Abstract

Aim

To evaluate fear, beliefs, catastrophizing and kinesiophobia in chronic low back pain patients about to begin a training programme in a rehabilitation centre.

Patients and methods

Fifty chronic low back pain patients (including both males and females) were assessed in our physical medicine department. We used validated French-language scales to score the patients’ pain-related disability, quality of life and psychosocial factors.

Results

Seventy percent of the patients had a major functional disability (i.e., a Roland–Morris Scale score over 12) and nearly 73% reported an altered quality of life (the daily living score in the Dallas Pain Questionnaire). Pain correlated with functional impairment and depression but not with catastrophizing or kinesiophobia. Disability was correlated with catastrophizing and kinesiophobia.

Conclusion

Psychosocial factors are strongly associated with disability and altered quality of life in chronic low back pain patients. Future rehabilitation programs could optimizing patient management by taking these factors into account.

Résumé

Objectif

Étudier la prévalence des peurs et croyances, du catastrophisme et de la kinésiophobie chez des patients lombalgiques chroniques devant débuter un programme de réentraînement à l’effort en centre de rééducation.

Patients et méthodes

Cinquante patients lombalgiques chroniques des deux sexes ont eu, au cours d’un séjour en service de rhumatologie et médecine physique, une évaluation par des échelles adaptées et validées en français, du handicap, de la qualité de vie et des facteurs psychosociaux associés à leur lombalgie chronique.

Résultats

Dans la population étudiée, 70 % des patients avait un retentissement fonctionnel important (supérieur à 12 points sur l’échelle EIFEL) et près de 73 % avait une altération de la qualité de vie (composante activités quotidiennes de l’échelle DRAD). La douleur lombaire était associée à l’incapacité fonctionnelle et à la dépression mais pas avec le catastrophisme ou la kinésiophobie. Le handicap était corrélé au catastrophisme et à la kinésiophobie.

Conclusion

Les facteurs psychosociaux sont significativement associés au handicap et à l’altération de la qualité de vie du lombalgique chronique. Dans l’avenir, l’élaboration des programmes de rééducation pourrait tenir compte de l’importance des peurs et croyances, du catastrophisme et de la kinésiophobie pour une prise en charge optimale du lombalgique chronique.

1

English version

1.1

Introduction

In recent years, disability due to chronic low back pain (LBP) has steadily increased in all industrialized countries. Nearly 60% of the population is affected at some time and the socioeconomic burden is similar to that for very severe pathologies like coronary heart disease and diabetes mellitus . Maniadakis and Gray reported that direct economic burden of LBP was around £ 1.6 billion for the United Kingdom in 1998. Furthermore, the indirect burden of LBP (due to loss of productivity) has been estimated at about 6.5 times the direct cost. In the model described by Vlaeyen et al. in 1995 , chronic LBP leads to catastrophizing, fear of movement (kinesiophobia) and avoidance behaviour – all of which lead to deconditioning and the perpetuation of pain. Likewise, the French National Health Evaluation Agency has recently started reporting on the impact of psychosocial factors on long-term disability in chronic LBP . Over a third of the handicap burden may be linked to environmental and psychosocial factors . In the treatment of chronic LBP, the objectives are to reduce pain, improve function and minimize avoiding behaviour. Training can reduce pain and improve function, but today’s LBP treatment could be further improved by addressing concomitant psychosocial factors.

In this preliminary cross-sectional study, we assessed fear, beliefs, catastrophizing and kinesiophobia in chronic LBP patients who were about to begin a training course in a rehabilitation centre.

1.2

Patients and methods

1.2.1

Patients

We prospectively included 50 chronic LBP patients of both genders about to begin a training programme in a specialist rehabilitation centre. All subjects gave their informed consent to participation in a study whose protocol was very similar to the standard check-up performed in our rheumatology and physical medicine department. Hence, before going to the rehabilitation centre, each patient underwent a comprehensive clinical, radiological and biochemical evaluation. Functional disability, quality of life and psychosocial factors were evaluated with specific scales (the French-language versions of which have all been validated). We included adult patients (aged 18 or over) having suffered from non-specific LBP for at least the previous 3 months. The study exclusion criteria included neurological impairments, inflammatory or tumoral back conditions, a known, ongoing pregnancy and a history of psychiatric illness. For each patient, we noted the age, gender, past and present smoking habit, educational level, occupation, time out of work for the unemployed and any history of occupation accidents. In terms of clinical parameters, we measured the weight, height, finger-to-floor distance, Schöber Index, pain on a Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) and time since onset of LBP for each patient.

1.2.2

Disability scales, quality of life, psychosocial factors linked to LBP

We used validated French-language versions of the following scales to assess LBP-related functional disability, quality of life and psychosocial factors: the Roland–Morris Low Back Pain and Disability Questionnaire (RM) , the Dallas Pain Questionnaire (DPQ) , the Fear Avoidance Belief Questionnaire (FABQ) , the Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia (TSK) , the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS) and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HAD) . The RM scale evaluates the functional impact of LBP. It has 24 yes/no items to be ticked by the patient; the higher the number of ticked items, the greater the disability. The DPQ has four dimensions: “daily living”, “work-leisure”, “anxiety-depression” and “social interest”. The patient expresses his level of difficulty on a VAS. For each domain, the results are given as a percentage. The FABQ evaluates fear and beliefs when faced with pain. The questionnaire has a physical dimension and also addresses problems at work. Each item (noted from 0 to 6) is scored by the patient, who may “completely disagree” with the statement (a score of 0), “partially agree” to a varying extent (1 to 5) or “completely agree” (a score of 6). The TSK explores the fear of movement. Seventeen statements are scored on a four-point Likert Scale; the patient’s response can range from “strongly disagree” (with a score of 1) to “strongly agree” (with a score of 4). The PCS evaluates “thoughts and emotions” about pain. The patient may answer the PCS’s 13 questions by a giving a value ranging from 0 to 4, with the stated thought or emotion being “not at all” present (with a score of 0) through to “always” present (with a score of 4). Significant thresholds or cut-off values for each scale were taken from the literature .

1.2.3

Statistical analysis

An overall description of the study population was performed by giving the frequency of qualitative variables. Since the distribution of quantitative variables was not always Gaussian, we described them as the mean, standard deviation (S.D.), median, minimum, maximum and first and third quartile values.

Mean values were compared by using a Student’s t -test or Wilcoxon’s test (depending on the distribution) for quantitative variables and a Chi 2 test for qualitative variables. If a Chi 2 test could not be validly applied, it was replaced by a Fisher’s exact test. Correlations between continuous scales were quantified with Spearman correlation coefficient and the 95% confidence interval (CI) given by a Fisher transformation.

The threshold for statistical significance was set to 5% for all tests. The strength of correlations was taken into account according to the value of Rho ( R ), from R = ±0.5. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

1.3

Results

1.3.1

Low back pain and sociodemographic factors

Seventy percent of the 50 study subjects were male. The mean age was 50.2 ([range: 23–76] median: 52; S.D.: 11.48). The mean body mass index was 25.3 kg/m 2 ([16.7–44.9] median: 24.46, S.D.: 5.6). Forty-four percent of the patients stated that they were smokers (95% CI: 30.27–58.65) and 22% were heavy smokers, consuming more than 16.5 cigarettes per day ([2–40] median: 20; S.D.: 8.8). Less than half of the patients (44.9%) had reached college level (95% CI: 30.93–59.65) and 20.41% had attended primary school only (95% CI: 10.72–34.76). At the time of hospitalisation, 61.7 % of the study population was off work (95 % CI: 46.38–75.13) ( Tables 1 and 2 ).

| No. of patients | Patients (%) | 95% IC | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |||

| Females | 15 | 30.00 | 18.28–44.78 |

| Off-work | 29 | 61.70 | 46.38–75.13 |

| Tobacco | 22 | 44.00 | 30.27–58.65 |

| Study level | |||

| College | 22 | 44.90 | 30.93–59.65 |

| Secondary | 13 | 26.53 | 15.4–41.34 |

| Primary | 10 | 20.41 | 10.72–34.76 |

| Scales | |||

| RM > 12 | 35 | 70.00 | 55.22–81.72 |

| FABQ physical > 12 | 40 | 86.96 | 73.05–94.59 |

| FABQ work > 24 | 27 | 67.50 | 50.76–80.93 |

| DPQ daily living > 50 | 43 | 87.76 | 74.54–94.92 |

| DPQ leisure > 50 | 41 | 89.13 | 75.64–95.93 |

| DPQ anxiety-depression > 50 | 33 | 66.00 | 51.14–78.41 |

| DPQ social > 50 | 22 | 44.00 | 30.27–58.65 |

| TSK > 40 | 35 | 79.55 | 64.25–89.67 |

| PCS > 24 | 32 | 65.31 | 50.29–77.94 |

| HAD anxiety > 10 | 30 | 61.22 | 46.24–74.46 |

| HAD depression > 10 | 27 | 55.10 | 40.35–69.07 |

| Patients ( n ) | Mean | Standard deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical characteristics | |||

| Age (years) | 50 | 50.26 | 11.488788 |

| Time since onset of pain (months) | 50 | 116.9 | 149.02517 |

| VAS (0–100) | 47 | 60.382979 | 21.713103 |

| BMI (kg/m 2 ) | 50 | 25.317182 | 5.6018858 |

| Finger-to-floor distance (cm) | 50 | 24.64 | 23.82912 |

| Schöber (10 + cm) | 50 | 3.16 | 1.42657 |

| Cigarettes (number per day) | 22 | 16.590909 | 8.8997544 |

| Scales | |||

| RM | 50 | 13.94 | 4.7268663 |

| FABQ physical | 46 | 17.173913 | 6.0710766 |

| FABQ work | 40 | 27.1 | 13.755745 |

| DPQ daily living | 49 | 72.918367 | 16.873101 |

| DPQ leisure | 46 | 71.086957 | 17.729857 |

| DPQ anxiety depression | 50 | 56.92 | 25.68716 |

| DPQ social | 50 | 48.3 | 26.965776 |

| TSK | 44 | 46 | 9.5039771 |

| PCS | 49 | 29.020408 | 12.472453 |

| HAD overall | 49 | 20.632653 | 6.3988732 |

| HAD anxiety | 49 | 11.020408 | 4.4323141 |

| HAD depression | 49 | 9.6122449 | 2.863683 |

Low back pain had been present for an average of 116.9 months ([4–600] median: 42; S.D.: 149.02). However, it was not possible to establish the exact moment at which LBP per se specifically forced the subjects to stop working. The mean pain level on a VAS was 60.38 mm ([20–100] median: 60; S.D.: 21.71). For spinal parameters, the mean finger-to-floor distance was 24.6 cm ([0–100] median: 20; S.D.: 23.8). The mean Schöber Index was 3.16 cm ([0–65] median: 3; S.D.: 1.42).

1.3.2

Handicap, quality of life, fears and beliefs, catastrophizing and kinesiophobia

For functional disability, the mean RM score was 13.94 ([3–24] median: 14; S.D.: 4.72). Seventy percent of the patients had an RM score above 12. For the DPQ, the mean daily living score was 72.9% ([27–96] median: 78; S.D.: 16.8) and 87.76% of the patients had a score over 50% (95% CI: 73.05–94.59). For the physical domain (for 46 patients), the mean score was 17.17 ([0–24] median: 17; S.D.: 6.07) and 86.96% of patients (95% CI: 73.05–94.59) had a score over 12. For the TSK score, interpretation was possible for 44 patients, with an average of 46 ([19–65] median: 46; S.D.: 9.50); 79.55% of the patients (95% CI: 64.25–89.67) had a score over 40. For the PCS, 49 patients could be evaluated. The mean score was 29.02 ([4–42] median: 28; S.D.: 12.47) and 65.31% of patients (95% CI: 50.29–77.94) had a score over 24. For the HAD scale, the mean overall score was 20.63 ([9–36] median: 21; S.D.: 6.39). Anxiety and depression were separately evaluated; an anxiety score over 10 was found in 61.22% of patients and a depression score over 10 was found in 55.10% (95% CI: 40.35–69.07) ( Tables 1 and 2 ).

1.3.3

Statistical correlations between the various scales

When comparing the initial pain VAS score with the RM score, there was a significant difference ( p = 0.037) between patients with an RM score > 12 (mean pain score: 64.23 mm) and those with a score < 12 (mean pain score: 49.17). The difference in initial VAS was equally significant ( p = 0.029) when comparing patients with a FABQ physical activity score over 12 (mean pain score: 62.58 mm) and those with a score under 12 (mean pain score: 41.67 mm). For the HAD scale depression items, there was a significant difference ( p = 0.023) in initial VAS when comparing patients with a depression score above 10 (mean pain score: 67.04) and those below 10 (mean pain score: 52.25). Other comparisons between the initial pain VAS score, disability scores, fears, beliefs, kinesiophobia and catastrophizing did not reveal any significant correlations.

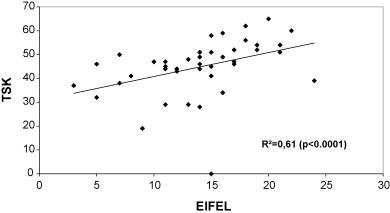

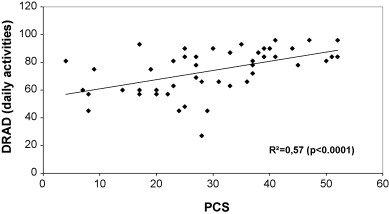

The difference in the mean initial VAS came close to statistical significance for the daily living ( p = 0.057) and social interest domains ( p = 0.054) of the DPQ ( Table 3 ). When comparing the time with LBP and the RM score, there was a statistically significant difference ( Table 4 ) between patients with RM score over 12 (mean LBP duration: 143.63 months) and those with a score under 12 (mean LBP duration: 54.53 months) ( p = 0.041). Patients who were out of work also had a significantly higher RM score than those who were still working at the time of study entry ( p = 0.036). There was also a statistically significant difference concerning finger-to-floor distance when comparing patients with a DPQ daily living score over 50% and the others ( p = 0.039). In terms of the disability scales, there was a correlation between the RM score and the DPQ daily living score ( R = 0.52, p = 0.0001) and between the RM score and the DPQ leisure domain score ( R = 0.62, p = 0.0001). When relating the quality of life, functional impairment, fears and beliefs, kinesiophobia and catastrophizing scores, R was 0.60 for RM versus TSK ( Table 5 , Fig. 1 ) and 0.57 for DPQ daily living versus PCS ( Table 5 , Fig. 2 ). Social and leisure activities were correlated in scales DPQ and TSK and the social interest and anxiety were correlated in the DPQ and the PCS. The overall HAD score correlated with the DPQ’s social interest, leisure and anxiety items and also with the TSK and PCS scores. The same correlations were seen with the anxiety HAD score, with the exception of the DPQ leisure items. The HAD depression score was only correlated with the social interest and anxiety domains on the DPQ ( Table 6 ).

| RM < 12 | RM > 12 | p | FABQ < 12 | FABQ > 12 | p | HAD depression < 10 | HAD depression > 10 | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VAS | Mean | 49.17 | 64.23 | 0.037 | 41.67 | 62.58 | 0.029 | 52.25 | 67.04 | 0.023 |

| Standard deviation | 23.14 | 20.12 | 14.72 | 21.96 | 20.55 | 21.05 |

| RM < 12 | RM > 12 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time since onset of pain (mean ± standard deviation) | 54.53 ± 76.12 | 143.63 ± 164.83 | 0.041 |

| Off-work ([ n ] % patients) | 6 (40.00%) | 23 (71.88%) | 0.036 |

| Spearman’s correlation coefficients | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DPQ | DPQ anxiety | DPQ social | TSK | PCS | ||

| Leisure | Daily living | |||||

| RM | 0.62993 | 0.52247 | 0.41649 | 0.43084 | 0.60496 | 0.46445 |

| < 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0026 | 0.0018 | < 0.0001 | 0.0008 | |

| 46 | 49 | 50 | 50 | 44 | 49 | |

| DPQ daily living | 0.65918 | 0.48558 | 0.43671 | 0.41670 | 0.57217 | |

| < 0.0001 | 0.0004 | 0.0017 | 0.0054 | < 0.0001 | ||

| 46 | 49 | 49 | 43 | 48 | ||

| DPQ leisure | 1.00000 | 0.54080 | 0.48014 | 0.54215 | 0.44233 | |

| 0.0001 | 0.0007 | 0.0003 | 0.0023 | |||

| 46 | 46 | 46 | 41 | 45 | ||

| DPQ anxiety | 0.54080 | 1.00000 | 0.66500 | 0.39600 | 0.53581 | |

| 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | 0.0078 | < 0.0001 | |||

| 46 | 50 | 50 | 44 | 49 | ||

| DPQ social | 0.48014 | 0.66500 | 1.00000 | 0.58005 | 0.53843 | |

| 0.0007 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | |||

| 46 | 50 | 50 | 44 | 49 | ||

| Spearman’s correlation coefficients | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| HAD overall | HAD anxiety | HAD depression | |

| RM | 0.47075 | 0.45082 | 0.29947 |

| 0.0006 | 0.0012 | 0.0366 | |

| 49 | 49 | 49 | |

| FABQ physical | 0.16181 | 0.13497 | 0.14105 |

| 0.2883 | 0.3767 | 0.3554 | |

| 45 | 45 | 45 | |

| FABQ work | 0.21006 | 0.19476 | 0.15166 |

| 0.1933 | 0.2285 | 0.3502 | |

| 40 | 40 | 40 | |

| DRAD daily living | 0.49045 | 0.37697 | 0.48565 |

| 0.0004 | 0.0083 | 0.0005 | |

| 48 | 48 | 48 | |

| DRAD leisure | 0.50889 | 0.41746 | 0.49224 |

| 0.0004 | 0.0043 | 0.0006 | |

| 45 | 45 | 45 | |

| DRAD anxiety | 0.70443 | 0.65641 | 0.58042 |

| < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | |

| 49 | 49 | 49 | |

| DRAD social | 0.62123 | 0.54123 | 0.55942 |

| < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | |

| 49 | 49 | 49 | |

| TSK | 0.54315 | 0.57321 | 0.31486 |

| 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | 0.0374 | |

| 44 | 44 | 44 | |

| PCS | 0.69498 | 0.70612 | 0.42852 |

| < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 | 0.0024 | |

| 48 | 48 | 48 | |

1.4

Discussion

This preliminary study explored the prevalence of fears, beliefs, catastrophizing and kinesiophobia in patients with chronic LBP at the time of a hospital check-up and prior to an intensive retraining programme at a rehabilitation centre.

The patient profile (in terms of age, gender, smoking habits, educational level, time off work and duration of LBP) was very similar to those recorded in analogous investigations . The fact that we recruited patients from a specialist physical medicine department may explain the long observed duration of LBP, the long time out of work, the high level of pain and the poor spinal index. In the study by Genêt et al. , recruitment was performing in general medicine and by rheumatology and physical medicine specialists; accordingly, patients were less severely affected (mean duration of LBP: 47.6 months; time off work: 1.9 months). The markedly higher level of disability in our patients was most clearly revealed by the RM scale score (i.e., more than 87% of the subjects with a score over 50%) and the physical component of the FABQ (with more than 86% over 12 points).

Our results agree fully with those of Verbunt et al. , who used a similar recruitment method (with an average RM score of 11.4 ± 5.4). The handicap was also severe, with kinesiophobia (mean TSK score: 46), catastrophizing (mean PCS score: 29.02) and anxiety-depression (mean overall HAD score: 20.63). Elfving et al. treated patients in a primary rehabilitation centre for chronic LBP. The parameters were significantly less severe, with a mean overall TSK score of 27 (16–47) and a mean PCS score of 12.5 (1–44). In fact, 80% of the patients included in this Scandinavian study were still at work.

In the present study, LBP (evaluated on a pain VAS) correlated closely with functional disability. This finding contrasts with that of Reneman et al. , who concluded as to a slight or an even non-existent link between pain and disability in chronic LBP. However, the relationship between pain and depression observed in our present study was also recently reported by Bair et al. , who also noted that the patients with the highest depression and anxiety scores also suffered the most pain. We did not find any relationship between pain, kinesiophobia and catastrophizing. This result suggests that pain may not be the main reason for fearing movement in chronic LBP. Functional disability appears to be independently determined by pain on one hand and kinesiophobia/catastrophizing on the other . We also found correlations between the duration of LBP, time since stopping work and functional impairment. This testifies to physical deconditioning and the now well-established need to limit time off work in LBP patients . Valat et al. showed that patients having been off work for a long times were more likely to evolve towards chronic LBP .

In the present work, the functional impact of LBP (as evaluated by the RM score) was strongly correlated with kinesiophobia. This finding disagrees with the recent study by Huijnen et al. . However, this discrepancy may be due to the fact that the authors used the Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale, rather than the RM questionnaire. In fact, their population was very similar to ours, with mean duration of LBP of 156.5 months ([18–444] S.D.: 116) and kinesiophobia rated at 41.8 on the TSK scale (compared with 46 in our study).

Concerning catastrophizing and the impact on daily living, there was a strong correlation between the PCS score and the DPQ daily living items. This is not often reported in literature – probably because the DPQ is not often used to measure psychosocial factors in LBP. Kovacs et al. did not find a true impact of catastrophizing on ordinary daily living, although their study population was older than ours.

In fact, the correlation between the overall HAD score and catastrophizing/kinesiophobia was due to the HAD scale’s anxiety items and was not found when considering the depression components alone. Hence, anxiety seems to be required for the generation of catastrophizing in the LBP patient and reduces his/her control of the situation.

Our preliminary study confirmed the importance of psychosocial factors linked to chronic LBP. We now intend to evaluate the change over time in these factors after effort retraining in a rehabilitation centre and correlate them with physical parameters (pain on a VAS, finger-to-floor distance and the Schöber Index). We shall also try to determine criteria that are predictive of successful rehabilitation. These will primarily social parameters, such as the type of work, cognitive and psychological ability to adapt or change work tasks and the extent of fears, beliefs, catastrophizing and kinesiophobia at the start of the training programme. The initial assessment of LBP patients should ideally include a psychological evaluation. Graphic representation of the body and the pain may help to explain kinesiophobia (at least in part) in terms of destruction of the body scheme and an altered mechanical vision of the body . We believe that it will be important to pay specific attention to psychosocial factors during rehabilitation because the latter may account for 20% of the functional impairment in LBP .

Acknowledgements

We thank Sylvie Rozenberg and Marc Marty for their advice on defining statistically significant thresholds when evaluating LBP scales.

2

Version française

2.1

Introduction

L’invalidité induite par la lombalgie chronique n’a cessé de croître ces dernières années dans tous les pays industrialisés. Près de 60 % de la population sont concernés par la lombalgie et son coût socioéconomique est devenu analogue à celui de pathologies chroniques réputées plus graves comme les coronaropathies et le diabète sucré . Maniadakis et Gray ont évalué en 1998 au Royaume-Uni le coût direct des dépenses de soins liées à la lombalgie chronique à £ 1632 millions. Les coûts indirects, liés à la perte de productivité, sont beaucoup plus importants encore, représentant plus de 6,5 fois les coûts directs. Dans le modèle décrit par Vlaeyen en 1995 , la douleur lombaire induit un catastrophisme conduisant à la peur du mouvement (kinésiophobie) et à des conduites d’évitement favorisant le déconditionnement et la pérennisation des douleurs. En France également, l’attention des autorités sanitaires a été attirée, depuis quelques années, sur l’importance des facteurs psychosociaux dans la pérennisation du handicap chez le lombalgique chronique . Les facteurs psychosociaux sont plus importants que les facteurs physiques et mécaniques dans l’installation du handicap fonctionnel du lombalgique. Plus d’un tiers de la variance du handicap lombaire serait lié à ces facteurs environnementaux et psychosociaux .

Chez le lombalgique chronique, les objectifs du traitement sont de réduire la douleur, d’améliorer la fonction et de diminuer les conduites d’évitement. Le reconditionnement à l’effort a des effets bénéfiques sur la douleur et la fonction, mais l’effet de ce traitement pourrait être optimisé par l’inclusion dans le programme de techniques visant à réduire l’importance des facteurs psychosociaux associés à la lombalgie chronique.

Dans ce travail préliminaire, l’importance des peurs et croyances, du catastrophisme et de la kinésiophobie a été évaluée, de manière transversale, dans un groupe de patients débutant un stage de reconditionnement à l’effort en centre de rééducation.

2.2

Patients et méthodes

2.2.1

Patients

Cinquante patients lombalgiques des deux sexes devant être adressés en centre de rééducation pour un stage de réentraînement à l’effort ont été inclus de façon prospective dans l’étude. Tous les patients ont donné leur consentement éclairé avant de participer à l’étude, dont le protocole ne différait pas du bilan et de la prise en charge habituellement réalisés dans le service. Avant d’aller en centre, chaque patient a eu une évaluation clinique, radiologique et biologique en service de rhumatologie et médecine physique. Une évaluation de l’incapacité fonctionnelle, de la qualité de vie et des facteurs psychosociaux a été réalisée par des échelles spécifiques validées en français. Pour être inclus, les patients devaient avoir une lombalgie non spécifique évoluant depuis plus de trois mois et être âgés de plus de 18 ans. Les critères d’exclusion étaient la présence d’un déficit neurologique, une origine inflammatoire ou tumorale de la lombalgie, une grossesse en cours, des antécédents psychiatriques. Pour chaque patient était précisé l’âge, le sexe, l’existence d’un tabagisme actuel ou passé, le niveau scolaire, l’activité professionnelle, l’existence d’un arrêt ou d’un accident de travail. Les paramètres physiques enregistrés étaient le poids, la taille, la distance doigts–sol et l’indice de Schöber. La durée de la lombalgie était précisée ainsi que le niveau de douleur sur l’échelle visuelle analogique (EVA).

2.2.2

Échelles de handicap, de qualité de vie et facteurs psychosociaux associés à la lombalgie

Les échelles d’évaluation, validées en français, d’incapacité fonctionnelle, de qualité de vie et de critères psychosociaux associés à la lombalgie étaient l’EIFEL , le DRAD , le Fear Avoidance Belief Questionnaire (FABQ) , le Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia (TSK) , le Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS) et le Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HAD) .

L’EIFEL est un questionnaire d’évaluation du retentissement fonctionnel des lombalgies comportant 24 items auxquels le patient répond en cochant ou non une case correspondant à une affirmation donnée sur son handicap lombaire. Plus le nombre d’items cochés est élevé et plus le handicap lombaire est important. Le DRAD est la traduction française de l’autoquestionnaire de Dallas. Il comporte quatre dimensions (activités quotidiennes, activité professionnelle et loisirs, anxiété-dépression et sociabilité). Le patient répond sur une échelle visuelle en fonction de la gêne qu’il ressent. Les résultats sont exprimés en pourcentage pour chaque dimension. Le FABQ est une échelle d’évaluation exprimant les peurs et croyances face à la douleur. Le questionnaire comporte une dimension physique et une dimension travail dont les items, cotés de 0 à 6, doivent être entourés par le patient selon qu’il est « absolument pas d’accord avec la phrase » (0), « partiellement d’accord avec la phrase » (1 à 5) ou « complètement d’accord avec la phrase » (6). Le TSK évalue l’importance de la peur du mouvement. Il comporte 17 affirmations, cotées de 1 à 4, avec lesquelles le patient peut être « complètement en désaccord » (1) jusqu’à « complètement en accord » (4). Le PCS est une échelle de catastrophisme qui évalue « les pensées et émotions » que peuvent ressentir les patients face à la douleur. Elle comporte 13 questions auxquelles il faut répondre par un chiffre allant de 0 à 4, selon que la pensée ou l’émotion exprimée dans l’item est « pas du tout » (0) à « tout le temps » (4) en accord avec le vécu du patient. L’échelle HAD est un autoquestionnaire de 14 questions évaluant séparément l’anxiété et la dépression. Pour chaque item, le patient doit choisir sa réponse parmi quatre propositions cotées de 0 à 4. Pour chacune de ces échelles, des seuils de significativité ( cut-off ) ont été fixés, en fonction des données publiées dans la littérature .

2.2.3

Analyse statistique

Une description globale de l’ensemble de l’échantillon a été réalisée en donnant les fréquences des différentes catégories pour les variables qualitatives. Les distributions des variables quantitatives n’étant pas toujours gaussiennes, la description de ces variables a été faite à l’aide de la moyenne et de l’écart-type mais aussi de la médiane, des valeurs minimales et maximales et des interquartiles (75 e et 25 e centiles).

Les comparaisons entre les échelles et les scores ont été réalisées à l’aide des tests de comparaison de moyennes (Student ou Wilcoxon en fonction de la distribution) pour les variables quantitatives et à l’aide d’un test du Chi 2 pour les variables qualitatives. Lorsque les conditions de validité du Chi 2 n’étaient pas respectées, celui-ci a été remplacé par le test exact de Fisher.

Les corrélations entre échelles continues ont été quantifiées à l’aide du coefficient de corrélation des rangs de Spearman assorti d’un intervalle de confiance à 95 % (IC 95 %), calculé par une transformation de Fisher.

Le seuil de signification a été fixé à 5 % pour tous les tests utilisés. L’importance des corrélations a été prise en compte, en fonction de la valeur de Rho ( R ), à partir de R = ±0,5.

L’analyse statistique a été réalisée avec le logiciel SAS version 9 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, États-Unis).

2.3

Résultats

2.3.1

Caractéristiques sociodémographiques et de la lombalgie

Parmi les 50 patients inclus dans l’étude, 70 % étaient des hommes. Les patients étaient âgés en moyenne de 50,2 ans ([23–76] médiane : 52 ; écart-type : 11,48). L’indice de masse corporelle moyen était de 25,3 kg/m 2 ([16,7–44,9] médiane : 24,46 ; écart-type : 5,6). Quarante-quatre pour cent des patients signalaient être fumeurs (IC 95 % : 30,27–58,65). Vingt-deux patients étaient des fumeurs actifs, consommant en moyenne 16,5 cigarettes par jour ([2–40] médiane : 20 ; écart-type : 8,8). Moins de la moitié (44,9 %) des patients avait atteint le niveau d’étude du collège (IC 95 % : 30,93–59,65), alors que 20,41 % n’avait qu’un niveau scolaire primaire (IC 95 % : 10,72–34,76). Au moment de l’hospitalisation, 61,7 % de la population globale étaient en arrêt de travail (IC 95 % : 46,38–75,13) ( Tableaux 1 et 2 ).