Total Shoulder Replacement: Managing Soft-tissue Deficiencies

Wayne Z. Burkhead Jr

William H. Paterson

Robert J. Nowinski

Jonathan E. Buzzell

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

Management of the soft-tissue-deficient arthritic shoulder presents a formidable challenge to the operating surgeon. The most common soft-tissue defect likely to be encountered during shoulder arthroplasty is rotator cuff deficiency. In our practice, reverse shoulder arthroplasty has supplanted most of the soft-tissue techniques presented in the last edition. Yet, there are still some patients whose young age or high activity level make them less than ideal candidates for a reverse prosthesis. In addition, the reverse prosthesis can fail. The surgeon dealing with failed reverse shoulder arthroplasty may find some of the techniques presented here helpful. Nonconstrained total shoulder arthroplasty is indicated when the rotator cuff tear is reparable. Prosthetic glenoid replacement is not recommended when the rotator cuff is nonfunctional.

Patients may also present with deltoid deficiency in conjunction with glenohumeral arthritis. The usual cause is related to previous surgery with dysfunction related to a nerve injury or dehiscence. Rarely, an axillary mononeuropathy may be traumatic in origin. While a very rare operation in anyone’s hands, we will present the results of a unique latissimus dorsi transplant that can be done to improve soft-tissue coverage and flexion strength in patients with a deltoid palsy should arthroplasty rather than fusion be the patient’s choice or in patients with an existing arthroplasty.

Specific contraindications to conventional total shoulder arthroplasty include neurologic conditions resulting in severe weakness of the deltoid and rotator cuff and an irreparable or unreconstructible detachment or denervation of the deltoid.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

A detailed history and physical examination are performed. Patients with cuff-deficient shoulders are typically elderly (seventh decade or older) and female, oftentimes with multiple comorbidities and occasionally with balance issues resulting in frequent falls. Patients with osteoarthritis and small rotator cuff tears often relate a history of progressive pain and stiffness. An acute traumatic event causing increased weakness and pain may occur. Long-standing cuff tears may be asymptomatic until a minor event results in a biomechanical “tipping point.” Rheumatoid patients generally have a long history of polyarthritis, deformity, and medical treatment for

their systemic disease. Rotator cuff tear arthropathy patients present with pain and loss of motion and oftentimes swelling and occasionally bruising with atrophy of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles and a “fluid sign” on examination.

their systemic disease. Rotator cuff tear arthropathy patients present with pain and loss of motion and oftentimes swelling and occasionally bruising with atrophy of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles and a “fluid sign” on examination.

The preoperative integrity of the subscapularis muscle is very important. Results of total shoulder arthroplasty are significantly worse when the subscapularis is ruptured (1). The lift-off and belly-press tests provide an assessment of subscapularis muscle function. An increased amount of passive external rotation compared to the normal contralateral side can also indicate deficiency of this tendon. A high suspicion for this condition should be maintained in the evaluation of any patient who has had previous surgery on or through the subscapularis.

Our standard radiographic evaluation includes anteroposterior (AP) views in internal and external rotation and an axillary view. For patients with a prior surgical procedure, we add an AP view in neutral rotation and a scapular Y view. Osteoarthritis is associated with subchondral sclerosis and cyst formation, humeral head and glenoid osteophytes, and posterior erosion of the glenoid. In contrast to rheumatoid arthritis and cuff tear arthropathy, osteopenia is not characteristic of conventional osteoarthritis. Relatively symmetric juxta-articular erosion and minimal subchondral sclerosis and osteophyte formation characterize rheumatoid shoulders. Rotator cuff tear arthropathy findings include humeral head collapse, periarticular osteopenia, reduced acromiohumeral distance, and erosions of the glenoid, acromion, and acromioclavicular joints.

Other causes of glenohumeral degeneration include trauma, metabolic arthritis, neuropathic arthropathy, osteonecrosis, hemophilic arthropathy, and septic arthritis. History and laboratory workup will usually clarify the specific etiology.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is helpful in patients who have had no previous surgery. Despite reports of success with MRI in the postarthroplasty patient (2), our experience has been less than satisfactory. Computed tomography arthrography is done to visualize bone deficits and when MRI is contraindicated. An aspiration of the glenohumeral synovial fluid is obtained prior to the arthrogram to rule out infection. Deltoid dehiscence and fatty infiltration and trophicity of the rotator cuff muscles may be evaluated using either of these imaging techniques.

Preoperative electromyography and nerve conduction testing are used to evaluate suspected plexus, suprascapular, or axillary nerve injury.

Failure of the deltoid to heal may be encountered during arthroplasty cases for failed rotator cuff repairs. A satisfactory outcome is associated with isolated smaller disruptions of the anterior deltoid, an intact acromion, and preservation of rotator cuff function. Poorer results occur with a prior lateral acromionectomy, involvement of the middle deltoid, a concomitant and poorly compensated massive rotator cuff tear, and duration of symptoms longer than 12 months. These patients must be educated about the likely events of prolonged postoperative immobilization and rehabilitation and about the unpredictability of the outcome.

The arthritic shoulder with soft-tissue deficiencies presents a formidable challenge for surgical reconstruction. Several options have been presented in the literature, including total shoulder replacement, humeral replacement alone (with various sizes and configurations of heads, with or without rotator cuff repair), reverse ball-and-socket arthroplasty, bipolar arthroplasty, arthrodesis, and superior reconstruction. When the patient has unrecoverable loss of the entire deltoid, arthrodesis is usually preferred; however, reconstruction of the deltoid with latissimus transfer is an option. As our experience with reverse shoulder arthroplasty increases, our indications for using this design rather than conventional shoulder arthroplasty continue to evolve. When joint replacement is selected, we now perform a reverse shoulder arthroplasty in patients with rotator cuff tear arthropathy and those with glenohumeral arthritis associated with irreparable rotator cuff tears. Hemiarthroplasty is performed occasionally, especially when the glenoid cannot support a glenosphere. Conventional shoulder arthroplasty in this population is reserved for patients with only the smallest easily reparable rotator cuff tears, which are often discovered intraoperatively and repaired through drill holes in the greater tuberosity. This chapter specifically focuses on the techniques of performing hemiarthroplasty in a soft-tissue deficient shoulder with biologic resurfacing of the glenoid and the coracoacromial arch, reconstructive options in the setting of subscapularis or deltoid insufficiency, and pearls for anchoring soft tissues to bone when an implant is already in place.

SURGERY

After intubation, the patient is placed in the beach-chair position. A beanbag under the affected scapula increases glenoid exposure. Lateralization of the patient’s body on the table aids in extension of the humerus during the procedure. A 10-minute iodine prep followed by painting with DuraPrep (3M, St. Paul, MN) with sterile orthopaedic draping technique is utilized. Appropriate preoperative prophylactic antibiotics are administered.

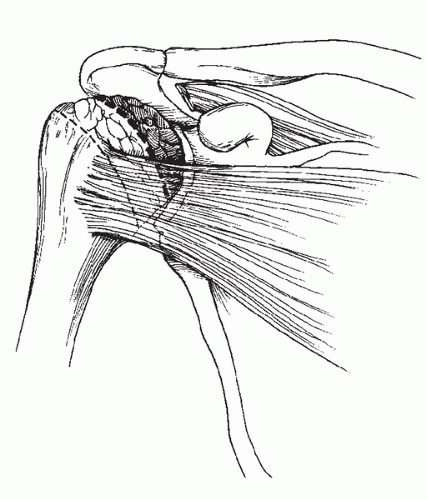

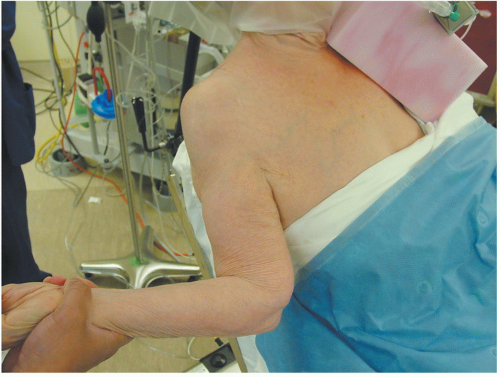

Preoperative examination of range of motion is assessed. Frequently, external rotation is significantly improved while the patient is anesthetized, indicating no fixed contracture. Excessive external rotation, especially compared to the contralateral side, typically indicates either partial or complete subscapularis deficiency (Fig. 38-1).

The standard deltopectoral approach that is described elsewhere is used most commonly, but the surgeon should also be familiar with the superior and more extensile approaches. Every attempt is made to preserve the coracoacromial arch; however, if the coracoacromial ligament must be divided for visualization purposes, it is

repaired at the completion of the case. In patients with marked medial glenoid erosion or chronic subscapularis tears, a portion of the conjoined tendon may be incised or the coracoid osteotomized to aid in visualization. If the coracoid is osteotomized, gentle retraction will avoid pressure on the brachial plexus. We routinely perform tenodesis of the long head of the biceps in arthroplasty cases, as this tendon has been shown to be a source of pain when left intact (3).

repaired at the completion of the case. In patients with marked medial glenoid erosion or chronic subscapularis tears, a portion of the conjoined tendon may be incised or the coracoid osteotomized to aid in visualization. If the coracoid is osteotomized, gentle retraction will avoid pressure on the brachial plexus. We routinely perform tenodesis of the long head of the biceps in arthroplasty cases, as this tendon has been shown to be a source of pain when left intact (3).

FIGURE 38-1 Examination under anesthesia demonstrates excessive external rotation consistent with subscapularis deficiency in this patient with arthritis and rotator cuff deficiency. |

Intact Subscapularis with Deficient Supraspinatus/Infraspinatus

The subscapularis is released sharply from the lesser tuberosity, beginning at the bicipital groove and taken medially. The circumflex vessels are ligated. Subperiosteal dissection around the humeral neck with the arm in maximum external rotation will protect the axillary nerve behind the elevated soft-tissue envelope. Tag sutures are placed in the subscapularis tendon. The capsule is further incised and the humeral head is dislocated.

The humeral osteotomy is performed to best restore the patient’s natural anatomy. Conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis with a thin, functionless cuff or rotator cuff tear arthropathy may require more retroversion (greater than 35 degrees) to center the humeral head under the acromion and to avoid postoperative anterosuperior instability. An aggressive humeral osteotomy is performed for patients with an intact subscapularis and deficient supraspinatus/infraspinatus superior complex (Fig. 38-2). The osteotomy follows a line extending

laterally 1 cm above the lateral flare of the greater tuberosity to a point medially where, with firm manual downward traction on the arm, the humeral neck meets the inferior aspect of the glenoid. This satisfies three objectives: (a) it leaves an osseous margin to which the distal ends of the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and subscapularis can be repaired; (b) it shortens the distance that the mobilized tendons must traverse; and (c) it centers the humeral head on the glenoid.

laterally 1 cm above the lateral flare of the greater tuberosity to a point medially where, with firm manual downward traction on the arm, the humeral neck meets the inferior aspect of the glenoid. This satisfies three objectives: (a) it leaves an osseous margin to which the distal ends of the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and subscapularis can be repaired; (b) it shortens the distance that the mobilized tendons must traverse; and (c) it centers the humeral head on the glenoid.

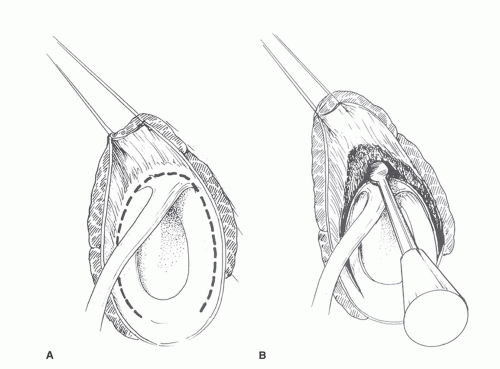

Extensive intra-articular and extra-articular releases may be required to mobilize the rotator cuff. A thorough bursectomy is performed. Intra-articular mobilization of the cuff tendons can be performed with a Cobb elevator carefully over the glenoid rim (Fig. 38-3A and B). Tag sutures are placed into the supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons. The coracohumeral ligament is then divided by pulling on the supraspinatus tendon sutures and cutting soft-tissue extensions to the base of the coracoid.

At a minimum, we prefer to remove any remaining glenoid cartilage with a curette and/or burr. When there is marked superior erosion of the glenoid, the burr is used to selectively remove bone from the inferior aspect of the glenoid until a superior shelf is created, thereby constructing a more concave surface for articulation with the humeral head. The glenoid may be reamed to a concentric surface and/or resurfaced as described later.

The humeral shaft is prepared by hand using implant-specific instrumentation by extending and externally rotating the shoulder. Hand preparation helps avoid shaft fracture and distal perforation of the humeral shaft. Reaming is finished when cortical resistance is first noted. The humerus is then broached. When the posterior glenoid is not eroded, the prosthesis should generally be retroverted more than usual (45 to 60 degrees) as described above. Once the final broach is fully seated, a metal trial head is placed and the trial reduction is performed. We typically use a smaller head, which creates less soft-tissue tension and permits easier rotator cuff closure and more motion. The repaired rotator cuff will provide static and dynamic stability for the smaller head.

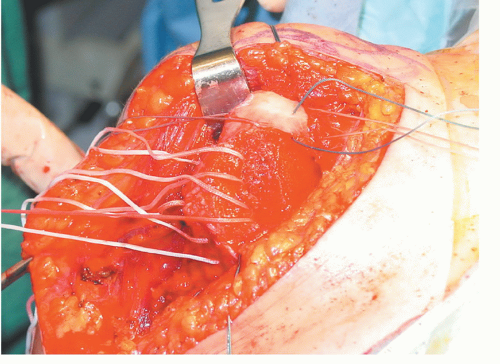

One millimeter cottony Dacron suture (Deknatel, a Teleflex company, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina) is placed into several 2-mm drill holes in the proximal humerus, approximately 1 cm from the humeral cut, to facilitate rotator cuff closure (Fig. 38-4). The holes for subscapularis closure are placed as superiorly

as possible. Using third-generation cementation technique, the humeral component is then cemented into the canal at the appropriate height and version. After the cement has cured, a final trial reduction is performed. The head is dialed such that the offset best matches the proximal humeral anatomy. The final selected humeral head is then impacted onto the clean humeral stem Morse taper.

as possible. Using third-generation cementation technique, the humeral component is then cemented into the canal at the appropriate height and version. After the cement has cured, a final trial reduction is performed. The head is dialed such that the offset best matches the proximal humeral anatomy. The final selected humeral head is then impacted onto the clean humeral stem Morse taper.

Rotator cuff closure begins posteriorly. The infraspinatus and supraspinatus are reapproximated first, using 1-mm cottony Dacron suture in a side-to-side fashion with a running baseball stitch. The previously placed cottony Dacron sutures in the greater tuberosity are then passed through the supraspinatus tendon and tied (Fig. 38-5A and B). If slight abduction is required for a tensionless repair, an abduction pillow is added to the postoperative sling for protection and support. The cottony Dacron sutures in the proximal portion of the lesser tuberosity are then passed through the subscapularis tendon and tied, bringing the tendon superiorly to allow closure of the rotator interval (Fig. 38-6A and B). The rotator interval is reapproximated with a running baseball stitch using a no. 2 Ethibond suture (Ethicon, Inc., Somerville, NJ) (Fig. 38-7). The deltopectoral interval is closed with a running no. 2 Vicryl suture (Ethicon). A drain is placed under the deltopectoral interval.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree