Upper Extremity Regional Musculoskeletal Syndromes: Shoulder, Elbow, Wrist, and Hand

The regional disorders of the upper extremity test the diagnostic acumen and judgment of the clinician more today than ever. As we will explore in Section III, people are so wary of upper extremity discomfort that they are quicker than ever to seek care. The response of the clinical community, as we would predict, is to offer the care that seems most sensible to the particular provider. One result has been an expansion of nomenclature; old terms and new terms, terms with anatomic connotations, and terms with biomechanical or ergonomic connotations litter the literature1 and clutter the clinic. This cacophony in nomenclature will persist until someone undertakes to systematically develop a valid, reliable, and meaningful set of criteria cognizant of the fact that many of the current labels are driven by the preconceptions of the practitioners to whom the patient turns.2 Until then, interventions remain empiric and often idiosyncratic, and controversies rage. For these reasons I will discard all the familiar yet unproved and unprovable labels, causal assertions, and empiric therapies in favor of the conservative posture I advocated in Chapter 4.

SHOULDER PAIN

Unlike most causes of regional pectoral girdle pain,3 diagnostic skills can be rewarded with insights that have considerable therapeutic ramifications for the patient with a painful shoulder. All patients with regional shoulder disorders have some restriction in range of motion. If motion is unimpaired so that the patient is able to place a palm on the occiput, for example, or if motion is similar to the uninvolved side, one must question the inference of regional shoulder pain. In this setting, referred pain from multiple sites must be considered: angina and its equivalents, neck pain with or without radiculopathy, diaphragmatic pain, bone pain from metastatic disease or a Pancoast’s tumor, invasive or inflammatory disease of axillary structures, and so forth.

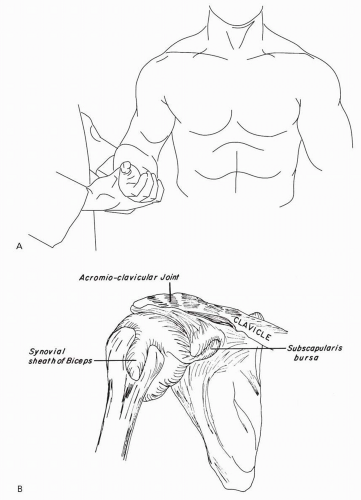

If motion is impaired, it is next crucial to discern whether the glenohumeral joint itself is involved. There is an arc of motion that isolates this articulation (Fig. 7.1). Restriction or pain in this arc indicates inflammatory disease of the true shoulder and with one exception, reflex sympathetic dystrophy (discussed in Chapter 9), excludes regional illness. The differential diagnosis of glenohumeral arthritis includes a range of inflammatory systemic rheumatic diseases, infectious arthritides, and even the exceptionally destructive osteoarthritis known as Milwaukee shoulder. The latter presents in the elderly population and is usually asymptomatic except for a rare hemarthrosis.

Shoulder Periarthritis

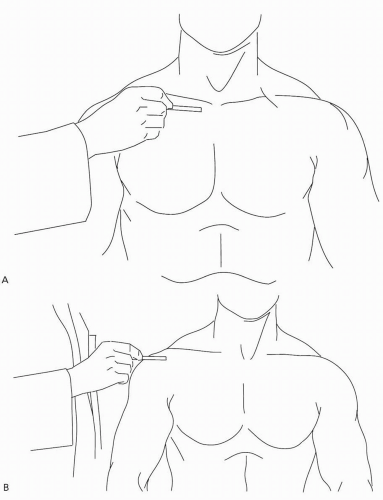

If the glenohumeral joint is spared and motion is impaired by painful restriction in other arcs, in all likelihood one is faced with a regional illness involving a structure in proximity to the glenohumeral joint. Some such structures, such as the sternoclavicular and acromioclavicular joints, are readily palpable (Fig. 7.2); if frank inflammation (synovitis) is discerned, the diagnostic likelihoods revert to those for glenohumeral disease.

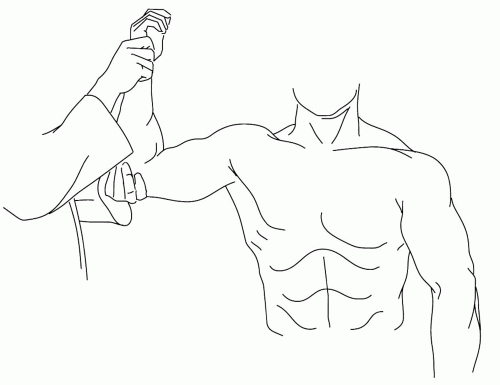

Most typically, there is no overt inflammation anywhere in the pectoral girdle, just impressive and often focal tenderness, typically deep to the belly of the deltoid. Many will experience increased discomfort in abduction, particularly in abduction with external rotation (Fig. 7.3). The last posture applies pressure to many of the subdeltoid structures by virtue of impingement on the acromion, a fact that causes some to label the periarthritis an “impingement syndrome.” However, it is not

clear from existing data that further definition of the pathophysiology is possible regardless of one’s diagnostic inventiveness, including imaging techniques. Systematic attempts at clustering patients with regional shoulder disorders by any clinical criteria led to the realization that there is very little in the history or physical examination that reliably clusters into one or more syndromes.4 That observation in general practice, coupled with an analysis that demonstrates marginal interobserver agreement,5 means the most tenable bedside diagnosis for “shoulder pain” is “shoulder pain,” perhaps with modifiers as to duration.

clear from existing data that further definition of the pathophysiology is possible regardless of one’s diagnostic inventiveness, including imaging techniques. Systematic attempts at clustering patients with regional shoulder disorders by any clinical criteria led to the realization that there is very little in the history or physical examination that reliably clusters into one or more syndromes.4 That observation in general practice, coupled with an analysis that demonstrates marginal interobserver agreement,5 means the most tenable bedside diagnosis for “shoulder pain” is “shoulder pain,” perhaps with modifiers as to duration.

Defining underlying pathoanatomy offers little illumination. As was true for the axial skeleton, degenerative changes about the joint are common regardless of symptoms. For example, degenerative changes in the rotator cuff manifest because dystrophic calcification affects more than 10% of us by the sixth decade.6 The changes are often bilateral and highly discordant from symptoms. Dissolution of the rotator cuff, with or without radiologically discernible calcification, has age-dependent prevalence becoming ubiquitous in later decades. Greater tuberosity changes revealed by radiography are also entirely nonspecific.7 Abnormalities in tendon hydration, subperiosteal cysts and irregularities, and periarticular calcification are comparably nonspecific. There exists a venerable, but anecdotal orthopedic literature on diseases of the bicipital tendon presenting as periarthritis. However, there are no data to establish the reliability, sensitivity, or specificity of the putative hallmarks of “bicipital tendonitis,” including such signs as tenderness in the bicipital groove and Yergason’s sign (pain in the shoulder when the forearm is supinated against resistance with the elbow flexed, thereby stressing the long head of the biceps and its tendon).

Given the state of the art, “shoulder periarthritis” is sufficient as a clinical diagnosis. It subsumes the labels collected over the decades attempting to ascribe the periarthritis to particular structures.

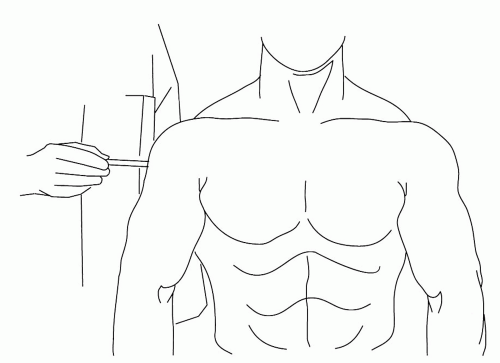

Approximately 10% of us will experience a prolonged and memorable episode of periarthritis each year. A much smaller percentage will seek medical advice. Shoulder periarthritis is always a self-limited disease; there is no evidence that these patients are at risk of a “frozen shoulder” (Chapter 9). For nearly all patients, the time to remission in terms of pain and range of motion is measurable in weeks.8 One clinical trial supported the use of some forms of physical therapy, a steroid injection into the region of the subdeltoid bursa (Fig. 7.4) or the administration of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, in shortening the time to remission.9 There are two other studies that suggested a steroid injection into the most tender spot in the deltoid helps if the onset of shoulder pain is acute. Unfortunately, most studies of interventions for shoulder periarthritis lack sufficient quality to inform practice.10 Inventiveness is not lacking. Attempting to dissolve the calcific (hydroxyapatite) deposits by driving acetic acid through the skin with iontophoresis proved disappointing.11 There is some enthusiasm for therapeutic ultrasound for calcific tendonitis,12 and one randomized clinical trial13 reported that 19% of the ultrasound-treated patients and none of the sham-treated patients had resolution of their shoulder pain after therapy. However, there is little definition of the subset of patients who were afforded such benefit. There was also a randomized clinical trial

of extracorporeal shock-wave therapy that recruited patients with more than >6 months of symptoms who had calcific deposits but no rotator cuff tear.14 At 6 months, those patients who received high-energy treatment experienced modest benefit. My concerns about this trial relate to the fact that the treatment is often so painful that intravenous analgesia is required ad hoc, thereby compromising the blinding of the trial. I will await confirmation before advocating this procedure. Surgical intervention for periarthritis is supported only by the zeal of the surgeon, whose arguments are even more tenuous than those of the ultrasonographer.

of extracorporeal shock-wave therapy that recruited patients with more than >6 months of symptoms who had calcific deposits but no rotator cuff tear.14 At 6 months, those patients who received high-energy treatment experienced modest benefit. My concerns about this trial relate to the fact that the treatment is often so painful that intravenous analgesia is required ad hoc, thereby compromising the blinding of the trial. I will await confirmation before advocating this procedure. Surgical intervention for periarthritis is supported only by the zeal of the surgeon, whose arguments are even more tenuous than those of the ultrasonographer.

It is interesting that formal rehabilitation protocols call for progressive exercising, as tolerated, of the shoulder afflicted with periarthritis.15 It follows that proscribing usage makes little sense. Rather, the treating physician should provide insights about circumventing the arcs and usages that are likely to provoke increased pain.

ELBOW PAIN

“Tennis elbow,” “student’s elbow,” “golfer’s elbow,” and “writer’s cramp” are as much a part of parlance as “to bend an elbow” or “elbow your way.” It is remarkable

how willing we are to infer that the most significant disability we experience as a consequence of our regional elbow pain is the clue to its pathogenesis. We do not call angina “stair climber’s chest,” do we? In fact, some 15% of us can recall a week of elbow pain or recurring elbow pain last year whether or not we are employed in tasks demanding of elbow function. Some 1% to 3% of the adult population will carry the diagnosis of “epicondylitis” at some point during their lives, usually between ages 40 and 60 years. People with lateral epicondylitis have difficulty hitting a tennis ball with a topspin backhand, but we have no clue as to why they have lateral epicondylitis in the first place. In fact, it has been difficult to establish an association with activities that involve repetitive motions or only modest physical demands whether the pain is at the lateral16 or medial17 elbow. Furthermore, the risk of having elbow pain, and for prolongation of pain, is increased for individuals who perceive their upper-extremity avocational or vocational activities to involve greater physical demands18; their risk is also increased for concomitant regional musculoskeletal disorders. In Section III we will consider whether the physical demands are the sole or even the predominant reason for the increased incidence, likelihood of concomitant symptoms, and prolonged course. For example, in female employees, the association with low social support is more impressive and consistent than the association with precise, demanding movements or use of handheld vibrating tools.19

how willing we are to infer that the most significant disability we experience as a consequence of our regional elbow pain is the clue to its pathogenesis. We do not call angina “stair climber’s chest,” do we? In fact, some 15% of us can recall a week of elbow pain or recurring elbow pain last year whether or not we are employed in tasks demanding of elbow function. Some 1% to 3% of the adult population will carry the diagnosis of “epicondylitis” at some point during their lives, usually between ages 40 and 60 years. People with lateral epicondylitis have difficulty hitting a tennis ball with a topspin backhand, but we have no clue as to why they have lateral epicondylitis in the first place. In fact, it has been difficult to establish an association with activities that involve repetitive motions or only modest physical demands whether the pain is at the lateral16 or medial17 elbow. Furthermore, the risk of having elbow pain, and for prolongation of pain, is increased for individuals who perceive their upper-extremity avocational or vocational activities to involve greater physical demands18; their risk is also increased for concomitant regional musculoskeletal disorders. In Section III we will consider whether the physical demands are the sole or even the predominant reason for the increased incidence, likelihood of concomitant symptoms, and prolonged course. For example, in female employees, the association with low social support is more impressive and consistent than the association with precise, demanding movements or use of handheld vibrating tools.19

The elbow is an elegant hinge joint. For nearly all regional musculoskeletal diseases of the elbow, passive motion in flexion/extension and supination/pronation is pain-free and unimpaired. The exception is osteoarthritis of the elbow, which can interfere with motion, particularly radiohumeral motion resulting in a flexion contracture. Osteoarthritis of the elbow is usually seen in the settings of calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease as a consequence of overt trauma (secondary osteoarthritis) or exceptional arm usage such as that of baseball pitchers. “Primary” osteoarthritis has been described in middle-aged men and is often associated with osteoarthritis of the second and third metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints, but it is rare.20 Therefore, if radiohumeral or radioulnar motion is impeded or painful, intraarticular inflammation is the diagnosis to be excluded; the spectrum of causes shifts to include the inflammatory arthritides, infectious arthritis, and a hemarthrosis as a consequence of impact on the hand with an outstretched arm. Arthrocentesis is necessary to make a definitive diagnosis.

The regional diseases are periarticular, involving the structures around the epicondyles or the olecranon bursa. Disorders of the olecranon bursa are sufficiently distinctive in presentation and pathogenesis to merit a distinctive classification. However, tenderness in the region of the epicondyles is not any more valid an indicator of the underlying pathophysiology than tenderness about the shoulder in the case of shoulder periarthritis. Biopsies of the sore tissue near the epicondyles always reveal little more than subtleties that may be coincidental or even age-dependent normal changes. There may be exceptional patients with inflamed, swollen tissue demonstrable by magnetic resonance imaging or sophisticated forms of sonography,21 but these patients are far more exceptional than one would presume by reading the literature. A systematic review of the imaging literature demonstrated

its serious methodologic shortcomings.22 There are changes to be seen, but these changes are more frequent as we age and often present in the asymptomatic arm. Most of the published imaging studies are so inadequately controlled or otherwise flawed as to be uninterpretable or unconvincing. The state of the art is that terms such as “epicondylitis” and “tendonitis” should denote nothing more than discrete anatomic sites of tenderness and use-related discomfort. Others who decry the current nosology suggest substituting a term such as “tendinopathy,”23 in which the suffix denotes little more than something is wrong. I am happy to say that something is wrong as long as it is not terribly wrong, not permanent, and not destructive. The term “epicondylitis” should be relegated to the archives. We might substitute “elbow periarthritis,” paralleling “shoulder periarthritis,” but that gives me pause. In both instances, the only evidence of the inflammation that the “-itis” suffix connotes is the pain; seldom is there a specific finding on examination or biopsy or by any imaging modality. Clearly this is a painful condition that must have a molecular basis, but the state of the science suggests the best term would be something such as “shoulder or elbow painfulness.” The Swedes compromise with the term “epicondylalgia”; the suffix “-algia” connotes pain only. I could countenance periarthralgia, but for the sake of communicating, I favor calling regional elbow pain, “elbow pain,” perhaps lateral or medial elbow pain.

its serious methodologic shortcomings.22 There are changes to be seen, but these changes are more frequent as we age and often present in the asymptomatic arm. Most of the published imaging studies are so inadequately controlled or otherwise flawed as to be uninterpretable or unconvincing. The state of the art is that terms such as “epicondylitis” and “tendonitis” should denote nothing more than discrete anatomic sites of tenderness and use-related discomfort. Others who decry the current nosology suggest substituting a term such as “tendinopathy,”23 in which the suffix denotes little more than something is wrong. I am happy to say that something is wrong as long as it is not terribly wrong, not permanent, and not destructive. The term “epicondylitis” should be relegated to the archives. We might substitute “elbow periarthritis,” paralleling “shoulder periarthritis,” but that gives me pause. In both instances, the only evidence of the inflammation that the “-itis” suffix connotes is the pain; seldom is there a specific finding on examination or biopsy or by any imaging modality. Clearly this is a painful condition that must have a molecular basis, but the state of the science suggests the best term would be something such as “shoulder or elbow painfulness.” The Swedes compromise with the term “epicondylalgia”; the suffix “-algia” connotes pain only. I could countenance periarthralgia, but for the sake of communicating, I favor calling regional elbow pain, “elbow pain,” perhaps lateral or medial elbow pain.

Regional Elbow Pain

Regional elbow pain is important. The diagnosis can be made on the basis of the quality of the pain, its localization, and the fact that the pain is exacerbated by particular motions, although the physical signs are of limited reproducibility.24 In most instances, the patient localizes the pain to a side of the elbow. In most instances, that side is tender without other signs of inflammation. More specific signs involve the elicitation of discomfort when the muscle mass inserting into the epicondyle is contracted against resistance. Supination of the forearm or extension of the pronated wrist against resistance elicits pain in the region of the lateral epicondyle in the case of lateral elbow periarthralgia. Flexion of the supinated wrist against resistance elicits pain about the medial epicondyle in the case of medial elbow periarthralgia. In the case of regional pain localizing near the lateral epicondyle, there is some discussion (see Chapter 9) about whether entrapment of the radial nerve in the “radial tunnel” can present in this fashion, but the arguments are not compelling.

These signs are diagnostic and generate advice that can be impressively palliative. If these motions are avoided, discomfort is diminished while awaiting the likelihood of spontaneous regression of the condition. It can take weeks or months before full activities can be resumed without recrudescence, but there are few among us for whom such patience is impractical. After all, most tasks can be adjusted or accomplished in alternative fashion to avoid these particular usages. For those who cannot, such as a tennis player with periarthritis localizing laterally, either another avocation should be pursued for several months or the patient can “run around the backhand.” This approach is the most sensible, requiring no more than patience and maturity.

Unfortunately, there is a contract between medicine and American society that thwarts “patience and maturity” and predisposes one to choose unproved remedies despite incurring discomfort, risk, and expense. Progressive, structured exercising is often advised in America, whereas it is proscribed in Britain. Zeal for antiinflammatory drugs, intralesional injections, orthotics, and the last resort of surgery all have primacy in the American mind. Double-blind comparisons of intralesional corticosteroid preparations with local anesthetic25 or non-invasive modalities should relegate intralesional steroids to the archives.26 I no longer offer intralesional steroid injection as a therapeutic alternative. In fact, the science supports reassurance, biomechanical advice, and patience as optimal therapy27 in the long run with perhaps the addition of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.28 As was the case for shoulder periarthralgia, there is much inventiveness regarding treating elbow pain. Three attempts to demonstrate benefit from various doses of extracorporeal shock-wave therapy were published in 2002; they were all disappointing.29, 30, 31 As for surgery, I remain appalled by the lack of systematic studies. The principle underlying surgery makes no sense to me; why should the scar that forms after incising and reinserting the enthesis at the epicondyle be assumed to heal better than the periarthritis itself over a comparable period of time?

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree