Torn Meniscus

Jess H. Lonner

Eric B. Smith

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Meniscal tears can be acute or chronic degenerative tears. Acute meniscus tears most commonly occur in patients between the second and fourth decades of life. With an acute meniscal tear, a patient will report a rotational or “twisting” injury to the flexed knee that often results in an audible “pop” with concurrent localized sharp pain. The pain may be of limited severity such that the individual is able to return to activity relatively soon after the injury. The patient may develop an effusion with mild to moderate knee pain. Patients may also describe mechanical symptoms of the knee catching or locking, resulting in difficulties with flexion and extension. With large tears, the knee can become locked in flexion and the patient may be unable to straighten the knee. Severe pain may occur with squatting or pivoting.

Chronic meniscus tears generally occur in older patients and are the result of degenerative changes in the meniscus that are typical of aging. Patients with such tears will have insidious onset of knee pain and effusion. There is often no discrete history of trauma. The pain is exacerbated by activity and improved with rest. A knee effusion may be present and can vary in size based on the patient’s recent activity level.

CLINICAL POINTS

Acute meniscus tears are more common in younger adults.

Chronic meniscus tears are often more frequent in older adults.

The nature of pain is variable though it is typically related to activity and localized to the respective side of the knee.

Effusion may be present.

PHYSICAL FINDINGS

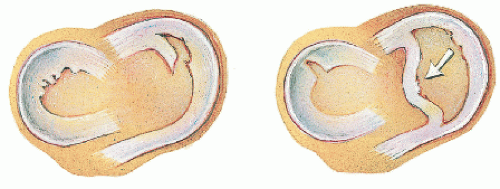

Patients with acute traumatic meniscus tears will have tenderness to palpation along the joint line in the area of the tear. Thus, those with medial meniscus tears will have medial joint line tenderness, and those with lateral tears will have lateral joint line tenderness. A knee effusion is also likely to be present. The McMurray test, which is performed by extending a flexed knee while exerting an internal or external rotation force on the tibia, may elicit pain and a pop or click; this pop/click is the result of the torn edge of the meniscus being caught between the tibia plateau and femoral condyle as the knee moves from flexion to extension.

The Apley grind test can also be performed to assess for meniscal pathology. This test is performed with the patient lying prone on the examination table with the knee flexed to 90 degrees. Downward pressure is applied to the foot and leg while rotating, flexing, and extending the knee. A positive test will elicit pain and popping along the joint line.

Patients with chronic, degenerative meniscus tears may have fewer positive physical findings. Anatomically, degenerative tears involve more meniscal fraying and fissuring; such tears do not often have large pieces of torn meniscus in the knee joint space that can produce mechanical symptoms. Therefore, tests such as the McMurray and Apley may not be positive. The absence of such positive provocative tests does not rule out chronic meniscus tear. Patients will consistently demonstrate medial or lateral joint line tenderness. Patients with chronic tears will also often have some degree of coexisting degenerative joint disease (DJD).

STUDIES (LABS, X-RAYS)

Initial studies for any patient with an acute knee injury, pain, and an effusion include anteroposterior (AP) and lateral plain x-rays of the knee to look for fractures. If these studies are negative and the diagnosis of meniscus tear is suspected based on history and physical exam, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is warranted, as this modality is highly sensitive and specific; MRI has been demonstrated to be 80% to 90% accurate in diagnosing such tears1 (Figs. 19-1,19-2,19-3).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree