Tibial Shaft Fractures: Intramedullary Nailing

Robert A. Winquist

Kenneth Johnson*

Donald A. Wiss

*deceased.

Indications/Contraindications

Intramedullary nailing of tibial shaft fractures gained widespread acceptance with the introduction of nails with locking capabilities. A large body of literature supports the use of intramedullary nailing in both closed and open fractures. Nevertheless, controversies abound with regard to the role of reaming in high-energy and open fractures, the timing of surgery, and its application in very proximal and distal fractures. Because the spectrum of injuries to the tibia is so broad, no single method of treatment is applicable to all fractures.

Nonoperative treatment with casts or braces, while minimizing the risk of infection, often results in unacceptable shortening, malrotation, or angulation in high-energy injuries. Although the better choice for improving alignment and function, operative treatment is associated with increased risks of infection and nonunion. Recent advantages in plate osteosynthesis with peri-articular and locked plating have lowered complication rates but are less applicable for diaphyseal tibial fractures. Another alternative, stabilization with an external fixator, while decreasing risk of infection, is associated with poor patient acceptance, repeated surgeries, and angulation after fixator removal. To improve overall outcome, locked intramedullary nailing for unstable, displaced, closed and open, tibial fractures is a useful treatment alternative.

Intramedullary nailing of high-energy tibial fractures, while mechanically sound, may be biologically less attractive. Studies on reamed intramedullary nails have shown substantial endosteal vascular damage incurred by multiple passes of the reamer, thermal necrosis of bone, impaction of the haversian canals with the products of reaming, and an increased risk of infection. Nevertheless, the advantages of intramedullary reaming

include placement of a larger nail and screws, which improves alignment and reduces hardware failure. Despite the risks of reaming, the literature strongly supports the use of a reamed intramedullary nail as the implant of choice for most unstable, closed, tibial-shaft fractures. However, multiple studies also support the use of both reamed and nonreamed nails for Gustillo grade I, II, and IIIA open tibial fractures. For grade IIIB and IIIC fractures, we favor temporary or definitive external fixation or on occasion a nonreamed, small-diameter, statically locked nail.

include placement of a larger nail and screws, which improves alignment and reduces hardware failure. Despite the risks of reaming, the literature strongly supports the use of a reamed intramedullary nail as the implant of choice for most unstable, closed, tibial-shaft fractures. However, multiple studies also support the use of both reamed and nonreamed nails for Gustillo grade I, II, and IIIA open tibial fractures. For grade IIIB and IIIC fractures, we favor temporary or definitive external fixation or on occasion a nonreamed, small-diameter, statically locked nail.

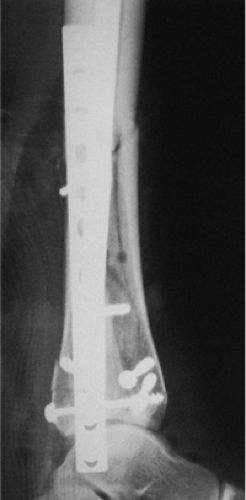

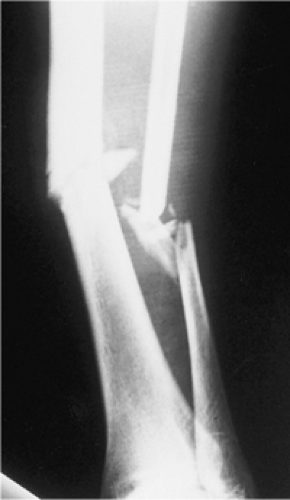

Intramedullary stabilization of the tibia is indicated in patients with multiple injuries; an ipsilateral fracture of the femur, ankle, or foot; a vascular injury; compartment syndrome; and bilateral fractures. Fractures located in the middle two thirds of the tibia that are amenable to nailing include transverse, short oblique, spiral, comminuted, and segmental fractures (Figs. 29.1,29.2,29.3,29.4). Indications for nailing may extend proximally or distally, particularly in segmental fractures. Unstable fractures with high-grade soft-tissue injury, whether closed or open, require operative stabilization. Unacceptable fracture position after closed reduction and casting is also an indication for nailing. Those with shortening more than 1.5 to 2.0 cm and angulation in excess of 5 degrees of varus or valgus or 10 degrees of anterior or posterior angulation may be candidates for intramedullary nailing. Tibial fractures with an intact fibula should only be stabilized if the tibial fracture is displaced or in angulation (Figs. 29.5 and 29.6). For a minimally or nondisplaced oblique or spiral fracture, nonoperative treatment is satisfactory. Nearly all open fractures require stabilization to allow improved management of the soft tissue.

Contraindications to nailing include immature patients with open epiphyses and a tibial tubercle apophysis. Patients with damage to the apophysis may experience hyperextension. A lateral radiograph should be carefully inspected because very small medullary canals may present a hazard during nailing (Fig. 29.7). If the surgeon elects to proceed with nailing in patients with small canals, a small-diameter Ender nail can be placed, or 5-mm-diameter reamers must be used to start a careful reaming process that will not burn the bone. A tourniquet should not be used for reaming in any patient during tibial nailing.

Figure 29.3. Postoperative AP radiograph showing lag screws for ankle fracture and interlocking nail for tibial fracture. |

Figure 29.5. Tibial fracture with intact fibula. Varus angulation and translation indicate operative treatment. |

Figure 29.7. Lateral radiograph demonstrating an extremely small medullary canal. Reaming should be avoided or carried out with very small reamers (starting at 5 mm). |

Another contraindication is infection. Nailing in an area of infection carries a high risk for chronic osteomyelitis and decreased union. Infected injuries are best handled with debridement and external fixators.

Preoperative Planning

In a careful physical examination of the patient, the physician should look for other injuries. Examination for neurovascular compromise is important. The degree of swelling and any fracture blisters, whether serous or sanguineous, should be recorded. Palpation of the compartment at the fracture site is an important means of determining the tightness of the compartment. Active motion of the toes, pain on passive stretch, and hypesthesia should be noted. If compartment syndrome is suspected, then pressure measurements are valuable. With careful monitoring, any patient who develops a preoperative or postoperative compartment syndrome requires release of the compartments and stabilization with a nail. Open fractures should be carefully evaluated and the fracture wound classified according to Gustillo and Anderson. Patients with both closed and open fractures should be placed in a long-leg splint during the interval between injury and intramedullary nailing.

Patients with closed fractures should be given a cephalosporin one hour before and 24 hours after the nailing procedure. Patients with open fractures should also be treated with cephalosporin for 48 to 72 hours, and if the fractures are contaminated, they should also concomitantly receive aminoglycosides.

A preoperative anteroposterior (AP) and lateral radiograph of the fractured extremity, including both the knee and the ankle, is critical for defining the fracture and geometry of the tibia and the injury. The lateral radiograph should be carefully inspected, and the size of the intramedullary canal should be measured. An ossimeter is used to measure the tibia so that the length and diameter of the nail can be established. Positive nail-design features include static and dynamic interlocking holes, oblique holes for proximal fractures, clustered distal holes for distal fractures, and cannulation for ease of placement over a guide wire as well as for removal of any broken nail.

Surgery

Anesthesia

General anesthesia is preferred for tibial nailing. If a spinal is used, it should be very short-acting because evaluation of the neurologic status and pain level is very important after surgery. A continuous epidural should be avoided in the treatment of tibial fractures: Although it may provide pain relief for the patient, it makes clinical compartment monitoring difficult.

Prep and Drape

A tourniquet is placed on the thigh but rarely inflated. The entire limb is prepped and draped. If the fracture is open, the traumatic wounds are irrigated and débrided. The traumatic wound is commonly extended to improve exposure and visualization. All nonviable cortical fragments are removed as are foreign bodies or necrotic tissue. The debridement must be orderly, sequential, and complete to render the wound surgically sterile in preparation for the nailing. The fracture ends are carefully inspected and cleaned to ensure that the proximal and distal intramedullary canal is free from debris. If the degree of contamination is high and the wound cannot be reliably rendered clean and sterile, external fixation may be preferable to nailing. The traumatic wound is irrigated, via pulsed lavage, with 9 to 12 L of normal saline.

After the irrigation and debridement, the surgeon’s attention is turned to skeletal stabilization. All instruments used for the washout are removed from the field. The surgeon, assistants, and nurse change into clean gowns and gloves. Then clean, dry, sterile drapes are applied to the patient.

Fracture Reduction

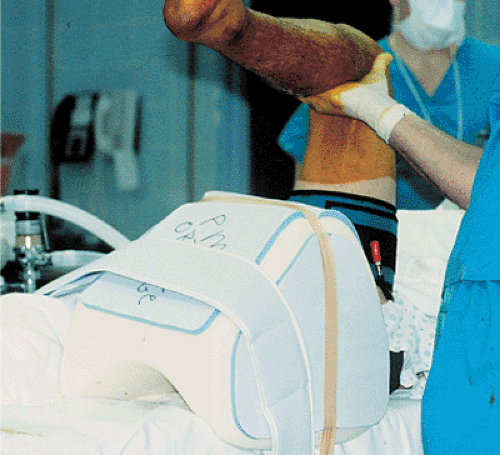

Tibial reduction and nailing can be achieved through the surgeon’s use of a fracture table, a sterile bolster or triangle under the knee, or a distractor. A sterile radiolucent triangle under the knee is the simplest technique and is particularly useful in the treatment of open fractures that require debridement and re-prep before nailing (Figs. 29.8 and 29.9).

The knee is flexed over the triangle, which permits access to the proximal tibia as well as visualization of the starting point.

The knee is flexed over the triangle, which permits access to the proximal tibia as well as visualization of the starting point.

Figure 29.8. AP radiograph of a grade II open fracture with tibial and fibular fracture at same level. |

Figure 29.10. Fracture table. Knee is flexed 90 degrees and peroneal post is against distal thigh rather than popliteal fossa. |

The triangle method presents difficulty for obtaining and maintaining fracture length as well as for controlling angulation and rotation. The assistant also will have difficulty holding the leg perfectly still during distal interlocking. This technique works best with stable fracture patterns.

A fracture table is more complex to set up but is effective in maintaining leg length and rotation during the procedure. It is particularly helpful in nonteaching hospitals where a scrubbed assistant may not be available. With the fracture table, the knee is flexed 90 degrees over a post, which is placed proximal to the popliteal fossa to prevent compression of the vessels or peroneal nerve (Fig. 29.10). Tape is placed around the leg to prevent external rotation of the extremity. A fracture table works best in treating patients with isolated closed injuries of the tibia and is more difficult to use for patients with multiple trauma or open fractures.

A distractor can be used with a pin placed proximally in the posterior tibia and distally just above the ankle joint. In acute fractures, a unilateral frame is usually adequate. After 10 to 14 days, length is more difficult to restore, and a unilateral frame may lead to angulation. Therefore, through-and-through proximal and distal tibial pins are used with a bilateral frame in conjunction with simultaneous medial and lateral distraction. Compared with a bolster or triangle, this method takes longer and is more complex, but it provides good alignment and stability during nailing and interlocking.

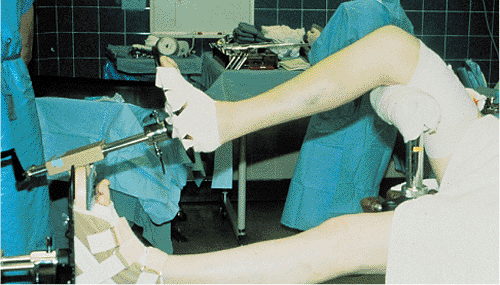

Incision and Starting Point

The joint is palpated and marked on the knee. The incision starts at the joint line and extends proximally (Fig. 29.11). The incision need not go distally down to the tibial tubercle. For fractures of the midshaft or below, the incision and starting point is just medial to the patellar tendon. The joint is palpated, and the awl is inserted where the anterior tibia reaches the joint (Fig. 29.12). The surgeon must stay in the extra-articular area because back out of the nail may impinge on the femoral condyle. He/she must not enter distally at the tibial tubercle, as this leads to a more oblique anterior-to-posterior starting angle, which causes greater risk of nail penetration into the posterior cortex. In proximal third fractures, the incision and starting point is just lateral to the patellar tendon (Figs. 29.13 and 29.14). A sharp, curved, tibial awl is used, and its position is checked in both the AP and lateral planes with an image intensifier before portal placement. On the lateral radiograph, the point of the awl should be on top of the bone (Fig. 29.15). On the AP view, it should be in line with the long axis of the tibia (Fig. 29.16). When treating proximal fractures, the surgeon may find that staying more lateral helps prevent both translation and angulation. The Synthes (Synthes, Paoli, PA) unreamed nail has been a particular problem in proximal tibial

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree