Introduction

The regional musculoskeletal examination (RMSE) of the low back is designed to build on the sequences and techniques taught in the SMSE and GMSE. It is intended to provide a comprehensive assessment of structure and function combined with special testing to permit you to evaluate common important musculoskeletal problems of the low back seen in an ambulatory setting. The skills involved require practice and careful attention to technique. However, they can be learned and mastered on normal individuals.

Clinical Utility

The RMSE of the low back is clinically useful as the initial examination in individuals whose history clearly suggests an acute or chronic low back problem: back-predominant spinal pain or lower extremity–predominant pain (possible lumbosacral nerve root irritation) or associated systemic or visceral disease. With practice, a systematic, efficient RMSE of the low back can be performed in ∼4 to 5 minutes.

Furthermore, the RMSE of the low back provides the foundation for learning additional, more refined diagnostic techniques through your later exposure to orthopedic surgeons, rheumatologists, physiatrists, physical therapists, and others specifically involved in the diagnosis and treatment of back problems.

Objectives

This instructional program will enable you to identify essential anatomical features, functional relationships, and common pathologic conditions involving the low back. Essential content includes

- Observation of posture, gait, and movement

- Inspection, palpation, and range of motion of the lumbosacral spine

- Examination of the hip

- Evaluation for possible nerve root irritation

- Evaluation for important signs of psychological distress

- Evaluation for sacroiliitis/spondylarthritis

- Consideration of systemic or visceral disease.

Essential Concepts

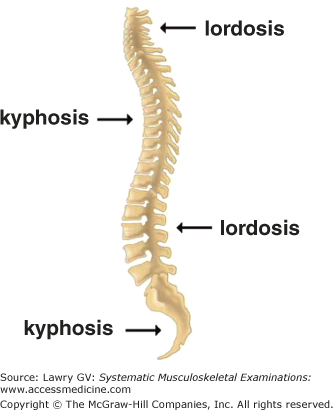

The spinal column is composed of four balanced curves: the cervical lordosis, thoracic kyphosis, lumbar lordosis, and coccygeal kyphosis (Fig. 7–1). The compensatory nature of these balanced curves allows the normal resting erect posture to be maintained with minimal muscular effort.

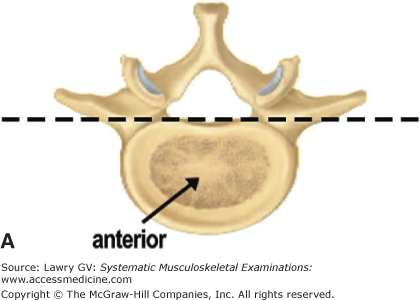

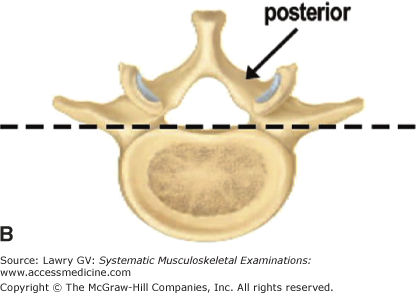

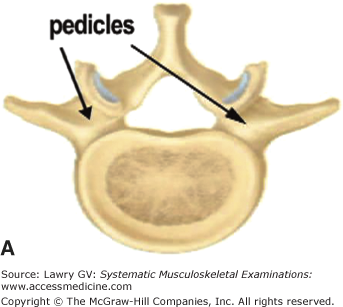

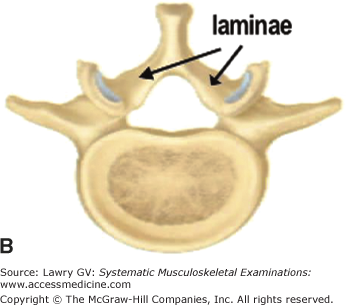

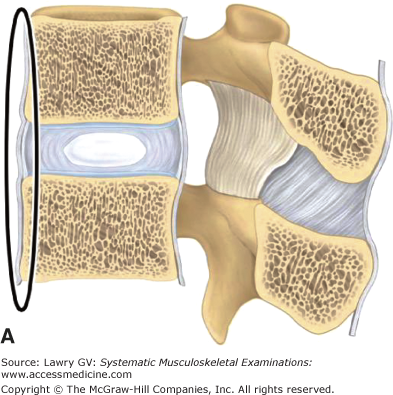

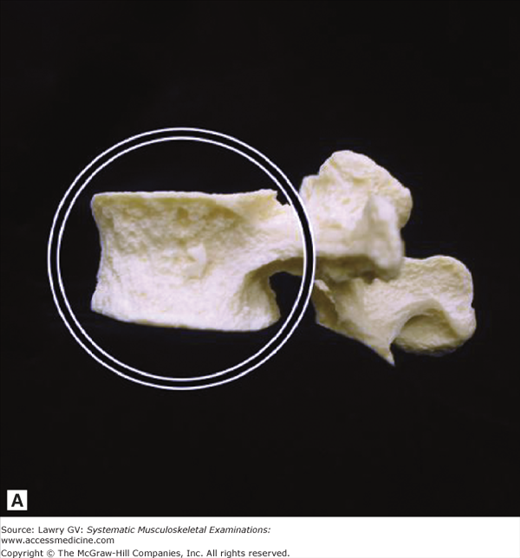

The vertebrae have important common features: an anterior element, the weight-bearing vertebral body; and posterior elements, the neural arch and facet joints (Fig. 7–2A, B).

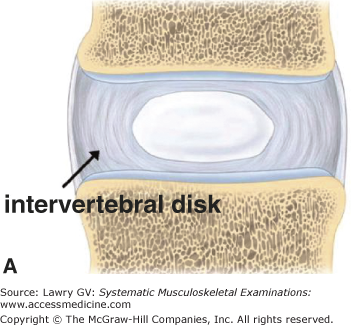

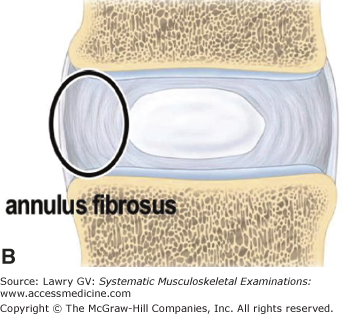

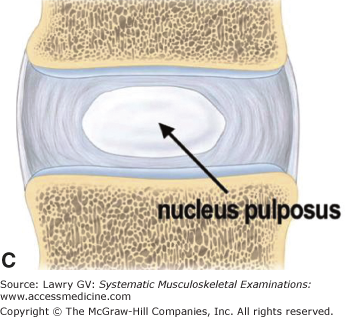

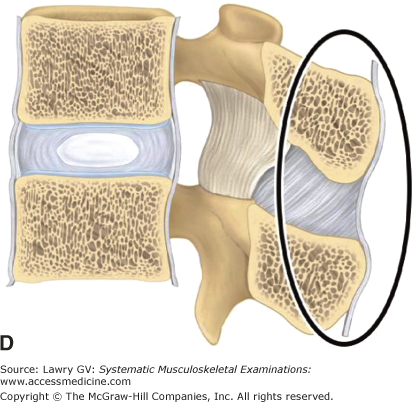

The intervertebral disks are shock-absorbing cushions between vertebral bodies which distribute weight over the surface of the vertebral end plates. They convert vertical loads into horizontal thrusts which are absorbed by the elastic mechanism of the disks. Concentric crossing layers of tough fibrous tissue, the annulus fibrosis, make up the outer circumference of the intervertebral disk, enclosing a central, gelatinous core, the nucleus pulposus (Fig. 7–3A through C).

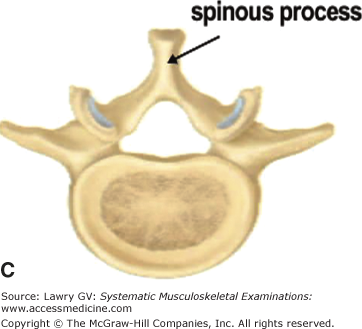

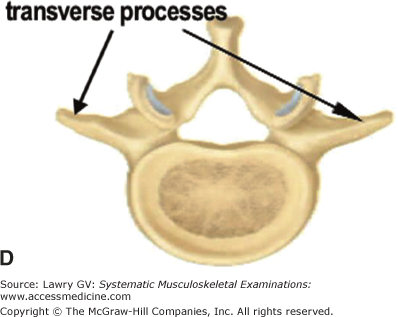

Posterior to the vertebral body is the neural arch. It is made up of two pedicles attached to the vertebral body and two laminae which fuse in the midline to form the posteriorly projecting spinous process and give rise (at the junction of the pedicle and lamina on each side) to the laterally directed transverse processes (Fig. 7–4A through D).

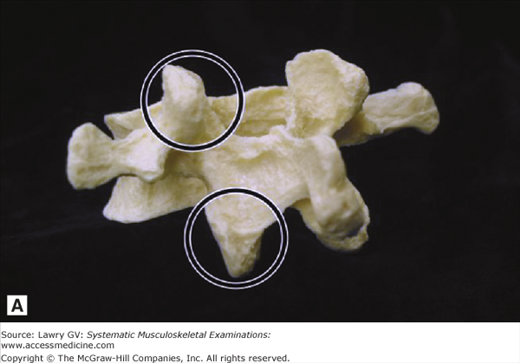

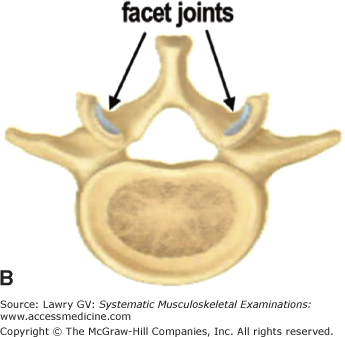

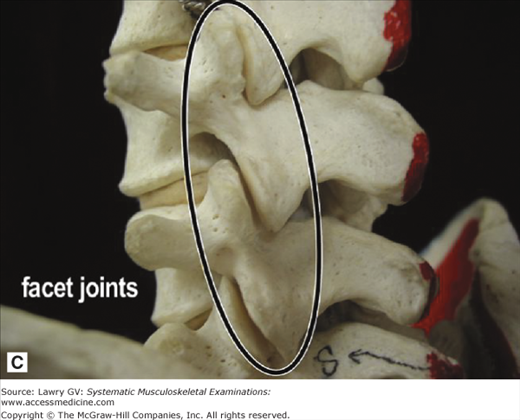

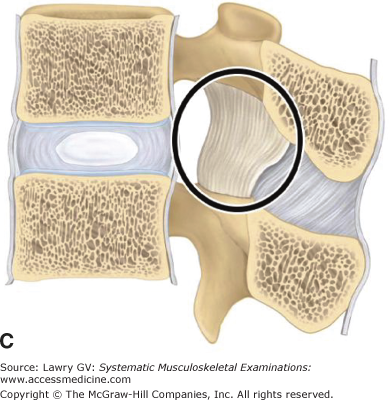

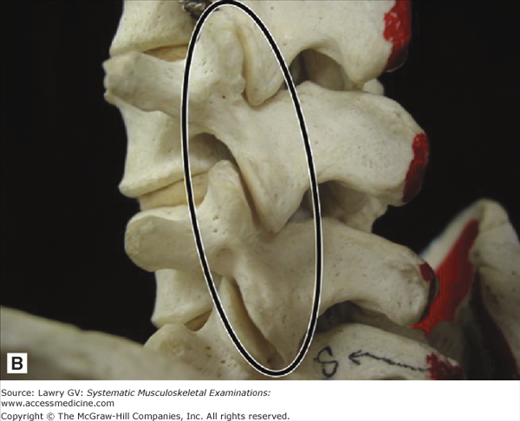

In addition to these bony projections, superior articular processes and inferior articular processes project from the junction of the pedicles and laminae forming the facet (apophyseal) joints (Fig. 7–5A through C) on each side. These “stacking joints” glide on one another during lateral movement of the spine and prevent sliding of one vertebra on another during flexion and extension.

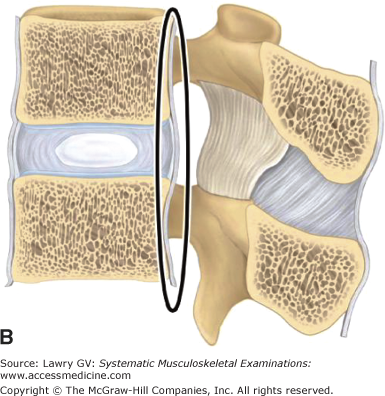

Two primary ligaments stabilize the anterior elements of the spinal column. The anterior longitudinal ligament is a broad, strong, fibrous band that runs from the occiput to the sacrum, where it anchors the anterior vertebral surfaces and intervertebral disks, preventing excessive extension of the spine (Fig. 7–6A). The posterior longitudinal ligament also runs the length of the spinal column but is a weaker and narrower band, broadening where it attaches posteriorly to the intervertebral disk (Fig. 7–6B).

Multiple ligaments also stabilize the posterior elements of the spine. The ligamentum flavum interconnects the vertebral laminae (the posterior roof of the spinal canal) and interspinous and supraspinous ligaments interconnect the spinous processes (Fig. 7–6C, D). These interconnecting ligaments partially limit forward and lateral flexion of the spine.

The larger cross-sectional area of the lumbar vertebral end plates facilitates load bearing by the intervertebral disks (Fig. 7–7A). Larger surface area of lumbar facet joints (apophyseal joints) provides increased torsional and sheer stability to these spinal segments, limiting rotation but allowing side bending (Fig. 7–7B). These features combine to allow the lumbar spine a significant range of motion, including flexion, extension, lateral bending, and rotation.

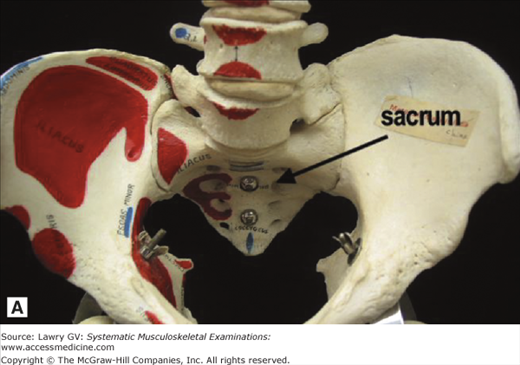

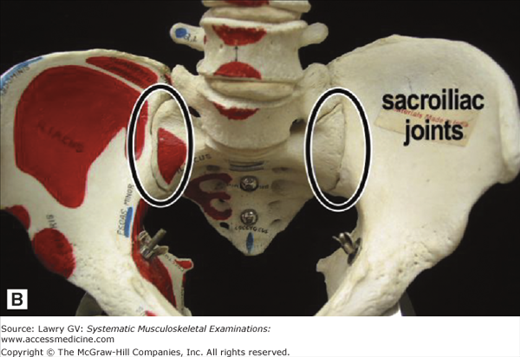

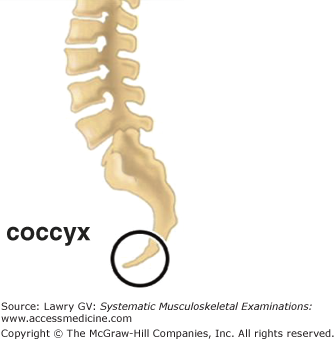

The wedge-shaped sacrum provides the interior anchor for the spinal column where it articulates with the posterior bony pelvis at the sacroiliac (SI) joints on each side (Fig. 7–8A, B). The sacroiliac joints are irregular, narrow articulations that join the spinal column to the pelvis on each side and lend stability to the posterior pelvic circle. The SI joints are both synovial and fibrous joints, which permit little or no movement (Fig. 7–9). The coccyx consists of four small fused vertebrae at the inferior end of the spinal column (Fig. 7–10).

The patient’s history is the essential first step in all musculoskeletal diagnosis and directs the focus of an appropriate physical examination. The musculoskeletal physical examination is used to confirm or refute diagnostic hypotheses generated by a thoughtful history. Appropriate evaluation of low back pain requires a careful delineation of pain characteristics and associated features. A helpful mnemonic to characterize low back pain is OPQRSTU where O = Onset, P = Precipitating and ameliorating factors, Q = Quality, R = Radiation, S = Severity, T = Timing, and U = Urinary symptoms.

Evaluation of low back pain centers on answering four important questions:

- Is there evidence of major trauma or injury?

- Is there evidence of neurologic compromise requiring surgical consultation?

- Is there an underlying serious systemic disease?

- Is there social or psychological distress that may amplify, prolong, or complicate the pain?

Major etiologic categories of diagnosis in patients presenting with low back pain include mechanical, systemic, and visceral disease.

- Mechanical factors: The vast majority of primary care visits for back pain are for uncomplicated, idiopathic, mechanical low back pain (back-predominant spinal pain). A fraction of patients present with mechanical low back pain complicated by neurologic features of sciatica or pseudoclaudication (lower extremity–predominant pain). In addition, low back pain may occasionally be secondary to spinal fractures: traumatic (younger individuals) or osteoporotic (older individuals).

- Systemic diseases: Low back pain is uncommonly associated with systemic problems, including neoplastic diseases, (metastatic malignancy and primary tumors), infectious diseases (osteomyelitis, diskitis, and abscess formation), and inflammatory spondylarthritis (ankylosing spondylitis and spondylarthropathies).

- Visceral diseases: Low back pain is uncommonly associated with gastrointestinal disease (peptic ulcer, gall bladder, and pancreatic diseases), genitourinary and gynecologic disorders (renal stones, renal infection, endometriosis, chronic pelvic inflammatory disease, and prostatitis), and arteriosclerotic vascular disease (abdominal aortic aneurism).

Most low back pain is attributed to muscle and/or ligamentous strain, facet joint arthritis, intervertebral disk herniation, or other miscellaneous causes. However, despite advances in imaging and neurodiagnosis, the etiology of most acute and chronic low back pain is complex and frequently poorly understood.

The thrust of a brief, focused history should inquire about risk factors pointing to fracture, malignancy, infection, underlying visceral or systemic disease, or the need for urgent surgical consultation. The musculoskeletal physical examination of the low back should be focused and used to confirm or refute diagnostic hypotheses generated by a focused, but thoughtful history.

Acute uncomplicated idiopathic neck and low back pain accounts for the vast majority of spinal pain seen in clinical practice. A focused clinical history and physical examination is important, and in the absence of serious underlying conditions, a diagnosis of acute nonspecific neck or low back pain can be made. A definitive anatomic diagnosis cannot be made in as many as 85% of patients presenting with acute neck or low back pain, but up to two-thirds of such patients have resolution of their symptoms in 4 to 8 weeks.

Fortified by this information, the clinician is able to direct subsequent management efforts at reassurance and resumption of normal functional activity rather than extensive and expensive (and frequently misleading) imaging studies.

The Examination, Overview

Observe the patient’s posture, movement, and behaviors throughout the history and different components of the physical examination.

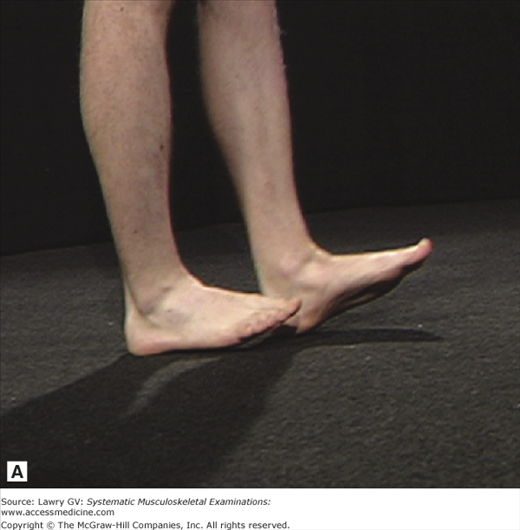

Begin by observing the patient’s gait. Note any uneven rhythm or asymmetry. Ask the patient to walk on heels and toes. Note any weakness or asymmetry. Observe the resting posture and alignment. Note any asymmetry or deformity. Inspect for the normal thoracic kyphosis and lumbar lordosis. Inspect the skin.

Next, assess skin tenderness to light touch and/or skin rolling over the lumbosacral region. Note the reaction pattern. Palpate the spinous processes from the mid-thoracic spine to the sacrum. Note any focal tenderness.

Observe lumbar flexion by instructing the patient to bend forward at the waist. Assess lumbar extension by having the patient bend backward. Assess lumbar lateral flexion (lateral bending) by asking the patient to bend to the right and to the left. Simulate lumbar spinal rotation by passively rotating the pelvis while keeping the shoulders and hips in the same plane or simulate axial loading by applying light pressure to the top of the skull. Note the reaction pattern.

Next, assess for the Trendelenburg sign on the right and left sides. Now, ask the patient to lie down.

Palpate for trochanteric bursitis (lateral trochanter). Next, palpate the insertion site of the gluteus medius tendon (posterior/superior trochanter) and the mid gluteus.

Assess hip flexion by grasping the heel and moving the thigh up toward the chest. Return the hip to 90° of flexion while holding the knee at 90° of flexion. Now, move the ankle medially to assess hip external rotation (ER) and move the ankle laterally to assess hip internal rotation (IR).

If indicated by the patient’s history or from observations during the basic examination, perform special testing for possible nerve root irritation.

With the patient lying down, perform a supine straight leg raise on both the symptomatic and nonsymptomatic sides. Estimate the angle at pain onset. Next, ask the patient to sit up. Check the knee and ankle reflexes. Assess strength by testing combined foot inversion and ankle dorsiflexion, great toe dorsiflexion, and foot eversion.

Next, assess a distracted, seated straight leg raise by “testing quadriceps strength” by bringing the knee into full extension and asking the patient to resist downward force applied to the shin. Note reaction pattern (as knee is brought into full extension).

If indicated by the patient’s history or from observations during the basic examination, complete your assessment by specifically noting the presence or absence of Waddell’s behavioral signs.

If indicated by the patient’s history or from observations during the basic examination, perform special testing for possible sacroiliitis or inflammatory spondyloarthropathy.

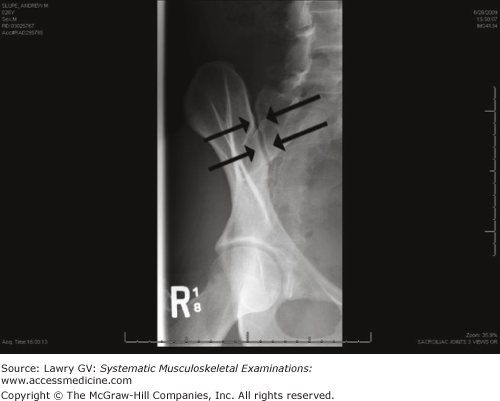

Ask the patient to stand. Palpate each sacroiliac joint. Note any tenderness. Then, measure lumbosacral spinal mobility by performing a “modified Schober test.” With the patient lying down, stress the sacroiliac joints by performing the FABER (hip flexion, abduction, and external rotation) maneuver. Note any SI region pain. Next, apply simultaneous downward compression to the iliac crests. Note any SI region pain. If a spondyloarthropathy is clinically indicated from the patient’s history and physical examination up to this point, also record spondylitis-specific measurements.

If indicated by the patient’s history or from observations during the basic examination, perform special testing for possible visceral or vascular disease.

The Examination, Component Parts

Gentleness and reassurance during the physical examination will establish a bond of trust and allow the patient to relax and give their best effort during each component of the examination. Observation of movement and pain-related behaviors during the history and physical examination is important and provides an opportunity to observe function and range of motion at a time when the patient is unaware that such observations are being made. Discrepancies may become apparent between the level of pain and function observed during the history and subsequent physical examination, providing important clues regarding the patient’s level of perceived distress.

The patient should be comfortable yet appropriately undressed. This usually includes undershorts with or without a gown for men and underwear with a gown for women. Adjusting the gown whenever necessary to permit adequate visualization is very important.

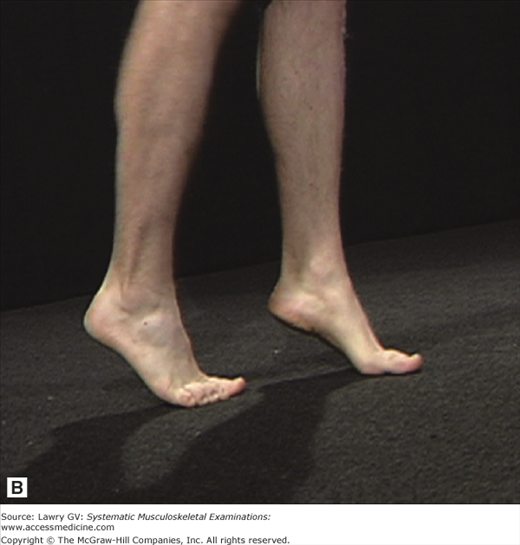

Observe the patient’s gait. Check for any limp or uneven rhythm. Note the swing and stance phases and any abnormal swaying of the trunk. Ask the patient to localize any pain during ambulation. Observe heel and toe walking. Note any asymmetry or weakness (Fig. 7–11A, B).

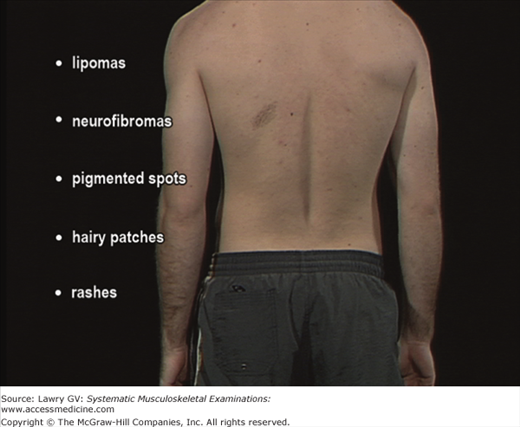

Next, observe standing posture and alignment. Note any asymmetry or deformity. Inspect the skin and note any scars from prior surgery or significant injury. Check for lipomas, neurofibromas, pigmented spots, or hairy patches in the lumbosacral region (sometimes associated with congenital structural abnormalities of the LS spine). Note any rashes (particularly vesicles characteristic of herpes zoster) (Fig. 7–12).

Lightly stroke or roll the skin on both sides of the lumbosacral spine. Note the patient’s response. Widespread sensitivity of the superficial soft tissues over the lumbar region (excluding prior scars) may be a sign of significant psychological distress (Fig. 7–13A). Beginning in the upper thoracic spine and proceeding inferiorly to the sacrum, palpate the spinous processes (Fig. 7–13B). If clinically indicated, palpation may be facilitated with the patient lying prone.