Introduction

The regional musculoskeletal examination (RMSE) of the neck is designed to build on the sequences and techniques taught in the SMSE and GMSE. It is intended to provide a comprehensive assessment of structure and function combined with special testing to permit you to evaluate common, important musculoskeletal problems of the neck seen in an ambulatory setting. The skills involved require practice and careful attention to technique. However, they can be learned and mastered on normal individuals.

Clinical Utility

The RMSE of the neck is clinically useful as the initial examination in individuals whose history clearly suggests an acute or chronic neck problem: neck-predominant spinal pain or upper extremity–predominant pain (possible cervical nerve root irritation). With practice, a systematic, efficient RMSE of the neck can be performed in ∼3 to 4 minutes.

Furthermore, the RMSE of the neck provides the foundation for learning additional, more refined diagnostic techniques through your later exposure to orthopedic surgeons, rheumatologists, physiatrists, physical therapists, and others specifically involved in the diagnosis and treatment of neck problems.

Objectives

This instructional program will enable you to identify important anatomical features, functional relationships, and common pathologic conditions involving the neck. Essential content includes

- Structural and functional anatomy

- Cervical spine range of motion

- (Myofascial) trigger points and (fibromyalgia) tender points

- Suspected nerve root irritation

- Suspected cervical myelopathy

Essential Concepts

The cervical spine consists of seven vertebrae, increasing progressively in size from C1 to C7.

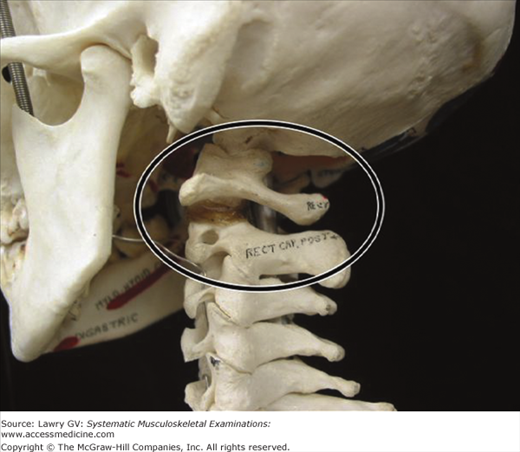

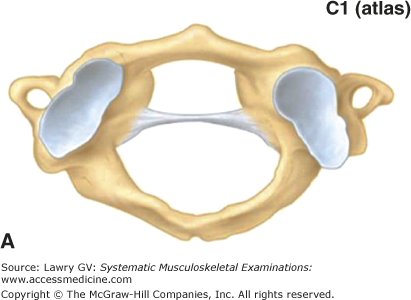

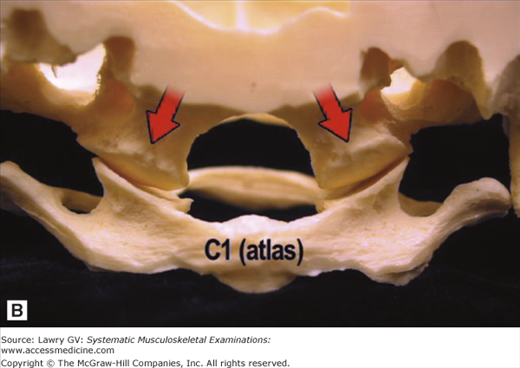

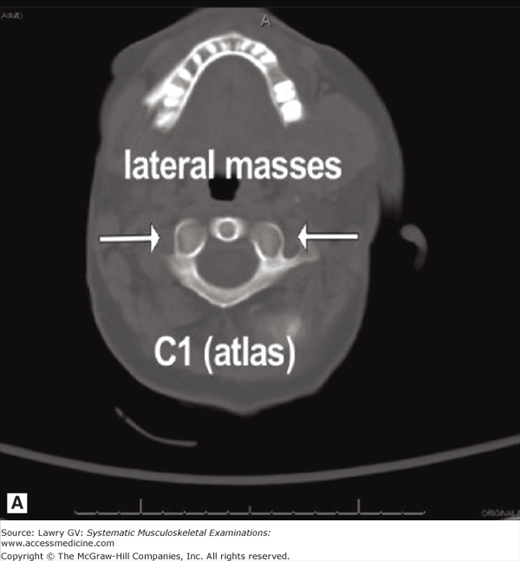

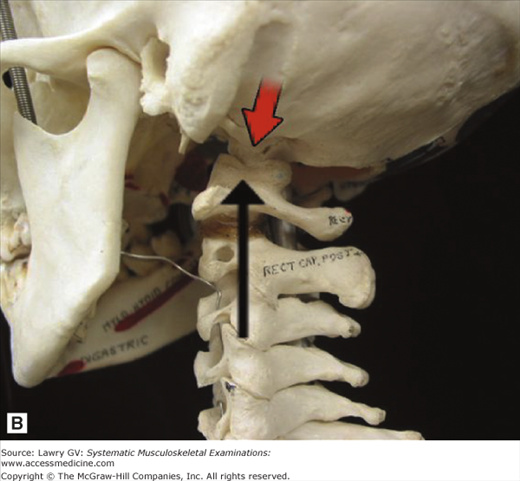

C1 and C2 deserve special comment because they have unique features (Fig. 6–1). C1 (atlas) lacks a vertebral body but consists of anterior and posterior arches and two cup-shaped lateral masses (Fig. 6–2A). Just as in Greek mythology, Atlas was forced to bear the weight of the world on his shoulders, so the cervical atlas (C1) bears the skull on its “shoulders” (lateral masses; Fig. 6–2B), each articulating with the occipital condyles on either side of the foramen magnum at the atlantooccipital joints (Fig. 6–3A, B). These joints make small contributions to flexion and extension (nodding) and lateral flexion.

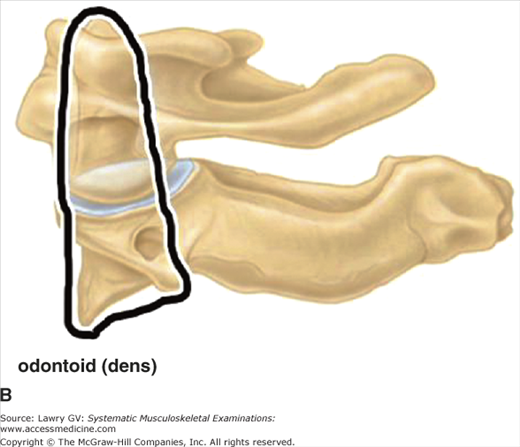

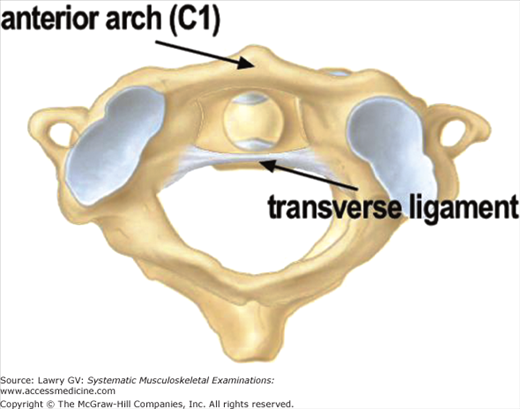

C2 (axis) has a vertebral body anteriorly and from it a fingerlike peg projects superiorly (Fig. 6–4A, B). This bony process called the odontoid or dens (dont and dens from Latin for tooth) sits snuggly against the anterior arch of the atlas. The two are held together by the fibrous transverse ligament, which runs behind the odontoid process (Fig. 6–5). About 50° of rotation of the cervical spine occurs at the atlantoaxial joint (C1-C2).

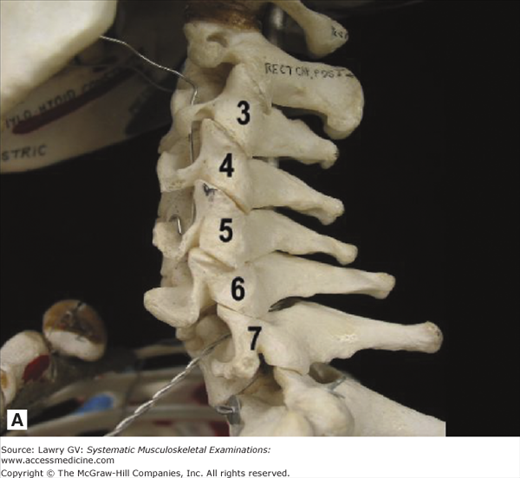

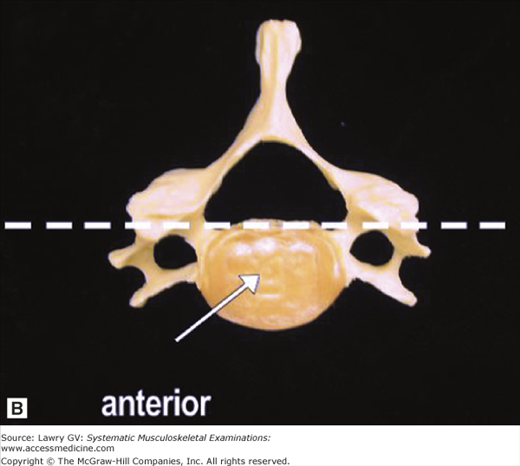

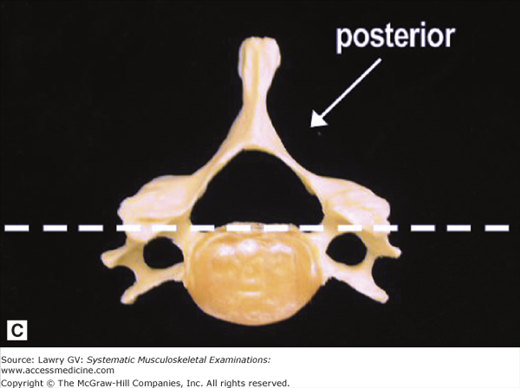

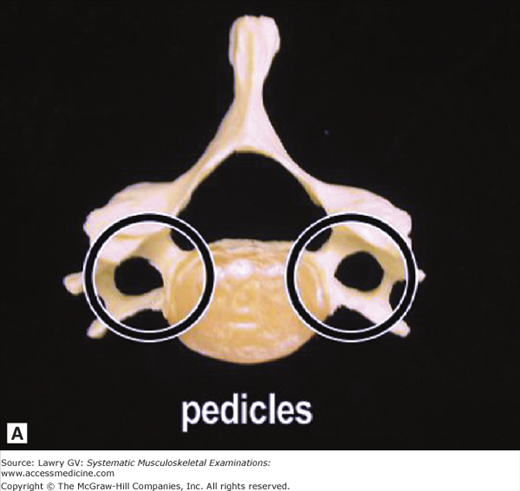

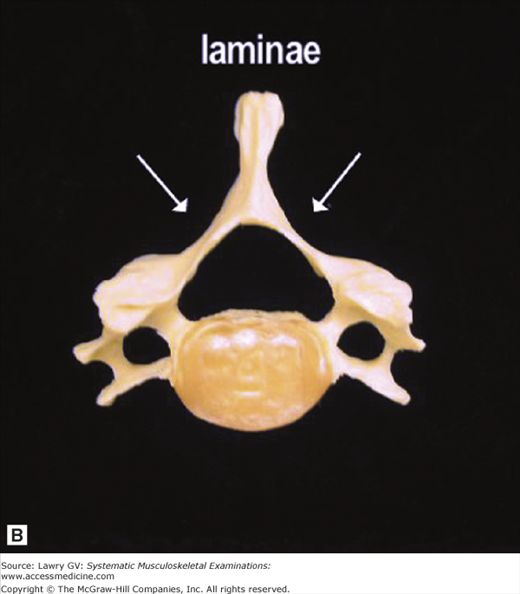

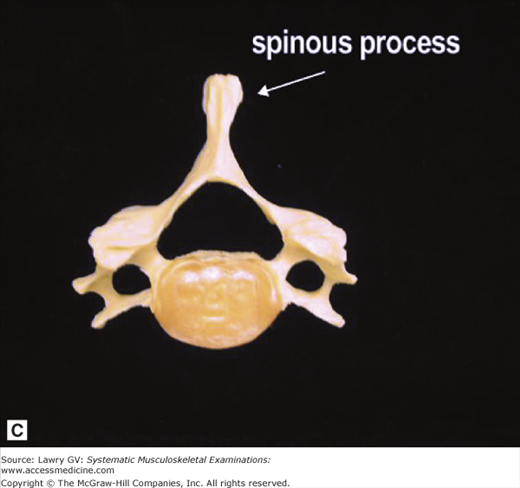

C3 through C7 are more typical vertebrae and possess an anterior weight-bearing element, the vertebral body, and posterior elements, including the neural arch and facet joints (Fig. 6–6A through C). The neural arch is made up of two pedicles attached to the vertebral body and two laminae which fuse in the midline to form the spinous process (Fig. 6–7A through C).

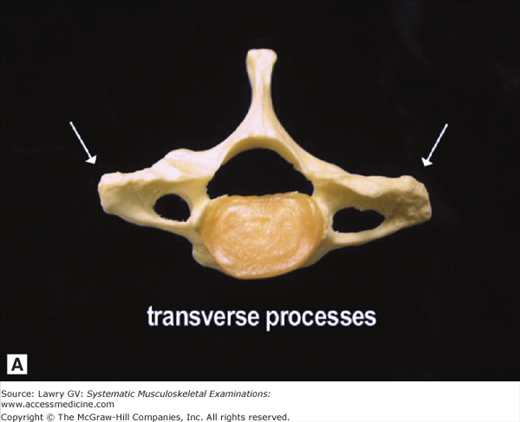

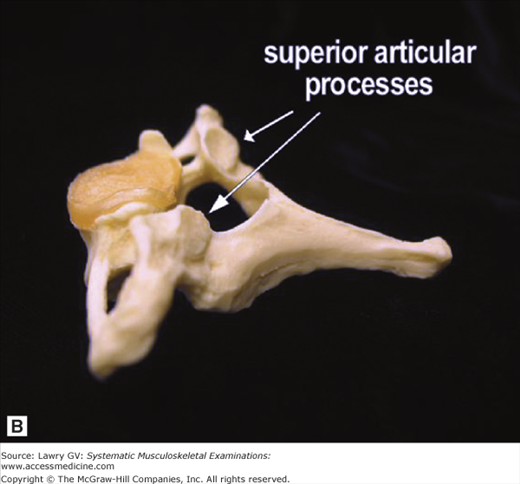

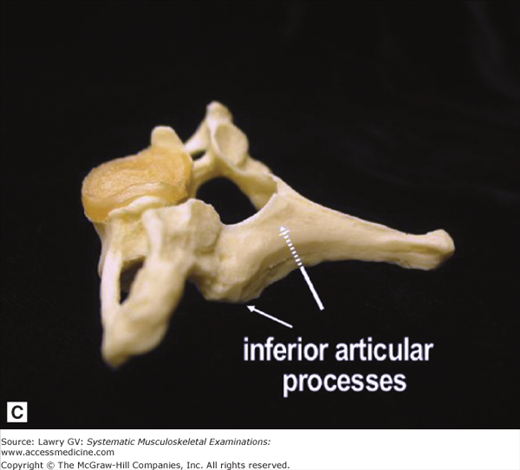

Three pairs of bony processes project from each arch close to the junction of the pedicles and laminae: two transverse processes, two superior articular processes, and two inferior articular processes (Fig. 6–8A through C).

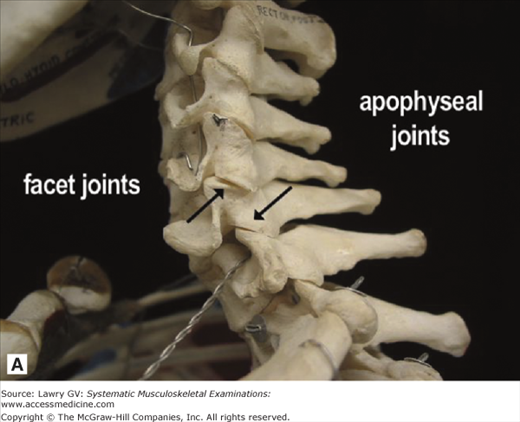

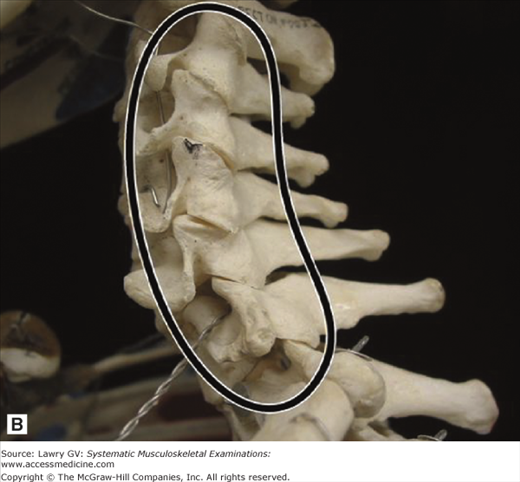

Together, the superior and inferior articular processes form the facet (apophyseal) joints. These “stacking joints” allow movements at the spine and prevent forward sliding of one vertebra on another (Fig. 6–9A, B).

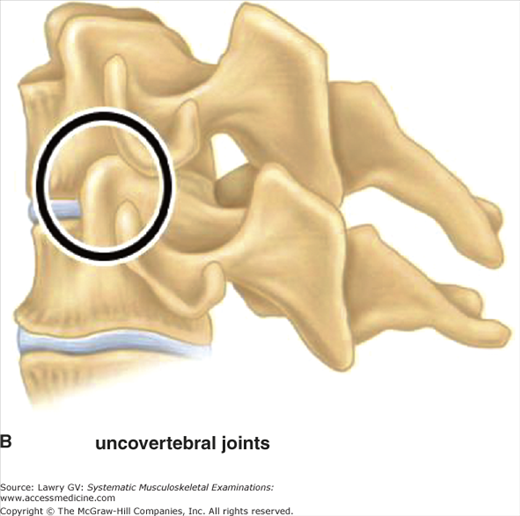

In addition, C3 through C7 frequently have unique bony projections posteriorly and laterally from the superior end plate of each vertebra which articulate with the beveled inferolateral surface of the vertebra above to form the uncovertebral joints of Luschka (Fig. 6–10A, B). These joints permit greater movements at the cervical spine compared with the thoracic and lumbar spine, and also provide lateral stability to the diskovertebral complex, forming a barrier to extrusion of disk material posterolaterally.

The C3 through C7 vertebrae allow cervical spinal flexion, extension, lateral bending, and rotation. In the resting neutral position, the posterior process of C7 (vertebra prominens) is palpable in the midline at the base of the neck.

The patient’s history is the essential first step in all musculoskeletal diagnosis and directs the focus of an appropriate physical examination. Particularly useful background information includes age; occupation and recreational activities; a history of injury or arthritis; and any prior neck problems.

An initial pain assessment can be well delineated with the use of the mnemonic OPQRSTU: where O = Onset; P = Precipitating and ameliorating factors; Q = Quality; R = Radiation; S = Severity; T = Timing; and U = Urinary or upper motor neuron symptoms.

Once pain characteristics are established, additional historical features may help focus the diagnostic evaluation.

Is there evidence of major trauma or injury?

Is there evidence of neurologic compromise requiring surgical consultation?

Is there an underlying serious systemic disease?

Is there social or psychological distress that may amplify, prolong, or complicate the pain?

Most neck pain is attributed to muscle and/or ligamentous strain, facet joint arthritis, intervertebral disk herniation, or other miscellaneous causes. However, despite advances in imaging and neurodiagnosis, the etiology of most acute and chronic neck pain is complex and frequently poorly understood.

The thrust of a brief, focused history should inquire about risk factors pointing to fracture, malignancy, infection, underlying visceral or systemic disease, or the need for urgent surgical consultation. The musculoskeletal physical examination of the neck should be focused and used to confirm or refute diagnostic hypotheses generated by a focused, but thoughtful history.

Acute uncomplicated idiopathic neck and low back pain accounts for the vast majority of spinal pain seen in clinical practice. A focused clinical history and physical examination is important, and in the absence of serious underlying conditions, a diagnosis of acute nonspecific neck or low back pain can be made.

A definitive anatomic diagnosis cannot be made in as many as 85% of patients presenting with acute neck or low back pain, but up to two-thirds of such patients have resolution of their symptoms in 4 to 8 weeks.

Fortified by this information, the clinician is able to direct subsequent management efforts at reassurance and resumption of normal functional activity rather than extensive and expensive (and frequently misleading) imaging studies.

The Examination, Overview

Observe the patient’s posture, movement, and behaviors throughout the history and the physical examination.

With the patient seated, observe the resting posture and alignment of the cervical spine. Note any resting asymmetry or deformity and inspect for the normal resting cervical lordosis. Next, inspect the skin. Note any scars or rashes.

Palpate the inion (greater occipital protuberance), then palpate inferiorly along the spinous processes from C2 to the mid-thoracic spine and note any tenderness. Assess for tender points or trigger points by palpating the suboccipital muscle insertions, the mid to upper trapezius, the supraspinatus, and medial scapular borders on each side.

Assess neck flexion by asking the patient to touch the chin to the chest. Assess neck extension by asking the patient to look up at the ceiling. Observe right and left rotation by asking the patient to place the chin on each shoulder. Assess lateral flexion (or lateral bending) by asking the patient to incline the ear toward each shoulder.

If indicated from the history or physical, perform special testing for possible nerve root irritation or signs of cervical myelopathy.

Assess biceps, brachioradialis, and triceps reflexes. Test muscle strength of deltoids (resisted shoulder abduction), biceps (resisted elbow flexion), triceps (resisted elbow extension), and interossei (spreading fingers against resistance). Now, assess sensation to light touch and/or pin prick over the lateral deltoid, thumb and index finger, middle finger, and ring and little fingers.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree