Abstract

Objective

To investigate the relationships between isokinetic knee flexor and extensor muscle strength and physiological and chronological age in young soccer players.

Material and methods

Seventy-nine young, healthy, male soccer players (mean ± standard deviation age: 12.78 ± 2.88, range: 11 to 15) underwent a clinical examination (age, weight, height, body mass index and Tanner puberty stage) and an evaluation of bilateral knee flexor and extensor muscle strength on an isokinetic dynamometer. Participation in the study was voluntary.

Results

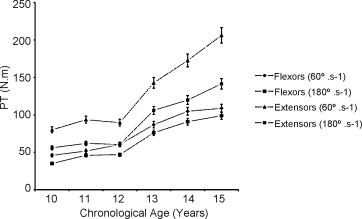

The peak torque increased progressively (by 50%) between the ages of 11 and 15 and most significantly between 12 to 14. The knee flexor/extensor ratios only decreased significantly between 14 and 15 years of age. Puberty stage was the most important determinant of the peak torque level (ahead of chronological age, weight and height) for all angular velocities ( p < 0.0001). Muscle strength increased significantly between Tanner stages 1 and 5, with the greatest increase between stages 2 and 4.

Conclusion

The present study showed that isokinetic muscle strength increases most between 12 and 13 years of age and between Tanner stages 2 and 3. There was strong correlation between muscle strength and physiological age.

Résumé

Objectif

Mesurer l’évolution de la force musculaire des fléchisseurs et extenseurs de genou chez le jeune footballeur en fonction de l’âge chronologique, de la puberté et établir une éventuelle relation.

Matériel et méthodes

Soixante-dix-neuf enfants sains âgés de 11 à 15 ans (âge moyen 12,78 ± 2,88 ans) ont effectué une évaluation clinique (âge, poids, taille, indice de masse corporelle, échelle de Tanner) et une évaluation bilatérale des muscles extenseurs et fléchisseurs du genou par dynamomètre isocinétique.

Résultats

Entre 11 et 15 ans, les valeurs de couple maximal augmentent progressivement de 50 % et de manière plus significative entre 12 à 14 ans. La valeur des ratios fléchisseurs/extenseurs du genou diminue considérablement entre 14 et 15 ans. La force musculaire augmente de façon significative entre le niveau 2 et niveau 4 de Tanner. Le stade pubertaire apparaît comme le facteur le plus déterminant du niveau de force musculaire, devant l’âge chronologique, le poids et la taille, pour toutes les vitesses angulaires ( p < 0,0001).

Conclusion

Cette étude montre une augmentation importante de la force musculaire entre 12 et 13 ans, et entre le deuxième et le troisième stade de la classification de Tanner. Il existe une corrélation significative entre la force musculaire et l’âge pubertaire.

1

English version

1.1

Introduction

Puberty is an important period of transition from childhood to adulthood that is often viewed within the context of sexual maturation and growth in stature. The complex underlying biological events include changes in the nervous and endocrine systems and the corresponding anthropometric and physiological changes . During and after puberty, a marked increase in physical performance occurs as a result of muscular, neuronal, hormonal and biomechanical factors . The development of muscle strength in children is related to factors such as age, body size and sexual maturation . The strength that a muscle can develop is, in turn, generally proportional to its cross-sectional area and the level of intramuscular coordination.

Muscle strength is generally expressed as torque, which is the product of the force that a muscle exerts and its lever-arm length (i.e. the perpendicular distance from the line of action of the force to the joint’s centre of rotation). Muscle strength can be evaluated in isometric, isotonic or isokinetic modes. Dynamic modes (such as the isokinetic paradigm) have been preferred in most works over the last 30 years.

The development of muscle strength in children is related to the relationship between torque output and the angular velocity of joint movement. The few published studies on the torque/velocity relationship in children indicate a similar, adult-like pattern for preadolescent girls and for prepubertal boys and girls . However, in paediatric studies, the roles of age and puberty in the development of isokinetic strength are less well understood. Some studies have indicated that isokinetic strength increases with chronological age , particularly between the ages of 10 to 15. In fact, there are very few studies on the mechanisms behind this muscle strength increase. Furthermore, little is known about the relationships between the strength increase and factors such as physiological age, which is probably an important explanatory factor in the high observed variability of the development in stature, morphology, strength and physical abilities . Only one study (by Kellis et al. ) has reported correlations between muscle strength, chronological age and certain morphological characteristics (height, weight and body mass index [BMI]).

Moreover, it has been reported that high-intensity physical activity can modify the development of puberty . However, we are not aware of any studies on the change in dynamic, isokinetic muscle strength as a function of physiological age and the intensity of sports activity in preadolescent children.

Hence, we sought to determine the development of muscle strength in preadolescent children, in order to establish the most appropriate type of strength training during sporting activity (soccer, in this case) in this population. Moreover, we believe that it is important to be able to predict and prevent the joint damage often associated with a lack of muscle strength during bone growth.

Hence, we decided to analyse the relationship between muscle strength, morphological characteristics and chronological and physiological age in a population of preadolescent, male soccer players aged from 11 to 15 years (i.e. the usual age range for the development of puberty).

1.2

Subjects and methods

1.2.1

Subjects

We included 79 boys (mean ± standard deviation [S.D.] age: 12.78 ± 2.88, range: 11 to 15) attending a special soccer training school in the study. All the subjects had passed a medical examination at most 10 days before the muscle strength tests and none were suffering from any medical diseases or trauma-related disorders at the time of the study.

All the children included in the study played soccer for 6 hours per week and had been playing intensively for between 1 and 3 years. The study population comprised a variety of field positions. The group was homogeneous since none of the children had a history of lower limb injuries.

The study protocol was approved by the local independent ethics committee. Both the subjects and their parents gave their written, informed consent prior to participation in the study.

1.2.2

Isokinetic strength analysis

Measurements of the isokinetic strength of the knee flexor and extensor muscles were made on an isokinetic dynamometer (Cybex 6000 ® ). The device’s back support was inclined at 15° to the vertical and the seated subject was secured with belts at the waist and shoulder levels. The knee was aligned with the dynamometer’s lever-arm and the ankle was secured to the latter’s distal section. For each limb, concentric-mode isokinetic tests were performed at an angular velocity of 60°/s and then 180°/s. Subjects were asked to repeat four flexion–extension movements and were given verbal encouragement during the test. The dominant limb was tested first. Subjects warmed up by performing 20 submaximal concentric contractions (i.e. between 20 and 80% of the estimated maximum effort) of the corresponding muscles at slow angular velocities (15°/s). Prior to each test series, the subjects also performed two or three submaximal practice repetitions. Subjects were always allowed to rest for 120 seconds between each series.

The protocol was adapted (in terms of the angular velocity and the number of repetitions) to suit the younger subjects. Angular speeds generally considered to be slow (60°/s) or medium (180°/s) were better tolerated and more reproducible. Furthermore, the number of repetitions did not exceed 5.

It is important to remember that isokinetic muscle measurements have good reliability, namely a good correlation ( r ranging from 0.91 to 0.98) between the isometric, isotonic and isokinetic forces measured in the same subject.

1.2.3

Clinical parameters

Each subject’s age, weight, height, BMI and the Tanner puberty stage were recorded during a clinical examination. All examinations were performed by the same paediatrician. Likewise, physiological maturity (as assessed by the Tanner puberty stage) was also scored by the same paediatrician. The maturation data for the study population were similar to reference values (with Tanner’s five stages S1–S5 corresponding to Sempé’s nine bone age levels P1–P9) .

The clinical examination enabled us to exclude children with cardiovascular disease, muscle disorders and specific contraindications for the use of an isokinetic dynamometer.

1.2.4

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics (mean ± S.D.) for chronological age, weight, height and BMI were calculated. An analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare isokinetic strength parameters as a function of chronological age and physiological age.

The “correlation Z-test” was used to determine correlations between morphological parameters, physiological maturity and isokinetic strength parameters. A Z-test can be used to test the mean of a population against a reference value or to compare the means of two populations with large samples ( n ≥ 30), regardless of whether or not the population’s S.D. is known. The test can also used for testing the frequency of a given characteristic versus a reference value or to compare the frequencies in two populations.

The significance threshold was set at p < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed with Statview ® software.

1.3

Results

Table 1 presents the population’s characteristics according to chronological age and physiological maturity.

| Chronological age (years) | Puberty stage | Weight (kg) | Height (cm) | BMI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11 ( n = 8) | S1: 12.5% | 34.24 ± 5.07 | 142.88 ± 5.79 | 16.79 ± 2.63 |

| S2: 87.5% | ||||

| p values | NS | NS | NS | |

| 12 ( n = 5) | S2: 80% | 37.30 ± 6.98 | 147 ± 8.25 | 17.13 ± 1.64 |

| S3: 20% | ||||

| p values | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | |

| 13 ( n = 29) | S1: 28% | 50.46 ± 9.61 | 162.05 ± 9.10 | 19.05 ± 2.06 |

| S2: 17% | ||||

| S3: 31% | ||||

| S4: 17% | ||||

| S5: 7% | ||||

| p values | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | |

| 14 ( n = 21) | S1: 6% | 59.46 ± 7.70 | 171.17 ± 6.85 | 20.19 ± 1.44 |

| S2: 19% | ||||

| S3: 33% | ||||

| S4: 33% | ||||

| S5: 9% | ||||

| p values | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | < 0.05 | |

| 15 ( n = 16) | S4: 63% | 63.83 ± 5.64 | 173.75 ± 5.29 | 21.11 ± 0.99 |

| S5: 37% | ||||

| Total ( n = 79) | 52.97 ± 12.18 | 163.81 ± 12.19 | 19.43 ± 2.20 | |

1.3.1

Correlation between morphological parameters, chronological age and isokinetic muscle strength

Given the lack of a statistically significant difference between the dominant and non-dominant legs, we pooled the results from each side ( Table 2 ).

| Variable | Extensor strength | Flexor strength | Flexor/extensor ratio | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 60°/s | 180°/s | 60°/s | 180°/s | 60°/s | 180°/s | |

| Age | 0.71 | 0.67 | 0.61 | 0.62 | −0.13 | −0.05 |

| Weight | 0.88 | 0.85 | 0.86 | 0.83 | −0.23 | 0.01 |

| Height | 0.80 | 0.78 | 0.80 | 0.79 | −0.05 | 0.05 |

| BMI | 0.79 | 0.76 | 0.77 | 0.73 | −0.03 | −0.02 |

According to the results of a Z-test, there was a significant correlation between isokinetic strength on one hand, and chronological age and morphological parameters on the other ( p < 0.05).

Between the ages of 11 and 12, the changes in muscle strength were small (from 0% to 13% for flexors and from 5% to 10% for extensors). This was also the case when comparing strength at 14 and 15. In contrast, the muscle strength differences between the ages of 12 and 13 were around 30% for flexors and 40% for extensors. The differences between the ages of 13 and 14 were around 15%. Between the ages of 14 and 15, the change in extensor muscle strength (20%) differed markedly from the change in flexor strength (below 10%).

1.3.2

The development of isokinetic strength as a function of puberty stage:

There was a large, statistically significant difference when comparing S1 and S5 (around 40% for knee flexors and 50% for knee extensors; Table 3 , Fig. 1 ). The difference between successive stages was greatest when comparing S2 and S3 (around 30%). The difference was still significant for S3 and S4 (15% for flexors and 20% for extensors) but not for S4 and S5 (there was even a 7% reduction for flexors at 180°/s).

| Muscles and angular speed | S1 | p | S2 | p | S3 | p | S4 | p | S5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knee extensors, 60°/s | 115.3 ± 24.7 | NS | 114.7 ± 33.2 | < 0.05 | 156.9 ± 31.6 | < 0.05 | 193.7 ± 41.7 | < 0.05 | 212.7 ± 38.9 |

| Knee flexors, 60°/s | 69.8 ± 18.8 | NS | 68.5 ± 20.2 | < 0.05 | 97.5 ± 21.5 | < 0.05 | 115.7 ± 24.5 | NS | 119.7 ± 28.1 |

| Extensor/flexor ratio, 60°/s | 0.61 ± 0.10 | NS | 0.61 ± 0.11 | NS | 0.63 ± 0.11 | NS | 0.62 ± 0.20 | NS | 0.57 ± 0.11 |

| Knee extensors, 180°/s | 74.2 ± 13.3 | NS | 78.9 ± 24.2 | < 0.05 | 110.5 ± 23.8 | < 0.05 | 137.4 ± 30.9 | NS | 143.4 ± 25.6 |

| Knee flexors, 180°/s | 59.0 ± 19.3 | NS | 59.9 ± 19.4 | < 0.05 | 87.9 ± 22.2 | < 0.05 | 101.1 ± 22.5 | NS | 97.8 ± 25.6 |

| Extensor/flexor ratio, 180°/s | 0.79 ± 0.18 | NS | 0.77 ± 0.13 | NS | 0.81 ± 0.19 | NS | 0.75 ± 0.16 | NS | 0.68 ± 0.14 |

We found the same statistically significant results after adjusting the strength values for the subjects’ weight and BMI.

1.4

Discussion

Although several descriptive studies have characterized isokinetic muscle strength in children, few have spanned childhood and puberty and hardly any have adopted a longitudinal approach . The present cross-sectional study provided valuable information on knee flexor and extensor muscle strength in preadolescent male soccer players as a function of chronological and physiological age.

The number of subjects in our study was relatively high (in comparison with similar studies in the literature) and the study population was relatively homogeneous.

1.4.1

The development of strength as a function of chronological age and certain morphological criteria

The strong observed correlations between isokinetic muscle strength on one hand, and chronological age and anthropometric characteristics (such as height and weight) on the other agree with the literature data ( Fig. 2 ). Our results show that bodyweight is the variable which correlates most strongly with the various peak torque values, as reported by Gross et al. in 134 healthy volunteers aged between 10 and 80. Our results also agree with those reported by Kellis et al. , who found an even more strongly significant relationship for concentric and eccentric isokinetic strength for both knee extensors and flexors. Between 73% and 93% of the variance were explained by combinations of age, body mass, percentage of body fat and hours spent training per week.

Our results evidenced an increase in strength between the ages of 11 and 15, with a particularly sharp increase between 12 and 14. In absolute terms, the peak torque/weight values double between the ages of 11 and 15 years. These findings are in agreement with a large body of literature data . Gobelet found the same change in bodyweight-adjusted peak torque between 12 years and 14 years in 21 untrained subjects. The strength increase corresponded to an achievement of Tanner stages 4 or 5 for a large majority of the subjects.

Our data on knee flexor/extensor strength ratios at the age of 15 years are similar to those obtained by Gobelet . However, in our study, there was no difference with chronological age. Gobelet noted a decrease in the knee flexor/extensor ratio from 70% to 53% between the ages of 10 and 15 years with isokinetic testing at 30°/s with a population of 63 subjects aged from 5 to 25. The authors suggested that over time, hamstrings acquire histological and physiological characteristics that prevent the generation of slow movements.

1.4.2

The development of muscle strength as a function of puberty stage

To the best of our knowledge, there are no published data on the relationship between isokinetic muscle strength and physiological maturity in preadolescents (the Tanner puberty stage). Our results confirm the hypothesis whereby certain periods of growth have a major impact on muscle strength. It is noteworthy that our study population was more evenly distributed in terms of Tanner stage than chronological age; this is probably because the Tanner classification corresponds to a more progressive growth change than chronological age. However, our results are not comparable with literature data in other respects. We did not observe the pattern of knee flexor and extensor strength changes after the age of 14 reported by other researchers ; this difference may be due to a specific adaptation to soccer training in our population.

We believe that the present study provides useful data on muscle strength differences between maturity levels (as defined by the Tanner puberty stage). Understandably, our study was subject to a number of limitations. Firstly, this was a cross-sectional study rather than a prospective study. Nevertheless, the levels of physical maturity were probably homogeneous in our study population; all the subjects were male, had normal-for-age BMI values and were performing high-level soccer (which conditioned physical capacity and also required certain morphological capacities). However, the lack of a control group (i.e. constituted by participants no performing regular, intensive, specific sporting activity) must be taking into account when considering our results. Secondly, our statistical analysis with respect to chronological age included one rather small subgroup ( n = 5 for 12 years age). Thirdly, we observed large inter-individual variations in muscle strength, despite the homogeneity of characteristics such as gender and training level.

It would be interesting to couple muscle strength evaluation with endocrinology data (hormonal rate of testosterone in particular) in a prospective study. It is now accepted that preadolescents’ morphological parameters change proportionately with the different puberty stages.

1.5

Conclusion

This cross-sectional study of 79 male, preadolescent soccer players described the relationship between knee flexor/extensor muscle strength and chronological and physiological age. We observed the sharpest increase in muscle strength between Tanner puberty stages 2 and 3. There was strong correlation between knee muscle strength and morphological characteristics. The classification of juvenile subjects in terms of maturity level seems to fit more closely with physiological growth processes, particularly during puberty.

2

Version française

2.1

Introduction

La puberté est une période importante de transition de l’enfance à l’âge adulte qui est souvent perçue à travers le contexte de la maturation sexuelle et de la croissance morphologique. Les événements biologiques complexes sous-jacents incluent les changements dans le système nerveux et le système endocrinien ainsi que pour les paramètres anthropométriques et physiologiques . Pendant et après la puberté, une augmentation marquée des performances physiques se produit à la suite de développements de l’activité musculaire, neuronale, hormonale ainsi que des facteurs biomécaniques . Le développement de la force musculaire chez les enfants est lié à des facteurs comme l’âge, la taille corporelle et la maturation sexuelle . La force qu’un muscle peut développer semble généralement proportionnelle à sa section transversale et au niveau de la coordination intramusculaire.

La force musculaire est généralement exprimée en couple, qui est le produit de la force exercée par un muscle et son levier de lien de dépendance (soit la distance perpendiculaire de la ligne d’action de la force au centre de l’articulation de rotation). La force musculaire peut être évaluée en mode isométrique, isotonique ou isocinétique. Les modes dynamiques (comme l’isocinétisme) ont été privilégiés dans la plupart des travaux au cours des 30 dernières années.

Le développement de la force musculaire chez les enfants est lié à la relation entre la production de couple et la vitesse angulaire du mouvement de l’articulation. Les quelques études publiées sur la relation force/vitesse chez les enfants indiquent une évolution comparable chez les adultes comme modèle pour les filles préadolescentes et chez les garçons et les filles prépubères . Toutefois, dans les études pédiatriques, les rôles de l’âge et la puberté dans le développement de la force isocinétique sont moins bien compris. Certaines études ont montré des augmentations de la force isocinétique avec l’âge chronologique , en particulier entre 10 à 15 ans. En fait, il y a très peu d’études sur les mécanismes responsables de cette augmentation de force musculaire. En outre, on ne retrouve que peu de travaux sur les relations entre l’augmentation de la force et des facteurs tels que l’âge physiologique, qui est probablement un facteur explicatif important dans la variabilité élevée observée de l’évolution de la stature, la morphologie, la force et les capacités physiques . Une seule étude (réalisée par Kellis et al. ) a rapporté des corrélations entre la force musculaire, l’âge chronologique et de certaines caractéristiques morphologiques (taille, poids et l’indice de masse corporelle [IMC]).

En outre, il a été retrouvé qu’une activité physique très intense pouvait modifier le développement de la puberté . Cependant, nous ne savons pas des modifications de la force musculaire isocinétique en fonction de l’âge physiologique et de l’intensité de l’activité sportive chez ces enfants préadolescents.

Donc, nous avons cherché à déterminer l’évolution de la force musculaire chez les enfants préadolescents, afin d’établir le type d’entraînement le plus approprié afin d’améliorer la force musculaire au cours d’activités physiques (à l’activité football, dans ce cas) dans cette population. En outre, nous pensons qu’il est important d’être capable de prédire et de prévenir les lésions articulaires souvent associées à un manque de force musculaire durant la croissance osseuse.

Par conséquent, nous avons décidé de mesurer l’évolution de la force musculaire des fléchisseurs et extenseurs de genou chez le jeune footballeur en fonction de l’âge chronologique, de la puberté et d’en établir une éventuelle relation.

2.2

Sujets et méthodes

2.2.1

Population

Nous avons inclus 79 garçons (d’âge moyen : 12,78 ± 2,88 ans, 11 à 15 ans), tous en centre de formation de football. Tous les sujets ont subi un examen médical au plus dix jours avant les tests de force musculaires et aucun antécédent de traumatisme ni de maladie n’était détecté. Tous les enfants inclus dans l’étude pratiquaient le football à raison de six heures par semaine et jouaient de façon intensive dans une période de un à trois ans. La population d’étude comprenait une variété de postes sur le terrain. Le groupe est homogène, puisque aucun des enfants n’avait des antécédents de lésions des membres inférieurs. Le protocole d’étude a été approuvé par le comité d’éthique local indépendant. Les sujets et leurs parents ont donné leur consentement éclairé par écrit avant la participation à l’étude.

2.2.2

Mesures de force musculaire

Les mesures de la force isocinétique des extenseurs/fléchisseurs du genou ont été effectués sur un dynamomètre isocinétique (Cybex 6000 ® , Lumex Inc, NY, États-Unis). Le dispositif de support pour le dos était incliné à 15° à la verticale et le sujet assis était sanglé avec des ceintures à la taille et le niveau de l’épaule. L’articulation du genou était alignée avec l’axe de rotation du bras de levier et la cheville était sanglée par la partie distale de ce dernier. Pour chaque jambe, des tests en mode concentrique ont été effectués à une vitesse angulaire de 60°/s, puis 180°/s. Les sujets ont été invités à répéter quatre mouvements de flexion–extension et ont reçu des encouragements verbaux lors des mouvements. La jambe dominante a été testée en premier. Tous les sujets ont été échauffés en réalisant 20 contractions en mode concentriques en sous maximal (c’est-à-dire entre 20 et 80 % de l’effort maximal estimé) à des vitesses angulaire lentes (15°/s). Avant chaque série, les sujets ont également effectué deux ou trois répétitions sous-maximales. Les sujets étaient autorisés à se reposer pendant 120 secondes entre chaque série.

Le protocole a été adapté (en termes de vitesse angulaire et du nombre de répétitions) en fonction des sujets plus jeunes. Les vitesses angulaires généralement considérée comme lente (de 60°/s) ou intermédiaires (180°/s) sont mieux tolérées et plus reproductibles. En outre, le nombre de répétitions ne dépasse pas 5. Il semble important de se rappeler que les mesures de force musculaire isocinétique ont une bonne fiabilité, à savoir une bonne corrélation ( r variant de 0,91 à 0,98) entre les modes isométriques, isotoniques et isocinétiques mesurée pour un même sujet.

2.2.3

Les paramètres cliniques

Pour chaque sujet, l’âge, le poids, la taille, l’IMC et le score de puberté de Tanner ont été enregistrés lors d’un examen clinique. Tous les examens ont été effectués par le même pédiatre. De même, la maturité physiologique (évaluée par l’échelle de puberté de Tanner) a été également évaluée par le même pédiatre. Les données de maturation de la population étudiée étaient similaires aux valeurs de référence (avec cinq stades de Tanner S1–S5 correspondant à neuf ans de Sempé P1 niveaux os–P9) . L’examen clinique nous a permis d’exclure les enfants atteints de maladies cardiovasculaires, des troubles musculaires et ainsi toutes contre-indications spécifiques pour l’utilisation d’un dynamomètre isocinétique.

2.2.4

L’analyse statistique

Des statistiques descriptives (moyenne ± écart-type) pour l’âge chronologique, le poids, la taille et l’IMC ont été calculés. Une analyse de variance (Anova) a été utilisé pour comparer les paramètres de force musculaire isocinétique en fonction de l’âge chronologique et l’âge physiologique. Le « test Z de corrélation » a été utilisé pour déterminer les corrélations entre les paramètres morphologiques, la maturité physiologique et paramètres de force musculaire isocinétique. Un Z-test peut être utilisé pour tester la moyenne d’une population contre une valeur de référence ou de comparer des moyennes de deux populations avec des échantillons de grande taille ( n ≥ 30), indépendamment de savoir si ou non l’écart type de la population est connue. Le test peut également être utilisé pour tester la fréquence de données par rapport à une valeur de référence ou de comparer les fréquences dans deux populations.

Le seuil de signification a été fixé à p < 0,05. Toutes les analyses statistiques ont été effectuées avec le logiciel Statview ® .

2.3

Résultats

Le Tableau 1 présente les caractéristiques de la population selon l’âge chronologique et la maturité physiologique.