Of the many clinical entities involving the neck region, one of the most intriguing is thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS). TOS is an array of disorders that involves injury to the neurovascular structures in the cervicobrachial region. A classification system based on etiology, symptoms, clinical presentation, and anatomy is supported by most physicians. The first type of TOS is vascular, involving compression of either the subclavian artery or vein. The second type is true neurogenic TOS, which involves injury to the brachial plexus. Finally, the third and most controversial type is referred to as disputed neurogenic TOS. This article aims to provide the reader some understanding of the pathophysiology, workup, and treatment of this fascinating clinical entity.

Of the many clinical entities involving the neck region, one of the most intriguing is thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS). TOS is an array of disorders that involves injury to the neurovascular structures in the cervicobrachial region. A classification system based on etiology, symptoms, clinical presentation, and anatomy is supported by most physicians. The first type of TOS is vascular, involving compression of either the subclavian artery or vein. The second type is true neurogenic TOS, which involves injury to the brachial plexus. Finally, the third and most controversial type is referred to as disputed neurogenic TOS. This article aims to provide the reader some understanding of the pathophysiology, workup, and treatment of this fascinating clinical entity.

Pathoanatomy

There are 3 common locations for compression of the neurovascular bundle in TOS: the interscalene triangle, the costoclavicular space, and the subpectorialis minor space ( Fig. 1 ).

The interscalene triangle is formed by the first rib and the anterior and middle scalene muscles (see Fig. 1 ). Traveling through this space are the trunks of the brachial plexus along with the subclavian artery. There are a number of potential anatomic anomalies in this region that can cause injury to the neurovascular bundle. These structural aberrations include cervical ribs, fibrous bands, rib anomalies, callus formations, tumor, and scalene muscle insertion variation. It has been postulated that congenital soft tissue anomalies in the thoracic outlet region are common and remain symptomatically quiescent until a triggering action prompts these variations into a pathologic state. This action can be in the form of a sudden traumatic event such as a motor vehicle accident, which can cause spasm of the scalene musculature. The inciting cause can also be more gradual, such as from occupational or athletic activities that promote muscular hypertrophy or imbalances.

The costoclavicular space is the second area where compression can occur. It is a triangular region generally located between the clavicle and first rib (see Fig. 1 ). In this region, compressive injury to the neurovascular bundle can be caused by a number of congenital or acquired abnormalities involving the rib, clavicle, subclavian muscle, or costocoracoid ligament. For example, persons with postural issues such as drooping shoulders from deconditioning, a large pendulous breast, or heavy backpack carriage are believed to have a narrower costoclavicular space that may make them susceptible to TOS.

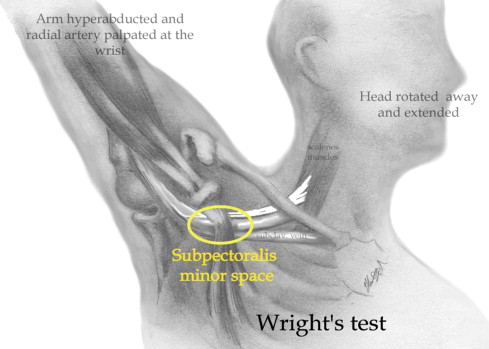

The third location is a region below the coracoid process just under the pectoralis minor tendon. This is referred to as the subpectoralis minor space or the subcoracoid space (see Fig. 1 ). It is believed that compression through this space can occur via mechanisms associated with arm abduction, in which the neurovascular bundle gets stressed underneath a taut pectoralis minor tendon. This positional injury to the neurovascular tissue was first referred to as hyperabduction syndrome by Wright in 1945. It is believed to be observed typically in stocky, short, muscular males who have occupations associated with prolonged overhead activities ( Fig. 2 ).

Epidemiology

Historically, the diagnosis of TOS has been controversial. Consequently, the prevalence of this condition has been poorly documented. The incidences of true neurogenic TOS and vascular TOS have been estimated in some reports to be as rare as 1 case per 1 million people. Disputed neurogenic TOS is more prevalent, and the overall incidence of this form of TOS is reported to range from 3 to 80 per 1000 people. The age of onset is typically between 20 and 40 years and overall TOS is reported to be more common in women than men.

Epidemiology

Historically, the diagnosis of TOS has been controversial. Consequently, the prevalence of this condition has been poorly documented. The incidences of true neurogenic TOS and vascular TOS have been estimated in some reports to be as rare as 1 case per 1 million people. Disputed neurogenic TOS is more prevalent, and the overall incidence of this form of TOS is reported to range from 3 to 80 per 1000 people. The age of onset is typically between 20 and 40 years and overall TOS is reported to be more common in women than men.

Clinical presentations

Arterial TOS

Arterial TOS is reported to account for 1% to 5% of all TOS cases. This form of TOS is the result of compression of the subclavian artery in the region of the interscalene triangle. In a retrospective study of 50 cases of arterial TOS, Durham and colleagues found that the causative factor in most cases was a bony anomaly such as a cervical or anomalous first rib. The patient with arterial TOS may complain of intermittent arm pain, paresthesia, and fatigability with use or overhead positioning. Additionally, there may be findings of weakness, coolness, pallor, and diminished pulse in the affected extremity. In severe arterial TOS, vessel damage could result in poststenotic aneurysm or distal embolic occlusions causing advanced ischemic damage to the extremity. As such, this makes arterial TOS the most threatening form of the syndrome.

Venous TOS

Venous TOS represents 2% to 3% of all forms of TOS. Venous TOS typically results from compressive injury to the subclavian and/or axillary vein in the costoclavicular space. Compromise to the vascular structures can occur via 2 mechanisms: (1) a positional compression of the vein between the clavicle and first rib with overhead activities; or (2) repeated friction between the vein and clavicle, which triggers an intravascular thrombotic mechanism. Moreover, the clinical manifestations vary based on the mechanism of vascular insult. In patients with positional compression, an intermittent uncomfortable heaviness and swelling of the affected arm may be reported with overhead use. Patients with symptoms resulting from thrombosis may have pain along the course of the axillary vein with edema and cyanosis in the upper extremity associated with distended collateral superficial veins in the shoulder and anterior chest. Serious complications of advanced venous thrombosis are pulmonary embolus, severe pain, and edema.

Neurogenic TOS

Accounting for 90% to 97% of TOS cases, the neurogenic type has been subdivided into “true” neurogenic TOS (N-TOS), and more common “disputed” neurogenic TOS. Both forms are secondary to compressive or traction injury typically to the lower trunk of the brachial plexus. True neurogenic TOS has earned the “true” designation owing to anatomic and electrodiagnostic evidence that supports the diagnosis. In contrast, the “disputed” neurogenic TOS, also known as common or nonspecific TOS, is believed by many to be a vague clinical entity lacking any objective clinical findings.

The classical form of true neurogenic TOS is called Gilliatt-Summer Hand. This syndrome was first described in 1970 as thenar, hypothenar, and interossei weakness and/or atrophy, plus ulnar and medial antebrachial cutaneous hypoesthesia in the affected arm. Patients with true neurogenic TOS may report an array of symptoms involving pain, numbness, paresthesia, and weakness in the upper extremity. Aggravating activities may be overhead arm maneuvers and lifting heavy objects.

Approximately 85% of patients diagnosed with TOS are thought to have the disputed type. This form of TOS is reportedly associated with an ill-defined and inconsistent symptomatology in the absence of confirming objective evidence. Therefore, it has been shrouded in controversy, with a number of physicians questioning its very existence. Patients with disputed neurogenic TOS will have similar complaints of paresthesia and weakness as those with neurogenic TOS. However, there usually are more complaints of pain. Additionally, there may be other symptoms more proximal to the thoracic outlet such as vision/hearing disturbances, headaches, and facial pain. This myriad of symptoms is thought to be a result of the variability between upper versus lower compression sites of the brachial plexus. Triggering factors are thought to be repetitive motion disorders, postural issues, or traumatic movements of the neck or shoulder that can cause dysfunction to the scalene musculature.

Diagnosis

The workup for TOS begins with a thorough history, with attention to any trauma to the shoulder or neck region. Any occupational or athletic activities that involve prolonged use of the upper extremities in awkward positions should be appreciated. One must also be mindful of the differential diagnosis of upper extremity pain, weakness, and sensation changes.

The physical examination is crucial to the diagnosis of TOS. During visual inspection of the cervical region, an assessment of muscle asymmetry, deformities, and posture should be noted. A careful comparison between the upper extremities should be made with attention to atrophy, color, edema, moisture, and hair growth.

Other important aspects of the examination include palpation for tenderness, texture changes, masses, or vascular pulsations in the cervicothoracic region. Additionally, finger pressure or percussion should be applied to the supraclavicular fossa to determine if symptoms distally in the arm can be elicited. Finally, a thorough neurologic examination of the cervical spine and upper extremities, including range of motion and strength testing, should be performed.

There are a number of provocative tests that may assist in the diagnosis of TOS. By mechanically stressing specific regions between the neck and shoulder, these physical maneuvers are intended to cause temporary neurologic or vascular derangement. However, the sensitivity and specificity of these tests is relatively low.

In the Adson test, the interscalene space is thought to be stressed. In this test ( Fig. 3 ), the patient is sitting, with the examiner’s fingers placed over the radial artery. The patient’s arm is then externally rotated and extended while palpating the radial pulse. The patient then extends and rotates the neck toward the test arm and takes a deep breath. The production of an absent or diminished radial pulse is suggestive of compression of the subclavian artery by the scalene muscles.

Another provocative maneuver to determine vascular compromise is the Allen test. The patient is seated with the test shoulder placed in 90 degrees of abduction and external rotation, and the elbow in 90 degrees of flexion. The examiner stands with his or her fingers over the radial artery at the wrist. As the patient rotates the neck away from the test arm the examiner palpates the radial pulse. An absent or diminished radial pulse is suggestive of TOS.

To test for impingement at the costoclavicular region, the military brace test ( Fig. 4 ) can be used. With the patient standing at rest, the patient is asked to retract and depress the shoulders. The humerus is then extended 30 degrees with the neck hyperextended. In this position the space between the clavicle and first rib diminishes. If the radial pulse disappears, this suggests impingement of the subclavian artery at the costoclavicular region.