Treatment of Recurrent Posterior Shoulder Instability

Jeffrey S. Noble

Matthew B. Noble

Robert H. Bell

DEFINITION

Symptomatic recurrent posterior instability represents up to 12% of all cases of shoulder instability and is subdivided into two discrete entities.32,40

The first, true posterior dislocation is acute in nature and often related to trauma. It is readily managed with shoulder reduction and carries a low recurrence rate if not associated with a large engaging humeral head defect or a primary uncontrolled seizure disorder.

If the primary dislocation is overlooked, this condition can manifest itself as a chronic locked posterior dislocation with its pathognomonic internally rotated position and loss of external rotation on physical examination.

The second entity is recurrent unidirectional posterior subluxation, which often represents the more challenging dilemma confronting the orthopaedic surgeon and will be the principal topic of this chapter.

Whether due to an increase in awareness by physicians or a more active athletic population, recurrent unidirectional posterior instability is being recognized, diagnosed, and treated more frequently.

Patients with recurrent posterior subluxation complain primarily of pain and weakness. As time progresses, symptoms of posterior subluxation become a secondary complaint. Eventually patients often learn the selected muscular contractions, scapular winging, and arm position (forward elevation, adduction, and internal rotation) needed to demonstrate their instability.

See Table 1 for the classification of posterior instability.

ANATOMY

Posterior instability may be secondary to a tear of the posteroinferior labrum or a patulous posterior capsule.

Table 1 Classification of Posterior Instability

Acute posterior dislocation

Without impression defect

With impression defect

Chronic posterior dislocation

Locked (missed) with impression defect

Recurrent posterior subluxation

Voluntary

Habitual (willful)

Muscular control (not willful)

Involuntary

Positional (able to demonstrate)

Nonpositional (unable to demonstrate)

Rarely, it can involve a posterior labrocapsular periosteal sleeve avulsion or an avulsion of the posterior glenohumeral ligaments as they insert on the humerus (posterior humeral avulsion of glenohumeral ligament [HAGL] lesion).

Recently, Kim et al24 described a concealed and incomplete avulsion of the posteroinferior labrum (type II marginal crack or Kim lesion).

Pathology may also be bony in nature and secondary to posterior glenoid avulsions, erosions, increased glenoid retroversion, or large engaging reverse Hill-Sachs impression defects.

PATHOGENESIS

A significant percentage of patients (40% to 50%) with recurrent posterior subluxation relate a history of trauma. Usually athletes, these individuals are typically 18 to 30 years of age and are involved in competitive contact sports.

Traumatic cases are often associated with an injury where the arm is in a straight and locked position such as in weightlifting or during football while line blocking. A fall or collision with the individual’s arm in the at-risk position (forward elevation, adduction, internal rotation) can also be the cause.

Frequently, instead of a traumatic event, subluxation episodes with a poorly defined onset are the initial presentation.

In many cases, especially with repetitive overhead endeavors such as swimming, gymnastics, baseball, and volleyball, the athlete recalls first the gradual onset of discomfort, with subluxation episodes occurring later. Such an onset is thought to be atraumatic and involves repetitive “microtrauma” with resultant stretching of the capsular restraints.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Whether the patient presents with a clear traumatic episode or a longer atraumatic course, he or she often has a feeling of the shoulder “coming out.” Such instability episodes occur when the arm is in the at-risk position of forward elevation, adduction, and internal rotation.

Patients often describe a vague discomfort, pain, or weakness as their principal complaint. This actually may lead to misdiagnosis at first.

True apprehension or a feeling of “impending doom” when the extremity is placed in the provocative position is less common but can be present.

Overhead throwers may complain of a loss of velocity, fatigue, or aching over the posterior shoulder.

Usually, there is no obvious asymmetry of the muscles on inspection.

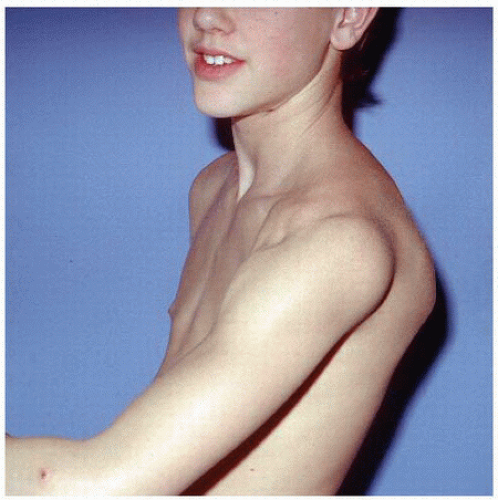

FIG 1 • Younger patient able to voluntarily demonstrate, with muscular contraction and positioning of the upper extremity, his posterior instability.

Palpation may elicit some tenderness along the posterior glenohumeral joint line.

Crepitation or a click along the posterior joint line due to labral pathology may be noted.

The range of motion is full, often with a decrease in internal rotation and an excess of external rotation.

Often, patients, if voluntary subluxators, can reproduce the subluxation episode on command with arm position and selective muscular contraction (FIG 1).

Physical examination should include the following:

Modified load shift test: documents direction and degree of instability

Supine load shift test (Gerber and Ganz16): documents direction and degree of instability

Seated load shift test: documents direction and degree of instability

Posterior stress test: documents direction and degree of instability

Sulcus sign: evaluates for an inferior component of the posterior instability (bidirectional) or a more global instability (ie, multidirectional instability)

Scapular compression test: verifies the importance of scapular winging in the patient’s ability to reproduce the instability and proves to the patient the need to strengthen the periscapular musculature to control instability

Jerk test: to document instability. A painful jerk test suggests a posteroinferior labral lesion and is a predictor of the success of nonoperative treatment.

Kim test: evaluates for the presence of a labral tear posteriorly

Pivot shift of the shoulder: documents direction of the instability

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Radiographic evaluation includes a three-view trauma series of the shoulder, including a true anteroposterior (AP) view of the shoulder, a scapular lateral, and, more importantly, an axillary view.

A Velpeau axillary view can be substituted if the attempted axillary view is impossible because of painful abduction of the shoulder.

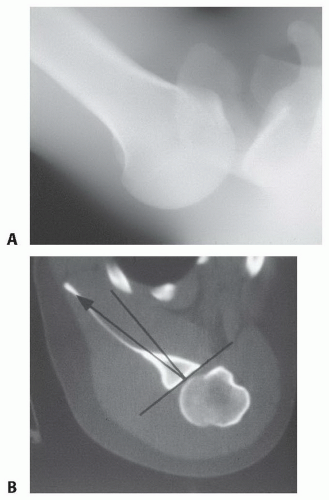

Axillary radiographs of patients with a voluntary component to their instability can be taken while the patient reproduces and maintains the subluxation episode to document the direction (FIG 2A).

A computed tomography (CT) scan can be helpful to evaluate humeral head defects and associated fractures of the tuberosities, humeral shaft, and posterior glenoid rim. Significant posterior glenoid retroversion can also be demonstrated on CT scanning (FIG 2B).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the imaging modality of choice after plain radiographs to evaluate the posterior capsule and labrum for tears and associated pathology.

In certain situations, an MRI arthrogram can help diagnose a posteroinferior labral tear.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Superior labrum anterior to posterior tear (SLAP)

Anterior instability

Multidirectional instability

Internal impingement

Posterior Bennett lesion

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Nonsurgical treatment of posterior unidirectional instability is reportedly successful in up to 80% of the patients.11,21

The physical therapy program consists of concentric and eccentric resistive band exercises that strengthen the external rotators, the deltoid, and the important periscapular musculature.

Resistive upright and seated rows, with an emphasis on trying to pinch the medial scapular borders together during the exercise, are key, especially in patients whose scapular winging contributes to their instability.

A strengthening program as well as a sport-specific attempt to decrease those activities that place the arm at risk is key.

The length of nonoperative treatment must be individualized.

Patients who have lower physical demands, are younger, and those with an atraumatic history are treated 6 months or more.

Higher level athletes or those who have a traumatic cause with an associated labral tear are more likely to require surgical treatment. Despite their associated labral tears, such elite athletes are often treated with an exercise strengthening program for at least 3 months.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Although open procedures have been the mainstay and gold standard in the treatment of patients with recurrent unidirectional posterior subluxation, arthroscopic treatment has become common.

As with anterior instability, arthroscopic evaluation in posterior instability patients has led to the diagnosis and treatment of an increasing number of associated soft tissue and articular injuries. Obviously, arthroscopic treatment of posterior capsular avulsions or redundancy in the absence of soft tissue deficiencies or bony abnormalities can have similar success rates without the morbidity of more extensive open surgery.2,7,24,25,27,38

Surgical treatment is considered only after an adequate trial of strengthening has failed and the patient remains significantly symptomatic.

The ideal surgical candidates are those with recurrent posterior unidirectional subluxation secondary to a traumatic episode. These patients often have an associated traumatic posterior labral tear, which is optimal for arthroscopic repair.

Patients with atraumatic subluxation due to capsular redundancy can be managed either through an open procedure or an arthroscopic capsular shift or plication procedure.

Patients who have multifactorial causes for their instability or are revision situations may be treated better with an open approach.

Preoperative Planning

An extensive history and physical examination are key to establishing the direction and degree of the patient’s instability.

All imaging studies are reviewed. Plain films and MRI studies are reviewed for the presence of old fractures, loose bodies, and hardware from previous procedures. More importantly, the MRI establishes whether the instability is due to an associated traumatic posterior labral tear or capsular redundancy.

Associated bony pathology (traumatic glenoid avulsions, glenoid retroversion) and soft tissue deficiencies (from previous procedures) should be addressed concurrently.

In rare instances, a sizable reverse Hill-Sachs lesion may exist and can be treated in an arthroscopic or open manner.12

Examination, this time under anesthesia, should be accomplished before positioning to confirm the direction and degree of the instability.

TECHNIQUES

▪ Arthroscopic Posterior Reconstruction (Authors’ Preferred Technique)

Positioning

The patient is positioned in a lateral decubitus position with the operative arm placed in about 40 degrees of abduction and no more than 10 pounds of longitudinal traction.

All pressure points are carefully identified and an axillary roll is placed under the down axilla.

The patient’s body is placed close to the operating surgeon and tipped posteriorly 15 to 20 degrees.

We do not employ a double-traction setup as we do in anterior instability because increased adduction tends to close down visualization of the posteroinferior joint line, and we have found optimal visualization with 40 degrees of abduction when viewing from the anterior portal.

Portal Placement

Most posterior reconstructions are performed using only two portals.

The posterior portal is established just lateral to the posterior lateral corner of the acromion.

This differs from the traditional posterior viewing portal, which is 1 cm medial and 2 cm inferior from the posterior lateral corner of the acromion.

Lateralization of this portal and moving it somewhat superiorly provides an optimal angle of attack to the posterior and inferior portion of the posterior glenoid.

The anterior portal is established in the rotator interval under direct visualization using needle localization.

A 6.5-mm cannula is established to allow insertion of the arthroscope and an 8-mm cannula is placed in the posterior portal to allow the passage of the Spectrum crescent suture-passing devices (ConMed Linvatec, Largo, FL).

Site Preparation

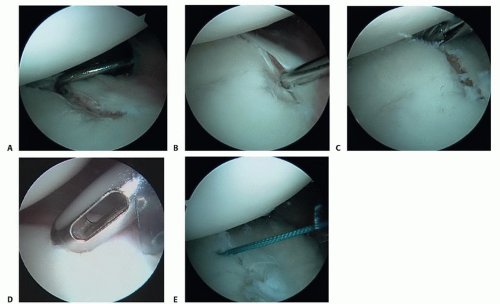

Repair is begun by assessing the posterior labral construct for the presence of labral displacement and tearing (TECH FIG 1A).

A grasper is used to capture the posterior band of the inferior glenohumeral ligament (IGHL), attempting to mobilize it superiorly to determine the amount of capsular laxity and ultimate position for repair.

If a posterior Bankart lesion is identified, a Liberator knife (ConMed Linvatec) is used to mobilize the labrum (TECH FIG 1B), and a burr is used to débride the posterior face of the glenoid in preparation for anchor placement (TECH FIG 1C).

This is a critical step so that a freely mobile labrum can be placed up on the glenoid, thereby restoring its bumper effect. Anchor placement begins at the most inferior aspect of the glenoid, usually the 5:30 or 6:30 position, depending on the side involved (TECH FIG 1D).

This position allows secure placement of an anchor while allowing optimal inferior capsular plication. Bioabsorbable anchors are employed for this reconstruction (TECH FIG 1E).

Suturing

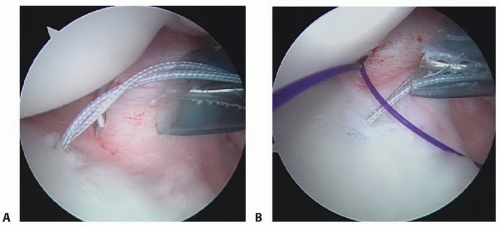

A Spectrum 45-degree-offset suture passer, preloaded with a no. 0 polydioxanone (PDS) monofilament suture (Ethicon, Somerville, NJ), is passed through the posterior cannula, capturing the inferior capsule in the area of the posterior band of the IGHL (TECH FIG 2A).

This tissue is brought superiorly and the second pass comes deep, exiting at the posterior labral defect.

The PDS suture is reeled into the joint through the passer and retrieved in the posterior cannula using a ring grasper (TECH FIG 2B,C).

The deep limb of the PDS is tied to one limb of the anchor suture, and using a pulling technique, the PDS is drawn in a retrograde fashion, with the anchor suture attached, through the capsule and labral tissue, thereby creating a simple stitch (TECH FIG 2D).

This allows the inferior capsule to be drawn superiorly and medially while at the same time closing the posterior Bankart lesion.

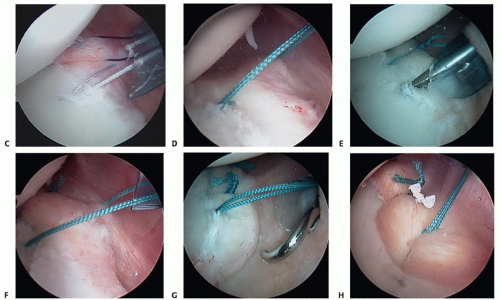

A second suture is placed after tying the first suture in a similar fashion, again incorporating the capsule as well as labrum (TECH FIG 2E,F).

This process is repeated as many times as is necessary, moving superiorly at 6- to 8-mm increments, thereby obliterating any labral defect and capsular redundancy (TECH FIG 2G,H).

Capsular Plication

Alternatively, if no labral detachment is identified and only excessive capsular redundancy exists, a posterior superior capsular shift without anchors is performed.

The posterior capsule is lightly abraded with a synovial shaver or rasp to promote healing.

A Spectrum suture passer is used again to pierce the capsule 1 cm lateral to the labrum at the 6:30 position on the glenoid.

The capsule is then advanced superiorly and medially, with the suture passer reentering the joint at the junction between the intact labrum and the glenoid rim articular cartilage.

This is repeated at least two or three times, depending on amount of laxity.

With each suture, the capsule is advanced about one hour’s position on the glenoid face (ie, 6:30 capsular stitch to the 7:30 labral position, 7:30 to 8:30, and so on).

Rotator Interval Plication

In individuals with a significant component of ligamentous laxity, additional closure of the rotator interval is accomplished by moving the arthroscope back to the posterior portal.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree