilitation center at a distance from the initial surgery, the PPLP2 was administered a first time upon admission and a second time upon departure from the rehabilitation center. We used the Wilcoxon signed-rank test to evaluate the responsiveness to change.

For the responsiveness to change according to the postoperative delay, we conducted a prospective follow-up on a large cohort of patients. The PPLP scoring scale was systematically administered upon leaving the hospital. It was correlated to the postoperative delay defined by the time period between the initial surgery and the day the PPLP scoring scale was administered. The postoperative delays were grouped by 15-day periods to compare the various groups. The Student t test was used and the effect sizes were measured.

1.2.3.4

PPLP score correlated to complicated clinical outcomes

The aim was to determine if there was a correlation between the PPLP score and complicated clinical outcomes. The physician in charge of the patient filled out a specific grid for monitoring clinical complications. This grid included several items that were grouped into larger categories: complex regional pain syndrome Type 1 (CRPS1or reflex sympathetic dystrophy syndrome), pain, stiffness, amyotrophy, and other clinical complications. Pain was reported when there was a functional impact and/or when the score on the numerical rating pain scale was above or equal to 3. The diagnosis of stiffness was established if the knee flexion deformity was above 5° or if the flexion was below 110° between month 1 and month 3 postoperative. Synovial effusion was mentioned if the patella perimeter was superior by at least 2 cm compared to the healthy side. Amyotrophy was reported if the thigh circumference was at least 3.5 cm smaller, measure taken at a distance of 10 to 15 cm from the upper part of the patella. Some complications were excluded from the study such as deep bacterial infections or knee instability, since they required emergency surgery and thus the PPLSP scoring scale could not administered due to the situation. Other complications such as superficial bacterial infection and phlebitis were excluded. The PPLP1 results for each group were compared using the Student t test.

1.2.3.5

The relevance of the PPLP scoring scale as a predictive tool for getting back to sport competition

The objective was to assess the impact of the advices given to the patients when they reached a PPLP score greater than 170, and to redefine the correlation between the PPLP score and getting back to competition. We analyzed the PPLP2 scores of patients that came to the CERS rehabilitation center for “muscular strengthening training” stays in 2003, 2004 and 2005. We conducted a prospective follow-up of these patients regarding their return to competition by sending them a self-administered questionnaire a year after they left the center. The response rate to the questionnaire was 50.1%. We included the patients that were cared for in our rehabilitation center at least 3.5 months after their initial surgery. All patients had an evaluation using the PPLP2 scoring scale upon leaving the CERS rehabilitation center and they were given proper advices from medical professionals according to their specific score. We aimed at evaluating the impact of these advices on the patient’s return to competition when the PPLP2 score was above 170. We also analyzed the data with the Student t test; sensitivity, specificity and we elaborated a receiving operating characteristic (ROC) curve to redefine the optimal score to be reached in order for athletes to get back to competition.

1.3

Results

1.3.1

Reproducibility

1.3.1.1

Inter-examiner

We followed 31 patients: 21 during their postoperative stay and 10 at a distance from the initial surgery. For PPLP1, the ICC is 0.92. For PPLP2, the ICC is 0.99.

1.3.1.2

Intra-examiner

We followed 26 patients: 20 during their postoperative stay and six at a distance from the initial surgery. For PPLP1, the ICC is 0.97. For PPLP2, the ICC is 1.

1.3.2

Construct validity

1.3.2.1

Correlation matrix

The objective was to verify that all items included in the PPLP scoring scale were distinctly different from one another (differential characteristics). Two items were deemed similar when their correlation was greater than 0.7. The population included 763 patients, 613 men for 150 women, mean age 27.4 years including 9% international-level athletes, 40.7% national-level athletes and 50.3% regional-level athletes. The mean correlation for PPLP1 score is r = 0.18 and for PPLP2 score r = 0.20. In addition, the item “overall pain” was differentiated from the item “pain in the graft area” ( r = 0.12). The strongest correlation for the final PPLP1 score was found for the item “sensation”, and for the final PPLP2 score with the isokinetic testing (0.6 to 0.74).

1.3.2.2

Correlation to other scoring scales and outcome scales found in the literature

1.3.2.2.1

PPLP1 and PPLP2 with the IKDC Subjective Knee Evaluation Form

We also followed this same cohort of 763 athletes (competition level) and we compared it to the IKDC Subjective Knee Evaluation Form. For the 521 inpatients in postoperative care, the correlation was 0.48 between PPLP1 (with a mean of 92.75 ± 6.59) and IKDC Subjective Knee Evaluation Form (61.89 ± 11.66). For the 242 patients who were administered the scoring scale at a distance from their initial surgery, the correlation between PPLP2 (174 ± 19.34) and IKDC Subjective Knee Evaluation Form (82.52 ± 10.34) was 0.59.

1.3.2.2.2

PPLP1 scoring scale compared to OAK knee evaluation, Lysholm rating score and the Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score

We monitored 29 patients at a mean delay of 42 days post-surgery (± 27.2), this population was made of athletes at a competition level, including 12 at national level and 17 at regional level. The mean PPLP1 score was 94 (± 4.59, range 82–100).

For the OAK knee evaluation, the mean score was 78.1 (± 5.85, range 70–92). The correlation between OAK and PPLP1 was r = 0.42.

For the Lysholm rating score, the mean score was 81.2 (± 8.46, range 71–97). The correlation between Lysholm and PPLP1 was r = 0.42.

The KOOS includes five different scoring subscales. The subscale “other symptoms” was hardly correlated with r = 0.02. The correlation between the subscale “pain” and PPLP1 was r = 0.42, for the subscale “Function in daily living (ADL)”, the correlation was r = 0.41, for the subscale “Function in Sport and Recreation (Sport/Rec)” the correlation was r = 0.5 and finally for the KOOS subscale “knee-related Quality of Life (QOL)” the correlation was r = 0.43.

1.3.2.2.3

PPLP2 compared to Arpege, Tegner activity scale and the Psychovitality test

We followed 16 patients, athlete competitors, including two at international level, eight at national level and finally six at regional level; the mean postoperative delay was 189 days (± 26.5). The mean PPLP2 score was 176 (± 30.85, range 114–200).

For Arpege, the mean score was 3.56 (± 0.1, range 3–4). The correlation between Arpege and PPLP2 was 0.76.

For the Tegner activity scale, the mean score was 6.3 (± 1.85, range 4–10). The correlation between Tegner and PPLP2 was 0.35.

For the Psychovitality test, the mean score was 16.2 (± 1.16, range 14–17). The correlation between the Psychovitality test and PPLP2 was 0.5.

1.3.3

Responsiveness to change

1.3.3.1

During the hospital stay of one given patient

During the postoperative phase, 15 patients were evaluated using the PPLP1 scoring scale: a first time 15 days after their surgery and a second time 30 days after. The mean score at D15 was 81.6 (± 4.30, range 72–88) and at D30 the mean score was 95.8 (± 4.36, range 82–97) with a significant difference of p = 0.00065 and an effect size of 3.3. The main increase was noted on the items “patella perimeter”, “pain”, “knee flexion” and giving up crutches/canes.

For the 10 patients between D45 and D90 post-surgery, PPLP1 upon admission was on average 89.6 (± 5.47, range 78–97) whereas upon leaving the hospital PPLP1 score was 95.7 (± 3.96, range 86–100) with a significant difference of p = 0.038 and an effect size of 1.11.

For the 13 patients who were on average at a postoperative delay of 5 months, the mean PPLP2 score at the beginning of their stay went from 154.4 (± 11.83, range 138–175) to 186.6 (± 10.81, range 171–200) at the end of their stay with a significant difference of p = 0.00147 and an effect size of 2.72.

1.3.3.2

According to the postoperative delay

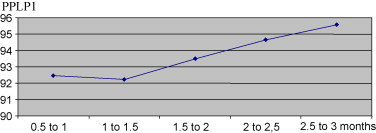

We evaluated 3331 patients at the end of their hospital stay using the PPLP1 scoring scale, 2355 men and 976 women, with a mean age of 25.3 years, including 48.8% regional-level athletes, 44.7% national-level athletes and 6.5% international-level athletes. Every 15 days on average, we observed a 1-point increase of the mean PPLP1 score according to the postoperative delay up to the first 3 months postoperative. The following scores were noted according to the postoperative delay: 92.5 (± 5.76 and n = 987) corresponding to D15 to M1; 92.5 (± 6.36 and n = 977) corresponding to M1 to M1.5; 93.5 (± 5.78 and n = 216) corresponding to M1.5 to M2; 94.5 (± 5.77 and n = 131) corresponding to M2 to M2.5 and finally 95.6 (± 4.5 and n = 104) corresponding to the postoperative delay M2.5 to M3. In spite of this moderate score increase, the difference is highly significant with p = 0.00022 between 1 to 3 months postoperative, and an effect size of 0.53. It is significant with p = 0.005 between 15 days to 1 month and 1.5 month to 2 months. Finally, it is also significant with p = 0.04 between 1.5 month to 2 months and 2 to 2.5 months. The difference is set at p = 0.08 between 2 to 2.5 months and 2.5 to 3 months ( Fig. 1 ).

We evaluated 1442 patients who were administered the PPLP2 scoring scale at the end of their CERS rehabilitation stay, at a distance from the initial surgery. The population was made of 1103 men and 339 women, with a mean age of 24.7 years, including 38.9% regional-level athletes, 51.5% national-level athletes and 9.5% international-level athletes.

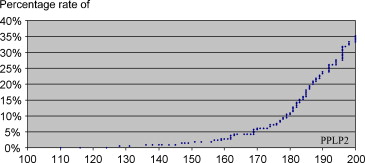

The postoperative delay between the 3rd and 4th month corresponds to a crucial time period, where the patient starts the isokinetic training and gets back to jogging/running. The PPLP2 scores during this period were lower (160 ± 18.4 between 3.5 and 4 months) with a significant difference ( p = 0.0002, and an effect size of 0.63) compared to the scores obtained after M4 post-surgery (171.6 ± 16.89 between 4 and 4.5 months). This underlines quite well the progression made by patients during the various stages of their rehabilitation-training program.

During the postoperative delay comprised between M4 and M9, the score globally increased from 171.6 (± 16.89), between M4 to M4.5, to 182.1 (± 19.47) between M8.5 to M9. This difference is significant with p < 0.0003, and an effect size of 0.62. The increase is regular every 15 days ranging from 1 to 4 points ( Fig. 2 ). However, it is not significant from one fortnight to the next ( Table 1 ).

| Postoperative delay (in months) | Number of patients | Mean PPLP2 ± standard deviation |

|---|---|---|

| 4 to 4.5 | 85 | 171.6 ± 16.89 |

| 4.5 to 5 | 119 | 173.1 ± 19.69 |

| 5 to 5.5 | 163 | 175.6 ± 18.65 |

| 5.5 to 6 | 187 | 174.1 ± 18.85 |

| 6 to 6.5 | 208 | 176.8 ± 17.63 |

| 6.5 to 7 | 168 | 177.6 ± 18.22 |

| 7 to 7.5 | 127 | 177.5 ± 18.72 |

| 7.5 to 8 | 94 | 178.8 ± 16.33 |

| 8 to 8.5 | 57 | 178.4 ± 14.29 |

| 8.5 to 9 | 39 | 182.1 ± 19 |

1.3.4

Relevance of the PPLP scoring scale for follow-up of clinical complications after ACL reconstruction

We analyzed the clinical evolutions of 3296 ACL reconstructions during the postoperative stay among 3331 patients of the initial population that benefited from PPLP1 assessment (98.9%), 2321 men and 975 women, mean age 25.3 years, 48.8% were regional-level athletes, 44.7% national-level athletes and 6.5% international-level athletes.

The lower scores ( Table 2 ) were reported in the group “CRPS1” with a mean PPLP1 at 80.33 (± 9.76). The mean PPLP1 scores of the groups “pain” and “stiffness” were respectively 85.48 (± 6.94) and 85.40 (± 6.5). The “synovial effusion” group had a mean score of 86.13 (± 6.42). The “amyotrophy” group had a mean score of 88.78 (±4.95), whereas the group “other complications” had a mean score of 85.86 (±13.40). The “no complications” group had the highest mean score with 94.28 (± 4.68).

| Clinical evolution | Mean PPLP1 ± standard deviation | Minimum/maximum | Number (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRSP1 | 80.33 ± 9.76 | 53/98 | 63 (1.9) |

| Pain | 85.48 ± 6.94 | 66/98 | 143 (4.3) |

| Stiffness | 85.40 ± 6.5 | 69/98 | 86 (2.6) |

| Synovial effusion | 86.13 ± 6.42 | 67/96 | 62 (1.9) |

| Amyotrophy | 88.78 ± 4.95 | 67/98 | 258 (7.8) |

| Other complications | 85.86 ± 13.40 | 63/96 | 20 (0.6) |

| No complications | 94.28 ± 4.68 | 56/100 | 2664 (80.8) |

There is a highly significant difference ( p < 0.0001) between the “CRPS1” groups compared to all other groups. There is also a highly significant difference ( p < 0.0001) between the “pain” group or “stiffness” group compared to the “amyotrophy” group and the “no complications” group. The group “synovial effusion” was statistically different from the “amyotrophy” group with p = 0.007 and from the “no complications” group with p < 0.0001. However, we noted no statistical difference between the “pain”, “stiffness” and “synovial effusion” groups with reported scores that were quite similar.

A low score is thus correlated to clinical complications. PPLP1 is a relevant scoring scale for the monitoring and follow-up of patients during their postoperative phase and a good predictive factor of clinical complications.

1.3.5

Relevance of the PPLP score as a predictive factor for getting back to competition

We followed a cohort of 258 patients, 186 men and 73 women, with a mean age of 29.7 years, 47.1% of them were involved in regional competitions, 43.3% in national competitions and 9.6% in international competitions.

At the time of the study 1 year after their “reinforcement” training stay in a rehabilitation center, 79.8% ( n = 206/258) went back to competition and 20.2% did not, for a postoperative delay of about 18 months (18.5 months ± 1.9). The mean PPLP2 score upon leaving the rehabilitation center was 177.12 (± 18.32, range 140–200) for those who went back to competition whereas for patients who did not get back to competition (20.2%), the mean PPLP2 score upon leaving the rehabilitation center was 169.5 (± 19.22, range 141–200). The difference is significant with p = 0.012. The PPLP2 score is thus correlated to the possibility of getting back to competition.

At 2.5 months after completing the scoring scale, the shape of the graph ( Fig. 3 ) validates the correlation between a high score and getting back to competition. We created different groups to statistically validate this graph but mostly to analyze the time delay between completing the PPLP2 scoring scale and getting back to competition. We calculated the mean PPLP2 scores of several groups according to the delay in getting back to competition after completing the PPLP2 score: 0 to 1.5 month, 1.5 to 2.5 months, 2.5 to 4 months, 4 to 6 months and 6 to13 months. The earlier the athletes returned to competition, the higher the mean score was for each group ( Table 3 ). The statistical difference between those who returned to sport competition before 1.5 month and those who went back between 1.5 and 2.5 months is p = 0.08. The difference between the first and third group is significant with p = 0.041, it is also significant between the first and fourth group ( p = 0.017) and the fifth group ( p < 0.0001). The difference is significant between the fifth and third group ( p = 0.005), and the fifth and fourth group ( p = 0.02). However, there is no difference between the second and third group or between the third and fourth group. There is noticeable correlation between a high score and getting back to competition.

| Delay of getting back to competition after completing the score (months) | Number | Mean PPLP2 score ± standard deviation |

|---|---|---|

| 0 to 1.5 | 41 | 185.1 ± 14.59 |

| 1.5 to 2.5 | 22 | 178.5 ± 14.72 |

| 2.5 to 4 | 50 | 178.26 ± 16.52 |

| 4 to 6 | 49 | 176.4 ± 18.11 |

| 6 to 13 | 40 | 166.65 ± 20.96 |

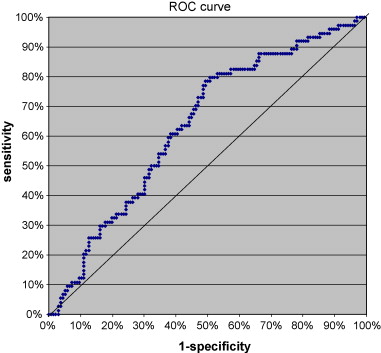

The PPLP2 score described in the literature as the minimum acceptable score for getting back to sports competition is 170. Our goal was to have a better understanding of the real impact of the advices given to patients who reached this threshold score of 170 by analyzing its sensitivity and specificity through the rate of patients that went back to competition 2.5 months after completing the PPLP2 scoring scale. We found a sensitivity of 83.8% and a specificity of 35.3% for a global score associating sensitivity and specificity of 119.1. These results are moderate. We then looked at redefining the optimal threshold point. Using the ROC curve ( Fig. 4 ), we recalculated the most interesting score. We found that this score was 176 instead of 170, as previously suggested. Thus, if we consider a PPLP2 score of 176 compatible with getting back to competition, the sensitivity is 79.7% and specificity 49.3%, for a total score of 129.

Nevertheless, in spite of the correlation between the PPLP2 score and getting back to competition, only 37.9% of patients reaching that 176 score got back to competition at a postoperative delay of 2.5 months after completing the PPLP2 scoring scale.

In conclusion, the PPLP2 score is correlated to the possibility of getting back to competition, and a high score is correlated to a faster return. The optimum threshold score is 176. However, the score is poorly discriminating in regards to sensitivity, specificity and percentage of athletes getting back to competition 2.5 months after completing the scoring scale.

1.4

Discussion

In the international literature, the Lysholm and Tegner rating score is the most commonly found tool , it is used in 84% of clinical trials . It is also the rating score of reference in comparative studies . The OAK knee evaluation seems to have a good clinical correlation . Arpege is the most used French language scale at a national level . The KOOS is more frequently reported in the latest international literature due to its validation in English by Swedish researchers . Furthermore, the IKDC Subjective Knee Evaluation Form is being used more since the work of Irrgang , it is easy to use and was properly validated . In our clinical practice, we also use the IKDC in addition to the PPLP scoring scale, because it is appropriate for evaluating the patients’ feelings as well as their functional abilities.

We validated the differential characteristic of each item in the PPLP scoring scale grid. The commonly used assessment scales were not validated through the use of a correlation matrix. Regarding “pain”, this item could seem quite similar to the one from the clinical exam looking for “pain in the graft site”. However, the correlation coefficient ( r = 0.12) validates the differentiation between these two items. We excluded some items from this study, as they were not appropriate for obtaining a scoring scale, such as objective knee instability or deep bacterial infection since they required emergency surgery. This is probably one of the scoring scale’s limits not allowing for a real quantification of these clinical complications that are in fact surgical failures. These items would need to be taken into account for further modifications to the PPLP scoring scale. Sometimes, the validity of the scales found in the literature was analyzed using the reference scale SF36 ; this is the case for the KOOS and Lysholm evaluation scales . However, this scale focuses essentially on the QOL and psychological state. Its relevance is quite low for the follow-up of ACL reconstruction patients. This is why, like many other authors , we compared directly the tools used for the follow-up of ACL reconstruction one to the other and we reported comparable results. The correlations between the various scoring scales can vary. Apart from the KOOS scoring subscale “other symptoms”, the correlation is fair going from 0.3 to 0.59. It is good with Arpege r = 0.76. Thus, the varying correlations between the different scoring scales probably emphasize the complementary nature of these different follow-up outcome scores. The advantage of the PPLP scoring scale in regards to other tools is the ability to include in the same score a postoperative clinical assessment close to the Lysholm rating score or OAK knee evaluation, but also an evaluation at a distance from surgery just like the Arpege scale or Tegner activity scale.

In spite of being largely used in France , Arpege is barely used in the Anglo-Saxon literature (4% according to Johnson et al. ). This classification was rarely evaluated. This is also the case with the OAK knee evaluation. The other scales were properly evaluated with a proper methodology regarding reproducibility: two studies reported very high ICCs ranging from 0.88 to 0.95 for the Lysholm rating score and the Tegner activity scale . The reproducibility validation was calculated on 16 patients for the Lysholm rating score , which is lower than our population of 26 patients for the intra-examiner reproducibility, and even 31 patients for the inter-examiner reproducibility. Bengtsson et al. were also interested in the validity of the Lysholm scale . Another study showed a good reproducibility for the KOOS with an ICC of 0.85 for the subscale “pain”, 0.93 for the subscale “other symptoms”, 0.75 for the subscale “Function in Daily Living”, 0.81 for the subscale “Function in sport/rec” and 0.86 for the subscale “knee-related QOL” . Finally, a study conducted by Irrgang and Shelbourne showed an excellent reproducibility for the IKDC Subjective Knee Evaluation Form with an ICC of 0.94 . We also obtained excellent ICCs for the PPLP scoring scale both for intra and inter-examiner reproducibility. The PPLP scoring scale can be used by the same examiner or by two different examiners with a good reproducibility. It has been validated in the French language, which is usually not the case for the other outcome scores.

Risberg et al. focused on the responsiveness to change for the Lysholm scoring system, IKDC Subjective Knee Evaluation Form and Cincinnati score, but in most cases this responsiveness to change was not largely studied . For the KOOS, the responsiveness to change showed effect sizes going from 0.86 to 1.65 . For our study, they varied between 0.53 and 3.3. Irrgang showed that a variation of 11.5 or 20.5 was necessary to a have an optimal specificity or responsiveness to change for the IKDC Subjective Knee Evaluation Form. Furthermore, Nunes and Pascoa Pinheiro reported the low responsiveness to change over time for the Lysholm rating score . In our study, during the athletic patients hospital stay, the PPLP score had progressed in a statistically significant manner. According to the postoperative delay, the PPLP score progressions varied. We reported a very strong progression in the first month postoperative between patients before D15 and those after D15. This phase corresponds to a decrease of the inflammation, improvement in joint ROM and functional abilities. The end of medication and discarding English canes also played a role in the score progression. Afterwards, 45 days postoperative, the score increased significantly with minimal variations (a few points only). This phase corresponds to a waiting period in terms of rehabilitation when few new training exercises are implemented until the start of running/jogging exercises around the 3rd or 4th month. It was during this time period that the PPLP2 score had the greatest increase. Then it increased progressively with the improvement of muscular capacities and decrease in muscular strength impairments during isokinetic testing. Thus, even if the score tends to progress towards a plateau at 1 month post-surgery and again at 5–8 months post-surgery, there is a certain responsiveness to change according to the postoperative delay even during these time periods.

If Barber-Westin and Noyes analyzed the correlation between the Cincinnati rating score and the physician’s impression of severity, to our knowledge, the rating scales found in the literature were rarely assessed with this parameter. However, this element is essential: knowing if the follow-up tool can properly measure the differences between a normal clinical evolution and a complicated clinical evolution. This is why we defined this criterion for the PPLP tool. The score can statistically differentiate clinical complications such as “CRPS1” (mean PPLP1 at 80); pain (mean PPLP1 at 85), stiffness (mean PPLP1 at 85), synovial effusion (mean PPLP1 at 86) from a difficult clinical evolution such as amyotrophy (mean PPLP1 at 88) from a normal clinical evolution (mean PPLP1 at 94). Even though amyotrophy can be discussed as a relevant criterion, it can be the image of an inability to start active rehabilitation training and thus lead to potential complications preventing muscular reinforcement. We kept this criterion as part of the analyzed score in spite of its low specificity. The PPLP1 score is statistically lower for CRPS1 than for other complications, this underlines the severity of this complication. However, if the score is a proper indicator for follow-up, it cannot replace the clinical diagnosis established by a physician that will determine the pathology. A low PPLP1 score could be a good indicator to justify referring the patient towards a medical or surgical specialist.

If ACL tearing mechanisms are better understood , opinions differ regarding the necessary delay before getting back to sport practice , due to the poor knowledge of the real risks involved in ACL reconstruction recovery. The commonly agreed postoperative delay for getting back to competition in France is between 8 to 12 months , whereas Irrgang authorizes sporting activities after 6 months post-surgery if the clinical evaluation of the knee is perfect, if the isokinetic impairment does not go over 20% and if the patient passes the following functional tests: hop tests for distance (single-leg hop, triple cross-over hop). However, these functional tests, such as running tests, vertical jumps, hop tests for distance and stability tests, do not always have well-defined goals and according to Barber-Westin and Noyes the only valid, reliable and reproducible test is Daniel’s single-leg hop test for distance. Shelbourne et al. report that the athlete can get back to sport activities between the 2nd and 5th month postoperative with a knee brace for stability. Under the following conditions: patient gained back normal ROM especially symmetric extension, significant improvement of muscular strength during isokinetic evaluation and the patient followed an intensive physical rehabilitation training program. Glasgow et al. study report that athletes can resume sport activities right from the 3rd month, if the Lachman test is negative and the patient motivated. Glasgow et al. assume that if all the above-listed criteria are met, the ligament-bone graft is consolidated.

To this day however the criteria for getting back to competition are still badly defined due to the lack of studies confirming or denying these hypotheses and we demonstrated that in France we remain quite cautious about the postoperative delays . None of the other scoring tools can predict the possibilities to get back to sport competition or define adequate postoperative delays. This is why we aimed at defining the correlation between advices given to athletes who reached a certain PPLP score and getting back to competition. We also tried to determine if another threshold score was a predictive factor for getting back to competition. We reported that the PPLP2 score was correlated to the possibility of getting back to competition. There is a significant difference between the scores of athletes getting back to competition and those who do not. A high score is linked to a high return rate to competition and a shorter postoperative delay. We were able to determine the optimal predictive score for getting back to competition 2.5 months after completing the PPLP2 scoring scale. This threshold score is 176. However, this score is moderately discriminating in regards to responsiveness to change, specificity and competition return rate. We must remain cautious in the interpretation of this threshold score, because its definition might be influenced by the advices given to the athletes on getting back to competition in accordance to the score result. Other criteria not studied by the PPLP scoring scale also have a potential impact in resuming sport activities such as postoperative delay, the athlete’s level, age, gender, type of sport, sport agenda, motivation or even the type of surgical procedure or the time delay defined by the surgeon or sport physician.

We conducted several prospective studies to define the various degrees of validity of the PPLP scoring scale. However one unique prospective study on the same population between 2003 and 2007 would have been ideal for the statistical analysis of the various data. We designed the various studies according to the objectives defined in order to limit the risk of statistical biases. The follow-up conducted with a self-administered questionnaire with a return rate of 50.1% brings some limitation regarding the results’ interpretation for getting back to competition. The population of responders and non-responders are similar in terms of age, gender, athletic level and sport practice; this limits the risk of statistical biases. The comparison between the IKDC Subjective Knee Evaluation Form and the PPLP scoring scale is one of the largest series available in the literature. Moreover, we focused on validation parameters for the PPLP tool that was hardly reported in other scoring tools found in the literature. The PPLP scoring tool is simple to use, its final result is available in one single number, unlike the KOOS that requires a complex calculation. The PPLP scoring scale allows for a proper monitoring of the rehabilitation program that is highly relevant for the follow-up of ACL reconstruction patients. Further studies with the PPLP tool will focus on comparing the evolution of the various surgical techniques. A weak PPLP1 score could entice the physician to change the patient’s rehabilitation therapeutic care. For PPLP2, isokinetic tests have a good correlation to the final score validating the good synthesis of the various impairments according to the speeds all analyzed in one variable: an essential element to imagine the predictive nature of the score on an eventual return to competition. Conversely, integrating the results of an isokinetic test is a limitation to its use by physiotherapists in their private practice since it requires the acquisition of expensive equipments. Furthermore, all medical teams do not perform isokinetic testing in eccentric mode. The lack of an eccentric evaluation leads to a low score that has a negative impact on the final score. We can also regret that the PPLP scoring scale is divided into two parts and not just one part with a total of 200 points. Finally, other items could be identified and integrated during later modifications to the PPLP content in order to define their real impact in the decision-making process of letting the athlete get back to competition, like proprioceptive evaluation but also postoperative delay, athletic level, type of sport or the type of surgical procedure. It would also be quite relevant to conduct additional studies to evaluate the impact of isokinetic impairments on resuming running/jogging and sport practice.

1.5

Conclusion

We demonstrated the relevance of the PPLP scoring scale for ACL reconstruction follow-up mainly during the postoperative phase and after 3–4 months postoperative to better understand the required time delays for getting back to competition. This tool is reproducible and its items are differentiated. Its responsiveness to change is good during the hospital stay and fair according to the postoperative delay with time periods that are more responsive to change than others. A low score is correlated to clinical complications or difficult postoperative recovery. The PPLP scoring scale is above all else indicated as a follow-up tool for monitoring ACL reconstruction patients, but PPLP2 also gives some indications on the quality of the recovery and the possibilities of getting back to competition.

2

Version française

2.1

Introduction

Si de nombreuses échelles de suivi des ligamentoplasties du ligament croisé antérieur (LCA) existent , peu ont réellement été évaluées avec une méthodologie complète . Le plus souvent, chaque auteur se limite à l’analyse d’un seul des paramètres de validité, entraînant une diversité d’études difficiles à comparer pour déterminer la supériorité d’un score par rapport à l’autre . De plus, bien que les évaluations isocinétiques soient fréquemment utilisées pour le suivi des ligamentoplasties , elles ne sont jamais intégrées dans une échelle de suivi. Le score PPLP a été peu décrit dans la littérature et n’a pas été validé. Ce score permet de réaliser un suivi des ligamentoplasties du LCA et d’évaluer les possibilités de reprise du sport ( Annexe A ). Il s’appuie sur des éléments subjectifs, cliniques, fonctionnels ainsi qu’un bilan de la force musculaire. La grille est composée de deux parties : l’une (PPLP1) pour un suivi postopératoire et l’autre (PPLP2) qui s’additionne au premier score pour un suivi à distance de la chirurgie déterminant ainsi un nouveau score. Notre objectif a donc été d’évaluer sa reproductibilité, sa validité, sa sensibilité au changement et sa pertinence dans le suivi des ligamentoplasties du LCA.

2.2

Patient et méthode

2.2.1

Score PPLP

Le score PPLP1 ( Annexe A ) est défini par des paramètres subjectifs (douleur, appréhension et impression du patient) associés à des paramètres d’examen clinique (le périmètre rotulien, les tests de laxité articulaire, les amplitudes articulaires, la douleur sur le site de prélèvement et l’amyotrophie). Il prend également en compte un paramètre fonctionnel simple comme la marche avec ou sans aide technique et la prise médicamenteuse. Le PPLP1 permet le suivi des patients en postopératoire et est maximal pour un score 100 points.

Le score PPLP2 ( Annexe A ) est défini par une évaluation fonctionnelle (course, travail cardiovasculaire sur bicyclette) et une évaluation isocinétique. Ce score s’ajoute au PPLP1 pour déterminer un score sur 200 points au maximum. Le délai opératoire est défini par le délai entre la chirurgie et le moment de la réalisation du score. Les tests isocinétiques sont réalisés sur le quadriceps et les ischiojambiers en mode concentrique à la vitesse de 90°/s (six répétitions) et 240°/s (15 répétitions), puis en mode excentrique à 90°/s (six répétitions) sur appareil d’isocinétisme de type Biodex après un échauffement sur vélo, leg-press et travail des ischiojambiers d’environ 15 minutes complété par deux à trois mouvements initiaux d’échauffement sur l’appareil d’isocinétisme. La position du patient est assise, avec un débattement articulaire de genou allant de 0 à 90°. Les bras sont en position sur les poignées latérales. L’ensemble du test est réalisé par le même opérateur, qui est expérimenté. La durée totale du test est d’environ 30 à 40 minutes. La quantification du déficit de pic de couple (ou moment maximal) entre le côté opéré et le côté sain permet le calcul du score PPLP2.

2.2.2

Méthode

Notre étude s’est déroulée en plusieurs phases prospectives entre 2003 et 2009, afin d’aborder les différents aspects nécessaires à la validation du score. La multiplicité des critères de validation et des modes de mesures (suivi clinique, questionnaire) ont nécessité plusieurs études distinctes en fonction des degrés d’exigences de validation de chaque critère. De courtes périodes de suivi avec faibles effectifs ont permis de comparer le PPLP avec d’autres scores de la littérature, d’analyser la reproductibilité et la sensibilité au changement au cours de l’hospitalisation. De longues périodes de suivi avec de larges effectifs permettent d’observer de minimes variations statistiques, en ce qui concerne la sensibilité au changement en fonction du délai opératoire, la corrélation avec des complications et la reprise du sport. De plus, compte tenu de la partie du score PPLP à valider, nous avons également cherché à distinguer deux types de population : l’une composée de patients en postopératoire pour le PPLP1 et l’autre composée de patients à distance de l’intervention pour le PPLP2. Nous avons corrélé le PPLP aux scores de la littérature les plus fréquents suivant la période postopératoire : le PPLP1 avec l’OAK, le Lysholm, le KOOS et le PPLP2 avec le Tegner, l’Arpège et le Psychovitality test . Par ailleurs, nous avons analysé les complications à travers le PPLP1, puisque la période postopératoire est celle la plus pertinente pour observer d’éventuelles complications sans biais de recrutement. De même, nous n’avons corrélé que le PPLP2 à la reprise du sport, puisque seuls les patients à distance de l’intervention sont concernés par cette dernière.

Le critère d’inclusion est la chirurgie du LCA chez des sportifs de niveau minimum régional, national ou international. Ont été inclus toutes les techniques chirurgicales de ligamentoplasties du LCA. Les critères d’exclusion sont les chirurgies complexes, telles une lésion associée du ligament croisé postérieur, une ostéotomie ou un polytraumatisme. Ont été également exclu certaines complications comme les sepsis profonds ou les accidents d’instabilité, car ils entraînaient une reprise chirurgicale en urgence et le score PPLP n’était alors pas réalisé au vu du contexte.

Les analyses statistiques ont été réalisées avec le logiciel Statistical Analysis System (SAS) version 9,1 avec l’aide d’une statisticienne. Le seuil de significativité retenu pour les tests d’hypothèse est une valeur p inférieure à 0,05.

2.2.3

Les différents paramètres analysés

Nous avons cherché à définir la reproductibilité inter- et intra-examinateur, la validité de construit à travers d’autres scores de la littérature et une matrice de corrélation inter items, la sensibilité au changement au cours de l’hospitalisation ou en fonction du délai opératoire et de déterminer une corrélation entre un score bas et une complication ou un score élevé et la reprise du sport.

2.2.3.1

La reproductibilité

L’objectif est de déterminer la qualité de la reproductibilité du score PPLP entre deux examinateurs différents et pour le même examinateur.

Pour la reproductibilité interexaminateur, deux examinateurs indépendants ont examiné les patients de façon séparée. Ils ont ensuite déterminé un score. Les résultats ont été comparés grâce au coefficient de corrélation intraclasse (ICC).

Pour la reproductibilité intra-examinateur, une première mesure a été réalisée au jour j0 puis une seconde à 24 heures d’écart. Les deux résultats ont ensuite été comparés. L’examinateur ne cherchait pas à mémoriser les diverses mesures et ne pouvait vérifier celles du jour précédent. Les résultats ont été comparés grâce au coefficient de ICC.

2.2.3.2

La validité de construction

L’objectif est de déterminer le caractère différencié global des différents items et les corrélations entre le score PPLP et d’autres scores déjà utilisés dans la littérature. Nous avons suivi deux populations avec des effectifs différents : l’une pour construire la matrice de corrélation et la comparaison à l’IKDC subjectif, puis l’autre pour préciser les liens avec d’autres scores de la littérature (OAK, Lysholm, Tegner, KOOS, Arpège et Psychovitality Test ). Pour les corrélations entre les différents scores, le coefficient de corrélation de Spearman a été utilisé.

2.2.3.3

La sensibilité au changement

L’objectif est de déterminer les variations potentielles du score au cours d’une même hospitalisation et en fonction du délai opératoire, permettant de mieux préciser l’intérêt du score suivant ces paramètres.

La sensibilité au changement pendant l’hospitalisation a été évaluée. Les patients en postopératoire ont été évalués par le score PPLP1 : une fois en milieu d’hospitalisation et une fois au moment de la sortie. Pour ceux pris en charge au CERS à distance de l’intervention, le PPLP2 a été réalisé à l’entrée et à la sortie de l’hospitalisation. Le test statistique utilisé pour évaluer le changement est le test de Wilcoxon pour échantillons appariés.

Pour la sensibilité au changement en fonction du délai opératoire, nous avons suivi de façon prospective une large série de patients. Le score PPLP a été réalisé systématiquement à la sortie de l’hospitalisation. Il a été corrélé au délai opératoire qui est défini par le délai entre la chirurgie et le moment de la réalisation du score. Les délais opératoires ont été regroupés par périodes de 15 jours pour comparer les différents groupes. Le test de Student a alors été utilisé et les tailles d’effet ont été précisées.

2.2.3.4

La corrélation du score PPLP avec les évolutions cliniques compliquées

L’objectif est de déterminer s’il existe une corrélation entre le score du PPLP et les évolutions cliniques compliquées. Une grille de suivi des évolutions cliniques compliquées a été renseignée par le médecin responsable du patient. Cette grille retenait de nombreux items qui ont été regroupés en grandes classes : la neuro-algodystrophie (syndrome douloureux régional complexe de type 1 [SDRC1]), la douleur, la raideur, l’amyotrophie et les autres évolutions cliniques difficiles. Les douleurs ont été retenues en cas de retentissement fonctionnel et/ou d’une échelle numérique de la douleur (EN) supérieure ou égal à 3. Le diagnostic de raideur a été porté en cas de flexum supérieur à 5° ou de flexion inférieure à 110° entre le premier mois et le troisième mois en postopératoire. L’hydarthrose a été mentionnée en cas de périmètre rotulien supérieur à 2 cm par rapport au côté controlatéral. L’amyotrophie a été signalée en cas de différence de tour de cuisse à 10 ou 15 cm du bord supérieur de la rotule d’au moins 3,5 cm. Ont été exclu de l’étude certaines complications comme les sepsis profonds ou les accidents d’instabilité, car ils entraînaient une reprise chirurgicale en urgence et le score PPLP n’était alors pas réalisé au vu du contexte. Ont été également exclu les sepsis superficielles et les phlébites. Les résultats des PPLP1 de chaque groupe ont été comparés en utilisant le test de Student.

2.2.3.5

La pertinence de la grille PPLP en tant qu’outil prédictif de la reprise du sport

L’objectif est de déterminer s’il existe un impact des conseils formulés au patient en cas de PPLP supérieur à 170 et de repréciser la corrélation entre le score du PPLP et la reprise du sport. Nous avons analysé les scores PPLP2 des patients venus au CERS en séjour dit de « renforcement » en 2003, 2004 et 2005. Nous suivons de façon prospective la reprise de la compétition par questionnaire adressé à un an du séjour. Le taux de réponse aux questionnaires est de 50,1 %. Nous avons retenu les patients qui ont été pris en charge par le CERS à plus de 3,5 mois de l’intervention chirurgicale. Tous ont bénéficié d’une évaluation par la grille PPLP2 à la sortie du CERS et de conseils en fonction du score. Nous avons cherché à évaluer l’impact de ces conseils sur la reprise du port lorsque le score PPLP2 est supérieur à 170. Nous avons également analysé les données à travers le test de Student, la sensibilité, la spécificité et réalisé une courbe Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) pour rediscuter le score optimal de la reprise du sport.

2.3

Résultats

2.3.1

La reproductibilité

2.3.1.1

Interexaminateur

Nous avons suivi 31 patients : 21 en postopératoire et dix à distance de l’intervention. Pour le PPLP1, le coefficient de corrélation intraclasse est de 0,92. Pour le PPLP2, l’ICC est de 0,99.

2.3.1.2

Intra-examinateur

Nous avons suivi 26 patients : 20 en postopératoire et six à distance de l’intervention. Pour le PPLP1, le coefficient de corrélation intra classe est de 0,97. Pour le PPLP2, l’ICC est de 1.

2.3.2

La validité de construit

2.3.2.1

La matrice de corrélation

L’objectif est de vérifier si les items du score ont un caractère différencié. Deux items sont indifférenciés lorsque leur corrélation est supérieure à 0,7. La population est constituée de 763 patients, 613 hommes pour 150 femmes, de moyenne d’âge 27,4 ans dont 9 % internationaux, 40,7 % nationaux et 50,3 % régionaux. La corrélation moyenne est pour le PPLP1 de r = 0,18 et pour le score PPLP2 de r = 0,20. À noter que l’item sur la « douleur » globale est différencié de l’item des « douleurs sur le site de prélèvement » ( r = 0,12). La corrélation la plus forte du score final PPLP1 est retrouvée pour l’item « impression » et pour le score final PPLP2 avec les tests isocinétiques (0,6 à 0,74).

2.3.2.2

La corrélation avec d’autres scores de la littérature

2.3.2.2.1

Le PPLP1 et le PPLP2 avec l’IKDC subjectif

Nous avons également suivi cette même population de 763 patients compétiteurs et nous l’avons comparée à l’IKDC subjectif. Pour les 521 patients en postopératoire, la corrélation est de 0,48 entre le PPLP1 (avec une moyenne de 92,75 ± 6,59) et l’IKDC subjectif (61,89 ± 11,66). Pour les 242 patients à distance de la chirurgie, la corrélation entre le PPLP2 (174 ± 19,34) et l’IKDC subjectif (82,52 ± 10,34) est de 0,59.

2.3.2.2.2

Le PPLP1 avec l’OAK, le Lysholm, le Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score

Nous avons suivi 29 patients compétiteurs, dont 12 nationaux et 17 régionaux à 42 jours de l’intervention en moyenne (± 27,2). Le score PPLP1 moyen est de 94 (± 4,59) avec des extrêmes allant de 82 à 100.

Pour l’OAK, le score moyen est de 78,1 (± 5,85) pour des extrêmes allant de 70 à 92. La corrélation entre l’OAK et le PPLP1 est de r = 0,42.

Pour le Lysholm, le score moyen est de 81,2 (± 8,46) avec des extrêmes allant de 71 à 97. La corrélation entre le Lysholm et le PPLP1 est de r = 0,42.

Pour le KOOS, il existe plusieurs scores différents. Le KOOS symptômes n’est quasiment pas corrélé avec r = 0,02. La corrélation entre le KOOS douleur et le PPLP1 est de r = 0,42, pour le KOOS FAQ la corrélation est r = 0,41, pour le KOOS FSAL r = 0,5, pour le KOOS QDV r = 0,43.

2.3.2.2.3

Le score PPLP2 avec l’Arpège, le Tegner et le Psychovitality Test

Nous avons suivi 16 patients compétiteurs, dont deux internationaux, huit nationaux et six régionaux à 189 jours de l’intervention en moyenne (± 26,5). Le score PPLP2 moyen est de 176 (± 30,85) avec des extrêmes allant de 114 à 200.

Pour l’Arpège, le score moyen est de 3,56 (± 0,51) pour des extrêmes allant de trois à quatre. La corrélation entre l’Arpège et le PPLP2 est de 0,76.

Pour le Tegner, le score moyen est de 6,3 (± 1,85) avec des extrêmes allant de 4 à 10. La corrélation entre le Tegner et le PPLP2 est de 0,35.

Pour le Psychovitality Test , le score moyen est de 16,2 (± 1,16) pour des extrêmes allant de 14 à 17. La corrélation entre le Psychovitality Test et le PPLP2 est de 0,5.

2.3.3

La sensibilité au changement

2.3.3.1

En cours d’hospitalisation chez un même patient

En postopératoire, 15 patients ont été évalués par le score PPLP1 : soit une fois à 15 jours et une autre à 30 jours de l’intervention chirurgicale. Le score moyen est à j15 de 81,6 (± 4,30 et allant de 72 à 88) contre à j30 un score moyen de 95,8 (±4,36 et allant de 82 à 97) avec une différence significative de p = 0,00065 et une taille d’effet de 3,3. Le principal gain a lieu sur les items du « périmètre rotulien », sur les « douleurs », sur la « flexion de genou » et sur l’abandon des cannes.

Pour les dix patients entre j45 et j90 de l’intervention chirurgicale, le PPLP1 du début de séjour est de 89,6 en moyenne (±5,47 et allant de 78 à 89,6) tandis qu’à la sortie le PPLP1 est de 95,7 (±3,96 et allant de 86 à 100) avec une différence significative de p = 0,038 et une taille d’effet de 1,11.

Pour les 13 patients en moyenne à cinq mois de l’opération, le score moyen PPLP2 du début de séjour est passé de 154,4 (± 11,83 et allant de 138 à 175) à 186,6 (± 10,81 et allant de 171 à 200) en fin de séjour avec une différence significative p = 0,00147 et une taille d’effet de 2,72.

2.3.3.2

En fonction du délai postopératoire

Nous avons analysé 3331 patients à la sortie de l’hospitalisation par le score PPLP1, soit 2355 hommes et 976 femmes, avec une moyenne d’âge de 25,3 ans, dont 48,8 % de régional, 44,7 % de national et 6,5 % d’international. On peut observer une augmentation tous les 15 jours d’environ un point du score moyen PPLP1 avec le délai opératoire sur les trois premiers mois avec 92,5 (± 5,76 et n = 987) pour la période de 0,5 à 1 mois, 92,5 (± 6,36 et n = 977) pour la période de un à 1,5 mois, 93,5 (± 5,78 et n = 216) pour la période de 1,5 à deux mois, 94,5 (± 5,77 et n = 131) pour la période de deux à 2,5 mois et 95,6 (± 4,5 et n = 104) pour la période de 2,5 à trois mois. Malgré cette augmentation modéré du score, la différence est hautement significative entre un et trois mois, avec p = 0,00022, avec une taille d’effet de 0,53. Elle est significative entre 0,5 à un mois et 1,5 à deux mois avec p = 0,005 et entre 1,5 à deux mois et deux à 2,5 mois avec p = 0,04. La différence est de p = 0,08 entre deux à 2,5 mois et 2,5 à trois mois ( Fig. 1 ).