The neuromuscular medicine and physiatry specialists are key health care providers who work cooperatively with a multidisciplinary team to provide coordinated care for individuals with neuromuscular diseases (NMDs). The director or coordinator of the team must be aware of the potential issues specific to NMDs and be able to access the interventions that are the foundations for proper care in NMD. Ultimate goals include maximizing health and functional capacities, performing medical monitoring and surveillance to inhibit and prevent complications, and promoting access and full integration into the community to optimize quality of life.

- •

Both neuromuscular medicine specialists and physiatrists are key health care providers who work cooperatively with a multidisciplinary team to provide coordinated care for individuals with neuromuscular diseases (NMDs).

- •

Ongoing input from different specialties is important because the specific assessments and interventions that are necessary will change as the NMD progresses.

- •

Addressing the many complications of NMDs in a comprehensive and consistent way is also crucial for planning and determining eligibility for clinical trials and for improving care worldwide.

- •

The development and implementation of standardized care recommendations for NMDs will lead to improved health, function, participation, and quality of life.

The estimated total prevalence of the most common NMDs in the United States is 500,000. Combined with all forms of acquired NMDs, the prevalence exceeds 4 million, which is an impressive figure when compared, for example, with the prevalence of spinal cord injury, which is estimated to be between 239,000 and 306,000. There is tremendous diversity of the causes for both acquired and hereditary NMDs. Some NMDs are acquired with diverse causes distinct from genetic causes, such as autoimmune, infectious, metabolic, toxic, or paraneoplastic (eg, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [ALS], myasthenia gravis, Lambert-Eaton syndrome, botulism, Guillain-Barré syndrome, or diabetic peripheral neuropathy). There are more than 500 distinct NMDs identified to date that have specific genes that have been linked causally to these conditions. Limb girdle muscular dystrophy, for example, has more than 20 genetically distinct subtypes that have been identified to date. The genetic heterogeneity of hereditary NMDs has created challenges for clinicians and researchers.

Although currently incurable, NMDs are not untreatable. The neuromuscular medicine and physiatry specialists are key health care providers who work cooperatively with a multidisciplinary team to maximize health; maximize functional capacities, including mobility, transfer skills, upper limb function, and self-care skills; inhibit or prevent complications, such as disuses weakness, skeletal deformities, disuses weakness, airway clearance problems, respiratory failure, cardiac insufficiency and dysrhythmias, bone health problems, excessive weight gain or weight loss, metabolic syndrome; and promote access to full integration into the community with optimal quality of life.

The molecular basis of hereditary NMDs has been emerging and coming into sharper focus over the past 3 decades. Many promising therapeutic strategies have since been developed in animal models. Human trials of these strategies have started, leading to the hope of definitive treatments for many of these currently incurable diseases. Although specific treatments for NMDs have not yet reached the clinic, the natural history of these diseases can be changed by targeting interventions to known manifestations and complications. The diagnosis can be swiftly reached, families and patients can be well supported, and individuals who have NMDs can reach their full potential in education and employment. In Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), for example, corticosteroid, respiratory, cardiac, orthopedic, and rehabilitative interventions have led to improvements in function, quality of life, health, and longevity, with children who are diagnosed today having the possibility of a life expectancy into their fourth decade.

Advocacy organizations report variable and inconsistent health care for individuals with NMD. Although anticipatory and preventive clinical management of NMDs is essential, recommendations exist in only a few areas. Addressing the many complications of NMDs in a comprehensive and consistent way is also crucial for planning multicenter trials and for improving care worldwide. The development and implementation of standardized care recommendations have been emphasized by stakeholders in heterogeneous NMD communities, including government agencies, clinicians, scientists, academicians, volunteer health agencies, and advocacy organizations. The purpose of this issue is to provide a framework for recognizing the primary manifestations and possible complications and for planning the optimum treatment across different specialties with a coordinated multidisciplinary team.

Reported needs of individuals with NMDs

The greatest needs of the population of individuals with NMDs were recently evaluated by the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research–funded Rehabilitation Research and Training Center in NMDs at the University of California (UC) Davis Medical Center. The authors performed a comprehensive quality-of-life survey of more than 1000 individuals with NMDs. The most frequent problems impacting quality of life in NMDs are shown in Table 1 . Consumers with NMDs reported that the most significant problems impacting their health, function, and quality of life were secondary conditions, including weakness, fatigue and poor endurance, weight management, sleep disturbances, muscle contractures, and breathing problems. These problems translate into functional issues that consumers with NMDs note to be significant, such as difficulty walking, exercising, controlling weight, and doing activities of daily living (ADLs).

| How Much Difficulty Do You Have Performing the Following Functions? | Moderate or Severe (%) | Slight (%) | Not a Problem (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Difficulty with muscle weakness | 72.4 | 11.6 | 6.0 |

| Difficulty getting exercise | 66.1 | 17.5 | 16.3 |

| Difficulty with fatigue | 70.8 | 21.7 | 7.6 |

| Difficulty controlling weight | 36.0 | 27.9 | 36.2 |

| Difficulty with sleeping | 36.2 | 28.6 | 35.1 |

| Difficulty with muscle contractures | 33.6 | 29.9 | 36.6 |

| How Much Does Your Health Limit You in the Following Activities? | A Lot (%) | A Little (%) | Not at All (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vigorous activities, such as running | 93 | 3 | 4 |

| Walking more than a mile | 84 | 9 | 7 |

| Walking several blocks | 73 | 17 | 10 |

| Walking one block | 54 | 27 | 18 |

The Multidisciplinary NMD team

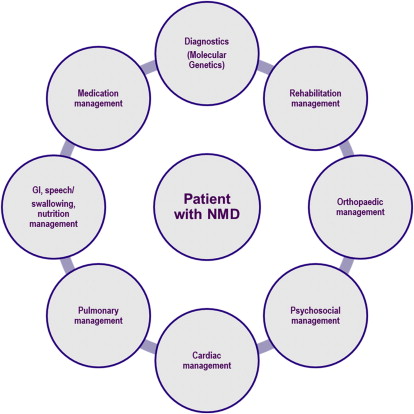

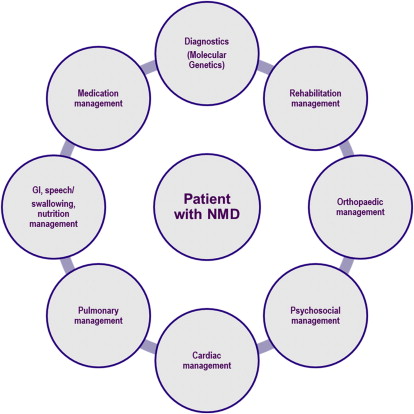

The comprehensive management of all of the varied clinical problems associated with NMDs is a complex task. For this reason, the multidisciplinary or interdisciplinary approach is critical. The two terms are often used interchangeably with inter-discipline communication being the key. It takes advantage of the expertise of many clinicians rather than placing the burden on one. This interdisciplinary approach to caring for patients with NMD, and participation by committed providers that have NMD-specific expertise are key ingredients to the provision of optimal care ( Fig. 1 ). Patients and families/care providers should actively engage with the medical professional who coordinates clinical care. Depending on the patient’s circumstances, such as area/country of residence or insurance status, this role might be served by, but is not limited to, a neurologist or pediatric neurologist, physiatrist/rehabilitation specialist, neurogeneticist, pediatric orthopedist, pediatrician, or primary care physician. In the United States, the neuromuscular medicine specialist often does the coordination of care (fellowships in neuromuscular medicine approved by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education now exist for subspecialty certification within the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology and the American Board of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation). The director or coordinator of the team must be aware of the potential issues specific to NMDs and be able to access the interventions that are the foundations for proper care in NMD. These foundations include health maintenance and proper monitoring of disease progression and complications to provide anticipatory, preventive care, and optimum management.

NMD management is best performed by a team consisting of physicians; physical, occupational, and speech therapists; social workers; vocational counselors; and psychologists, among others. Ideally, owing to the significant mobility problems associated with most NMDs, the neuromuscular medicine specialist, physiatrist, and all the key clinical personnel should be available at each visit. Tertiary care medical centers in larger urban areas usually can provide this type of service. This may be an independent clinic or may be sponsored by one or more of the consumer-driven organizations that sponsor research and clinical care for people with NMDs, including the Muscular Dystrophy Association, the Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Association, the Charcot-Marie-Tooth International and Association groups, and the Facioscapulohumeral Society, among others. Although the physiatrist (Greek for physis for “nature” and iatrikos for “healing”) is well suited to direct the rehabilitation team and to oversee a comprehensive, goal-oriented treatment plan, physiatrists are the codirectors of less than 20% of the MDA clinics in the United States and a recent MDA Clinic Directors survey showed that fewer than one-half of MDA Clinics have a physiatrist as a member of the multidisciplinary team. Bach has previously described the many major advances physiatrists have contributed to the care of patients with NMD and has pointed out the rather significant need for more physiatric involvement in the care of these patients.

Toolkits of Assessments and Interventions for the Interdisciplinary NMD Team

There are varied toolkits of assessments and interventions applicable to NMD management ( Table 2 ). Input from different specialties and the specific assessments and interventions will change as the NMD progresses. Some measures, such as strength assessment, functional grading, timed function measures, and pulmonary function measures, are core measures performed at least annually for most NMDs. Others are performed regularly depending on the expected impairments for specific NMDs.

| Multidisciplinary Domains | Tools/Assessments | Interventions |

|---|---|---|

| Diagnostics (neuromuscular medicine specialist, geneticist, pathologist) | Biomarkers (eg, creatine kinase) Electrodiagnostics Molecular genetics Muscle biopsy | Genetic counseling Family support |

| Medication management (neuromuscular medicine specialist, neurodevelopmental pediatrician, physiatrist) | Clinical evaluation Strength Function Range of motion | Considerations Age of patient Stage of disease Risk factors for side effects Available medications Choice of regimen Side-effect monitoring and prophylaxis Dose alteration |

| Rehabilitation management | Range of motion Strength Posture Function Alignment Gait | Stretching Positioning Splinting Orthoses Submaximum exercise/activity Seating Standing devices Adaptive equipment Assistive technology Strollers/scooters Manual/power wheelchairs |

| Orthopedic management | Assessment of range of motion Spinal assessment Spinal radiograph Bone age (left wrist and hand radiograph) Bone densitometry | Tendon surgery Osteotomies/arthrodesis Posterior spinal fusion |

| GI, speech/swallowing, nutrition management | Upper and lower GI investigations Anthropometry | Diet control and supplementation Gastrostomy Pharmacologic management of gastric reflux and constipation |

| Pulmonary management | Spirometry Static airway pressures (MIP/MEP) Peak cough flow Pulse oximetry Capnography/end tidal carbon dioxide ABG Sleep studies/polysomnography | Volume recruitment Noninvasive ventilation (via mask and nasal interfaces) Invasive ventilation (via tracheostomy) Airway clearance (Cough Assist Mechanical Insufflator-Exsufflator [Phillips Respironics, Andover, MA, USA], The Vest Airway Clearance System (Hill-Rom, St. Paul, MN, USA) Immunizations |

| Cardiac management | ECG Echo Holter Cardiac MRI | ACE inhibitors Angiotensin receptor blockers β blockers Diuretics Inotropes Other heart failure medication Antiarrhythmics |

| Psychosocial management | Coping Neurocognitive Speech and language Autism Social work | Psychotherapy Pharmacologic interventions Social support Educational support Palliative/Supportive care |

The Multidisciplinary NMD team

The comprehensive management of all of the varied clinical problems associated with NMDs is a complex task. For this reason, the multidisciplinary or interdisciplinary approach is critical. The two terms are often used interchangeably with inter-discipline communication being the key. It takes advantage of the expertise of many clinicians rather than placing the burden on one. This interdisciplinary approach to caring for patients with NMD, and participation by committed providers that have NMD-specific expertise are key ingredients to the provision of optimal care ( Fig. 1 ). Patients and families/care providers should actively engage with the medical professional who coordinates clinical care. Depending on the patient’s circumstances, such as area/country of residence or insurance status, this role might be served by, but is not limited to, a neurologist or pediatric neurologist, physiatrist/rehabilitation specialist, neurogeneticist, pediatric orthopedist, pediatrician, or primary care physician. In the United States, the neuromuscular medicine specialist often does the coordination of care (fellowships in neuromuscular medicine approved by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education now exist for subspecialty certification within the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology and the American Board of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation). The director or coordinator of the team must be aware of the potential issues specific to NMDs and be able to access the interventions that are the foundations for proper care in NMD. These foundations include health maintenance and proper monitoring of disease progression and complications to provide anticipatory, preventive care, and optimum management.

NMD management is best performed by a team consisting of physicians; physical, occupational, and speech therapists; social workers; vocational counselors; and psychologists, among others. Ideally, owing to the significant mobility problems associated with most NMDs, the neuromuscular medicine specialist, physiatrist, and all the key clinical personnel should be available at each visit. Tertiary care medical centers in larger urban areas usually can provide this type of service. This may be an independent clinic or may be sponsored by one or more of the consumer-driven organizations that sponsor research and clinical care for people with NMDs, including the Muscular Dystrophy Association, the Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Association, the Charcot-Marie-Tooth International and Association groups, and the Facioscapulohumeral Society, among others. Although the physiatrist (Greek for physis for “nature” and iatrikos for “healing”) is well suited to direct the rehabilitation team and to oversee a comprehensive, goal-oriented treatment plan, physiatrists are the codirectors of less than 20% of the MDA clinics in the United States and a recent MDA Clinic Directors survey showed that fewer than one-half of MDA Clinics have a physiatrist as a member of the multidisciplinary team. Bach has previously described the many major advances physiatrists have contributed to the care of patients with NMD and has pointed out the rather significant need for more physiatric involvement in the care of these patients.

Toolkits of Assessments and Interventions for the Interdisciplinary NMD Team

There are varied toolkits of assessments and interventions applicable to NMD management ( Table 2 ). Input from different specialties and the specific assessments and interventions will change as the NMD progresses. Some measures, such as strength assessment, functional grading, timed function measures, and pulmonary function measures, are core measures performed at least annually for most NMDs. Others are performed regularly depending on the expected impairments for specific NMDs.

| Multidisciplinary Domains | Tools/Assessments | Interventions |

|---|---|---|

| Diagnostics (neuromuscular medicine specialist, geneticist, pathologist) | Biomarkers (eg, creatine kinase) Electrodiagnostics Molecular genetics Muscle biopsy | Genetic counseling Family support |

| Medication management (neuromuscular medicine specialist, neurodevelopmental pediatrician, physiatrist) | Clinical evaluation Strength Function Range of motion | Considerations Age of patient Stage of disease Risk factors for side effects Available medications Choice of regimen Side-effect monitoring and prophylaxis Dose alteration |

| Rehabilitation management | Range of motion Strength Posture Function Alignment Gait | Stretching Positioning Splinting Orthoses Submaximum exercise/activity Seating Standing devices Adaptive equipment Assistive technology Strollers/scooters Manual/power wheelchairs |

| Orthopedic management | Assessment of range of motion Spinal assessment Spinal radiograph Bone age (left wrist and hand radiograph) Bone densitometry | Tendon surgery Osteotomies/arthrodesis Posterior spinal fusion |

| GI, speech/swallowing, nutrition management | Upper and lower GI investigations Anthropometry | Diet control and supplementation Gastrostomy Pharmacologic management of gastric reflux and constipation |

| Pulmonary management | Spirometry Static airway pressures (MIP/MEP) Peak cough flow Pulse oximetry Capnography/end tidal carbon dioxide ABG Sleep studies/polysomnography | Volume recruitment Noninvasive ventilation (via mask and nasal interfaces) Invasive ventilation (via tracheostomy) Airway clearance (Cough Assist Mechanical Insufflator-Exsufflator [Phillips Respironics, Andover, MA, USA], The Vest Airway Clearance System (Hill-Rom, St. Paul, MN, USA) Immunizations |

| Cardiac management | ECG Echo Holter Cardiac MRI | ACE inhibitors Angiotensin receptor blockers β blockers Diuretics Inotropes Other heart failure medication Antiarrhythmics |

| Psychosocial management | Coping Neurocognitive Speech and language Autism Social work | Psychotherapy Pharmacologic interventions Social support Educational support Palliative/Supportive care |

The World Health Organization International Classification of Functioning framework

Although their degrees and severity can vary, the characteristics or complications of most NMDs include progressive weakness, limb contractures, spine deformity, and decreased pulmonary function; some patients suffer cardiac and intellectual impairment. In determining the severity of impairment and disability, a comprehensive evaluation of patients with NMDs should be done at routine intervals or as clinically indicated. The World Health Organization’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) provides a useful framework for evaluating the manifestations and complications of NMDs. The bioecological ICF framework incorporates domains covering body structure and function, individual activities and participation, and environmental factors that impact the overall physical and mental health of the individual in a societal context. In this framework, body structures are anatomic parts of the body, such as organs, limbs, and their counterparts, and body functions are the physiologic functions of body systems, including physiologic functions. Impairments are problems in body structure or body function as a significant deviation from normal or loss. Activity is the execution of a task or action by an individual, and activity limitations are difficulties an individual may have in executing activities. Participation is the involvement in a life situation, and participation restrictions are problems an individual may have in the involvement in life situations. Although the ICF framework covers environmental domains, such as external barriers to participation, the authors typically do not include assessments of environmental domains of the ICF framework because of the limited ability of therapeutic agents, surgeries, or rehabilitation interventions evaluated in clinical trials to impact these domains.

Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) encompass self-perceived or caregiver-proxy–perceived concepts of health and well-being defined broadly including such concepts as health-related quality of life, satisfaction, physical functioning, basic mobility and transfers, sports and physical functioning, mobility and ambulation, upper extremity functioning and ADLs, pain, fatigue, quality of sleep, emotional health, social health, depression, anxiety, stigma, and so forth.

Selected assessments for NMD

There are diverse assessments that are performed in NMDs for clinical studies, natural history studies, and clinical trials. For example, Table 3 summarizes the diverse nature of clinical endpoints and assessments that have been used clinically and in natural history studies involving individuals with DMD organized according to a modified ICF framework. Some core measures, such as manual muscle testing for strength, range of motion (ROM), timed function, pulmonary function, and selected cardiac measures, are routinely performed annually or more frequently if clinically indicated.

| Body Structure/Function | |

|

|

| Activities (Clinical Evaluator-Determined Scales) | |

|

|

| Activities (Functional Tests with Timed Dimension) | |

|

|

| Participation measures | |

|

|

| Patient-reported outcome measures | |

|

|

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree