Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic, systemic, inflammatory condition of unknown etiology affecting 1% to 2% of the population.

It affects females two to three times as frequently as males, and the incidence increases with age, typically peaking between 35 and 50 years of age.

Peripheral joints are often affected in a symmetric pattern.

The elbow is affected in about 20% to 70% of patients with RA, with a wide spectrum of severity.

Ninety percent of these patients also have hand and wrist involvement and 80% also have shoulder involvement.

Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA) is diagnosed based on the presence of arthritis, synovitis, or both in at least one joint lasting for more than 6 weeks in an individual younger than 16 years old.

Compared with adult-onset RA, JRA is complicated by severe osseous destruction, deformity, and soft tissue contractures.

The cause of RA is unknown.

Infectious etiologies have been proposed, but no microorganism has been proven to be causative.

Genetic and twin studies have demonstrated that a genetic predisposition clearly exists, and the disease is also associated with autoimmune phenomena.

In patients with RA, numerous cell types, including B lymphocytes, CD4 T cells, mononuclear phagocytes, neutrophils, fibroblasts, and osteoclasts, have been shown to produce abnormally high levels of various cytokines, chemokines, and other inflammatory mediators.

The result is inflammatory-mediated proliferation of synovial tissue, leading to soft tissue and finally bony destruction.

Overall, the disease progresses from predominantly soft tissue (synovial) inflammation to articular cartilage damage and ultimately subchondral and periarticular bone destruction.

Manifestations of RA are initiated by synovitis and synovial hyperplasia resulting in pannus formation. This correlates with a boggy, inflamed elbow that is painful and with limited range of motion.

Synovial proliferation coupled with joint capsule distention may produce a compressive neuropathy with pain, paresthesias, or weakness in the ulnar or radial nerve distributions, or both.

Degeneration may progress to ligamentous erosion or disruption, or both. Clinically, the patient experiences progressive instability as ligamentous integrity is compromised.

It may affect the annular ligament and produce radial head instability with anterior displacement.

Eventually, the medial and lateral collateral ligament complexes may be disrupted, thus causing further instability.

Prolonged synovitis leads to erosion of the cartilage followed by subchondral cyst formation and marginal joint erosions; the result is end-stage arthritis.

End-stage disease is marked by severe damage to subchondral bone and gross joint instability. At this stage, patients typically have a painful, weak, and functionally unstable elbow.

Patients typically describe a history of a swollen, tender, and warm elbow with diminished and painful range of motion.

This may be accompanied by a report of progressively declining function, constitutional complaints, and often polyarticular involvement.

In early stages of the disease, the elbow may appear more boggy, with impressive soft tissue swelling and erythema about the elbow.

As the disease progresses to later stages, soft tissue swelling may become less prominent and the elbow becomes more stiff and painful.

Elbows affected by JRA occur in younger patients as compared with elbows affected by RA.

Patients with JRA also have stiffer elbows and therefore typically do not have instability.

Often, JRA patients have more joints affected by the rheumatoid process, but they also demonstrate a greater tolerance for pain.

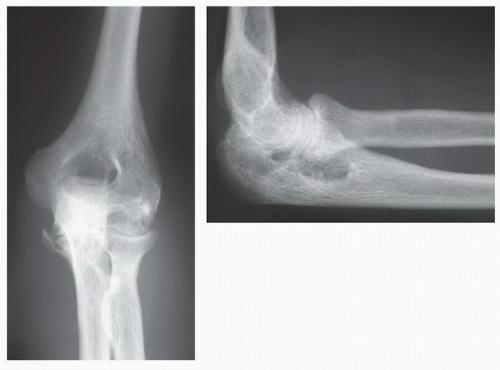

Anteroposterior (AP) and lateral radiographs of the elbow are obtained to assess the degree of rheumatoid involvement and for preoperative planning (FIG 1). No further studies are typically required.

Although several classification systems have been proposed, the most commonly used is the Mayo Radiographic Classification System (Table 1).8

It allows monitoring of disease progression and often correlates well with clinical examination findings and patients’ functional limitations.

The grading system is based on bone quality, joint space, and bony architecture and delineates four grades of progression in order of increasing severity.

Calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease

Osteoarthritis

Polymyalgia rheumatica

Psoriatic arthritis

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Fibromyalgia

Optimal care of the patient with RA requires a team-based approach between the orthopaedic surgeon, rheumatologist, and physical therapists to coordinate the full gamut of nonsurgical and surgical treatment options.

The medical management of RA continues to evolve and is highly effective.

Medical therapy includes classes of drugs known as diseasemodifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), immunomodulators, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors, as well as other drugs targeting systemic inflammation. These medications may be given alone or as part of combination therapy.

DMARDs include medications such as methotrexate, leflunomide, hydroxychloroquine, and sulfasalazine.

Immunomodulators such as azathioprine and cyclosporine target the pathologic immune system but may also increase susceptibility to infection.

Anti-TNF-alpha agents can reduce pain, morning stiffness, and swollen joints by inhibiting an inflammatory cytokine called TNF-alpha. Examples of these drugs include etanercept, infliximab, adalimumab, golimumab, and certolizuman. These medications can also increase the risk of developing severe infection.

Other medications which target inflammation include anakinra, abatacept, rituximab, tocilizumab, and tofacitinib.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and steroids, such as prednisone, may be prescribed to reduce symptoms of RA as well.

Judicious use of intra-articular steroid injections also plays a role in symptom management.

The importance of early referral to a rheumatologist for medical management cannot be overemphasized. Aggressive management of the synovitis can limit or delay the onset and severity of joint involvement. The most reliable and effective responses to antirheumatic medications are observed with therapy initiated in the early stages of the disease.

The goal of physical therapy is to encourage range of motion, functional strength, and maintenance of activities of daily living. This is accomplished by activity modification, rest, ice, and gentle exercise.

The primary objective of nonoperative management of the rheumatoid elbow is to minimize soft tissue swelling and to optimize range of motion, as preoperative range of motion is often predictive of postoperative total arc of motion after arthroscopic synovectomy as well as total elbow arthroplasty.

Surgical management of the rheumatoid elbow primarily consists of synovectomy and total elbow arthroplasty.

For early disease states, excellent clinical results may be achieved with synovectomy performed using open or arthroscopic techniques.

The goal of synovectomy is to relieve pain and swelling. Although this procedure has not necessarily been shown to alter the natural history of the disease, it reliably produces symptomatic relief for 5 or more years in the majority of cases performed on elbows in the early stages of the disease process.6

The arthroscopic approach is advantageous over the more traditional open approach in that it is less invasive, is associated with less perioperative morbidity, and also allows predictable access to the sacciform recess. When open synovectomy is performed, the radial head must be excised to access and completely débride the diseased synovial tissue that exists in this region.

Open synovectomy has traditionally been accompanied by radial head excision due to1 ubiquitous radiocapitellar and proximal radioulnar joint articular destruction and2 the need to surgically expose the sacciform recess for the requisite complete synovectomy.

It has been shown that routine radial head excision may predispose patients with RA to increasing valgus elbow instability due to the loss of the stabilizing effect of the radial head (particularly if the medial collateral ligament is adversely affected by the rheumatoid process).9

Because the entire synovial proliferation around the radial neck can be accessed arthroscopically, a combined arthroscopic radial head excision is performed only in patients with stable elbows and preoperative elbow symptoms worsened with forearm rotation. Otherwise, a complete arthroscopic synovectomy is performed without excising the radial head.

In addition, the minimally invasive nature of an arthroscopic approach yields the potential advantages of less pain, faster recovery with earlier range of motion, and a lower rate of infection compared with an open procedure.

Table 1 Mayo Radiographic Classification System

Grade

Radiographic Appearance

Description

Implications

I

Synovitis in a normal-appearing joint with mild to moderate osteopenia

Often correlates with impressive soft tissue swelling on clinical examination

II

Loss of joint space but maintenance of the subchondral architecture

Varying degrees of soft tissue swelling are present.

III

Marked by complete loss of joint space

The synovitis has “burned out” and the elbow is typically more stiff.

IIIA

Bony architecture is maintained

IIIB

Associated bone loss

IV

Severe bony destruction

Patients often have severe pain and functional limitations; functional instability may also be present if the joint’s bony architecture is destroyed.

V

Presence of bony ankylosis of the ulnohumeral joint

Most commonly seen with JRA

Adapted from Morrey BF, Adams RA. Semiconstrained arthroplasty for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1992;74(4): 479-490; Connor PM, Morrey BF. Total elbow arthroplasty in patients who have juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1998;80(5):678-688.

An arthroscopic anterior capsular release may be performed at the time of the arthroscopic synovectomy to improve elbow extension. A posterior olecranon plasty may also be performed to reestablish normal concavity of the olecranon fossa.

Posteromedial capsule release should be avoided to prevent the risk of iatrogenic ulnar nerve injury. If an elbow requires a release of the posterior capsule to regain elbow flexion (typically those with 100 degrees or less of preoperative flexion), then the surgeon should perform an open ulnar nerve decompression and subcutaneous transposition followed by complete posterior capsule release (including the posteromedial band of the medial collateral ligament).

This procedure is indicated for advanced (grade III or IV) RA of the elbow in patients with significant pain and limitations in activities of daily living.

Absolute contraindications include active infection, upper extremity paralysis, and a patient’s refusal or inability to abide by postoperative activity restrictions.

Relative contraindications include presence of infection at a remote site and a history of infected elbow or elbow prosthesis.

AP and lateral radiographs of the elbow are reviewed to assess humeral bow and medullary canal diameter as well as angulation and diameter of the ulnar medullary canal.

Preoperative radiographic templates may be helpful to assess preoperative radiographic magnification.

In particular for JRA patients, the canal width may be very small, and therefore the surgeon must ensure that appropriately sized implants as well as intramedullary guidewires and reamers are available.

If an ipsilateral total shoulder arthroplasty has been performed or is anticipated, a humeral cement restrictor should be used. A 4-inch humeral implant may also be considered; however, shorter, recently introduced humeral components for total shoulder arthroplasty can typically be placed even in the presence of a 6-inch humeral stem. Overlapping cement mantles and/or a short cement gap between the humeral stems of the shoulder and elbow prostheses should be avoided to reduce the risk of subsequent periprosthetic fracture.

Preoperative limitations in forearm rotation may be due in part to ipsilateral distal radioulnar joint pathology. Thus, radiographs should also be obtained of the ipsilateral shoulder and wrist.

Implant options have traditionally been classified as linked (semiconstrained) or unlinked.

These terms are being used with decreasing frequency, however, as some unlinked implant designs have been developed that have precisely contoured components that create a degree of constraint.

Linked, semiconstrained implants inherently have about 7 degrees of varus-valgus and 7 degrees of axial rotation, “play,” whereas unconstrained implants typically refer to unlinked, resurfacing components.

The stability of unconstrained implants depends on soft tissue and ligamentous integrity. Such tissues may be destroyed by the rheumatoid inflammatory process or surgically released with semiconstrained implants without compromising stability.

Although no prospective comparisons between linked (semiconstrained) and unlinked implants have yet been performed, studies have generally reported improved survivorship with a semiconstrained design.7

The semiconstrained design is preferred because it is equally effective in pain relief and in improving range of motion and function while preserving stability without an observed increase in aseptic loosening.7

The Techniques section describes implantation of a linked, semiconstrained implant.

Polyethylene bushing wear is a challenging issue which has been implicated as a limiting factor in long-term implant durability following total elbow arthroplasty.2,5,10 Polyethylene wear has been reported after total elbow arthroplasty with multiple implant designs.5,10 Osteolysis and loosening from particle-induced bushing wear is an important concern when considering mid- to long-term survivability of the implants, and this is of particular importance for younger patients undergoing total elbow arthroplasty, especially for posttraumatic conditions. Newer bearing designs have recently been created to address the potential issues related to polyethylene wear, including increasing the amount of polyethylene in the bushing as well as designs with conforming polyethylene and metallic-bearing surfaces. The implant described in the Techniques section uses a novel vitamin E highly cross-linked ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene bearing to prevent metal-to-metal contact and is designed to have improved polyethylene wear characteristics.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree