Total Shoulder Replacement: Managing Bone Deficiencies

Robert H. Cofield

John W. Sperling

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

For total shoulder arthroplasty, there are three major indications. One relates to patient symptomatology and a second to surgical pathology. Patients who might be considered for total shoulder arthroplasty must have sufficient pain and functional limitations to justify the procedure. Also there must be loss of glenohumeral cartilage or severe distortion of the articular surfaces that would not respond to a lesser procedure. When there are bone deficiencies, the procedure is more difficult, and the surgical prognosis may not be quite so good, so the indications must be sufficient.

The third indication is the potential for a high degree of improvement by surgical treatment. The patients discussed in this chapter have, in addition to the above pathologic changes, some degree of deficiency of bone in the glenoid or in the proximal humerus. Some have such severe bone loss that total shoulder replacement might not be possible. This sometimes occurs in scapular dysplasia, in patients with ancient Erb palsy, or, perhaps most commonly, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis who have had severe central resorption. In this last condition, one might consider placement of a humeral head prosthesis alone (l).

There are components of shoulder disease that are relative or absolute contraindications to surgery, such as active or recent shoulder joint infection, a neurologic condition resulting in severe weakness of the deltoid and rotator cuff; a motion disorder that would preclude rotator cuff healing; and severe, uncorrectable glenohumeral instability. A contraindication unrelated to shoulder pathology is substance abuse, which could preclude successful participation during the recovery period. These considerations are the same for patients with and without concomitant bone deficiency who are being considered for total joint arthroplasty.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

Patients being evaluated for total shoulder arthroplasty should have the usual history and physical examination supplemented by standard radiographs. A patient who has glenohumeral arthritis with concomitant humeral and glenoid bone deficiencies has many of the same presenting complaints as a patient with cartilage loss without these deficiencies. There is usually a long history of gradually increasing shoulder pain, initially made worse with activity and finally occurring even in a position of rest. By the time the point of needing an arthroplasty has been reached, the patient is often being awakened from a sound sleep with incapacitating pain, frequently needing to sleep sitting up for pain relief. Some patients become dependent on narcotic medication because of the severe and incapacitating shoulder pain.

Examination often reveals a very tentative patient, anxious that the shoulder not be moved or touched. If there is significant central bone loss, glenoid wear, or humeral head deficiency, the lateral border of the acromion or coracoid process may be quite prominent. Significant posterior bone erosion often makes the coracoid

prominent with a bulge posteriorly along the joint line compatible with a subluxation of the humeral head. As with most other patients with glenohumeral arthritis, there is often significant joint-line tenderness and a hard, grating crepitus on gentle rotation of the glenohumeral joint. Range of motion is often significantly restricted in all degrees tested because of a combination of joint incongruity, soft-tissue stiffness, and voluntary restriction of motion due to pain. While it is difficult to test active range of motion because of the significant pain, it is often possible to get a general feel for muscle strength, particularly of the rotator cuff. Weakness of external rotation can be assessed by asking the patient to stand with the arm at the side and externally rotate it as the examiner’s hand provides some resistance. In a patient with glenohumeral arthritis, this active contraction of the external rotators against resistance centralizes the humeral head in the glenoid and augments the deep crepitus, and a ratcheting type of movement occurs.

prominent with a bulge posteriorly along the joint line compatible with a subluxation of the humeral head. As with most other patients with glenohumeral arthritis, there is often significant joint-line tenderness and a hard, grating crepitus on gentle rotation of the glenohumeral joint. Range of motion is often significantly restricted in all degrees tested because of a combination of joint incongruity, soft-tissue stiffness, and voluntary restriction of motion due to pain. While it is difficult to test active range of motion because of the significant pain, it is often possible to get a general feel for muscle strength, particularly of the rotator cuff. Weakness of external rotation can be assessed by asking the patient to stand with the arm at the side and externally rotate it as the examiner’s hand provides some resistance. In a patient with glenohumeral arthritis, this active contraction of the external rotators against resistance centralizes the humeral head in the glenoid and augments the deep crepitus, and a ratcheting type of movement occurs.

Plain films typically include a 40-degree posterior oblique view in internal and external rotation plus an axillary radiograph. To better understand bony positioning of the tuberosities, a scapular lateral view is often helpful, in addition to the above three views. If the bony deformity or deficiency cannot be completely assessed with plain radiographs, narrow-cut (3 mm) computed tomography (CT) scanning of the shoulder joint should provide any additional information necessary for preoperative planning. In some complex situations, such as old comminuted fractures with malunion, 3-D reconstruction of the CT image may prove helpful; however, this is seldom required.

Autogenous bone graft is usually obtained from the humeral head. If additional autogenous bone graft will be needed, it will have to be determined whether graft material from the anterior iliac crest will be sufficient or whether a bone graft must be taken from the posterior portion of the ilium before approaching the shoulder joint (1, 2). If allograft material is needed, one would contact the bone bank to ensure that material is available. If bulk allograft is needed, it is helpful to have a radiograph of the opposite, uninvolved shoulder and a radiograph of the available bulk allograft to ensure appropriate size matching.

Occasionally, a custom implant is necessary, particularly for larger humeral deficiencies but also for glenoid bone deficiency. For the former, it is helpful to have a radiograph of the opposite, uninvolved humerus in addition to a full-length radiograph of the involved humerus, both with magnification markers on the film, to construct or obtain the custom implant. Templates are available for many shoulder joint replacements, and in difficult reconstructive settings, it is probably wise to use them as an adjunct to preoperative planning.

In addition, it should be emphasized that soft-tissue reconstruction is an integral part of total shoulder arthroplasty with or without bony deficiency (3). The best results are achieved when the deltoid is intact and functioning. It is important to have an understanding of the rotator cuff and capsule pathology associated with the various diseases for which this operation is performed (4). In osteoarthritis, there is seldom significant rotator cuff tearing. If present, it is usually superior in location and small to medium in size. In rheumatoid arthritis, anything can exist. The rotator cuff can be normal or near normal, or a massive tear can be present. Typically, it is thinned superiorly and may have a medium to large tear that is superior in location rather than anterosuperior. In old trauma, bony deformities predominate with associated rotator cuff stretching, tearing, or contracture, dictated by the position of the tuberosity. In osteonecrosis, the rotator cuff is almost always intact but may be involved with an inflammatory process that renders the tissues somewhat tighter and stiffer than usual. In rotator cuff tear arthropathy, there is always a massive tear involving the supraspinatus, the infraspinatus, and often a portion of the subscapularis. In surgery for revision of a previously placed prosthesis, in addition to bone, rotator cuff, and capsule deficiencies and possible neurologic impairment, the surgeon must address scar tissue that infiltrates the remaining tissues.

An issue in preoperative planning is glenohumeral stability. When the glenohumeral joint is stable, a small amount of bone deficiency can often be tolerated and accepted as a part of the reconstructive process. When instability is present, the bone deficiency will need to be more fully corrected to ensure postoperative stability of the artificial joint. This situation most commonly arises in osteoarthritis, because the posterior glenoid wear may be associated with substantial posterior humeral subluxation, requiring the bony deficiency to be more fully corrected than if subluxation is not present.

Last, the degree of glenohumeral stiffness must be carefully evaluated. This may be related to incongruity of the joint surfaces but often depends on the condition of the shoulder capsule and surrounding rotator cuff. To have a mobile joint after surgery, these joint contractures usually have to be released. When there is bone deficiency, more exposure is usually needed to correct it, and there is more extensive tissue release in the reconstructive procedure. The latter includes release of the inferior shoulder capsule, release or lengthening of the anterior structures, and perhaps release of the superior and posterior aspects of the shoulder capsule, depending on the preexisting structural abnormalities.

Thus, a thorough preoperative analysis of the pathologic anatomy is essential to the reconstructive procedure. Not only must one have adequate imaging to define the alterations in bone quality, quantity, and position, but one must also have a good understanding of the condition of the surrounding musculature and the shoulder capsule. If concerned about these structures, an MRI will be helpful. In addition, it is important to consider the possibility of neurologic compromise and the various patient selection factors. If there has been previous surgery, one also must rule out the possibility of occult or low-grade infection with hematologic studies, aspiration arthrography, or bone and indium-labeled scans.

If a history of previous trauma or physical examination findings suggests deficiency of muscle groups such as the deltoid, more thorough evaluation of neurologic status by a preoperative electromyogram may be considered.

Some patients with a neuropathic glenohumeral joint have extensive humeral or glenoid bone loss and destruction. Fortunately, many of these patients do not have pain in the involved joint despite extensive bony destruction. Radiographic evidence of a neuropathic joint should prompt the clinician to do a careful peripheral neurologic examination and consider imaging studies of the cervical spine, because a cervical spine syrinx is a common pathologic entity leading to a neuropathic shoulder.

SURGERY

When doing additional work on the glenoid, five “presteps” should be considered: extended exposure and extended arthrotomy, ample humeral bone removal, capsule releases, and the availability of special retractors. The patient is placed in a beach-chair position, semisitting, with the head secured to the operating table. An interscalene block is given, but general anesthesia and endotracheal intubation are usually required, particularly with a lengthy operation as may occur if there is extensive bone loss. The arm is draped free. For implantation of the humeral component, hyperextension of the arm is often needed. In contrast, for glenoid exposure, resting the arm on a draped Mayo stand will help keep the proximal humerus retracted posteriorly, giving better access.

During total shoulder arthroplasty, one of the most difficult aspects is exposure of the glenoid. When bone deficiency exists in the glenoid, the exposure must be somewhat fuller, and when deficiency exists in the humerus, it may be necessary to extend the incision distally.

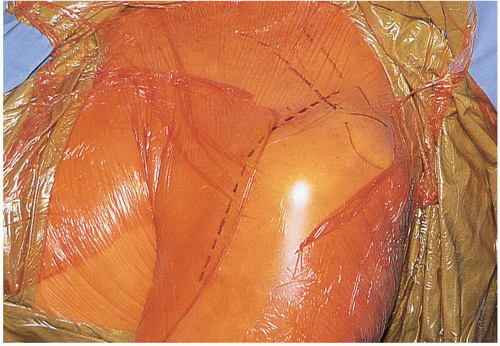

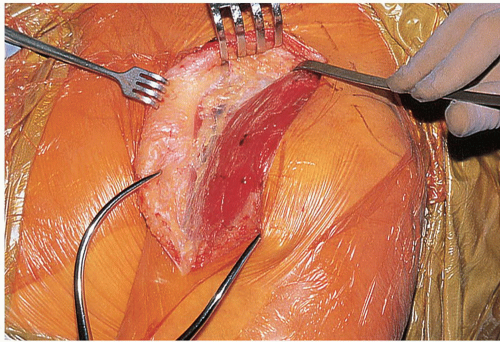

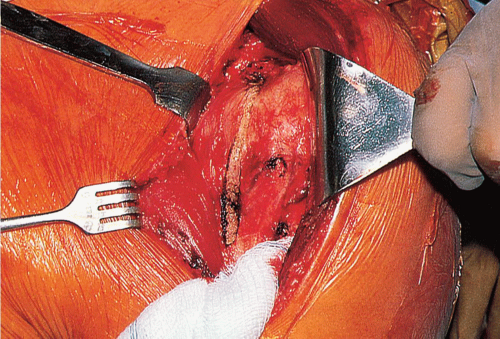

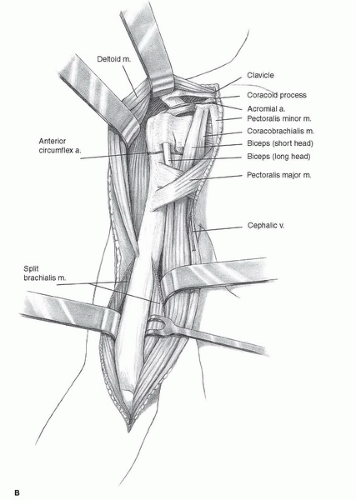

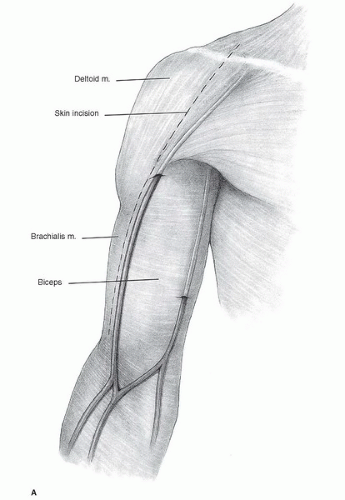

The exposure begins with the skin incision. I believe it is helpful to comment on certain aspects of exposure in the presence of glenoid and humeral bone deficiencies. The most useful incision is on the anterior aspect of the shoulder, extending from approximately 1 cm medial to the distal aspect of the clavicle, downward to the anterior aspect of the insertion of the deltoid muscle on the humerus (Fig. 37-1). This skin incision is directly over the tissues involved in most of the surgical procedure, preventing the need for retracting the skin incision further during the various surgical manipulations. It is necessary to raise a small medial flap (Fig. 37-2) to identify the deltopectoral interval and then to retract the deltoid laterally (Fig. 37-3). One must open the entire length of the deltopectoral interval from the clavicle to the insertion of the deltoid on the humerus, and, when the deltoid is somewhat stiff, it is helpful to elevate the anterior portion of the deltoid insertion in continuity with the distally extending periosteum. The fascia lateral to the conjoint tendon is then incised, and the conjoint tendon is retracted medially, affording the opportunity to free the subscapularis from contracted bursa or related scar. The subacromial and subdeltoid spaces are then fully freed of scar tissue to further facilitate the deeper exposure.

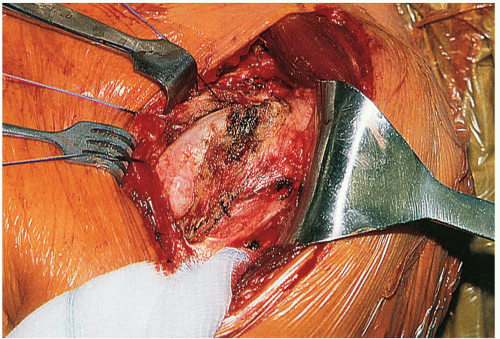

Ample exposure of the glenoid is likely to be desired, and it is useful to have a long arthrotomy incision extending from the supraglenoid tubercle (just anterior to the attachment of the long head of the biceps tendon), along the anterior aspect of the intra-articular portion of the long head of the biceps, and then curving distally at the capsular attachment on the humerus (Fig. 37-4). In the lower portion of the subscapularis, the branches of the anterior humeral circumflex vessels are coagulated, and the incision is directed onto the humeral neck. One can then, by externally rotating the humerus, release most of the inferior shoulder capsule from the humeral neck. One then has an arthrotomy (if this is a left shoulder) extending from the 11 o’clock position to the 6 o’clock or 5 o’clock position.

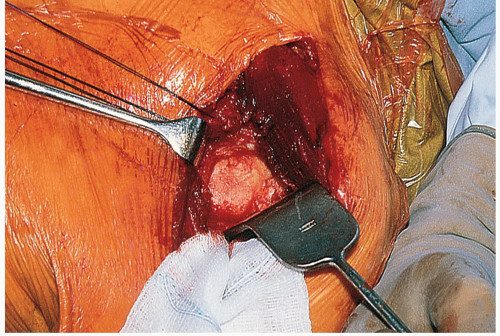

Following removal of humeral osteophytes and excessive humeral metaphyseal bone, and following osteotomy of the humeral head, there is ample exposure of the glenoid (Fig. 37-5). If the joint is still too tight, intra-articular scar can be excised, and a portion of the superior or posterior capsule can be incised at the glenoid rim. This exposure should allow one to easily address central glenoid wear and peripheral, asymmetric glenoid wear such as that typically seen in osteoarthritis. There are rare segmental glenoid deficiencies that may not be addressed by this approach.

FIGURE 37-5 Glenoid exposure. A ring retractor holds the remaining humeral head posteriorly, and a knee retractor holds the subscapularis anteriorly. The entire glenoid face is exposed. |

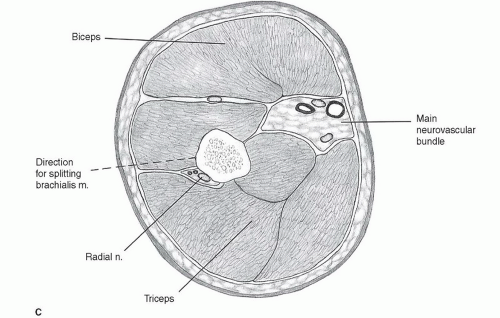

If there is a deficiency of the proximal humerus, it may be necessary to extend the skin incision distally along the anterolateral aspect of the arm (Fig. 37-6). The lateral portion of the brachialis muscle is incised, and the tissues are elevated medially and laterally to expose distal, uninvolved humeral bone (6). One must take great care to protect the radial nerve in the lateral aspect of the wound.

Glenoid Bone Deficiencies

It is very important to consider bone quality (Tables 37-1 and 37-2). Typically, there will be a glenoid subchondral plate that is 1 to 2 mm thick, and beneath this will be a rather firm, cancellous bone surrounded by a thin, cortical shell. However, the bone quality varies considerably. The bone may be pockmarked with cysts, there may be severe osteopenia, or, perhaps more typically, the bone may be very sclerotic, extending throughout the glenoid neck, compromising fixation capabilities. Many surgeons consistently use methylmethacrylate bone cement as an adjunct to glenoid component fixation; others turn in some situations toward a tissue-ingrowth component. The ideal bone for methylmethacrylate fixation is also the ideal bone for placement of a tissueingrowth component. When the bone is very osteoporotic, one leans toward the use of bone cement as an adjunct to fixation, but the fixation will be less secure than if the bone was of typical density. When the bone is extremely sclerotic, fixation is impaired with the use of bone cement or with the use of a tissue-ingrowth component. Some surgeons might lean more toward the use of a tissue-ingrowth component in this setting, but that is not always better.

When assessing the remaining glenoid bone, it is important to consider the glenoid bone surface, its size, and its orientation. Often, variation in size can be addressed by using a component of a corresponding size, that is, using a smaller component for a smaller glenoid and so forth. It is important to determine the length of the glenoid neck to ascertain whether there will be enough remaining bone to secure the keel or the columns of the various types of glenoid components. It is helpful to have 2 cm of depth to the glenoid neck. When it becomes less than this, compromise of fixation occurs. At a depth of approximately 1.5 cm, fixation will probably still be secure; at a depth of 1 cm, fixation will be significantly compromised. It is probably true that the depth of the glenoid neck can be slightly less when one uses a columned component than that for a component with a keel, because the columns can penetrate into the junction of the glenoid neck with the body of the scapula and gain some purchase. It is very difficult to accomplish this with the keel-like component that requires methyl-methacrylate bone cement for fixation.

Central Bone Loss

There are two types of central bone loss of the glenoid. The first and probably most significant occurs when the entire glenoid face resorbs medially (Fig. 37-7). The glenoid is shaped like a funnel, and, as the bone is worn medially, substantially less bone remains to allow secure fixation of the component. This situation most commonly arises in rheumatoid arthritis (Fig. 37-8). When it is identified on preoperative radiographs and intraoperatively, it may be prudent to place a centering hole to ascertain the depth of the glenoid neck (Fig. 37-9). If 1 cm or less of glenoid neck remains, one might consider recontouring the remaining glenoid surface with a burr or reamer and placing a humeral head component without a glenoid prosthesis (Fig. 37-10). In this situation, pain relief is more likely with a humeral head replacement alone than it would be with a total shoulder arthroplasty with an insecurely fixed glenoid component (9).

FIGURE 37-6 A: The line of skin incision for distal extension of total shoulder arthroplasty exposure (5). The length of the distal extension is modified according to the exposure needed. |

TABLE 37-1 Classification of Glenoid Bone Deficiencies | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree