Abstract

Objective

The objective of the present study was to highlight the role of head stabilization and to analyze multisegment head-trunk coordination during gait in children with cerebral palsy (CP).

Material and method

Postural control was measured and compared in a group of 16 CP subjects and a control group of 16 healthy subjects. The subjects had to walk along an out-and-back course at their freely chosen gait speed. For each gait cycle, motion analysis techniques were used to calculate the amplitude of the head angle (relative to the trunk) in the sagittal and frontal planes.

Results

Kinematic analysis revealed a number of significant intergroup differences, with a more pronounced variation in the head angle (relative to the trunk) in the CP group than in the control group. There were no significant intergroup differences in terms of the angular amplitude of the head in the sagittal plane.

Conclusion

The greater variability of the head angle in the frontal plane in the CP subjects might reflect the presence of greater head roll as a compensatory strategy. These finding suggest that the clinical evaluation of posture during gait in children with CP should be reconsidered.

Résumé

Objectifs

L’objectif de cette étude était de mettre en évidence le rôle éventuel de la stabilisation de la tête et d’analyser les coordinations multisegmentaires entre la tête et le tronc lors de la marche chez des enfants atteints de paralysie cérébrale (PC).

Matériel et méthode

Un groupe de 16 sujets PC a été comparé à un groupe témoin de 16 sujets sains afin de quantifier d’éventuelles stratégies différentes dans le contrôle postural dans une tâche de locomotion. Les sujets devaient réaliser en marchant à vitesse spontanée des aller-retours sur une distance de 10 m. Les méthodes d’analyse du mouvement ont permis de calculer pour chaque cycle de marche les amplitudes maximales et minimales des angles de la tête par rapport au tronc dans les plans sagittal et frontal.

Résultats

L’analyse des données cinématiques montre des différences significatives avec notamment une variabilité de l’angle de la tête par rapport au tronc plus marquée chez les sujets PC dans le plan frontal. On ne constate aucune différence significative au niveau des amplitudes angulaires de la tête dans le plan sagittal.

Conclusion

Les deux groupes stabilisent la tête dans le plan sagittal. Dans le plan frontal, la variabilité des données traduirait la présence d’un roulis plus marqué chez les sujets PC leur permettant probablement de développer des stratégies de compensation afin d’atténuer les conséquences de leur atteinte. Cela permettrait de reconsidérer cliniquement l’organisation posturale globale des enfants PC dans la production de la marche.

1

English version

1.1

Introduction

Gait is a complex process characterized by rhythmic, cyclic, alternating movements of the legs and arms. However, gait also requires the movement of other body segments, since the single- and dual-stance actions of the legs are associated with slight rotations of the head and the trunk around the anteroposterior and mediolateral axes . Analysis of these rotations can reveal the organizational and motor strategies used by the central nervous system (CNS) to minimize destabilizing translations of the trunk during gait .

According to some researchers , the body can be considered as a multi-articulated system that is coordinated by the CNS during the production of movements or displacements. This raises the problem of the control mechanism needed to stabilize one or more body segments, that is to say a stable frame of reference against which posture is organized. The choice of this frame of reference is therefore critical for postural control.

Several studies have shown that on the behavioural level, stabilization of the head’s position in space is one of the motor strategies used to establish a stable frame of reference in balance control during movement. This involves three categories of sensory receptors, each of which is stimulated during gait:

- •

the visual system collects exteroceptive information that provides the subject with a stable frame of reference and enables stabilization of the visual field;

- •

vestibular sensors provide the CNS with feedback on the head’s angular and linear accelerations;

- •

proprioceptive receptors in the neck’s muscles and spinal joints provide information on the displacement of the head with respect to the trunk and the spatial frame of reference. This multimodal sensory system means that the head can be considered as a true frame of reference for spatial orientation.

Intersensory coordination enables the subject to estimate the position of his/her body in space as a function of the context and the task to be performed .

In the child, balance control and independent gait develop with motor learning, as the body ages and the structures involved mature . Gait is thus both an ontogenetic process and the product of a learning process that is generally interpreted as a marker of the child’s physical and neurological integrity . In fact, gait requires certain levels of bone strength, muscle tone and CNS maturity. Head stabilization is a motor skill that takes quite a while to master; it is only around the age of 9 that the child is able to free up the head-trunk joint complex, stabilize the head in space and thus better exploit visual and vestibular information for balance control . The child thus develops increasing complex balance strategies as it matures, each of which involves different segmental stabilization phases.

However, in a condition like cerebral palsy (CP), gait and the postural control are impaired to a degree that depends on the site and extent of the brain damage. Non-hereditary CP results from central neurological lesions that affect the fast-maturing brain (i.e. before or during birth or up until the age of around 3). The brain damage causes primary (mainly motor) impairments, which translate into a set of persistent movement and postural disorders (spasticity, muscle tone disorders, balance disorders, etc.). Moreover, various bone and muscle malformations (secondary anomalies) appear during growth; these mainly affect the legs and the trunk and often oblige the child to adopt a stooped posture that greatly complicates gait. The child’s gait is then accompanied by:

- •

significant postural instability and joint rigidity caused by spasticity and ataxia;

- •

thus a reduction in the body’s joint-related degrees of freedom .

In many cases, these disorders prevent efficient gait.

To the best of our knowledge, the only study of head stabilization during normal gait on a treadmill in children suffering from spastic CP showed that only the variability in the amplitude of head displacements differed with respect to a control group of healthy children .

The primary objective of the present study was to characterize postural control during gait in children suffering from CP and thus to observe and quantify possible differences in the organisation and the control of head stabilization (relative to healthy controls). Our starting hypothesis was that head stabilization would be perturbed in the CP group, which would oblige these children to develop compensatory gait strategies.

1.2

Materials and methods

1.2.1

The study population

A total of 32 boys and girls over the age of 9 participated in the study. All had to be able to walk at least 60 m and were free of comprehension and vision disorders. We studied a group of 16 children suffering from CP (mean ± SD age: 11 ± 1.2) and a group of 16 healthy children with no apparent neurological, muscle or joint disorders (mean age: 11 ± 1.5). This retrospective study was performed as part of a quantitative gait analysis.

1.2.2

Study procedures

Participants were equipped with 34 retroreflective markers, in accordance with a strict protocol : four on the head, five on the trunk, five on each arm, three on the pelvis and six on each leg. This arrangement enables reconstruction of the segmental axes and thus the various joint centres with respect to each other, in order to quantify kinematic and joint-related variables.

The participants had to walk along a 10 m gait track (width: 60 cm) delimited by a dark colour on the floor. Each participant performed six out-and-back trips at his/her freely chosen gait speed.

1.2.3

Material

In order to collect kinematic data, we used a VICON ® optoelectronic movement capture system (Oxford Metrics, Oxford, UK) with eight infrared cameras and a sampling frequency of 200 Hz.

1.2.4

Data processing

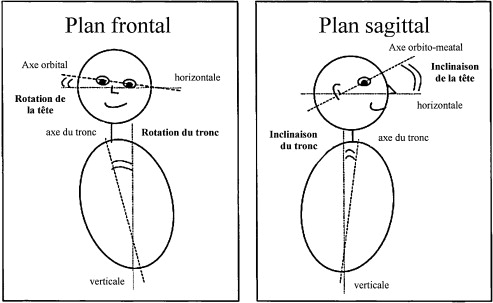

Data from the optoelectronic system was first processed with VICON-Nexus ® acquisition software (Oxford Metrics), in order to reconstruct the markers’ positions in three dimensions, time-stamp the various locomotor events (notably foot-floor contacts, such as foot-on and toe-off) for each foot, define the individual gait cycles and create 3D files. Next, the datasets were processed with Motion Inspector ® software (Biometrics France, Orsay, France), in order to analyze the various angular displacements of the head and trunk segments in space. In the present study, we only analysed the maximum and minimum amplitudes (calculated for each gait cycle) of the head angle, relative to the orbitomeatal and horizontal axes (i.e. head pitch and head roll, respectively) and the trunk. These measurements correspond to the coordination of the head-trunk joint complex in the sagittal and frontal planes (trunk pitch and trunk roll).

1.2.5

Statistical analysis

After having checked that each variable was normally distributed (according to a Shapiro-Wilk test), we used R software to compare the two groups in an analysis of variance (ANOVA). The threshold for statistical significance was set to P < 0.05 in all cases. Moreover, spontaneous gait speed (0.92 ± 0.30 m/s and 1.18 ± 0.10 m/s for the CP and control groups, respectively) was considered as an exploratory variable in the ANOVA.

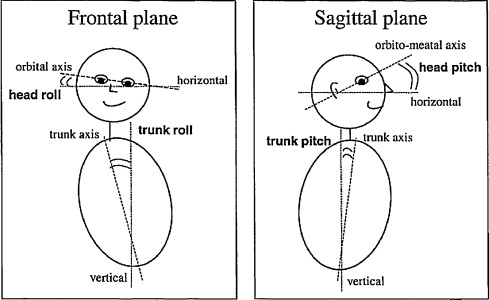

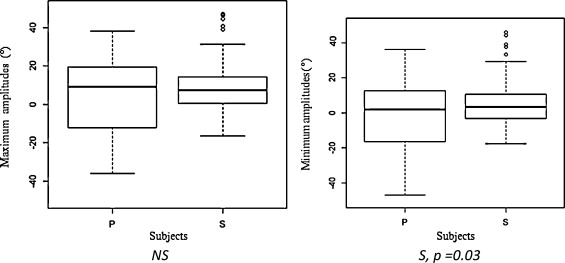

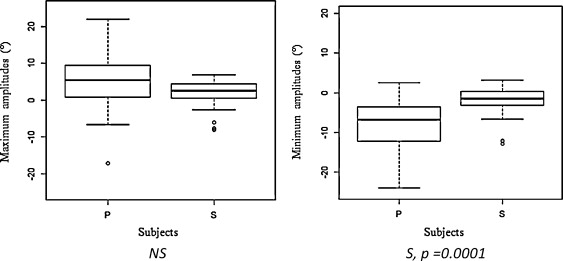

The results were represented by box-and-whisker plots that depict the median values, dispersion and range for each population and show whether the data are normally distributed or not.

The scale for each variable is given on the vertical axis. The box-and-whisker plots indicate five different values:

- •

the minimum value;

- •

the 1st quartile (25% of the sample, represented by the lower edge of the box);

- •

the 2nd quartile (50% of the sample, represented by the horizontal line inside the box);

- •

the 3rd quartile (75% of the sample, represented by the upper edge of the box) and (v) the maximum value. The minimum and maximum values are represented by circles situated beyond the 1st and 3rd quartiles.

1.3

Results

The maximum and minimum angular amplitudes of the head and trunk in the sagittal and frontal planes are presented in Fig. 1 .

1.3.1

Amplitudes in the sagittal plane

There were no statistically significant differences between the CP and control groups in terms of the maximum and minimum head angle amplitudes in the sagittal plane (relative to the vertical). High inter-individual variability was noted in the two groups; for example, the mean ± SD maximum amplitude was –2.95° ± 20.25 in the CP group and –7.86° ± 16.40 in the control group. However, our statistical analysis of the head angle relative to the trunk ( Fig. 2 ) revealed significant intergroup effects for the minimum angular amplitude only (–0.37° ± 21.86 and 6.31° ± 14.95 in the CP and control groups, respectively).

1.3.2

Amplitudes in the frontal plane

The CP and control groups only differed significantly in terms of the minimum amplitude of the head angle relative to the vertical ( Fig. 3 ) (–7.52° ± 5.26 and –1.79° ± 3.38, respectively) and relative to the trunk (–8.61° ± 7.01 and –2.05° ± 3.87, respectively) ( Fig. 4 and Table 1 ).

| Head angle, ralative to the vertical | Head angle, relative to the trunk | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum amplitude | Minimum amplitude | Maximum amplitude | Minimum amplitude | |

| Children with CP | 6.16° ± 11.94 | –7.52° ± 5.26 | 6.28° ±1 2.93 | –8.61° ± 7.01 |

| Control children | 4.10° ± 12.93 | –1.79° ± 3.38 | 3.71° ± 12.87 | –2.05° ± 3.87 |

1.4

Discussion

1.4.1

Amplitudes in the sagittal plane

The absence of significant CP versus control differences in the amplitudes of the head angle (relative to the vertical) may be due to the fact that the children in both groups tended to look forwards and downwards, i.e. at the area on which they were walking or about to walk . This finding is in agreement with work by Berthoz , who described this particular orientation of the head and the gaze during locomotor activity. By planning the trajectory, the subjects in each group were trying to move forward safely and fulfil the demands of the task (i.e. not straying over the boundaries of the gait track, which was only 60 cm wide).

By minimizing head roll, the subjects in the two groups implemented a common strategy for seeking a stable frame of reference. This enabled them to move the body forward by expending as little energy as possible, maximizing postural stability and reducing horizontal and vertical displacements of the head. This head stabilization favours what Paillard referred to as “positional anchoring” of the gaze – a fundamental component of the vestibulo-ocular balance process.

This overall strategy was confirmed by our observations of the head angle values (relative to the trunk) with a general tendency in both groups to place the chin as close to the chest as possible. This testifies to a strategy in which a reduction in the number of degrees of freedom enables better postural control. However, the difficulties in gait production encountered by the CP subjects appear to underlie the significant difference in head angle values (relative to the trunk) between the two groups ( Fig. 2 ). It appears to be difficult (or indeed impossible, in some cases) for children with CP to dissociate rotations of the head from those of the trunk. The CP subjects displayed an “en bloc” organisational strategy in which the head and the trunk moved as a single segment.

1.4.2

Amplitudes in the frontal plane

The two groups only differed significantly in terms of the minimum amplitude of the head angles (relative to the vertical and the trunk). The absence of a significant difference between the respective maximum amplitudes may have been due to the high inter-individual variability observed in each of the two groups.

We consider that the significant difference in minimum amplitude can be explained by the presence of more marked head roll in the CP group. As mentioned above, the latter children performed “en bloc” gait. After throwing the arm forwards, the subject performed a gripping action of the hand — as if the subject was seeking a handhold in empty space for pulling the body forwards. This “en bloc” organisational strategy probably explains why the amplitudes of displacement in the frontal plane were greater in the CP subjects. Together with a skipping approach that helps to bring the swing foot forward, this “en bloc” movement is part of a general attempt to walk efficiently and compensate for motor impairments.

1.5

Conclusion

The aim of the present pilot study was to characterize postural control during gait in children (aged between 10 and 12) with CP and thus to compare and quantify potential differences in the organisation and control of head stabilization with respect to control participants of a similar age.

Our starting hypothesis was that head stabilization would be impaired in children with CP. Our results indeed confirmed the starting hypothesis, since we observed significant CP vs. control differences in the head angle relative to the vertical (mainly in the frontal plane) and relative to the trunk (in the frontal and sagittal planes). These differences testify to the presence of a more marked head roll in these children, which probably enables them to develop “en bloc” compensation strategies in gait production by reducing the number of degrees of freedom that have to be controlled. In combination with a particular segmental organisation (in which the arms are thrown forward, in particular) that is not observed in healthy subjects, these strategies may compensate for the motor impairments in CP and thus produce more fluid, energy-efficient gait.

Our findings raise the issue of how the various motor coordination actions develop during the gait learning process:is the head the frame of reference used by the CP children in the learning process, given that this approach requires a high level of motor skills?

It would be useful to extend this research by performing a detailed analysis of the relationships between displacements of the centre of gravity and the trajectory of the centre of the pressure, since these are critical parameters in the achievement of balance during gait. This type of research would complement the results of the present study by observing the children’s putative strategies for stabilizing the trunk in space. Future research should examine the hypothesis whereby children CP with an “en bloc” strategy prefer to stabilize their trunk, which would probably also enable them to expend less energy when controlling the postural imbalances induced by gait. It would also be useful to extend this work by taking into account the results of the physiotherapeutic examination performed before each quantitative gait analysis, in order to establish whether or not the postural strategies developed by children with CP result from muscle weakness.

Lastly, this work may prompt clinicians to reconsider the postural organisation of children with CP during gait, with a sole objective:improvement of the child’s overall mobility by prescribing specific postural and balance exercises (the difficulty of which would vary according to the child’s abilities).

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest concerning this article.

2

Version française

2.1

Introduction

La locomotion est un processus complexe qui se caractérise par une activité rythmique, cyclique et alternée des membres inférieurs et supérieurs nécessitant pour sa mise en œuvre la mobilisation de nombreux segments corporels favorisant le déplacement du corps. Dans le cadre de la marche, cette alternance se traduit au niveau des membres inférieurs par des successions de phases de simple et de double appuis entraînant de faibles rotations de la tête et du tronc observables dans les plans sagittal et frontal . L’analyse de ces rotations met en évidence l’organisation et les stratégies motrices mises en jeu par le système nerveux central (SNC) afin de minimiser les perturbations dues aux éventuelles translations du tronc lors du déplacement .

Selon certains auteurs , le corps peut être considéré comme un système pluriarticulé exigeant une organisation particulière du SNC lors de la production d’un mouvement ou d’un déplacement. Cela pose donc le problème du contrôle impliquant la stabilisation d’un ou de plusieurs segment(s) corporel(s) représentant ainsi pour le système un référentiel stable, à partir duquel le contrôle de la posture est organisé. Le choix de ce référentiel reste donc déterminant et primordial dans la régulation posturale.

Plusieurs travaux ont montré que l’une des stratégies motrices utilisées pour l’établissement d’un cadre de référence stable dans le contrôle de l’équilibre lors de l’exécution d’un mouvement se traduit au niveau comportemental par la stabilisation de la tête dans l’espace. Elle comporte en effet trois catégories de récepteurs sensoriels, qui sont chacun sollicités notamment lors de la marche :

- •

le système visuel recueille des informations extéroceptives fournissant au sujet un référentiel stable permettant de stabiliser le champ visuel ;

- •

les capteurs vestibulaires renseignent le SNC sur les mouvements d’accélérations angulaires et linéaires de la tête dans l’espace ;

- •

les récepteurs proprioceptifs du cou (musculo-articulaires cervicales) signalent les déplacements céphaliques par rapport au tronc et à l’espace.

Cette intermodalité sensorielle permet ainsi de considérer le capteur céphalique comme un véritable référentiel de l’orientation spatiale. Cette coordination intersensorielle permet d’informer le sujet sur la position de son corps dans l’espace en fonction du contexte et de la tâche à réaliser .

Chez l’enfant, le contrôle de l’équilibre et la maîtrise de la marche autonome s’organisent au fur et à mesure de son apprentissage moteur, évoluant en fonction de l’âge et de la maturité des structures mises en jeu . La marche est donc à la fois un processus ontogénétique et le fruit d’un apprentissage généralement interprété comme le témoignage de l’intégrité physique et neurologique de l’enfant . En effet, marcher demande un certain niveau de solidité osseuse, de tonicité musculaire et de maturation du SNC. La stabilisation céphalique constitue alors pour l’enfant une habileté motrice particulière longue à maîtriser. C’est seulement vers l’âge de neuf ans que l’enfant est capable de libérer le complexe articulaire tête-tronc, lui permettant de stabiliser la tête dans l’espace pour avoir une meilleure utilisation des informations visuelles et vestibulaires au service du contrôle de l’équilibre . L’enfant développe ainsi au cours de sa croissance des stratégies d’équilibre de plus en plus complexes, passant par des phases successives de stabilisations segmentaires différentes.

Cependant, lors d’une pathologie telle que la paralysie cérébrale, les processus d’organisation de la marche et du contrôle postural présentent des altérations dont les caractéristiques dépendent de la localisation et de l’importance de l’atteinte. La paralysie cérébrale, non héréditaire, est la conséquence de lésions neurologiques centrales apparaissant sur un cerveau en pleine maturation (avant, pendant ou après la naissance jusqu’à trois ans environ). La lésion cérébrale est responsable d’anomalies dites primaires essentiellement d’atteintes motrices, se traduisant le plus souvent par un ensemble de troubles persistants du mouvement et de la posture (spasticité, anomalie du tonus musculaire, troubles de l’équilibre, etc.). De plus, diverses malformations osseuses et musculaires apparaissent au cours de la croissance (anomalies secondaires), principalement au niveau des membres inférieurs et du tronc, obligeant souvent l’enfant à adopter une attitude « fléchie » de l’ensemble du corps, ce qui complique fortement la production du pas. La marche est alors souvent caractérisée par une forte instabilité posturale et une rigidité articulaire due à une spasticité et une ataxie importantes, réduisant ainsi les degrés de libertés articulaires de l’ensemble du corps . Ces troubles empêchent donc l’expression d’une motricité harmonieuse.

À notre connaissance, la seule étude menée sur la stabilisation de la tête chez des enfants atteints de paralysie cérébrale spastique, se déplaçant sur un tapis roulant à vitesse normale, a montré que seule la variabilité de l’amplitude des déplacements de la tête différait par rapport aux enfants sains du groupe témoin .

L’objectif principal de notre étude était donc de caractériser le contrôle postural des enfants atteints de paralysie cérébrale dans la locomotion, et ainsi d’observer et de quantifier les éventuelles différences dans l’organisation et le contrôle de la stabilisation de la tête par rapport aux enfants sains. L’hypothèse qui sous-tend cette étude était que la stabilisation céphalique serait perturbée chez les enfants PC, les contraignant à développer probablement des stratégies de compensation leur permettant de réaliser la tâche demandée.

2.2

Population et méthode

2.2.1

Population

Trente-deux sujets âgés de plus de neuf ans, pouvant marcher 60 m au minimum et ne présentant aucun trouble de la compréhension et/ou de la vision ont été répartis en deux groupes mixtes :

- •

un groupe de 16 enfants atteints de paralysie cérébrale ayant pour moyenne d’âge 11 ± 1,2 ans ;

- •

un groupe de 16 enfants sains, ne présentant pas d’atteinte neurologique et/ou musculo-squelettique ayant pour moyenne d’âge 11 ± 1.5 ans.

L’étude rétrospective a été réalisée dans le cadre d’une analyse quantifiée de la marche.

2.2.2

Procédure et réalisation de l’étude

Les sujets étaient équipés de 34 marqueurs lumino-réfléchissants fixés suivant un protocole précis en différents points anatomiques, soit quatre pour la tête, cinq pour le tronc, cinq pour chaque membre supérieur, trois pour le bassin et six pour chaque membre inférieur comme décrit la référence précédente. Cette méthodologie de placement de marqueurs permet de reconstruire les axes segmentaires puis les centres articulaires mécaniques des segments les uns par rapport aux autres afin de quantifier les variables cinématiques et articulaires.

Les sujets devaient se déplacer sur un chemin de marche de 10 m de longueur et de 0,60 m de largeur délimité au sol par une couleur plus sombre. Les sujets effectuaient six aller-retours en marchant à vitesse spontanée.

2.2.3

Matériel

Afin de recueillir les données cinématiques, nous avons utilisé un système optoélectronique de capture du mouvement VICON ® (Oxford Metrics) avec huit caméras munies de sources infrarouges à une fréquence d’acquisition de 200 Hz.

2.2.4

Traitements des données

Le traitement des données du système optoélectronique a été effectué tout d’abord avec le logiciel d’acquisition Vicon-Nexus ® (Oxford Metrics) afin de réaliser la reconstruction des marqueurs dans l’espace 3D, de dater les différents événements locomoteurs notamment le repérage des contacts (pose du pied et décollage des orteils) pour chaque pied afin de définir les différents cycles de marche et de créer des fichiers c3d. À partir de là, le traitement de ces fichiers a été réalisé avec le logiciel Motion Inspector ® (Biometrics France) afin d’analyser les différents déplacements angulaires des segments de la tête et du tronc dans les trois plans de l’espace. Pour cette étude, seules les amplitudes maximales et minimales, calculées à chaque cycle de marche, des angles de la tête par rapport à l’axe orbito-meatal et l’axe horizontal ( head pitch et head roll ) et des angles de la tête par rapport au tronc illustrant ainsi les coordinations du complexe articulaire tête-tronc dans les plans sagittal et frontal ( trunk pitch et trunk roll ) ( Fig. 1 ) ont été datées et prises en compte.