Upper Extremity Considerations: Hand, Wrist, and Elbow

Roderick J. Bruno

Jason M. McKean

Steven H. Goldberg

Robert J. Strauch

Melvin P. Rosenwasser

It has been estimated that by the year 2020, 18.2% or 59.4 million Americans will be affected by osteoarthritis (OA).1 The causes of OA are multifactorial,2 and in the upper extremity, the majority of cases result from a post-traumatic or idiopathic etiology. The prevalence of OA in the hand has been shown to increase with advancing age and at a higher rate in women, especially in patients older than 50 years.3 Radiographic evaluation of the hand confirms a higher incidence of OA in women, but the joints most frequently affected are the same in both sexes.4 The distal interphalangeal, thumb carpometacarpal (CMC), proximal interphalangeal, and metacarpophalangeal joints are most frequently affected in that order.4 A study has reported an association of obesity with the development of OA in the hand.5 Appearance of OA at an earlier age (younger than 50 years) may be indicative of a familial or genetic predisposition.6 Autosomal dominant transmission7 has been described for hereditary arthritic changes of OA. Recent studies have revealed a genetic component that can also be transmitted in a nonmendelian manner. Some investigators have shown joint-specific genetic susceptibility in hand OA.8,9 The products of genes that play a role in the regulation of chondrocyte differentiation and survival have been implicated in OA susceptibility, including interleukin 1 (IL1), IL-4 receptor alpha-chain, frizzle-related protein 3 gene (FRZB), and the asporin gene (ASPN).10,11,12

The goals of treatment of OA in any joint must include the relief of pain, suppression of inflammation, maintenance of function, and prevention of deformities.13 Activity modification, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications, analgesics,14 and occupational therapy are the most commonly used nonsurgical modalities for the management of upper extremity OA.15 Because acetaminophen has been shown to be effective in many patients with mild to moderate pain and has minimal side effects when appropriately prescribed in patients without hepatic dysfunction, it is often the first-line drug of choice.16 In patients with more severe pain or in the presence of inflammation, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents may be more effective and merit consideration for initial therapy or use in combination with acetaminophen.17 The role of antibiotics in OA is also being examined. A study demonstrated that oral administration of doxycycline inhibited collagenase and gelatinase activity in human cartilage with preexisting OA.18 In addition to oral administration of drugs, topical or intra-articular corticosteroids can provide pain relief. Intra-articular corticosteroid injections into the thumb basal joint have shown to be well tolerated and reduce pain,19 but significant long-term benefits have only been shown in early arthritis.20,21 Hand therapy encompasses activity modification, splinting, and modalities including hot soaks, paraffin baths, and strengthening exercises. By providing local pain relief and alternately resting and using the joints, joint function can be preserved.

There has been recent interest in alternative treatments of OA, such as use of nutraceuticals.22,23,24,25 Short-term trials have demonstrated benefits in the treatment of OA with glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate.26,27 However, studies using meta-analysis of the available data have stated that definitive evaluation is not possible.24,25,28,29 The source of the glucosamine may have an effect on its efficacy.30 Because these compounds are not considered drugs, they

are not subjected to the same rigorous safety and efficacy testing by the Federal Drug Administration as other medications. Therefore, the specific components of a preparation may vary considerably, leading to variable degrees of efficacy and safety. Glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate may play some role in the moderation of symptoms in OA, but their effects are modest in most populations of patients.

are not subjected to the same rigorous safety and efficacy testing by the Federal Drug Administration as other medications. Therefore, the specific components of a preparation may vary considerably, leading to variable degrees of efficacy and safety. Glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate may play some role in the moderation of symptoms in OA, but their effects are modest in most populations of patients.

Distal Interphalangeal Joint

Degenerative OA of the distal interphalangeal joint is most commonly seen in men and women older than 40.31 Arthritis of this joint presenting at an earlier age has been recognized to have an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern.32 Isolated trauma, such as chronic untreated mallet finger, may mimic degenerative OA in the distal interphalangeal joint.

Early radiographic evidence of OA is joint space narrowing secondary to thinning of articular cartilage. Bone spur formation with erosion and joint obliquity may cause malalignment and instability of the distal phalanx. As the disease progresses, the base of the phalanx may broaden, and cysts may form. Hypertrophy of capsular and ligamentous structures contribute to the bulbous appearance of the joint.

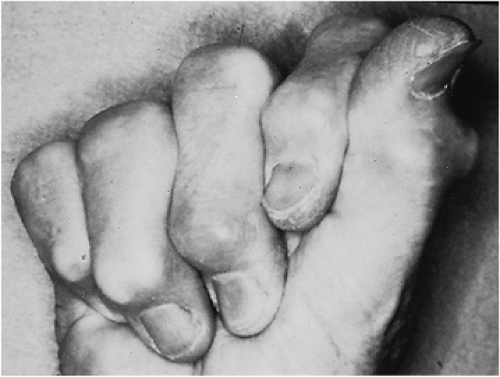

The Heberden node, a prominent and often painful exostosis, is characterized by osteophyte formation on the dorsal and lateral aspects of the distal finger joint (Fig. 20B-1). Heberden nodes, which are typically large and painless after their initial emergence, cause a cosmetic deformity with the joint fixed in a slightly flexed position. This results in attenuation of the terminal extensor tendon by osteophytes, creating an apparent pseudo-mallet finger deformity with an extensor lag.

Surgical treatment options include arthrodesis, cheilectomy, and arthroplasty. Arthrodesis achieves a stable joint, free of pain and deformity, but sacrifices function (Fig. 20B-2). Provided that the proximal interphalangeal and metacarpophalangeal joints in the finger are supple and relatively asymptomatic, arthrodesis of the distal interphalangeal joint has only small effects on grip and pinch activities. At the distal interphalangeal joint, full extension is the most common position of fusion, although slight flexion for the border digits is acceptable. A multitude of fusion techniques have been advocated.33,34,35 Complications from distal interphalangeal joint arthrodesis have been reported to be as high as 30% and are mainly nonunion and malunion.36,37

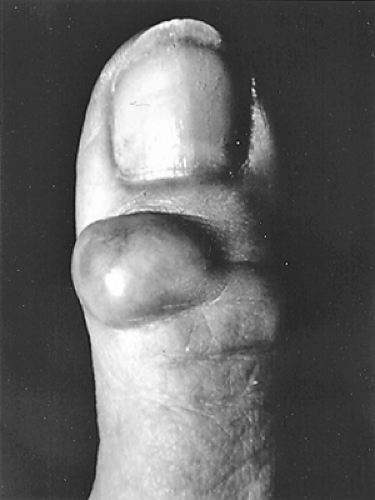

Cheilectomy with removal of excessive bone is an alternative to fusion. Cheilectomy can improve joint motion in certain cases but more reliably serves to improve cosmesis. It is routinely performed as part of the treatment of mucous cysts which are ganglion-like masses that arise most commonly from the distal interphalangeal joint (Fig. 20B-3). They are associated with underlying osteophytes. The cyst may rupture through the overlying skin as it enlarges and may lead to septic arthritis. Excision of the cysts is recommended when the patient has pain or when skin compromise has occurred. Recurrence rates of up to 50% have been reported, especially if the underlying osteophytes are not removed.38 In fact, mucous cyst and underlying osteophyte removal is one of the most commonly performed surgical treatments for distal interphalangeal joint arthritis. Specific technical portions of the procedure include elevating the proper collateral ligaments from their attachments as a sleeve from the distal phalanx joint to prevent iatrogenic instability. The osteophytes are débrided on either side of the extensor tendon. The extensor tendon should not be disturbed or split longitudinally to facilitate bone removal or the tendon will attenuate, resulting in an irreparable mallet finger.

Because arthrodesis of the distal interphalangeal joint is well tolerated, implant arthroplasty is rarely performed. Success has been reported in long-term follow-up studies of silicone arthroplasty; an average of 33° of range of motion is preserved at 6- and 10-year follow-up, with a 10% implant removal rate in one study.39,40

Proximal Interphalangeal Joint

Proximal interphalangeal joint primary OA, so-called Bouchard nodes, is pathoanatomically similar to distal interphalangeal joint OA but occurs with much less frequency. OA of this joint displays familial tendency and is more common in women and with aging beyond 50 years. Mucous cysts are less commonly associated with OA in the proximal interphalangeal joint than in the distal interphalangeal joint. Patients present clinically with swelling, loss of motion, and characteristically little pain. Swan-neck or boutonniere deformities with tendon imbalance such as that seen in rheumatoid arthritis are unusual.41

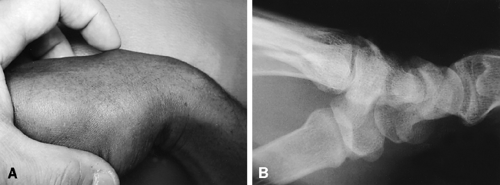

Radiographic evidence supports the tenet of mirror OA lesions across similar joints in the hand4,42 (Fig. 20B-4). Isolated arthritis of one proximal interphalangeal joint suggests an etiology other than idiopathic arthritis. However, early in the course of the disease process, one-joint involvement may be a sentinel of developing OA. Post-traumatic arthritis in this joint is often secondary to intra-articular fracture or fracture-dislocations resulting in chronic joint

subluxation or dislocation that causes cartilage degeneration. Conservative treatments including heat modalities, mild analgesics, and activity modification may palliate the early stages of the disease. Advanced disease, especially with pain and stiffness, may need surgery, including cheilectomy, arthroplasty, and arthrodesis. Large lateral osteophytes may displace the lateral bands, precluding tight fist closure of the hand. Volar osteophytes may also contribute to the loss of flexion motion. Cheilectomy offers a temporizing procedure to improve joint mechanics. Osteophyte excision is usually through a palmar incision, with release of the volar plate and resection of the accessory collateral ligaments. Palmar plate resection arthroplasty, when combined with flexor tenodesis, can provide a stable joint with preserved motion43 and a range of motion from 5° to 95° in 87% of patients with a 94% satisfaction rating by patients.44

subluxation or dislocation that causes cartilage degeneration. Conservative treatments including heat modalities, mild analgesics, and activity modification may palliate the early stages of the disease. Advanced disease, especially with pain and stiffness, may need surgery, including cheilectomy, arthroplasty, and arthrodesis. Large lateral osteophytes may displace the lateral bands, precluding tight fist closure of the hand. Volar osteophytes may also contribute to the loss of flexion motion. Cheilectomy offers a temporizing procedure to improve joint mechanics. Osteophyte excision is usually through a palmar incision, with release of the volar plate and resection of the accessory collateral ligaments. Palmar plate resection arthroplasty, when combined with flexor tenodesis, can provide a stable joint with preserved motion43 and a range of motion from 5° to 95° in 87% of patients with a 94% satisfaction rating by patients.44

Figure 20B-4 Anteroposterior radiograph of the hand demonstrating proximal interphalangeal joint OA. |

As with the distal interphalangeal joint, arthrodesis of the proximal interphalangeal joint provides a pain-free, stable joint. Arthrodesis is the preferred method of treatment of any digit that presents with instability, but it is used primarily in the radial digits, particularly the index finger, because it provides additional stability for pinch.45 In a review of a variety of fusion techniques, including Herbert screws, Kirschner wires, tension band wiring, and plating, Leibovic and Strickland46 reported that Herbert screw fixation had the most predictable outcome. Tension band wiring is preferred by others,47 with fusion rates from 86% to 97%.46,47 Fusion angle is variably based on the natural cascade of flexion from radial to ulnar: 25° to 30° for the index finger, 30° to 35° for the long finger, 35° to 40° for the ring finger, and 40° to 45° for the small finger.

Arthroplasty of the proximal interphalangeal joint is best reserved for the central digits (long and ring), which are protected from shear and angular stress by the adjacent digits. Implant material and durability limit indications in manual laborers with high physical demands. Implants are constructed out of various materials including silicone, titanium, pyrolytic carbon, or combinations of materials. The most commonly implanted material is silicone. The implants may be secured by press-fit, cement, or they may be allowed to piston within the bone. In most studies, regardless of the type of implant, pain is relieved, but range of motion is unchanged.48 However, each implant has different complications and modes of failure. Silicone implants are associated with implant fracture, bone resorption, and instability.45,49 Cemented, hinged biomeric devices had well-fixed stems, but had an early failure rate at an average of 2.25 years due to symptomatic device failure at the elastomer hinge leading to prosthesis dissociation, particulate debris, joint instability, and angular deviation of the finger.45 Early studies using osseointegrated prostheses50 and surface-replacing arthroplasties51 are promising, but long-term results are not available. In a retrospective study involving 18 proximal interphalangeal joint arthroplasties in 8 women using pyrolytic carbon implants, range of motion decreased in half the patients and satisfaction was only 50%.52 Another study that included 25 joints in 19 patients investigated the use of titanium implants with silicone spacers.53 While there was adequate osteointegration into 94% of the titanium implants, there was a 68% fracture rate of the silicone spacers. Despite the fracture rate, 80% of the patients were satisfied with pain

relief. There is no single current arthroplasty design or material that is superior. Whereas objective parameters of success of arthroplasty may not be evident, patient-based subjective satisfaction, particularly with pain relief, remains high and may be the primary benefit of this procedure.54

relief. There is no single current arthroplasty design or material that is superior. Whereas objective parameters of success of arthroplasty may not be evident, patient-based subjective satisfaction, particularly with pain relief, remains high and may be the primary benefit of this procedure.54

Metacarpophalangeal Joint

Primary OA of the metacarpophalangeal joint is rare, and an underlying cause should be investigated, particularly a history of trauma or an underlying systemic disease.55 There is likely a genetic predisposition to metacarpophalangeal joint OA, and mutations in the HFE gene have been shown to be associated with OA of the index and middle metacarpophalangeal joints.56 The loosely constrained cam configuration of the metacarpophalangeal joint allows abduction-adduction in addition to flexion-extension. Restoration of mobility is the treatment goal for OA of this joint. Grasp is greatly affected by loss of active flexion, particularly when only one of the metacarpophalangeal joints is affected. Post-traumatic ligamentous injuries may lead to joint instability and subsequent cartilaginous injury. Impaction injuries to the cartilage can occur with activities such as boxing and the martial arts. Intra-articular fractures, fracture-dislocations, and osteonecrosis after fracture have been implicated in the cause of secondary OA in the joint.57 The risk of post-traumatic OA of the metacarpophalangeal joint can be minimized if displaced intra-articular fractures are stabilized and early motion is allowed.58

Unlike the distal interphalangeal joint, metacarpophalangeal joint arthrodesis results in significant loss of function. Therefore, treatment of this joint focuses on maintenance of range of motion with some type of arthroplasty. When the joint articular surface is severely damaged, one surgical option is interposition palmar plate arthroplasty. For post-traumatic or postseptic OA, palmar plate arthroplasty has been shown to provide a stable, pain-free joint up to 4 years postoperatively, with a joint flexion arc of 55°.59 If the volar plate arthroplasty fails, implant arthroplasty can still be performed.

Most of the literature on arthroplasty for the metacarpophalangeal joint has been written in regard to rheumatoid arthritis. However, silicone arthroplasty for degenerative arthritis has also proved successful. Modifications to enhance the durability of these flexible implants, including the use of grommets, are controversial.60,61 The surgical technique described by Swanson62 emphasizes soft tissue rebalancing as integral to the success of the hinged implant. Active motion within a few days of surgery, as dictated by skin healing, combined with dynamic splinting, has achieved good results.63

The Swanson silicone implant with or without grommets is the most widely used implant for metacarpophalangeal joint replacement and is the preferred implant of the authors.64,65 However, newer designs with more anatomic features have been introduced and show promise. In a study of joint mechanics of three silicone implants, the NeuFlex (DePuy Orthopaedics, Warsaw, IN) implant appears to more closely reproduce joint motions than the other two implants.66 There was no statistically significant difference between the kinematics of the metacarpophalangeal joints with the preflexed implant and the joints that were not operated on.67 Unconstrained pyrolytic carbon metacarpophalangeal joint implants have shown excellent long-term results without the need for revision or significant particulate debris.68 Implant stem stabilization by osseointegration is being evaluated,69 but the long-term efficacy of these devices is unproven.

Fusion of the metacarpophalangeal joint at any angle of flexion causes a loss of hand function but may still be indicated, particularly for an unstable index or middle metacarpophalangeal joints. Fusion is a last resort, but when it is required (under such conditions as massive bone loss after infection, mutilating injury, or failed implant arthroplasty), the position of fusion should follow the resting posture of the flexed hand, with the index finger in 20°, the long finger in 25°, the ring finger in 30°, and the small finger in 35° of flexion.

Degenerative changes in the thumb metacarpophalangeal joint are more common and may be seen after high-grade injuries with disruption of the ulnar or radial collateral ligaments. Collateral ligament injury can lead to subluxation of the joint and to changes in normal contact forces, which lead to cartilaginous wear. Late repair of the ulnar or radial collateral ligaments of the thumb metacarpophalangeal joint has been successful in restoring normal joint mechanics and should be considered unless the articular cartilage wear is severe. Secondary arthritis of the thumb metacarpophalangeal joint may also result from chronic hyperextension in a patient with motion-limiting thumb basilar joint arthritis. Thumb metacarpophalangeal joint fusion will predictably result in excellent function with power grasp and pinch as long as there is preservation of CMC motion. However, concomitant OA at the CMC joint would need to be addressed simultaneously with any metacarpophalangeal arthrodesis in order to fully address the arthritis of the entire ray and achieve long-term pain relief and function. Fusion of the thumb metacarpophalangeal joint in 10° of flexion is recommended for painful instability.

Carpometacarpal Joints

Sometimes less-invasive measures, such as injections, can be effective in pain control with CMC joint OA. Local corticosteroid injection can be done safely in an office setting based on anatomical landmarks70 and may alleviate symptoms.

Carpal bossing of the second or third CMC joint may occur in conjunction with or may be misdiagnosed as an isolated dorsal ganglion (Fig. 20B-5). This often results from subacute trauma such as extreme radial or ulnar deviation forces, as in taking a divot with a golf swing. The bone prominence of the carpal boss with associated soft tissue hypertrophy may be painful. Osteophytes may irritate the overlying extensor tendons; however, simple cheilectomy may not provide lasting relief. Early studies reported that simple excision of osteophyte and degenerative tissue provided symptomatic relief.71,72 A later study demonstrated a 77% failure of boss excision or arthrodesis to relieve symptoms, contrasting with previously reported findings.73

Cadaveric analysis has shown that dorsal wedge excision approximately doubles the passive range of motion of the CMC joint, disturbing the normal anatomy and creating instability.74 For the rare symptomatic carpal boss, excision with CMC fusion is recommended.

Cadaveric analysis has shown that dorsal wedge excision approximately doubles the passive range of motion of the CMC joint, disturbing the normal anatomy and creating instability.74 For the rare symptomatic carpal boss, excision with CMC fusion is recommended.

Thumb Carpometacarpal Joint

OA of the thumb CMC joint is a common and debilitating condition second in incidence only to distal interphalangeal joint arthritis.31 Epidemiologic studies have shown an overall gender differential in prevalence, with women affected six times more frequently than men.75 However, a recent study demonstrated an elevated first CMC joint OA rate in men (9%) compared to women (5%) within the age group of 40 to 49 years of age.31 This difference may be due to anatomic variation, hormones, or other factors.76,77,78 Although an idiopathic etiology is most common, there are known genetic predispositions to thumb CMC joint OA. A relatively strong association between OA of the first CMC joint and chromosome 15 has been implicated, with candidate genes around including cartilage intermediate-layer protein (CLIP), aggrecan core protein precursor, fibrillin 1, fibroblast growth factor 7, and insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor.79

The thumb CMC joint consists of the articular surfaces of the distal trapezium and the proximal thumb metacarpal with two reciprocally opposed saddles. This unique shape in the human body allows the prehensile capability of the thumb. Passive stability is provided by the bony anatomy and six defined ligaments: the anterior oblique, palmar beak, posterior oblique, dorsoradial, ulnar collateral, and intermetacarpal ligaments. The extrinsic and intrinsic muscles of the thumb also contribute to the active stability of the CMC joint.

Unlike a ball and socket joint, the CMC joint has a certain degree of incongruity that allows its physiologic motion. The saddle shape allows flexion-extension, abduction-adduction, and axial rotation. The saddle-shaped anatomy and the kinematics of the joint are believed to be related to the pathogenesis and development of OA.80 Imaeda and colleagues81 have demonstrated that the center of rotation of the joint is not fixed; rather, it moves from the trapezium to the metacarpal as the thumb assumes flexion-extension and abduction-adduction attitudes.

The pathogenesis of OA in the thumb CMC joint is multifactorial. High focal stresses on joint cartilage may be a primary cause.82 Ligamentous laxity may play a role as well. A common deformity in advanced basal joint arthritis is dorsal subluxation and adduction of the metacarpal on the trapezium with compensatory metacarpophalangeal joint hyperextension. The primary restraint to dorsal subluxation is the dorsoradial ligament, although detachment or attenuation of the anterior oblique ligament also alters joint mechanics, may lead to arthritis.68,69,83 Because ligaments provide optimal stability at different joint positions, they all play a role in joint stabilization, and the deterioration of thumb CMC cartilage is dependent on pathologic changes in multiple ligaments.83

Changes in biochemical composition of cartilage in the CMC joint relative to baseline normal values occurs with OA and directly affects the biomechanical properties of cartilage.84 Additionally in OA, articular cartilage injury has been shown to occur in common patterns. It begins radially on the metacarpal base and dorsoradially on the trapezium then progresses palmarly in both in later stages.85 This has been demonstrated in cadavers showing regional variation in contact areas during different joint positions which are associated with regional variation in cartilage thickness.82 Thus, there are high and low load-bearing areas in positions of pinch and grasp. Pinching and gripping generate large loads across the CMC joint and contribute to the development of OA.86 Thumb adduction with tip pinch may accentuate the incongruity of the joint and promote wear. The joint reactive force may be ten times the tip pinch force of the thumb and can exceed 1500 Newtons during strong grasp.

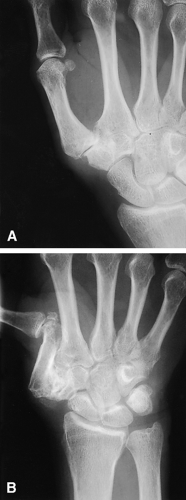

Radiographs are the most common and useful initial diagnostic study to evaluate the thumb CMC joint for OA. Pronated anteroposterior, lateral, and oblique views centered over the trapezium are routinely obtained. It is often useful to image both hands on the same film to assess for symmetry. The Eaton classification is based on the degree of degenerative changes noted on the radiograph and the presence or absence of scaphotrapezial arthritis.87 In stage 1 disease, the joint space is preserved or mildly widened, indicative of synovitis or effusion. Stage 2 involves joint space narrowing with subchondral changes and osteophytes smaller than 2 mm (Fig. 20B-6A). In stage 3, there are more advanced degenerative changes with osteophytes larger than 2 mm. Stage 4 represents advanced joint destruction with involvement of the scaphotrapezial joint (Fig. 20B-6B).

However, radiographs tend to underestimate the severity of the disease both at the trapeziometacarpal joint and especially at the scaphotrapezial joint.88 A full thickness cartilage erosion in one area of the joint may not be appreciated

since the intact articular cartilage can preserve the joint space width. Additionally, since the thumb CMC joint is out of plane with the hand, it is difficult to obtain reproducible positions over sequential studies. A study quantified that radiographic staging can lag behind pathologic staging by more than one stage.89 Radiographic severity has been associated with decreased grip and pinch strength.90

since the intact articular cartilage can preserve the joint space width. Additionally, since the thumb CMC joint is out of plane with the hand, it is difficult to obtain reproducible positions over sequential studies. A study quantified that radiographic staging can lag behind pathologic staging by more than one stage.89 Radiographic severity has been associated with decreased grip and pinch strength.90

Symptomatic thumb CMC arthritis usually presents with dorsal and palmar basal joint pain at the thenar eminence, exacerbated by tip pinch and grasp. Deformity may also be present (Fig. 20B-7). Clinically advanced OA demonstrates the “shoulder sign” with dorsoradial subluxation of the first metacarpal on the trapezium. Pain can be elicited by palpation of the dorsal radial aspect of the trapeziometacarpal joint, adduction of the thumb, or with rotation of the axially loaded joint (grind test).

Compensatory deformities, such as collapse of the thumb-index web space with hyperextension of the metacarpophalangeal joint, should be noted because they will affect the treatment plan. Confounding diagnoses such as de Quervain tenosynovitis, carpal tunnel syndrome, and radioscaphoid arthritis must be ruled out.

Initial treatment is focused on rest, limited immobilization, behavior modification, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medicines. Several randomized, prospective studies demonstrate the efficacy of nonoperative treatment for early, mild basal joint arthritis. Seventy percent of patients in a group that was waiting for basal joint arthroplasty never underwent surgery during a 7-year study period when they were treated with occupational therapy, splinting, technical accessories, and advice on how to improve function through activity modification.91 Other studies have shown that soft splints made of prefabricated neoprene, for example, are better tolerated with equal efficacy with respect to pain relief than more rigid splints, even when custom made.67,92

Intra-articular steroid efficacy has been shown to be inversely related to stage of disease. Splinting and steroid injection are superior to either alone; they are more effective and last longer in milder stages of OA. This was confirmed in a randomized, double-blind study comparing corticosteroid and saline in patients with moderate to severe CMC joint OA in which no difference in pain relief was observed.21 Pain relief with intra-articular steroids may be delayed several weeks.19,20,21,22 The major disadvantages of frequent steroid injections are possible injection site depigmentation and degradation of articular cartilage or the joint capsule.93 Intra-articular hyaluronic acid also provides equivalent pain relief as steroids within 1 month of injection and improved strength and function from 3 to 6 months.94 Another randomized, blinded controlled trial that the senior authors recently submitted for publication showed injections of hylan provided greater pain relief based on visual analog scores than both saline and steroid injections after 27 months.

The above nonoperative measures are usually used for at least a 3-month trial in an attempt to minimize pain and avoid contractures; however, response is variable and may be related to the patient’s workload, activity level, and extent of arthritis.95 Failure to control pain or inability or unwillingness to accept activity limitations are major indications for surgical treatment. Constitutional or acquired ligamentous laxity also affects the success of nonoperative and operative treatments. Most patients who elect surgery are in the advanced stages of OA. A host of surgical alternatives have been described, including arthrodesis, osteotomy, resection arthroplasty, ligament reconstruction with or without tendon interposition, and prosthetic replacement. Most techniques report good to excellent pain relief with a wide range of recovery of strength and functional capacity.

For early basilar thumb joint disease with instability but preservation of cartilage, Eaton has reported good results with an extra-articular ligament reconstruction using the flexor carpi radialis tendon.69 Ligament reconstruction has been shown to preserve function and retard progression of OA.96 Metacarpal extension osteotomy can also be performed in early disease.97 Cadaver studies have shown metacarpal osteotomy shifts contact forces in the joint, which may unload and alleviate symptoms of arthritis; compared to ligament reconstruction, osteotomy may more comprehensively reduce thumb laxity.98,99 Finally, arthroscopic procedures have also been described for early

arthritis. These include debridement, thermal capsular shrinkage, interpositional arthroplasty, and hemitrapeziectomy or complete trapeziectomy.100,101,102,103,104 No prospective randomized trials have evaluated the efficacy of arthroscopic treatment, but a small series of 24 thumbs in 22 patients treated arthroscopically had successful results and 8 patients who had an open arthroplasty on the contralateral side preferred their arthroscopic procedure.105

arthritis. These include debridement, thermal capsular shrinkage, interpositional arthroplasty, and hemitrapeziectomy or complete trapeziectomy.100,101,102,103,104 No prospective randomized trials have evaluated the efficacy of arthroscopic treatment, but a small series of 24 thumbs in 22 patients treated arthroscopically had successful results and 8 patients who had an open arthroplasty on the contralateral side preferred their arthroscopic procedure.105

In more advanced basal joint arthritis, there are multiple treatment options that center around a complete trapeziectomy to remove the painful bone contact with variations in reconstruction of the ligaments and interposition of tissue into the trapezial space (Fig. 20B-8). Several randomized, prospective studies analyze various surgical treatments for basal joint arthritis. Although many of the studies are small and do not include a power analysis, the following conclusions can be reasonably drawn. Trapeziectomy is the primary critical element of surgical treatment of advanced basal joint arthritis because it removes the painful trapezial-metacarpal articulation. Trapeziectomy alone may be all that is necessary to treat basal joint arthritis since there is no difference in patient outcomes between patient groups who underwent trapeziectomy, trapeziectomy with tendon interposition, or trapeziectomy with ligament reconstruction.106,107,108,109,110 However, all five of these studies recommending trapeziectomy alone were performed by two groups and only short-term results up to 1 year have been evaluated. Thus, the outcome of trapeziectomy alone in the long-term is unknown, and isolated trapeziectomy seems to have the highest risk for progressive collapse and pain over time from metacarpal-scaphoid contact, which occurred in several patients who did not have stabilization of the thumb metacarpal with either ligament reconstruction or tendon interposition.110 Revision procedures have been described more commonly after isolated trapeziectomy for metacarpal-scaphoid arthritis,111 whereas only one metacarpal-scaphoid painful articulation has been described in the randomized, prospective studies in which ligament reconstruction was performed.112,113,114 The primary reasons to perform ligament reconstruction and/or tendon interposition is to maintain trapezial space height, thumb ray length, and to stabilize the thumb metacarpal for use during pinch. Ligament reconstruction with tendon interposition can maintain trapezial height better than ligament reconstruction alone.113 However, the maintenance of trapezial height may not correlate with pain relief, strength, or function on validated tests at one year after surgery.113 If trapeziectomy and tendon reconstruction is performed, ligament interposition could be superfluous as some studies have found that it does not improve patient outcome, requires more surgical dissection, more operative time, and may decrease range of motion.112 One study randomized patients to trapeziectomy with ligament interposition or silicone arthroplasty and concluded both procedures were equivalent in partially relieving pain at 48 months postsurgery, but prosthesis subluxation or dislocation was common.115 Length of postoperative immobilization has not been systematically studied, but one study suggests immobilization for only 1 week after surgery is all that is necessary for trapeziectomy alone.116

Both senior authors (RJS and MPR) routinely perform a complete trapezial excision for symptomatic advanced CMC arthritis. Additionally, one senior author (RJS) performs a ligament reconstruction using flexor carpi radialis secured to the metacarpal through bone suture anchors and interposition of the remaining tendon in the trapezial space,117 while the other (MPR) favors interposition of the palmaris longus with imbrication of the dorsal capsule and dynamic stabilization with advancement of the flexor carpi radialis to the abductor pollicis brevis origin. An assessment of metacarpophalangeal motion is performed intraoperatively. If significant metacarpophalangeal hyperextension is present (>10°), the metacarpophalangeal joint is temporarily stabilized with a transarticular Kirschner wire to prevent subluxation of the base of the metacarpal during postoperative rehabilitation. For metacarpophalangeal hyperextension of 10° to 30°, we perform a volar plate advancement or plication. The thumb is splinted in an abducted position for 2 to 3 weeks to protect the soft tissue repair. An active motion rehabilitation protocol with supervised occupational therapy is then initiated.

True thumb CMC joint arthroplasties with metal or polyethylene prosthetic devices or silicone spacer implants have been developed. Excellent short-term results with more rapid return to function have been reported; however, long-term complications, which include wear, bone resorption with loss of height, instability, loosening, and silicone synovitis, continue to be a problem.118,119,120 Long-term results of the de la Caffinière arthroplasty have been excellent in women older than 60 years, but higher failure rates were observed in more active individuals, including men and young women121,122,123,124 (Fig. 20B-9).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree