Ulnar Collateral Ligament Reconstruction of the Elbow

Sameer Nagda

Michael Ciccotti

DEFINITION

The ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) is a primary stabilizer of the medial side of the elbow. A tear in this ligament can cause pain and disability, primarily in an overhead athlete. When reconstruction is performed, the anterior band of the ligament is reconstructed.

ANATOMY

The UCL originates from the inferior aspect of the medial epicondyle and inserts onto the sublime tubercle of the ulna.

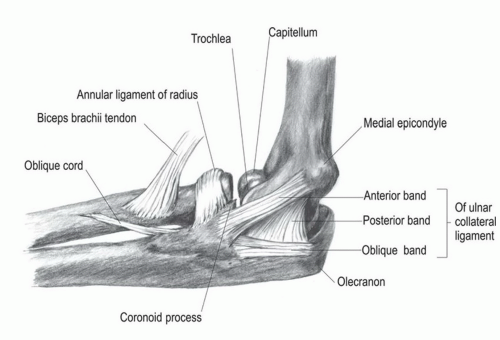

There is an anterior band, a posterior band, and a transverse band (FIG 1).

The anterior band provides the primary resistance to valgus stresses between 20 and 120 degrees and is further divided into anterior and posterior bundles that tighten in a reciprocal fashion as the elbow is flexed and extended.

PATHOGENESIS

Injury to the UCL occurs with a valgus force applied to the elbow. This can occur from trauma such as a fall on an outstretched hand. Injury is most commonly seen in the overhead athlete who applies a significant and repetitive valgus force to the elbow during sports.

Injury is most common in baseball, javelin, and volleyball but can be seen in numerous other sports such as football, wrestling, and tennis.

NATURAL HISTORY

Injury to the UCL can occur in one instance with immediate onset of pain or can be progressive over a period of time.

Patients who do not repeatedly expose the injured ligament to continued stress have a high rate of success with nonsurgical treatment if gross elbow instability is not present.

Athletes participating in sports that place a valgus stress on the elbow and who wish to continue to participate will usually require surgical reconstruction to resume participation.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Patients will complain of pain on the medial side of the elbow. There may be associated complaints of numbness and/or tingling if there is concurrent irritation to the ulnar nerve.

Patients may describe feeling a pop in the elbow with one incident of a valgus force, such as a baseball pitch or javelin throw. Conversely, there may be a history of several days or weeks of progressive, worsening medial elbow discomfort, tightness, or trouble with activity involving valgus force to the elbow.

Patients with isolated UCL injury will rarely complain of instability. Unless concurrent flexor-pronator mass (FPM) or ulnar nerve injury is present, patients will rarely complain of weakness.

In addition to a thorough basic elbow examination as described previously, provocative tests to diagnose UCL tears

include the moving valgus stress test and the milking test. Pain along the UCL elicited with these tests is indicative of a UCL tear.

The milking test is performed by pulling or “milking” the thumb of the involved elbow while placing a valgus force on the elbow. The involved shoulder is held in an abducted and externally rotated position while the test is performed.

The moving valgus stress test is performed in a similar position, but the involved elbow is moved from 30 to 120 degrees while valgus stress is applied to the elbow.

Direct valgus stress testing may also cause pain. However, the examiner will rarely appreciate laxity with this test. This test should be performed in approximately 30 to 60 degrees of elbow flexion.

Palpation of the posteromedial olecranon may elicit pain in chronic situations of valgus extension overload.

Chronic microlaxity may also result in lateral-sided compression, causing overload of the radiocapitellar joint. Palpation of this area should be performed for pain or crepitans.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Initial plain radiographs are helpful especially in younger individuals. These may reveal bony avulsion of the ligament, growth plate fracture, posteromedial olecranon osteophytes, or osteochondritis dissecans (OCD) of the capitellum. Plain radiographs in more mature throwing athletes often show calcifications and or osteophytes. Stress radiographs may be helpful in cases of significant instability.

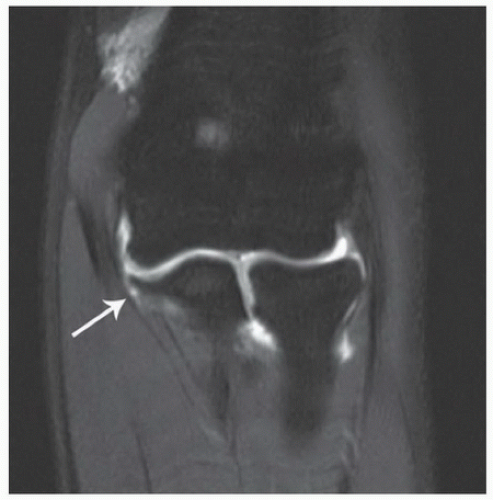

The imaging of choice is an elbow magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with or without intra-articular contrast.

The T-sign is a finding often seen on an MRI and is suggestive of injury to the UCL (FIG 2). In cases where an MRI cannot be attained, a computed tomography (CT) arthrogram can be used to diagnose injury to the UCL.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

FPM injury/medial epicondylitis

Medial epicondyle fracture

Ulnar neuritis

Ulnar stress fracture

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Nonoperative treatment consists of rest, oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and rehabilitation focused on shoulder and scapular strengthening along with evaluation of the specific mechanics involved in each athlete’s sport.

Athletes who are not involved in overhead sports may return when symptoms allow and may participate with a hinged elbow brace.

Athletes involved in overhead sports often require a 3- to 6-week period of rest, during which time a coordinated rehabilitation program including leg, core, and shoulder strengthening and flexibility is carried out. Once preinjury range of motion (ROM) and strength are restored without pain, then a progressive throwing program is initiated. This program includes tossing at increasing distance up to ˜180 to 200 feet; pitchers then begin a mound program throwing fastballs first with increasing effort, followed by off-speed pitches. This thorough nonoperative program may require 8 to 12 weeks before return to sport.

Certain overhead-throwing athletes have high success with nonoperative measures. Dodson et al6 noted that professional football players, specifically quarterbacks, have a high rate of return with nonoperative treatment.

Podesta and associates12 reported an 88% return to competition for athletes with partial tears of the UCL treated with platelet-rich plasma (PRP) in short-term follow-up.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Surgical management is considered for all athletes who fail nonoperative treatment.

Surgical management consists of reconstruction of the anterior band of the UCL. Most commonly, a palmaris longus autograft is used if available. Alternatives include contralateral hamstring, plantaris, or medial strip of Achilles

tendon autograft. Allograft reconstruction has also been described recently with good results.14

Preoperative Planning

Preoperative planning should include evaluating if the patient has an available palmaris longus tendon. If not, alternative graft options should be discussed with the patient. The palmaris longus tendon has been identified in 85% of the population.

Patients with ulnar nerve symptoms should be evaluated for possible ulnar nerve decompression or transposition performed at the time of UCL reconstruction. A subluxing ulnar nerve should also be identified and considered for surgical treatment.

Concurrent intra-articular pathology such as loose bodies can be managed with arthroscopy at the time of reconstruction.

Patients with acute injuries should be evaluated for return of full elbow motion prior to undergoing surgery.

Positioning

The patient is placed in the supine position with a hand table. If elbow arthroscopy is to be performed, the patient should be positioned for this in the desired position first and then switched to the supine position.

Either a sterile or nonsterile tourniquet can be used.

If a hamstring, plantaris, or medial Achilles strip autograft is to be taken, the contralateral leg should also be draped out and a nonsterile tourniquet should be used.

Approach

The approach consists of a standard medial incision centered over the medial epicondyle (FIG 4). The initial surgery described by Jobe et al11 consisted of a takedown of the FPM and ulnar nerve transposition.

More recent modifications describe an FPM split and ulnar nerve transposition only if indicated.15

Commonly used techniques include the Jobe figure-of-eight technique and the docking technique. Biomechanical evaluation of both techniques has revealed valgus stability comparable to the native ligament.3

TECHNIQUES

▪ Figure-of-Eight Reconstruction—Jobe Technique

An extensile medial incision is used centered over the medial epicondyle.

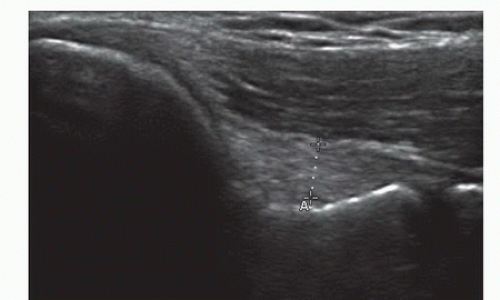

Care should be taken to identify and protect the branches of the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerves (TECH FIG 1A).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree