The Vortex of Disability Determination

Industrialization carried with it many a human cost. For one, what was to become of the incapacitated workers who could not support themselves and their families? As we discussed in Chapter 11, the debate about the worker’s entitlement culminated fin de siècle when Prussia legislated an insurance scheme with three strata of indemnification: Workmen’s Accident Insurance for the worker whose disability is consequent to an injury that arose out of and in the course of employment and occurred by accident, Public Pension Insurance for the worker whose disability arose from causes not related to work, and Public Aid for the disabled individual who was never a wage earner. With some modification, this scheme was adopted across the industrialized world.1 It has rested easily nowhere and has served no group of workers more unevenly than those with regional musculoskeletal disorders.

Workers’ Compensation Insurance was meant to target violent workplace accidents resulting in loss of life or limb or the like. Other catastrophes that are patently work related but not overtly violent are outside its purview; the likes of mercury and lead poisoning or anthrax compensability required new legislation creating “schedules” of occupational diseases. From the outset there were categories of illness in which causation, damage, and incapacity were all contentious. “Writer’s cramp,” “scrivener’s palsy,” and “telegraphist’s wrist” gained sufficient political momentum as a rallying cry of the union movement to be added to the British schedule of compensable diseases in 1908 despite heated debate about etiopathogenesis, which coalesced by 1920 under the rubric “occupational neurosis.”2 “Railway spine” played out in parallel but more in civil law because most of the afflicted were passengers whose “spinal concussion” often followed no more than the joggling and buffeting of rail travel. The leading proponent of the construct, the London surgeon John Eric Erichsen,3 argued late in his career that “traumatic neurasthenia”4 was a more appropriate label. “Railway spine” was a forerunner of the labeling discussed in Chapter 3.

The debate about the work relatedness of regional musculoskeletal disorders lay fallow until closer to the mid-20th century. In 1932 in Boston, Mixter and Barr ascribed backache and radiculopathy to extrusion of the nucleus pulposus and described their surgical remedy.5 They also labeled the disorder the “ruptured” disc. This is an emotive adjective; if the outcome is so dramatic, a “rupture,” the cause need not be so violent. In this fashion, backache that occurred in the course of employment with no unusual precipitant qualified as a compensable “injury,” particularly if the putative cause was the awful “ruptured disc” and certainly if that

diagnosis was certified by the presence of a surgical scar. More recently, labels that implicate compensability, such as “cumulative trauma disorders” (CTDs) or “repetitive strain injuries,” have been applied to regional arm pain. Here the paralogism likens to metal fatigue. The incidence of compensable regional back “injuries” soared from the mid-20th century until approximately a decade ago when it stabilized as the incidence of compensable regional arm “injuries” soared. Today the majority of the indemnity costs (i.e., the awards for disability as opposed to medical care) for most Workers’ Compensation schemes relates to regional back and arm pain that affect a small minority of all claimants.6 That means there are escalating numbers of working-age adults who are permanently disabled to some extent by pain when they move their trunk or arm.7,8 The national average of total benefits (cash plus medical expenditures) per 100,000 workers approached $50 million by the end of the last decade9 with considerable regional variability such that the cash benefits for permanent partial disability for the California workforce was twice the national average.10 This trend has defied all the advances in industrial hygiene and safety that have rendered the workplace safer in terms of death and dismemberment. It is this paradox that is generating the cry for reform. And it is on the basis of this paradox that, again fin de siècle, the debate is rejoined. The difference is that on this go-round there are substantive insights that might inform the debate, insights gained from systematic studies of the dilemma faced by workers with compensable regional musculoskeletal illness.

diagnosis was certified by the presence of a surgical scar. More recently, labels that implicate compensability, such as “cumulative trauma disorders” (CTDs) or “repetitive strain injuries,” have been applied to regional arm pain. Here the paralogism likens to metal fatigue. The incidence of compensable regional back “injuries” soared from the mid-20th century until approximately a decade ago when it stabilized as the incidence of compensable regional arm “injuries” soared. Today the majority of the indemnity costs (i.e., the awards for disability as opposed to medical care) for most Workers’ Compensation schemes relates to regional back and arm pain that affect a small minority of all claimants.6 That means there are escalating numbers of working-age adults who are permanently disabled to some extent by pain when they move their trunk or arm.7,8 The national average of total benefits (cash plus medical expenditures) per 100,000 workers approached $50 million by the end of the last decade9 with considerable regional variability such that the cash benefits for permanent partial disability for the California workforce was twice the national average.10 This trend has defied all the advances in industrial hygiene and safety that have rendered the workplace safer in terms of death and dismemberment. It is this paradox that is generating the cry for reform. And it is on the basis of this paradox that, again fin de siècle, the debate is rejoined. The difference is that on this go-round there are substantive insights that might inform the debate, insights gained from systematic studies of the dilemma faced by workers with compensable regional musculoskeletal illness.

THE ADMINISTRATION OF THE WORKERS’ COMPENSATION INSURANCE PROGRAM IN THE UNITED STATES

Social legislation did not cross the Atlantic with lightning speed. In fact, the American version of Invalid Pension, Social Security Disability Insurance, took more than 50 years in the crossing (see Chapter 10). However, the injured worker in America, in parallel with events in Europe, was gaining power in the courts and a union voice early in the century. The only effective political pressure at that time was for Workers’ Compensation Insurance statutes. Driving the movement were the same interests that operated in Europe. However, legislating insurance somehow seemed unconstitutional in the United States, a form of taxation beyond constitutional limits. For that reason, the American program took some relatively unique twists. The program was not to be a national program. Rather, each state, several territories, and federal entities developed their own programs—some 58 American jurisdictions. Furthermore, each of the states except eight placed the burden on the employer to purchase insurance for employees from a private-sector purveyor. In exchange for indemnification under Workers’ Compensation Insurance, workers give up their constitutional right to sue their employer for the harm they have experienced. Workers’ Compensation Insurance is the prototype “no-fault” or “exclusive remedy” insurance.

There came into existence a new private-sector insurance industry including such pioneers as Liberty Mutual, which was founded to service the Workers’ Compensation

Insurance statutes of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Eight of the states, Ohio and Washington for example, still retain the insurance function within their own administration with varying degrees of autonomy. Furthermore, many states allow employers to “self-insure” as long as the employer meets standards in terms of size, capitalization, and administration.

Insurance statutes of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Eight of the states, Ohio and Washington for example, still retain the insurance function within their own administration with varying degrees of autonomy. Furthermore, many states allow employers to “self-insure” as long as the employer meets standards in terms of size, capitalization, and administration.

The private sector and some of the state insurance enterprises adopted the principle of actuarial-based underwriting; their premiums are calculated so that they have in hand the funds to cover the entirety of any award. If an employee is deemed totally and permanently disabled, the insurer puts “aside” (usually as working capital) sufficient funds to pay a working lifetime of pension. The companies also have the right to “experience rate” employers and industries; if any are singled out for extraordinary numbers or magnitude of claims, the premiums rise accordingly. Today, Workers’ Compensation Insurance premiums exceed 2% of the payroll nationwide, but there is tremendous variability from jurisdiction to jurisdiction and from industry to industry.11 The result is that these insurance companies can amass fortunes that they invest and dispense with relatively little government oversight.

All statutes stipulate that the injured worker is to receive all necessary medical and rehabilitative care until the worker is as well as possible. This endpoint is variously termed “maximal medical improvement,” “fixed and stable,” and, in Europe, “consolidation.” Until this endpoint is reached, the worker is also entitled to income replacement, temporary total disability (TTD) benefits. As was the case for permanent partial disability, the TTD expenditure per worker per year varies dramatically state to state. Medical care represents more than one third of the cost of these Workers’ Compensation Insurance programs. The charges billed to Workers’ Compensation Insurance carriers for medical care related to backache vary greatly from region to region but always exceed those submitted to other insurers, both public and private.12 Also, the likelihood of interventions and tests is increased for the same diagnosis if the patient is insured by Workers’ Compensation.

BACKACHE AND THE INJURY CONSTRUCT

Nearly all American Workers’ Compensation Insurance statutes define the indemnified as someone who has experienced a “personal injury … arising out of and in the course of employment.” Many stipulate that the injury occur “by accident,” which is often further defined as an “unlooked for mishap or an untoward event which is not expected or designed.” Clearly the legislators were envisioning a discrete event that could be identified in time and one that involved an element of violence. The jurisdictions were soon to be forced to contend with the concept of a discrete pathologic outcome in the absence of a violent precipitant. Consider the issues raised by claimants seeking redress for their inguinal hernia. Such a claimant can often state the work day that the hernia was first noted. The “onset” can be that discrete. Furthermore, it is often rendered more noticeable with a Valsalva maneuver, such as most use during materials handling. Does that mean that materials

handling caused the herniation? Many jurisdictions decided in the affirmative. It was this exercise in semiotics that gave birth to the term “rupture,” which all of us apply to inguinal herniation with impunity. The implication is of a violent outcome, rather than a manifestation of a congenital difference. If the outcome is so violent, the precipitant must be sufficient and the injury compensable.

handling caused the herniation? Many jurisdictions decided in the affirmative. It was this exercise in semiotics that gave birth to the term “rupture,” which all of us apply to inguinal herniation with impunity. The implication is of a violent outcome, rather than a manifestation of a congenital difference. If the outcome is so violent, the precipitant must be sufficient and the injury compensable.

This was the medicolegal framework that greeted the landmark article of Mixter and Barr in 1934.5 William Jason Mixter was a senior neurosurgeon on the staff of the Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston who had a particular interest in spinal tumors. Joseph S. Barr was his junior colleague in orthopedics. Barr was aware of the writings of the pathologist Schmorl and his associates in Heidelberg that questioned the teaching that enchondromas, chordomas, and other tumors were common in the lumbosacral spine; their reinterpretation was that the tissue represented extrusion of nucleus pulposus through the annulus fibrosus. Mixter and Barr proceeded to reproduce the pathologic observations and then to subject a series of 19 patients, most with cauda equina syndrome and myelographic evidence of encroachment, to laminectomy and fusion. The 1934 article described their results as highly positive and inferred that discal pathogenesis explained back pain in the setting of the cauda equina syndrome. One year later, Mixter and Ayer expanded the clinical correlate to backache without cauda equina syndrome.13 These articles came to capture the thinking of the American neurosurgical and orthopedic communities; elsewhere they held sway but never to the same degree. They would do so in part because the clinicopathologic correlation seems incontrovertible. It is nearly totally flawed, as discussed in Chapter 6. Furthermore, even Joseph Barr, late in his career, came to realize that the concept of discal pathogenesis explained but a portion of the illness of compensable back pain.14 But in the 1940s, there was a force more compelling than medical inference for the acceptance of the precept of discal pathogenesis.

The precept caught fire in America because the choice of terminology in these classic articles rendered acute back pain in the workplace compensable. Recall that Workers’ Compensation Insurance was and is the only universal “health” and disability insurance provided for the American worker. Once the process responsible for the backache was labeled a “rupture” of the disc, the terminology that appears in the titles of the articles and the sociopolitical consequences are not surprising. Rupture is a highly emotive term. It implies a tearing apart or rendering asunder of the disc. The implication is of horrible anatomic damage. The label has had far greater impact on the plight of those afflicted with backache than the occasional pathogenic event it is meant to describe or the surgical remediation it engendered. Starting in 1934, Americans, in particular, rapidly came to perceive regional backache as a dire illness mandating diagnosis with the promise of surgical cure.15 Concomitantly, the Workers’ Compensation Insurance establishment adopted the backache as an injury even in the absence of an insult involving external force. Particularly if the diagnosis is “ruptured disc,” it was argued, the pathologic result is such devastation that an injury must be considered causal. If the diagnostic inference of ruptured disc is putatively validated by a scar, there is little argument regarding causation.16

After World War II, the incidence of compensable backache began to escalate around the industrial world. Furthermore, surgery, indemnified by Workers’ Compensation insurers, began to escalate (although no other country managed to stay apace with the American zeal). Despite these machinations, the numbers of chronically disabled and the cost of their compensation are nothing short of astonishing. Claims data for compensable regional back “injuries” document the magnitude of the problem currently in terms of numbers of claimants and cost.17

There is another ramification of this watershed in diagnostic labeling and its rapid adoption by the Workers’ Compensation Insurance paradigm. After World War II, no one could have a backache again without wondering what they did to cause it. No physician could examine a patient with a backache, let alone a claimant, without making the inquiry, “What were you doing when it started?” And no person could have a twinge in the back without contending with the self-diagnosis of a “ruptured disc” or “slipped disc” and the anxiety that surgery and disability might be their fate. Our language and our common sense have changed. We can blithely say “I injured my back” in the absence of a violent precipitant. Before 1934 we did not have the intellectual construct to support such language; it would be as if we considered a headache a “head injury” or we talked about our pneumonia as a “lung injury.” Such descriptors remain incongruous. Yet “back injury” is comfortable and so is the medical-surgical algorithm that has evolved, underwritten by Workers’ Compensation Insurance, to become the “standard of care” despite the science (Chapter 6). This country has been so medicalized in regard to backaches that reeducation represents a pressing public health need.18

CUMULATIVE TRAUMA DISORDERS AND REPETITIVE STRAIN INJURIES

The treatment of this topic is comprehensive in the Second Edition of Occupational Musculoskeletal Disorders. This is a notion that predates the compensable regional back “injury,” having made its appearance earlier in the 20th century in the form of scrivener’s palsy and telegraphist’s wrist. It lay fallow until the 1970s when it emerged as “brachiocephalic syndrome” in Japan, and in the 1980s as repetition strain injury (RSI) in Australia, and in the 1990s as CTD in the United States. It is another example of medicalization in the context of Workers’ Compensation Insurance, in this instance the medicalization of regional arm pain rather than regional back pain. The notion is that if you use your arm repetitively, albeit in a fashion that is customary for you and customarily comfortable, you place the arm at risk for damage. The symptom of that damage is pain, and the underlying disease is the orthopedic litany from tendinitis to carpal tunnel syndrome. The science that renders this notion untenable is detailed in Chapters 6, 10 and 13 of the Second Edition of Occupational Musculoskeletal Disorders. In this edition I will not reiterate the historiography. However, there is an excellent and comprehensive monograph by Yolande Lucire devoted to that topic19 that offers a parallel and supplementary treatment of the Australian RSI epidemic to that described in the

Second Edition. RSI and CTD are malignant social constructions capable of dragging workers into the vortex of disability with the same efficiency as the compensable back “injury.” RSI has nearly disappeared from the Australian workplace, just as the brachiocephalic syndrome disappeared from the Japanese workplace. CTDs are still entrenched in the American mindset despite the relevant science that is as rich as that for the compensable back “injury.” At the policy level, the proponents of the idea of compensable arm pain have largely abandoned “CTD” as their rallying acronym. Rather, the terms “work-related upper extremity musculoskeletal disorder” or “musculoskeletal disorders” are bandied about; the latter is used in the fashion of my term “regional musculoskeletal disorders.” However, in the tradition of the compensable back “injury,” the implication is that the usage at work that is associated with symptoms is the proximate cause of the condition. Arm pain also is an intermittent and remittent predicament of life. It is disabling when coping is compromised inside or outside the workplace. Inside, psychosocial confounders are far more likely to be responsible than the physical demands of tasks. As with back pain, the science is reassuring in terms of the causal association between pathoanatomy, including carpal tunnel syndrome, and arm usage. Nonetheless, many workers with disabling regional arm pain in the United States have taken their place beside the many workers with disabling regional backache in the gauntlet we are about to consider.

Second Edition. RSI and CTD are malignant social constructions capable of dragging workers into the vortex of disability with the same efficiency as the compensable back “injury.” RSI has nearly disappeared from the Australian workplace, just as the brachiocephalic syndrome disappeared from the Japanese workplace. CTDs are still entrenched in the American mindset despite the relevant science that is as rich as that for the compensable back “injury.” At the policy level, the proponents of the idea of compensable arm pain have largely abandoned “CTD” as their rallying acronym. Rather, the terms “work-related upper extremity musculoskeletal disorder” or “musculoskeletal disorders” are bandied about; the latter is used in the fashion of my term “regional musculoskeletal disorders.” However, in the tradition of the compensable back “injury,” the implication is that the usage at work that is associated with symptoms is the proximate cause of the condition. Arm pain also is an intermittent and remittent predicament of life. It is disabling when coping is compromised inside or outside the workplace. Inside, psychosocial confounders are far more likely to be responsible than the physical demands of tasks. As with back pain, the science is reassuring in terms of the causal association between pathoanatomy, including carpal tunnel syndrome, and arm usage. Nonetheless, many workers with disabling regional arm pain in the United States have taken their place beside the many workers with disabling regional backache in the gauntlet we are about to consider.

THE GAUNTLET OF THE WORKERS’ COMPENSATION INSURANCE CLAIM FOR REGIONAL BACK PAIN

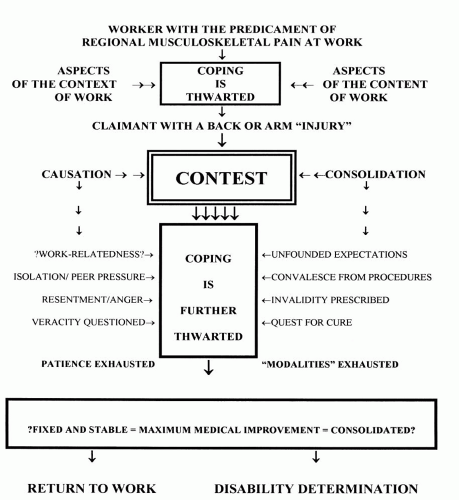

Whenever a worker chooses to be a claimant for a regional musculoskeletal disorder, a contest ensues (Fig. 12.1). If the worker can and does return to work rapidly, the contest is fleeting, often subliminal. Some 10% to 20% will be faced with prolonged disability. No single feature predicts this fate.20 Rather, a complex mélange of features of the job as well of the worker can be discerned.21, 22, 23 There is even the suggestion that having a spouse or other primary family member on the disability rolls is a risk factor.24 Although all this complexity may be challenging for epidemiology, it is less so for the claimant; somehow the claimant “knows” because the claimant’s auguring is highly reliable.25 For the 10% or so whose pain and disability are relentless, the contest can be brutal. It is fought over the three contentious clinical decision nodes inherent to the Workers’ Compensation Insurance paradigm. The aspects of work that compromise coping and predispose to the claim were discussed in Chapters 2 and 10. The first of the contests, the contest of causation, was the focus of Chapter 11. Here we will focus on the contest of consolidation and the fate of disability determination.

THE CONTEST OF CONSOLIDATION

If you have acquired the illness of work incapacity in the context of a backache, Workers’ Compensation Insurance is the most appealing recourse generally available in our society. Your medical care is underwritten, and you will not experience income loss while you are healing. Too many working Americans, more than one third, have no other coverage. The majority have some form of health insurance. But nearly every health insurance policy places limits on the quantity of medical care it covers, and few, if any, fully indemnify wage loss. Rather, one has “sick leave” to fall back on until it runs out. No wonder any ill worker should consider whether the illness qualifies for coverage under Workers’ Compensation Insurance. It is no wonder that regional backache found a niche in Workers’ Compensation Insurance coverage and occupies this niche with the greatest of tenacity on the part of labor and providers of care in most industrialized countries. The exception is Japan, where peer pressure coupled with comparability in entitlement predisposed the worker with a disabling backache to seek recourse under health and disability insurance rather than Workers’ Compensation Insurance.26

Thanks to Mixter and Barr,5 establishing this niche was not hard fought. However, occupying it is. Becoming a Workers’ Compensation claimant with a regional backache is to expose oneself to a medical gauntlet. You are not forewarned. Most claimants regain health rapidly and escape relatively unscathed.27 But a few of these sink into the contest. These few represent less than 10% of all Workers’ Compensation claimants for back and arm “injuries,” yet the contests and their consequences consume some 90% of the direct costs of the entire Workers’ Compensation Insurance program.

The contest of causation contributes to these costs by virtue of administrative and legal overhead. However, there is a more insidious contest that plays out between the provider of care and the claimant. I call it the contest of consolidation, borrowing the European term for “fixed and stable” or “maximum medical improvement,” which are the terms more familiar to Americans. Workers’ Compensation Insurance is designed to pay for all interventions that will get the patient well enough to return to work as rapidly as possible. This is the engine that drives the contest. It is coupled to the presumptions that the cause of the back (or arm) “injury” can be defined and, once defined, cured. The contest plays out under the banner of getting well as soon as possible and therefore deludes all the participants.

Whenever a patient with acute regional low back pain is accepted for treatment as a claimant with an acute back injury, both the claimant and the practitioner commence the hunt for the cause. The history of the “event” and prior episodes are detailed as part of the contest of causation. Physical examinations are undertaken, oftentimes in exhaustive detail, to define the extent of instability, the presence of radiculopathy, the compromise in mobility, and other “signs” believed to be interpretable. And always there is the recommendation for imaging: plane films, computed tomography scans, and magnetic resonance imaging are accepted as routine by physicians, claimants, and insurers.28 The “great technologic advance” of imaging the American back by magnetic resonance imaging is estimated to have added billions to the cost of diagnosis and treatment, much indemnified by Workers’ Compensation Insurance and all to no avail.29 And while these tests and others are underway, the claimant is exposed to a potpourri of interventions. The array of diagnostic procedures and remedies offered the patient with backache in all

western countries is a testimony to the inventiveness of medical and nonmedical practitioners. Much of this enterprise is underwritten by Workers’ Compensation Insurance. As detailed in Chapter 7, most of the diagnoses are improvable, most of the remedies are unproved, and some are even proven to be without benefit.30,31 Yet the enterprise thrives. Why? Why did the rate of cervical and lumbar spine surgery escalate in the United States between 1979 and 1990?32 Why is there such great geographic variation in these rates of surgery in the United States?33 Surely, no one would argue that all this activity and expense advantages the claimant with a compensable back “injury” when compared with the patient with a regional backache?34

western countries is a testimony to the inventiveness of medical and nonmedical practitioners. Much of this enterprise is underwritten by Workers’ Compensation Insurance. As detailed in Chapter 7, most of the diagnoses are improvable, most of the remedies are unproved, and some are even proven to be without benefit.30,31 Yet the enterprise thrives. Why? Why did the rate of cervical and lumbar spine surgery escalate in the United States between 1979 and 1990?32 Why is there such great geographic variation in these rates of surgery in the United States?33 Surely, no one would argue that all this activity and expense advantages the claimant with a compensable back “injury” when compared with the patient with a regional backache?34

While this contest is playing out, “the culprit” is proscribed. After all, because usage on the job is held to be the cause of the accident, it must be avoided. Furthermore, the financial issue is removed from the worker in the form of income substitution, the TTD benefit. From the outset, and by contract, the clinical evaluation is disabling.

Unfortunately, too few individuals have normal imaging study results. Unconscionably, too few physicians and chiropractors are willing to discount a “finding,” particularly if the patient is a Workers’ Compensation Insurance claimant. Rather, the findings are interpreted as consistent with the practitioner’s preconceived notions of pathogenesis. If it appears manipulable or operable, the claimant and the insurer are informed. Furthermore, the implicit or explicit advice is that the claimant would be unlikely to heal without the intervention purveyed. Hence, Workers’ Compensation Insurance is expected to underwrite the extraordinary enterprise that waits on the American back injury. And it does.

As was made clear in Section II, the clinical history, details of the physical examination, imaging modalities, and even specialized electrodiagnostic studies to assess muscle recruitment are all fraught with inadequacies in specificity, sensitivity, predictive value, and accuracy. They are so fraught that they offer more obfuscation than enlightenment and clearly generate more anxiety than they are worth. In addition, whoever is orchestrating the “diagnostic workup” generally has a limited therapeutic armamentarium in hand, if not in mind. (When you have a hammer, all the world seems a nail. Sic!) In the hands of the surgeon, surgery is all too ready an option. In the hands of the chiropractor, manipulation seems appropriate to try. Others advocate drugs, still others advocate rest, and others advocate various forms of exercise. There is no difference in the likelihood of getting well, only in the costliness. Woe is to the claimant who does not get well. If one modality does not work, another will be tried. In fact, each practitioner will exercise his or her trade until it is exhausted and then, if the claimant is not back to work, blame the claimant. This is the implication of such terms as “the failed back” used by surgeons to impugn the personality of the claimant rather than their own judgment.35

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree