Unconstrained Prosthetic Arthroplasty for Glenohumeral Arthritis with an Intact or Repairable Rotator Cuff: Indications, Techniques, and Results

Luke S. Austin

Gerald R. Williams Jr.

Joseph P. Iannotti

INTRODUCTION

History

The first replacement arthroplasty of the glenohumeral joint dates to 1893 when a French surgeon, Pean, used a platinum and rubber implant to replace the proximal one-half of the humerus in a patient suffering from tuberculous arthritis of the shoulder.123 The implant required removal approximately 2 years later for persistent, uncontrollable infection. Additional materials used in replacement of the proximal humerus predating the modern era of shoulder arthroplasty included fibular autografts, resurfacing grafts of fascia lata, and ivory and acrylic prostheses.1,94,106,161

The modern era of unconstrained shoulder arthroplasty was founded in the early 1950s, when prosthesis design sought to replicate the anatomic shape of the humeral head. The specific geometries of the earliest nonconstrained components were derived from measurements taken from cadaveric humeri.110,144 In 1951, Krueger reported the implantation of the first anatomically designed humeral head prosthesis for a patient with aseptic necrosis.110 The short-term results of this single surgery demonstrated promise, with relief of pain and favorable function being achieved. At the same time, Neer, being prompted by his observation of the unsatisfactory results of conventional surgical treatments for proximal humeral fracture -dislocations, was designing his first anatomic prosthesis, which was introduced in a report in 1953.144 In 1955, Neer described the use of his second prosthesis, a redesigned vitallium humeral head replacement (Neer I prosthesis) in 12 cases, including patients with acute four-part proximal humeral fractures or proximal humeral fracture-dislocations and patients with avascular necrosis from prior fractures.139 The short-term results in which 11 of 12 patients were free from pain provided momentum, furthering the application of humeral head replacement surgery. In 1964, Neer published a follow-up report, in which the indications for the procedure expanded to include patients with degenerative arthritis of the glenohumeral joint.145 With a follow-up ranging from 2 to 11 years, results remained favorable and supported the use of a humeral head replacement for acute trauma, posttraumatic arthritis, and both inflammatory and noninflammatory degenerative arthritis.

In the early 1970s, several authors reported on the implantation of a polyethylene glenoid component for the humeral head prosthesis to articulate with and, as such,

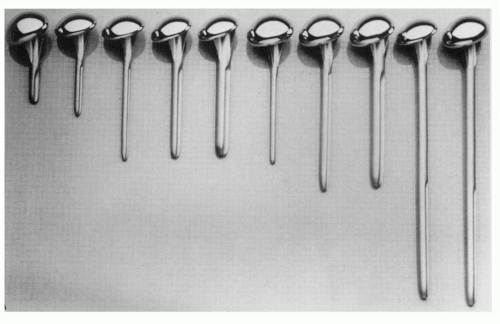

the age of total shoulder arthroplasty arrived.59,102,140,201 Neer designed a new humeral head prosthesis (Neer II prosthesis) for implantation with any of his glenoid component designs or as a humeral head replacement independent of a glenoid (Fig. 17-1). The Neer II system was the most widely used and reported nonconstrained shoulder replacement throughout the 1970s and 1980s.

the age of total shoulder arthroplasty arrived.59,102,140,201 Neer designed a new humeral head prosthesis (Neer II prosthesis) for implantation with any of his glenoid component designs or as a humeral head replacement independent of a glenoid (Fig. 17-1). The Neer II system was the most widely used and reported nonconstrained shoulder replacement throughout the 1970s and 1980s.

Poor functional results with unconstrained prosthetic implants in certain patients with rotator cuff deficiency resulted in the development of constrained and semiconstrained devices. Constrained total shoulder arthroplasty conceptionally seemed desirable because of the inherent stability achieved at the articulating surfaces and the belief that, with the maintenance of a stable fulcrum of rotation, the deltoid would be able to assume the role of the rotator cuff in a cuffdeficient shoulder. A variety of designs were introduced, most of which used a fixed fulcrum ball-and-socket type construction (Fig. 17-2). Neer and Averill designed three constrained prosthetic systems, each with a modification to improve on the previous design.146 In 1974, Neer abandoned the use of any constrained prosthesis because of dissatisfaction with mechanical failure.141 Although pain relief was satisfactory in many cases of constrained total shoulder arthroplasty, these designs lost popularity owing to relatively high rates of component mechanical failure, disassembly, and loosening at the bone- implant fixation sites.48,117,157,158

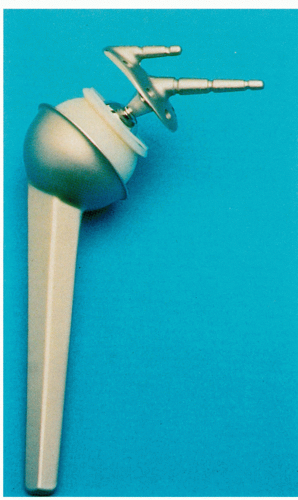

Grammont and Baulot reintroduced the concept of constrained arthroplasty in cases of irreparable rotator cuff deficiency in the early 1990s.81 Their design is a reverse ballandsocket design with a relatively large glenoid sphere with no neck (Fig. 17-3). This places the center of rotation within the glenoid vault, thereby reducing the lever arm on the glenoid anchoring point.20,81 This medialization of the center of rotation improves the deltoid moment arm and allows for improved function. Subsequent to Grammont and Baulot’s prosthesis, Frankle et al. introduced a reverse ball-and-socket design with a slightly more lateralized center.69 Early and midterm results demonstrate promising results and better survivorship than earlier constrained arthroplasties.13,14,23,69,81,93,114,163,170,190,198 It is likely that constrained reverse prostheses will continue to have a role in the management of glenohumeral arthritis with irreparable cuff deficiency. The biomechanics, indications, and results of these prostheses are discussed in more detail elsewhere in this book.

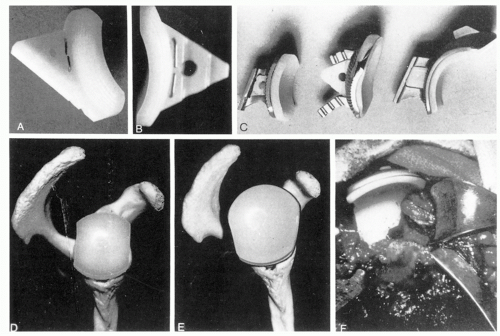

Semiconstrained glenoid components or hooded glenoid components were designed to articulate with anatomic humeral

head components for patients with rotator cuff-deficient shoulders. These glenoid components were modified with a roof-like extension or hood at the superior rim143 (Fig. 17-4). The purpose of the hooded modification was to block superior translation of the humeral head from superiorly directed displacement forces inherent to rotator cuff deficiency. In theory, the semiconstrained design should allow the deltoid to independently achieve greater degrees of arm elevation. In the few articles that report on the use of semiconstrained prostheses, improvements in active arm elevation, if they occurred at all, were not dramatic, although pain relief was satisfactory.31,57 The need for revision surgery and the number of complications were higher than in nonconstrained designs.31,57,61

head components for patients with rotator cuff-deficient shoulders. These glenoid components were modified with a roof-like extension or hood at the superior rim143 (Fig. 17-4). The purpose of the hooded modification was to block superior translation of the humeral head from superiorly directed displacement forces inherent to rotator cuff deficiency. In theory, the semiconstrained design should allow the deltoid to independently achieve greater degrees of arm elevation. In the few articles that report on the use of semiconstrained prostheses, improvements in active arm elevation, if they occurred at all, were not dramatic, although pain relief was satisfactory.31,57 The need for revision surgery and the number of complications were higher than in nonconstrained designs.31,57,61

FIGURE 17-3. The Delta (Depuy, Warsaw, IN) prosthesis, introduced by Paul Grammont, is characterized as a reverse ball-in-socket with a relatively large metal sphere with no neck. |

Nonconstrained prostheses are the devices of choice for glenohumeral replacement with an intact and functional rotator cuff. Most arthroplasty systems utilize a stemmed humeral component in conjunction with a polyethylene glenoid component. However, humeral head resurfacing without an intramedullary stem has proponents, particularly when the glenoid is not being resurfaced.2,64,119,121 Indications for glenoid resurfacing are still under question but several welldesigned studies have recently settled some of the controversy between total shoulder arthroplasty and hemiarthropla sty.12,55,122,124,127,159,178,179 Moreover, there may be a difference between hemiarthroplasties performed with stemmed implants and resurfacing arthroplasties.185

The topic of this chapter is replacement arthroplasty for conditions characterized by an intact or reparable rotator cuff. The two most representative conditions are osteoarthritis and avascular necrosis. Therefore, these two conditions will be considered most prominently. However, some cases of inflammatory (i.e., rheumatoid arthritis) and posttraumatic (i.e., arthritis of instability) arthritis fall under this category. The surgical technique is similar in these conditions and, therefore, is discussed all inclusively. Technical points germane to each individual diagnosis are inserted where appropriate.

Indications

In general, the indications for prosthetic replacement in osteoarthritis and avascular necrosis are similar to those stated for the other pathologic processes discussed in this text. Severe pain that has failed to respond to conservative measures and a degree of dysfunction that is unacceptable to the patient are the primary reasons to consider arthroplasty. The average age of patients undergoing shoulder replacement is younger than those of other major joint replacements (i.e., hip and knee). Fortunately, less weight is borne by the shoulder than hips or knees and long-term survival rates are favorable for these implants in younger patients. Bartelt et al. reported 10-year survival rates of 72% and 92% for hemiarthroplasty and total shoulder arthroplasty, respectively, in patients 55 years of age and younger.12 Furthermore, Sperling et al. reported 15-year survival rates of 73% and 84% for hemiarthroplasty and total shoulder arthroplasty, respectively, in patients 50 years and younger.178 In the past, total shoulder arthroplasty was generally reserved for patients over the age of 50, while hemiarthroplasty was considered for patients younger than 50 and older than 40. Due to the reported high rates of revision surgery following hemiarthroplasty, these general guidelines may not be entirely appropriated and consideration to other variables such as activity level, degree of glenoid wear, degree of humeral head collapse, and general medical condition must be weighed in the decision-making process.

Patients 40 years and younger, or older patients who are extremely physically active, with symptomatic glenohumeral arthritis with an intact rotator cuff requiring surgical intervention present a significant treatment dilemma. Prosthetic replacement puts them at high risk for multiple revisions. Other surgical options such as debridement, interposition arthroplasty, and resurfacing arthroplasty should be considered as alternatives to traditional hemiarthroplasty or total shoulder arthroplasty in these patients. These options are best presented as temporizing measures, used to provide some symptom relief and functional improvement without compromising bone stock required for future arthroplasty or other surgical options such as arthrodesis.

Little information is available regarding the longevity of resurfacing and interpositional arthroplasty. Levy and Copeland’s review of their series of resurfacing arthroplasties revealed that those patients with primary osteoarthritis had the best outcome, and that only 8% required revision during the 5- to 10-year follow-up.120 Several biologic-bearing surfaces have been implanted in an effort to defer glenoid degeneration, including Achilles’ tendon allograft, lateral meniscus, anterior capsule fascia, and decellularized matrices. Unfortunately, none of these approaches have been able to consistently restore function and provide pain relief to the shoulder.56,90,108 More

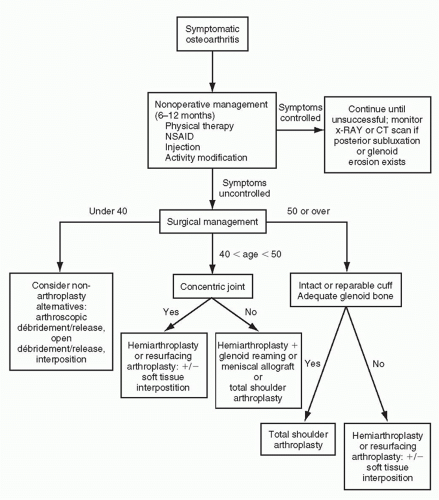

recently, osteochondral glenoid allograft has been introduced as a possible biologic resurfacing graft, but no in vivo studies have been undertaken.76 With time, biologic-bearing surfaces may provide a treatment solution to the difficult problem of glenohumeral arthritis in the young patient but at present the indications for their use have not been clearly established. A simple treatment algorithm for osteoarthritis is shown in Fig. 17-5.

recently, osteochondral glenoid allograft has been introduced as a possible biologic resurfacing graft, but no in vivo studies have been undertaken.76 With time, biologic-bearing surfaces may provide a treatment solution to the difficult problem of glenohumeral arthritis in the young patient but at present the indications for their use have not been clearly established. A simple treatment algorithm for osteoarthritis is shown in Fig. 17-5.

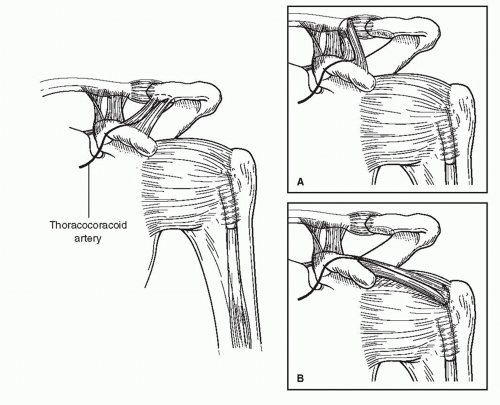

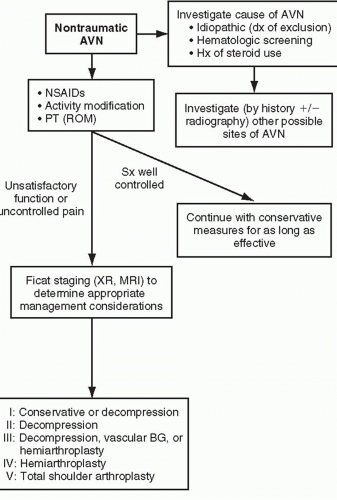

Surgical indications for patients with avascular necrosis are very similar to those for osteoarthritis. Osteonecrosis patients are generally much younger than their counterparts with osteoarthritis. However, with associated diseases such as sickle cell anemia or renal failure, their life span may be shorter. Therefore, the indications for hemiarthroplasty and total shoulder arthroplasty are based more upon the stage of avascular necrosis present, the projected life span of the patients, and the activity level of the patients, rather than their age. Stage I disease is silent and, therefore, generally does not require treatment. There is debate about whether core decompression of the humerus changes the incidence of late collapse. Obviously, if it does, stage I disease may be an indication for humeral head decompression. Until these data are available, most patients with stage I avascular necrosis are not surgical candidates. In stage II disease that does not respond to standard nonoperative treatment, core decompression with or without bone graft is indicated. Stage III (subchondral fracture) and IV (collapse) avascular necrosis may be an indication for hemiarthroplasty, depending on the degree of collapse and patient’s activity level. Stage V osteonecrosis (glenoid involvement) is an indication for total shoulder arthroplasty as long as the cuff is intact or reparable and the activity level and life expectancy are appropriate. In active patients with a normal or near-normal life expectancy, an alternative to total shoulder arthroplasty is hemiarthroplasty with soft-tissue interposition. Anecdotally, vascularized bone grafts may become a treatment option around the shoulder as it is presently utilized in the wrist. Moor et al. demonstrated the feasibility of harvesting the anterior acromion as a vascularized pedicle bone graft from the thoracoacromial artery. The pedicle has the potential to be mobilized and transferred to the humeral head without tension (Fig. 17-6).137 A simple treatment algorithm for avascular necrosis is shown in Figure 17-7.

The only absolute contraindication to prosthetic arthroplasty is active infection. Relative contraindications include concomitant rotator cuff and deltoid dysfunction, Charcot arthropathy, and severe brachial plexopathy.85 Arthroplasty in patients with a remote history of infection should be approached cautiously. Although it is impossible to predict for certain the likelihood of recurrent infection, the risk is lower in patients with greater time intervals from the original infection, normal erythrocyte sedimentation rate, normal C-reactive protein, and negative cultures.

Risks of Nonoperative Treatment

The concept of risk associated with nonoperative management may not initially seem valid. However, if one assumes that a given patient with osteonecrosis or osteoarthritis will

eventually require prosthetic replacement, the development or worsening of concomitant conditions known to have a negative effect on prognosis following arthroplasty is a relative risk of nonoperative treatment. Two such conditions in patients with osteoarthritis are stiffness (external rotation less than 10 degrees) and posterior subluxation.92 Therefore, patients with osteoarthritis and mild stiffness or posterior erosion should be counseled about the effect on prognosis of stiffness, pronounced posterior glenoid erosion, and posterior subluxation should they develop with further nonoperative management. Young patients (less than 50) with avascular necrosis should likewise be told that nonoperative management prolonged enough to develop significant glenoid involvement may subject them to the premature need for a glenoid component. Moreover, rheumatoid patients with an intact and functional cuff and good bone stock should be cautioned about the development of irreparable cuff deficiency and nonreconstructible bone loss with further nonoperative management. These treatment decisions are difficult and should be individualized; ultimately, the patient must decide between the relative risks of prosthetic replacement and nonoperative treatment.

eventually require prosthetic replacement, the development or worsening of concomitant conditions known to have a negative effect on prognosis following arthroplasty is a relative risk of nonoperative treatment. Two such conditions in patients with osteoarthritis are stiffness (external rotation less than 10 degrees) and posterior subluxation.92 Therefore, patients with osteoarthritis and mild stiffness or posterior erosion should be counseled about the effect on prognosis of stiffness, pronounced posterior glenoid erosion, and posterior subluxation should they develop with further nonoperative management. Young patients (less than 50) with avascular necrosis should likewise be told that nonoperative management prolonged enough to develop significant glenoid involvement may subject them to the premature need for a glenoid component. Moreover, rheumatoid patients with an intact and functional cuff and good bone stock should be cautioned about the development of irreparable cuff deficiency and nonreconstructible bone loss with further nonoperative management. These treatment decisions are difficult and should be individualized; ultimately, the patient must decide between the relative risks of prosthetic replacement and nonoperative treatment.

Results

Results specific to individual diagnosis are discussed at the conclusion of this chapter. However, several comments regarding the results of shoulder arthroplasty in general deserve mention here. First, it is difficult to compare the results of shoulder arthroplasty from multiple publications and is often difficult to assess the results within individual publications for several reasons. Data for pain, motion, function, patient satisfaction, and overall results have not been reported between publications with uniform methods. Factors such as method of component fixation and the status of the rotator cuff vary from report to report as well. Patients within a publication often represent a mixed group from whom the results of several diagnostic categories are tallied together and reported as a single data point. At times, results of patients receiving a humeral head replacement are not separated from patients receiving a nonconstrained total shoulder arthroplasty.

Neer et al. noted that the main factors influencing the overall results—the condition of the rotator cuff and deltoid musculature and the required details of surgery—varied depending on the diagnostic category being addressed.143 As such, Neer et al. emphasized the importance of grouping

patients to diagnostic categories when assessing the results of total shoulder arthroplasty.

patients to diagnostic categories when assessing the results of total shoulder arthroplasty.

Neer et al. reported their results using an overall results grading system that subdivided patients into two categories.143 Depending on the status of the rotator cuff and deltoid musculature and the stability of the implant at the completion of surgery, patients were assigned to either a full rehabilitation category or a limited-goals rehabilitation category. A patient was assigned to a full rehabilitation category if the muscles were intact or reparable and component stability was verified intraoperatively.143 Clinical results for full rehabilitation patients were graded as either excellent, satisfactory, or unsatisfactory, depending on the degree of patient satisfaction, pain relief, strength, and motion. An excellent result required that the patient had no pain or slight pain; had active abduction within 35 degrees of normal and 90% of normal external rotation; and was satisfied with the result. A satisfactory result was achieved if the patient had no pain, slight pain, or moderate pain only with vigorous activities; had active abduction of more than 90 degrees and 50% of normal external rotation; and was satisfied with the procedure. An unsatisfactory rating required failure to achieve any of these criteria.

A limited-goals rehabilitation category was assigned if the muscles were detached and not capable of recovering function after repair because of fixed contracture or denervation, or if the stability of the implant was judged to be problematic.143 Clinical results for the limited-goals category were graded as either satisfactory or unsatisfactory, depending on patient satisfaction, pain relief, and restoration of limited, but useful, shoulder function. A satisfactory result required no pain, slight pain, or moderate pain only with vigorous activity, active abduction of more than 70 degrees, and external rotation of more than 20 degrees.

Pain relief is the most predictable benefit of total shoulder arthroplasty and appears to vary little between diagnostic categories. Approximately 90% of patients can be expected to attain good or excellent pain relief. When inadequate pain relief occurs, the source is often explained by an identified intraoperative or postoperative complication. More common reasons for inadequate pain relief include glenoid component loosening, malpositioning of the components, improper soft-tissue balancing, rotator cuff tears, inadequate postoperative rehabilitation, and infection. In our experience, it is uncommon for inadequate postoperative pain relief to lack explanation.

Range of motion has been a difficult area of assessment, because only recently a standardized system for measuring motion has been recognized.162 Assuming the arthroplasty was technically well performed, and postoperative rehabilitation has been adequate, than range of motion most directly correlates with the status of the rotator cuff and deltoid musculature. Osteoarthritis and osteonecrosis rarely have rotator cuff tears and most consistently obtain the greatest motion. Full or close to full active range of motion is not unusual postoperatively.10,41,87,143 Gains in motion in rheumatoid arthritis patients are more variable, and several factors are likely responsible. The severity of disease varies and often affects other joints that interfere with the ability to rehabilitate the shoulder. The quality of the rotator cuff tissue is often compromised, being either atrophic or possessing tears of variable size and thickness.41,101,134 In general, the longer the disease process persists, the more atrophic the deltoid musculature becomes and the greater is the rotator cuff involvement.

Therefore, it should be anticipated that rehabilitation in rheumatoid patients will require more time.143,147

Therefore, it should be anticipated that rehabilitation in rheumatoid patients will require more time.143,147

The functional results of nonconstrained total shoulder arthroplasty have been obtained by measuring the patient’s ability to perform specific tasks of daily living. Most functional grading systems include activities that require varying degrees of forward elevation of the arm, with many being performed at waist level and fewer being performed at shoulder level or higher. Functional evaluation systems vary from report to report, making comparison between studies difficult. In the publications in which patients are separated into groups, based on diagnosis, functional scores are consistently higher in osteoarthritis than in rheumatoid arthritis. Functional scores tend to be lower for arthroplasty performed for old trauma.9,10,143 The functional results of shoulder arthroplasty are dependent on both pain relief and gains in active range of motion. A patient who does not obtain gains in motion, but has less pain, is more inclined to use the extremity in functional activities within the range of motion available to him or her. This is especially so in patients who require only lowdemand use of the extremity within limited arcs of motion. However, if significant gains in active range of motion are also achieved, the patient can participate in a broader spectrum of functional activities.

Our review of the literature yielded over 50 publications reporting the results of nonconstrained shoulder arthroplasty for glenohumeral arthritis and an intact or reparable cuff.4,5,6,7 and 8,10,11,15,22,24,28,32,34,39,40,41 and 42,44,46,47,49,50,53,55,58,61,62,67,70,75,78,79 and 80,82,83,87,97,100,101,105,120,121 and 122,125,126,128,129,131,132 and 133 Reports of patients with rheumatoid or inflammatory arthritis were included, despite the fact that some of the included patients had dysfunctional or irreparable rotator cuffs. Only 10 of these reports had a minimum 5-year followup and, therefore, were considered at least midterm followup.46,50,82,122,126,173,177,178,187,189 Only two studies had a minimum 10-year follow-up50,180 and only five provided predicted survivorship.28,50,126,177,178 While the data from these reports are not completely comparable, some conclusions can be made. First, shoulder arthroplasty results in predictable and durable pain relief. Second, functional results vary with rotator cuff integrity but are also predictable and durable in patients with an intact or reparable cuff. Third, rotator cuff disease continues after arthroplasty in many patients with inflammatory arthritis as evidenced by progressive proximal humeral migration.173 Finally, survivorship varies with age and activity level but, in general, is 95% to 98% at 5 years, 93% to 97% at 10 years, 84% to 88% at 15 years, and 80% to 85% at 20 years.50,126,178

Plain film evaluation has shown the prevalence of glenoid radiolucent lines to range between 30% and 80% at various periods of follow-up.10,26,41,143 However, the high prevalence of radiolucent lines has not correlated strongly with the presence of symptoms. As such, the significance of these lines remains a controversial subject. Of 46 reoperations performed at the Mayo Clinic between 1976 and 1988 addressing complications of nonconstrained total shoulder arthroplasty, 13 (28%) were for glenoid loosening.45 As in the Mayo Clinic article, most articles report that the most common prosthetic-related complication of total shoulder arthroplasty is glenoid component loosening. The need for reoperation for this problem was summarized from 19 reports (1,413 procedures) by Brems.25 At an average of 5 years of follow-up, radiolucent lines were present in 546 (38.6%) procedures, and in 42 (2.9%) reoperation was required for glenoid component loosening. The rate of radiolucent lines requiring revision glenoid surgery was 7.7% (42 of 546). Therefore, relatively few of these radiolucencies became symptomatic at midterm follow-up. The incidence of radiographic evidence of glenoid component loosening appears to increase with longer periods of follow-up.29,188

PREOPERATIVE EVALUATION

History

Patients with primary osteoarthritis typically present with an insidious onset of pain, which has been slowly progressive over past years. Progressive stiffness is often associated with the discomfort. As is the case in other arthritic joints, the pain is often activity-related. Stiffness is most notable after a period of immobilization, and improves with gentle motion.

Patients’ complaints will often relate to functional limitations such as difficulty internally rotating to reach their back pocket or fastening a brassiere. Questioning patients as

to how their symptoms have interfered with their daily routines will provide insight into the degree of pain and disability. Understanding the patients’ occupation, hobbies, and activity levels also helps gauge the impact of their disease. Documentation of treatments that have been or are being used also gives information about disease course and severity.

to how their symptoms have interfered with their daily routines will provide insight into the degree of pain and disability. Understanding the patients’ occupation, hobbies, and activity levels also helps gauge the impact of their disease. Documentation of treatments that have been or are being used also gives information about disease course and severity.

Awareness of the patients’ profile of comorbidities is important not only for presurgical screening, but also as a means of evaluating what other conditions might limit activity and rehabilitation.

Patients suspected of having avascular necrosis should also be questioned regarding the onset, course, severity, and impact of their symptoms as this is valuable information in management decision making. Typically, these patients are younger than those presenting with osteoarthritis. Identification of risk factors can aid in determining the cause of osteonecrosis. Exposure to steroids, alcohol use/abuse, liver pathology, and personal or family history of coagulation disorders should be addressed. Careful questioning about pain in the contralateral shoulder and other joints at risk (hips, knees, ankles, etc.) is also important. Although only 3% of patients with osteonecrosis have multifocal involvement,112,113 80% of patients with multifocal osteonecrosis will have humeral head involvement.112

Physical Examination

A complete shoulder examination should be performed with particular attention to range of motion. Typically, both osteoarthritis and avascular necrosis cause progressive global loss of motion, with particular loss of external rotation. Postcapsulorrhaphy often has the most severe loss of external rotation. Any internal rotation contracture must be noted and documented as it dictates how the subscapularis release is managed at the time of surgery. Active and passive motion should be compared and the rotator cuff strength noted. This can be sometimes difficult to determine on physical examination alone, as there is often pain-related weakness. Painful crepitus is common. Tenderness to palpation over the acromioclavicular joint can indicate arthritis, which potentially can contribute to the symptom complex. This is an important finding to identify as it can also be addressed at the time of surgery if needed.

Imaging Studies

Plain radiographs are the single most important investigation required in the diagnosis of osteoarthritis and arthroplasty planning. A standard X-ray series (anteroposterior [AP], transscapular lateral, and axillary lateral) is typically performed, and each provides different information required for preoperative preparation. The AP X-ray, which often is done in internal and external rotation, allows assessment of bone quality, identification of inferior osteophytes, and diameter of the humeral canal. Preoperative templating is performed using the AP and axillary views. Also, although not universally reliable because of slight variations in angle-of-beam projection, the evaluation of the acromiohumeral distance can suggest the presence of significant rotator cuff deficiency if the distance measures less than 7 mm. The axillary radiograph is useful in identifying glenoid version as well as the posterior glenoid wear and resultant posterior subluxation that is often associated with osteoarthritis (Fig. 17-8).

FIGURE 17-8. Axillary radiograph revealing posterior glenoid erosion associated with posterior subluxation that is commonly seen in osteoarthritis. |

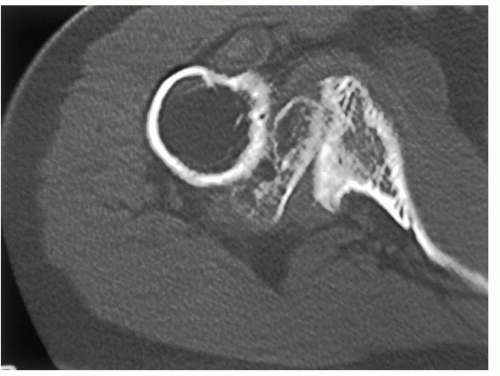

A computed tomography (CT) scan provides a more definitive assessment of glenoid bone stock and version. It also allows accurate determination of whether glenoid replacement is feasible and if bone grafting may be necessary (Fig. 17-9). One radiographic study of a series of patients with primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis who were awaiting shoulder arthroplasty found that 45% have posterior subluxation.192 Average glenoid retroversion in this population was found to be 15.4 degrees (normal being 1 to 2 degrees of retroversion).71 Three studies have revealed inaccuracies in measuring glenoid version using standard radiographs and two-dimensional (2-D) CT scans21,33,149 and determined that the use of 3-D CT scan imaging can measure more accurately the glenoid version and help assist in preoperative planning for patients with posterior glenoid bone loss with osteoarthritis.167 Humeral version can

also be determined from CT pictures of the humeral head and its relation to the transcondylar axis.88 Since posterior glenoid erosion and posterior subluxation are common with severe internal rotation contracture, 3-D CT scanning is ordered in all patients with external rotation of 30 degrees or less.

also be determined from CT pictures of the humeral head and its relation to the transcondylar axis.88 Since posterior glenoid erosion and posterior subluxation are common with severe internal rotation contracture, 3-D CT scanning is ordered in all patients with external rotation of 30 degrees or less.

FIGURE 17-9. Computed tomographic scanning can be used to quantitate the amount of posterior glenoid deficiency and posterior subluxation. |

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be useful in cases of suspected rotator cuff tear. In general, full-thickness rotator cuff tears are exceedingly uncommon in patients with osteoarthritis or osteonecrosis (5%). However, in patients who have had prior rotator cuff surgery or demonstrate a decreased acromiohumeral distance on plain radiography, rotator cuff tears may be more common. Under these circumstances, MRI scanning can reveal glenoid erosion, abnormal glenoid version, and full-thickness rotator cuff tears.

MRI is also useful in staging avascular necrosis. Moreover, avascular necrosis in certain disease states, such as renal failure, may be associated with rotator cuff deficiency. Therefore, MRI scanning is performed frequently in patients with early avascular necrosis, particularly when it is associated with renal failure.

Implant Choices

When considering the humeral side, the choice of implants generally is between traditional stemmed humeral replacement and humeral head resurfacing. The advantages of traditional stemmed implants include easier glenoid exposure, greater familiarity, and a larger and longer experience. However, replacement of the humeral head with a stemmed implant requires greater bone removal, potentially more extensive exposure, and potentially a greater number of implant choices to recreate normal humeral anatomy. The humeral head resurfacing without a stemmed implant is a very reasonable option in patients with adequate bone stock, a concentric or minimally diseased glenoid, and a need for bone preservation (i.e., a young patient with high likelihood for revision). Although glenoid resurfacing is possible without removing the head, it is more difficult than with the head removed. The results of humeral head resurfacing are promising but sparse. Levy and Copeland’s review of their series of resurfacing arthroplasties revealed that those patients with primary osteoarthritis had the best outcome, and that only 8% required revision during the 5- to 10-year follow-up.120

Stemmed humeral head replacements are the most popular humeral implants for shoulder replacement, particularly when the glenoid is also being resurfaced. There are many stemmed humeral implants available and none has been shown to be superior to others with regard to clinical outcome. The principles that have gained in popularity and have some basis in scientific evidence include humeral head modularity, humeral head offset, and anatomic reconstruction.19,63,91,154

There is a large variety of glenoid replacement prostheses also available for shoulder arthroplasty. These include all-polyethylene designs, metal-backed designs, and hybrid designs with metal peg sleeves but no metal backing. At present, all-polyethylene designs report the most consistent and reliable outcomes.68,73,186 There is also variability with regard to articular conformity and constraint. There is some evidence to show that arthroplasties characterized by nonconforming radii of curvature yield more physiologic translations and exhibit lower loosening scores than conforming designs.99,193 However, more data are necessary to confirm this. At the very least, the surgeon should be familiar with the conformity characteristics of the glenoid being used so that excessive contact stresses are not created.

SURGICAL APPROACHES

This section will discuss the preferred surgical approach, anesthesia, patient positioning, surgical technique, and implant considerations for shoulder arthroplasty, with particular emphasis on considerations specific to osteoarthritis, avascular necrosis, and other conditions characterized by an intact or reparable rotator cuff.

Preferred Approach

Shoulder arthroplasty is a demanding surgical procedure, the outcome of which is at least partially the result of balancing the concepts of surgical exposure and preservation of soft tissues. Several surgical exposures have been described for shoulder replacement, including superior acromial splitting, superior deltoid-reflecting, anterior deltoid-reflecting (with and without clavicular osteotomy), posterolateral posterior cuff-reflecting, superolateral deltoid-reflecting, and anterior deltopectoral deltoidsparing approaches.52,74,98,107,111,140,143,160 The deltoid-reflecting approaches offer superior exposure at the expense of potential deltoid morbidity or osteotomy nonunion. Fortunately, in cases of primary osteoarthritis and nontraumatic avascular necrosis, virtually every reconstructive situation encountered can be adequately performed through the deltopectoral approach described and popularized by Neer, without detaching the deltoid origin or insertion. This is even true in cases of osteoarthritis requiring posterior glenoid bone grafting. Therefore, our preferred approach for primary osteoarthritis, nontraumatic avascular necrosis, and other conditions with an intact or reparable cuff is an extended deltopectoral approach.140,143

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree