Abstract

Objective

To assess the impact of therapeutic education programmes for Coronary Artery Disease (CAD) and Chronic Heart Failure (CHF), as well as patients’ expectations and education needs, tips to improve adherence to lifestyle modifications, and education materials.

Method

We conducted a systematic review of the literature from 1966 to 2010 on Medline and the Cochrane Library databases using following key words: “counselling”, “self-care”, “self-management”, “patient education” and “chronic heart failure”, “CAD”, “coronary heart disease”, “myocardial infarction”, “acute coronary syndrome”. Clinical trials and randomized clinical trials, as well as literature reviews and practical guidelines, published in English and French were analysed.

Results

Therapeutic patient education (TPE) is part of the non-pharmacological management of cardiovascular diseases, allowing patients to move from an acute event to the effective self-management of a chronic disease. Large studies clearly showed the efficacy of TPE programmes in changing cardiac patients’ lifestyle. Favourable effects have been proved concerning morbidity and cost-effectiveness even though there is less evidence for mortality reduction. Numerous types of intervention have been studied, but there are no recommendations about standardized rules and methods to deliver information and education, or to evaluate the results of TPE. The main limit of TPE is the lack of results for adherence to long-term lifestyle modifications.

Conclusion

The efficacy of TE in cardiovascular diseases could be improved by optimal collaboration between acute cardiac units and cardiac rehabilitation units. The use of standardized rules and methods to deliver information and education and to assess their effects could reinforce this collaboration. Networks for medical and paramedical TPE follow-up in tertiary prevention could be organized to improve long-term results.

Résumé

Objectif

Évaluer l’impact des programmes d’éducation thérapeutique dans les maladies coronariennes (CAD) et l’insuffisance cardiaque chronique (ICC), ainsi que les attentes des patients et les besoins éducatifs, les conseils pour améliorer l’adhésion aux modifications d’hygiène de vie, et la qualité des supports éducatifs.

Méthode

Revue systématique de la littérature sur les bases de données Medline et Cochrane Library, de 1966 à 2010, en utilisant les mots clés: « counseling », « self-care », « self-management », « patient education » and « chronic heart failure », « coronary artery disease », « coronary heart disease », « myocardial infarction », « acute coronary syndrome ». Les essais cliniques randomisés ou non, ainsi que les revues de littérature et les recommandations pratiques, publiées en anglais et en français ont été analysés.

Résultats

L’éducation thérapeutique du patient (ETP) fait partie intégrante de la prise en charge non-pharmacologique des maladies cardiovasculaires, permettant aux patients de passer d’un événement aigu à l’autogestion efficace d’une maladie chronique. De grandes études ont clairement montré l’efficacité des programmes éducatifs, en changeant les habitudes de vie des patients cardiaques. Des effets favorables ont été démontrés sur la morbidité et les coûts médicaux, même si il y a moins de preuves sur la réduction de la mortalité. De nombreux types d’interventions ont été étudiés, mais il n’existe aucune recommandation sur les règles et méthodes standardisées pour fournir l’information et l’éducation, ni pour l’évaluation des résultats de l’ETP. La principale limite de l’ETP est le manque de résultats d’observance à long terme des modifications durables du style de vie.

Conclusion

L’efficacité de l’ETP dans les pathologies cardiovasculaires pourrait être améliorée grâce à une collaboration optimale entre les services de cardiologie aiguë et les centres de réadaptation cardiaque. L’utilisation de recommandations et de méthodes standardisées pour livrer les informations ainsi que l’éducation et évaluer leurs effets, pourrait faciliter cette collaboration. L’organisation de réseaux médicaux et paramédicaux pour l’ETP de suivi dans la prévention tertiaire pourrait être proposée afin d’améliorer les résultats au long terme.

1

English version

1.1

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease is the main cause of mortality and disability in developed countries , generating permanent and high medical costs. Improvement in the initial management of these diseases in recent years has led to a decrease in mortality, especially in the acute phase . This has resulted in an epidemiological change in our health-care environment, for which the major challenge is the long-term management of chronic diseases in a population that is getting older and older. However, persons who suffered from cardiac disease have a persistent higher risk of recurrence compared with the general population . According to the results of the recent PURE study , optimal medical treatment after a cardiovascular event is still under-prescribed, more so in rural than in urban areas, and the poorer the country the lower the prescription rate. Evidence from the literature suggests that non-pharmacological recommendations or guidelines are not being applied either. Indeed, recent studies showed that patients adhere less to lifestyle modifications than to their drug regimens one month after acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and that only a quarter of patients adhere to their drug regimens after myocardial infarction .

The results of the “European Action on Tertiary and Primary Prevention by Intervention to Reduce Events” (EUROASPIRE) one, two and three studies conducted in eight countries at 4-years intervals, showed that in post-MI patients, the control of cardiovascular risk factors (CVRF) is still far below an acceptable level . In France, the situation is similar: the PREVENIR study conducted in 1394 patients in the post-MI period or presenting unstable angina showed that, at 6 months, 50% were still current smokers, 66% had blood levels of LDL cholesterol that were higher than the French Agency for the Safety of Health-Care Products (AFSSAPS) recommendations and that 27.4% had non-controlled arterial hypertension .

Therapeutic patient education (TPE) to improve secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease has been around for many years. It is regularly employed in cardiology and rehabilitation units though with some differences in the way it is managed. The education of patients on the control of CVRF together with reconditioning to effort is a fundamental aspect of cardiovascular rehabilitation. In the comprehensive multidisciplinary management of cardiovascular rehabilitation, TPE is a priority as it significantly improves compliance and the results of secondary prevention . The results of the PREVENIR study clearly showed better results in rehabilitated patients who benefited from TPE . However, only a small proportion of patients who suffered from cardiovascular disease are enrolled in rehabilitation programmes , which are strongly recommended and have proven their efficacy .

The main objective of TPE is to improve management of the disease by the patient and thus reduce morbidity or the onset of certain complications or incidents. One of the secondary objectives is economic: a reduction in the need for treatment, which may lead to reduced direct or indirect costs as already shown in asthma or diabetes . However, though there are many arguments in the literature that share this point of view, whether TPE has a significant impact on the economic burden of treating CAD patients in a healthcare system remains to be proven .

Though TPE can be implemented in different ways, the general objectives always focus on the goals of secondary prevention after cardiovascular diseases . Each of the steps of TPE is generally respected with first an assessment of patients expectations and education needs, then the education intervention and finally evaluation and follow-up. A lot of tools are used but few of these have been validated. It is therefore difficult to evaluate the long-term results with regard to the different modalities used.

In 2011, The French Society of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (SOFMER) published several reviews about TPE in chronic illness . A work group dedicated to cardiovascular TPE was developed in order first to review the literature and then to write specific recommendations on the subject.

1.2

Objective

The objective of this article was to clarify the impact and the modalities of TPE programmes in the management of cardiovascular diseases. This clarification was undertaken within the framework of the national project about TPE initiated by the SOFMER. Particular attention was paid to validated tools that could contribute to the assessment of patients’ expectations, knowledge and education needs. Factors that limit the implementation and efficacy of these programmes were also highlighted. We also considered the optimal way to implement TPE (when and how), and described the main standardized materials used for TPE in cardiovascular disease. Finally, we described the main results of large studies investigating the impact of therapeutic education programmes.

1.3

Material and methods

A systematic review of the literature was performed through a search of the Medline, PubMed and Cochrane Library databases for work published between 1966 and 2010. Given the many symptoms that can be the subject of TPE, they were arbitrarily grouped based on the advice of the group of experts (group SOFMER), and the bibliographic search was defined using the following complementary keywords: “counselling”, “self-care”, “self-management”, “patient education” and “chronic heart failure”; “coronary artery disease (CAD)”; “coronary heart disease”; “myocardial infarction”; “ACS”. Articles were selected on the basis of their abstracts. We selected articles on randomized controlled studies, clinical trials, reviews and guidelines in French or in English that included at least one educational intervention for cardiovascular disease in adult subjects, and the analysis of its result as one of the primary outcomes. The reference lists of selected articles were also searched for articles meeting our inclusion criteria but not present in the initial search results. We focused on papers treating the following fields:

- •

validated tools used for the assessment of patients’ expectations, knowledge and education needs;

- •

obstacles to the implementation of TPE programmes in everyday practice, and the identification factors that had a positive or negative effect on the TPE intervention;

- •

implementation of the TPE programme (when and how?);

- •

description of materials used to implement TPE in cardiovascular disease;

- •

and the impact of the therapeutic education programmes. In order to be as exhaustive as possible, primary prevention approaches were considered – even though they are not strictly part of TPE (i.e. secondary prevention)

1.4

Results

We retrieved 101 articles, 77 of which directly dealt with TPE tools or assessment in cardiovascular disease. Other references concerned epidemiological data, and tools or methods more usually used in TPE, but not specific to cardiovascular disease.

1.4.1

Tools used for the individual assessment of patients’ expectations, knowledge and education needs, and evaluation of the impact of therapeutic patient education programmes

Many tools can be used to assess patients’ expectations, knowledge and education needs about various CVRF. The most used or best validated, described below, concern dietary evaluations, smoking cessation or dependence, physical activity (PA), psychological status, self-care behaviour, and health-related quality of life.

1.4.1.1

Dietary evaluation

Different dietary objectives of TPE according to disease were searched for. Though the principles of the Mediterranean diet were always followed , there were also frequent recommendations for calorie reduction, control of salt intake, or specific recommendations for diabetics. Specific tools have been developed to evaluate adherence to the Mediterranean diet, including the 10-unit Mediterranean diet score. A gain of two points in this score is associated with a 27% reduction in all-cause of mortality . However, as it is based on an extensive questionnaire including questions about the regular consumption of approximately 150 different foods and beverages common in Greece, it is hard to use in clinical practice. Another shorter questionnaire has been validated in French for use in patients after ACS . Using this questionnaire, a recent study showed an improvement in eating habits after a specific programme of nutritional counselling during cardiac rehabilitation for CAD . Despite these good results, these questionnaires are rarely employed in secondary prevention , probably because their use and/or interpretation is still time-consuming.

1.4.1.2

Smoking cessation

The evaluation of smoking is well documented in the literature. The Fagerstrom score is the most widely used to evaluate nicotinic dependence, but it has not been extensively validated , even with the Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence, which is a revised form of the initial Fagestrom score. Moreover, the psychometric properties of the French version of this questionnaire are not known. Q-MAT is a specific questionnaire to estimate the strength of the motivation to stop smoking. It has been validated in French and includes four questions with total score of 20. A total score up to 12 indicates good motivation to stop smoking. Specific tools like the CO-meter are recommended to control smoking cessation during the follow-up of patients .

1.4.1.3

Physical activity

A lot of questionnaires are available but these take a long time to administer or interpret, and few have been especially validated in patients with heart disease . Moreover, they are often validated against maximal exercise capacity rather than real activity measurements such as actimetry. The Dijon PA Score is one of these tools and could be used in French . Other tools like the pedometer or accelerometer can be used in this kind of patient with accurate results for the assessment of PA. One of the main advantages of accelerometer devices is that they allow the “real time” assessment of PA. Thus, accelerometers could also be used to provide instant feed-back to help patients to determine if they have reached the recommended PA goal. They could also give the physician an objective measurement of the patient’s compliance with regular PA. However, these apparatus have been little studied in cardiovascular disease . Apart from PA habits, there is a growing body of evidence to support the need for an assessment of self-perceived barriers to PA in cardiac patients . A questionnaire exploring these barriers has been developed and validated in Type 1 diabetes and also tested in patients with Type 2 diabetes , but not in cardiac patients.

1.4.1.4

Psychological evaluation

Non-specific scales are frequently used in psychological evaluation when TPE is started. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale is one of the most widely used in cardiovascular disease. Its validity has been well established in English . Beside the general anxiety evaluation questionnaires, The Cardiac anxiety questionnaire is specific for the evaluation of heart-focused anxiety. It has been partly validated in English in patients with heart disease . Depressive syndrome is a strong cardiovascular risk factor and could be detected easily in the general population. A total score above 20/63 on the Beck depression inventory questionnaire (version II) shows a high probability of depression .

1.4.1.5

Self-care behaviour

Self-care behaviour is the capacity of a subject to manage his disease. It is one of the predictors of good adherence to treatment and lifestyle modification in cardiovascular disease, and so far has been shown to be probably related to a reduction in rehospitalisation . The 12- then 9-item European Heart Failure Self-care Behaviour scale has been validated in English, Japanese , German, Spanish and Italian for the evaluation of self-care behaviour in CHF patients ( Appendix A ). It appraises patients’ ability to manage weight, dyspnoea, fatigue, medications and exercise. It only takes 5–10 min to complete and is easy to understand, usually with no missing data. This scale is probably useful to detect the need for TPE and to test the efficacy of TPE programmes. However, there are no gold standard criteria to assess its sensitivity to change, and very few studies have used it to assess TPE programmes .

1.4.1.6

Health-related quality of life

The quality of life refers to the patient’s ability to enjoy normal activities of everyday life. This concept has been studied in cardiovascular disease, but it remains difficult to appreciate because it is complex and multidimensional, and there are no perfect tools to assess it . There are generic scales like SF-36 (validated in French ) or EuroQol (validated in French ) and specific scales like the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire (validated in French ). These scale are currently used to evaluate TPE programmes in cardiovascular diseases . The MacNew Heart Disease quality of life questionnaire has been validated in English in a specific population of patients with heart disease. It is an autoquestionnaire with 27 items grouped in three main domains (physical limits, social and psychological wellbeing).

1.4.2

Factors influencing therapeutic patient education results

1.4.2.1

Observance factors

TPE in cardiac disease must concern the specific evaluation of factors that indicate a risk of non-adherence to long-term lifestyle modification (compliance with treatment, diet and PA). Indeed, special educational support should be given to these patients particularly in the form of a closer follow-up. These factors could be studied during the assessment of the patient’s expectations and education needs. The main factors are altered cognitive performance, low level of self-efficacy, a type D personality profile, fear about treatment or PA, a low level of physical performance, depression, co-morbidities, a low socioeconomic status .

1.4.2.2

Personality aspects

So called type A, characterized by elements of competitiveness and impatience, has been associated with an increased likelihood of ACS whereas type D, with predominant elements of social inhibition and repression of emotions, is more often quoted in patients with peripheral artery diseases . These differences in the psychological profile of patients have not, however, resulted in large-cohort studies. Nonetheless, they do have implications for the management of patients, particularly with regard to their capacity to adhere to a TPE programme: greater fighting spirit for type A and hence better prognosis in the control of risk factors, usual denial for type D, which compromises adherence. Type D patients are more likely to develop avoidance strategies towards situations of discomfort and pain, thus inducing low levels of activity, which will accelerate the deconditioning spiral. It seems possible to intervene on certain features of the patients’ personality, essentially on the affective aspect.

1.4.2.3

Motivational speech

After an acute cardiac event, lifestyle modification is sometimes not a priority for patients. TPE is difficult in ACS patients and must differ from the classical approach used in most other patients. In this case, heath professionals should develop motivational interactions with their patient in order to shift the patient from a precontemplative situation to active behaviour in favour of lifestyle modifications .

1.4.2.4

Evaluation of satisfaction

The satisfaction and participation of the patient are essential in any educational process that aims to modify lifestyle habits, in order to obtain active participation in disease management. A very simple (but not specific) means to assess patient satisfaction is a visual or numeric scale from 0 (bad) to 10 (very good) with different evaluation subjects (reception, content of learning, personal results…). There is a special scale, the Goal Assessment Scale (GAS), to assess this type of intervention . The principle is first to define personal objectives for each patient, then to attribute a weight to each (importance × difficulty) and finally to ask patients about their satisfaction with the five graduation for each objective (−2 to +2). However, this scale has not been evaluated in this kind of approach.

1.4.2.5

Evaluation of results

Most of the evaluations used assess the specific cardiovascular risk. These include lipid profile, glycaemia balance, arterial pressure, weight or PA. Another kind of evaluation is knowledge status of patients before and after TPE, most of the time assessed using questionnaires . To date, there are no specific recommendations about the type of evaluation.

1.4.3

Modalities of cardiovascular therapeutic education

1.4.3.1

When?

No studies have compared the timing of the TPE intervention in heart disease. It is thus hard to draw any conclusions about the optimal time to implement TPE. Indeed, given the different profiles of patients, there is probably no unique answer. In the literature, the time to the beginning of TPE is vague but TPE is generally started soon after discharge following hospitalisation for the acute event with good results . Little is known about early TPE started while the patient is still in hospital. Currently, a specific tool to deliver this kind of TPE very soon after the acute cardiac event is being developed in France. In a pragmatic approach, it is clear that the content of the TPE programme has to be adapted to the patient according to the educative diagnosis from which the motivation to change is graded according to the Prochaska level . Cardiac rehabilitation seems to be a particularly opportune time to propose TPE within an individualized global programme for secondary prevention, in the absence of marked symptoms of depression. Indeed, in the aftermath of a major health event (ACS, coronary revascularization…), adherence to and psychological compliance with the interventions that aim to reduce the risk of recurrence are usually good. The objectives can be set with the patient with specific goals such as blood pressure, glucose and lipid profile, smoking cessation, PA and weight control.

1.4.3.2

How?

Several forms of TPE can be found for individual or group interventions. Telephone interventions alone seem less effective than global centre-based approaches . The number of hours of TPE varies, generally between 5 and 10 h and the content is always the same: nutrition, PA, smoking cessation, medical drugs, disease comprehension, sexuality, and social adaptation to the disease . TPE is generally more intensive in cardiac units (condensed programme over two consecutive days separately for example ) and spread over a longer period in rehabilitation centres because patients stay for a longer time (3 to 6 weeks).

1.4.3.3

Who?

According to the literature, an interdisciplinary approach is the most acceptable. Individual interventions (nurses or medical doctors) are less efficacious . Besides medical doctors or paramedics, pharmacists can play a crucial key role in TPE .

1.4.3.4

Follow-up

There are no recommendations about follow-up after TPE in patients with cardiovascular disease. It is clear that there is need for complementary evaluations in the months following TPE. In their return to “real life” patients often return to their previous habits, and thus the effects of the TPE soon wear off. Maintaining long-term changes in lifestyle in cardiovascular disease is a major health challenge. It therefore seems interesting to develop “booster” sessions or remote support in high risk or low-compliance patients, in coordination with the various members of the medical (doctor, cardiologist, cardiovascular surgeon, diabetologist, angiologist…) and paramedical team (nurses, physiotherapists, dietician, kinesiologist…), all of whom have to provide sequential or continuous support to the patient. Bocchi et al. found that repeated sessions of education every six months were followed by only 54% of patients at about 2 years, with, however, good results in terms of rehospitalisation or quality of life. In French cardiac rehabilitation programmes, re-evaluations are usually done by telephone alone, but long-term results about adherence have not been evaluated. Moreover, there is often no coordination between rehabilitation centres and cardiac units for TPE. Finally, e-health could help professionals to follow patients after TE especially in chronic heart failure .

1.4.4

Materials used for therapeutic patient education in cardiovascular disease

With the collaboration between learned societies and the pharmaceutical industry, education materials have been developed with packages or “kits” including pedagogical tools for TPE on the main CVRF. The advantage of these tools is their easy-to-use format. Nonetheless, they must only be the support to promote the key message of TPE according to the initial educational diagnosis.

In patients with a high-risk cardiovascular profile, a specific education tool, PEGASE Project has been designed in order to help doctors and paramedics to dispense TE in these patients. After an educational diagnosis, the specific themes tackled with patients concern diet, PA, treatments and cardiovascular diseases. It is organised in six sessions (four in groups, two one-to-one). This project was evaluated in 256 patients, and led to improvements in lipid profile, and quality of life at six months .

Similarly, the ICARE project was developed to create specific tools for TPE for patients with chronic heart failure. This programme includes five modules: educational diagnosis, knowledge of the disease, diet, PA and daily living, and drugs. A knowledge questionnaire was given before and after the TPE programme at 136 centres to evaluate practices among users of ICARE. The results showed that the programme was usually covered during four out-patient sessions for a total of 6 hours. Almost all of the centres included (89%) usually completed the entire programme .

1.4.5

Efficacity of therapeutic education in cardiovascular disease

1.4.5.1

Coronary Artery Disease

In 2005, Clark et al. published a meta-analysis to evaluate the efficacy of TPE after ACS. Sixty-four high-quality studies were analysed (19 441 patients), including programmes based on TPE plus exercise (24 studies) and studies using either one or the other (23 studies for education, 17 studies for exercise). Forty studies dealt with overall mortality, and 27 with ACS recurrent risk. Total mortality ACS recurrence were significantly decreased (RR = 0.85 [95% CI: 0.77–0.94] for mortality and 0.83 [95% CI: 0.74–0.94] for ACS recurrence, respectively) with no difference between the type of intervention:

- •

programmes including education or counselling on risk factors with a structured exercise component (RR = 0.88 [95% CI, 0.74 to 1.04] for mortality and 0.62 [95% CI, 0.44 to 0.87] for ACS recurrence);

- •

programmes including education or counselling on risk factors with no exercise component (RR = 0.87 [95% CI, 0.76 to 0.99] for mortality and 0.86 [95% CI, 0.72 to 1.03] for ACS recurrence);

- •

and programmes exclusively based on exercise (RR = 0.72 [95% CI, 0.54 to 0.95] for mortality and 0.76 [95% CI, 0.57 to 1.01]for ACS recurrence).

This work shows the favourable synergic effects of TPE and exercise training. These results are different from those of the previous meta-analysis conducted by McAlister in 2001 where no effect on mortality was found . Finally, Clark et al. pointed out that two trials reported that their intervention was cost-saving and only one trial performed formal cost-effectiveness analyses, and demonstrated an incremental cost per quality-adjusted life-year of £1097 .

More recently, the GOSPEL study confirmed the efficacy of TPE in a multicentre randomized control trial involving 3241 patients. A significant decrease was found in the combination of cardiovascular mortality, non-fatal myocardial infarction and stroke at three years follow-up (absolute risk decreased by 33% [95% CI, 0.47–0.95] ( P = 0.02); RR = 0.67 [95% CI, 0.47–0.95]). A significant improvement was also found in lifestyle habits (greater proportion of patients in the intervention group adhering to PA guidelines, Mediterranean diet, smoking cessation, and stress management). These results were consistent with an improvement in lifestyle modifications in the TPE group compared with control. In line with these results, the EUROACTION Study , a RCT including 3088 patients after an acute ischemic cardiac event, showed that a home-based TPE programme could increase the consumption of fruit, vegetables and oily fish, and reduce that of fat and unsaturated fat after one year of follow-up compared with the control group. There was, however, no effect on smoking.

The main effects of TPE in secondary prevention reported in large randomized studies are therefore consistent, and some authors suggested that a programme of TPE could replace rehabilitation programmes when they are difficult to implement (areas without an appropriate centre, difficulties to schedule, in workers for instance). Indeed, only about 20–30% of patients can benefit from such programmes after ACS in France . The CHOICE study compared a TPE programme with a rehabilitation programme and a control group after ACS. At 12 months, the control of CVRF in patients on the TPE programme were no different from those of the rehabilitation group and significantly better than those of the control group. However, in this study, no data were published about the aerobic capacity of the patients, which is considered a strong prognostic factor , and no results were reported about mortality. An RCT of nursing interventions found that telephone intervention by nurses had a positive effect on the management of cardiac risk factors, quality of life and attendance at a cardiac rehabilitation programme. However, no effects were found in the reduction of cardiac mortality after ACS.

The three main studies in the field are more exhaustively described in Table 1 .

| Reference | Population | Design | Intervention | Outcomes | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moher et al. 2001 | n = 1906 Mean delay after ACS = 8.3 years | RCT | Audit of notes with summary feedback to primary health care team (audit group); assistance with setting-up a disease register and systematic recall of patients to general practitioner (GP recall group); assistance with setting up a disease register and systematic recall of patients to a nurse led clinic (nurse recall group) | At 18 months’ follow-up Target reached for 3 risk factors (blood pressure, cholesterol, and smoking status); prescribing of hypotensive agents, lipid lowering drugs, and antiplatelet drugs | Improvement in drug therapy prescription (anti platelet) No difference concerning blood pressure, lipid control or tobacco use |

| Murchie et al. 2003 | n = 1343 Mean delay after ACS = not available | RCT | Nurse led secondary prevention clinics promoting medical and lifestyle components of secondary prevention and offering regular follow up for one year | Components of secondary prevention (aspirin, blood pressure management, lipid management, healthy diet, exercise, non-smoking), total mortality, and coronary events (non-fatal myocardial infarctions and coronary deaths) | Improvement of all risk factors except for tobacco at one year and exercise at four years Significant decrease in total mortality |

| Giannuzzi et al. 2008 | n = 3241 Mean delay after SCA = 60.4 days | RCT | Educational and behavioural intervention by a nurse specialized in cardiology and rehabilitation, a physiotherapist, and a cardiologist; one session per month for 6 months then every 6 months for 3 years | Primary endpoint: Combination of cardiovascular (CV) mortality, non-fatal MI, non-fatal stroke, and hospitalization for angina pectoris, heart failure, or urgent revascularization procedure was the primary end point Secondary endpoints: CV events, major cardiac and cerebrovascular events, lifestyle habits, and drug prescriptions | No difference concerning the primary end point Significant decrease of CV mortality plus non-fatal MI and stroke absolute risk decrease = 33% [95% CI, 0.47–0.95] ( P = 0.02); RR = 0,67 [95% CI, 0.47–0.95] Improvement of lifestyle habits (physical activity, diet, stress management, smoking rate) |

1.4.5.2

Chronic heart failure

For Chronic Heart Failure, a meta-analysis conducted by McAllister proved the efficacy of TPE in reducing the likelihood of re-hospitalisation, particularly when a multidisciplinary approach (Cardiologist, specialist nurse, pharmacist, dietician, or social worker) was used in a cardiac unit specialised in heart failure management. These results have been confirmed by further systematic reviews and metaanalyses . However, in these studies the effect on mortality remains unclear. The study by Jaarsma et al. was the biggest randomized control trial with 1023 CHF patients enrolled in a TPE conducted by nurses specialized in the management of heart disease. This study showed no effect on mortality. The three main studies concerning TPE in HF are more exhaustively described in Table 2 .

| Reference | Population | Design | Intervention | Outcomes | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rich et al. 1996 | n = 282 | RCT | Intervention group = Nurse-directed, multidisciplinaryintervention comprising comprehensive education of the patient and family, a prescribed diet, social-service consultation and planning for an early discharge, a review of medications, and intensive follow-up Control group = usual care | Primary endpoint = survival without Hospital readmission Secondary endpoints = hospital readmission, quality of life, and care costs (At 90 days after intervention) | Primary endpoint: not significant Significant decrease in hospital readmission (−13.2% [95% CI, 2.1–24.3, P = 0.03] and medical costs Improved quality of life |

| De la Porte et al. 2007 | n = 240 | RCT | Intervention group = 9 scheduled patient contacts – at day 3 by telephone, and at weeks 1, 3, 5, 7 and at months 3, 6, 9 and 12 by a visit – associated with a combined, intensive physician-and-nurse-directed HF outpatient clinic, starting within a week after hospital discharge from the hospital or referral from the outpatient clinic. Verbal and written comprehensive education, optimisation of treatment, easy access to the clinic, recommendations for exercise and rest, and advice for symptom monitoring and self-care were provided Control group = usual care | Primary endpoint = occurrence of hospitalisation for worsening HF and/or all-cause mortality Secondary endpoint = NYHA, Quality of life, left ventricular ejection fraction and cost effectiveness (At 12 months after intervention) | Primary endpoint: absolute difference −21% [95% CI, 7–36]; RR 0.49 [95% CI, 0.30–0.81], P = 0.001 |

| Jaarsma et al. 2008 | n = 1023 | RCT | Patients were assigned to 1 of 3 groups: a control group (follow-up by a cardiologist) and 2 intervention groups with additional basic or intensive support by a nurse specializing in management of patients with HF. Patients were studied for 18 months | Primary endpoints Combination of All causes of death and/or rehospitalization because of HF Number of days lost because of death or hospitalization Secondary endpoints All causes of death All causes of hospitalisation | No significant difference between groups concerning the 2 primary and secondary endpoints |

In addition, in the study by Rich et al. , TPE was found to be cost-effective, with a lower readmission rate (RR = 0.67 [95% CI: 0.45–0.99]; P = 0.05) and a greater improvement in quality-of-life scores at 90 days from baseline for patients in the intervention group, with costs that were 460 dollars lower than in the control group. The same authors , as well as Gwadry-Sridhar et al. found a positive effect on drug compliance and quality of life.

1.5

Conclusions-perspectives

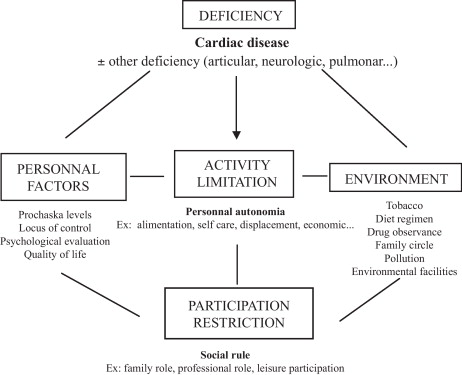

TPE is clearly a fundamental non-pharmacological therapy in the management of heart disease even though more proof is needed in specific cardiovascular diseases like PAD or post-thoracic surgery (CABG, valve replacement, heart transplant). TPE programmes are well established in cardiac units or rehabilitation centres. Relevant limits concern the degree of cooperation between these structures, which should be complementary in managing a patient’s health. In this perspective, early TPE could be interesting to connect the two approaches. More studies are needed to better define TPE programmes for heart disease (optimal time to implement, alone or associated with other interventions), and assess their cost-effectiveness. Concerning the content of the TPE, there is a need for more validated tools to assess patients’ expectations and education needs, and to deliver TPE. In this perspective, a schematic approach could be inspired by the global vision of chronic diseases recommended by the WHO as illustrated in Fig. 1 . Specific behaviour techniques (Cognitive Behavioural Therapy) could also be used to alter lifestyle habits.

The optimal frequency and modalities of the follow-up after the initial TPE programme have to be defined, and perspectives must be developed with interventions using new communication technologies (Smartphone, Internet…). This could allow larger long-term studies on the effects of TPE on lifestyle modifications, in addition to the effects on drug observance. It remains challenging to design comparative studies of TPE programmes, as double-blinded studies cannot be performed, given that the staff performing the intervention can obviously not be blinded to the intervention. This limitation is often encountered in non-pharmalogical interventions. However, some options, such as alternate-month design procedure can help to limit contamination between the groups, and special attention must be given to blind evaluators of the intervention. There cannot be a placebo and perhaps the development of the Zelen method could be suitable . Finally, we have to establish global recommendations that bring together all of the professionals involved in TPE in cardiovascular disease.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest concerning this article.

Appendix A

12-item European Heart Failure Self-Care Behaviour scale

From: Jaarsma T, Stromberg A, Martensson J, Dracup K. Development and testing of the European Heart Failure Self-Care Behaviour Scale. Eur J Heart Fail 2003;5(3):363–70.

| I completely agree | I don’t agree at all | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | I weight myself every day | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2 | If I get short of breath, I take it easy | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 3 | If my shortness of breath increases, I contact my doctor or nurse | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 4 | If my feet/legs become more swollen than usual, I contact my doctor or nurse | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 5 | If I gain 2 kg in 1 week, I contact my doctor or nurse | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 6 | I limit the amount of fluids I drink (not more than 1.5–2 L/day) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 7 | I take a rest during the day | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 8 | If I experience increased fatigue, I contact my doctor or nurse | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 9 | I eat a low-salt diet | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 10 | I take my medication as prescribed | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 11 | I get a flu shot every year | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 12 | I exercise regularly | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree