The History and Development of Total Elbow Arthroplasty

Matthew L. Ramsey

INTRODUCTION

The basic requirement for normal elbow function is a painfree, mobile, and stable articulation. Compromise of one or more of these basic elements results in functional impairment of the elbow. Many surgical strategies have been developed to manage disorders of the elbow. Arthritic conditions of the elbow, posttraumatic conditions, and destruction of the elbow following infection were the predominant pathologies prior to the development of elbow arthroplasty. Nonreplacement surgeries for the management of painful, disabling conditions of the elbow included resection arthroplasty, interposition arthroplasty, and arthrodesis.

Elbow arthroplasty was borne out of the failures of nonreplacement surgeries to effectively treat articular and periarticular pathologies. To understand the factors pressing the development of modern total elbow arthroplasties, an understanding of the problems that fueled the need for joint replacement must be appreciated.

Resection arthroplasty involves excision of a portion of or all of the articular surfaces of the elbow. Many methods for resection arthroplasty have been described. The common limiting factor in all of these methods was instability limiting functional use of the extremity. Interposition arthroplasty was established as a refinement to resection arthroplasty because there was increased stability by establishing a fixed fulcrum for elbow motion by resurfacing the joint surface. Sepsis, instability, or reankylosis have been reported as complications of this method. In the past, spontaneous ankylosis of the elbow occurred as the sequela of infection, trauma, or rheumatoid arthritis. It is interesting that many of the nonreplacement surgeries previously discussed attempt to restore motion in these patients because of the profound disability of a stiff elbow. As an intended surgical treatment, ankylosis seeks to provide stability and pain relief through rigid union of the humerus to the ulna. The functional disability resulting from arthrodesis limits its current application to disorders of the elbow.

The functional limitations of nonreplacement surgeries fueled early efforts at elbow replacement. The motivation for the development of replacement surgeries was to provide a more predictable treatment to alleviate pain and improve function. These early efforts were characterized by metallic hemiarthroplasties of the distal humerus or proximal

ulna and distal humerus or proximal ulnar-bearing surfaces constructed of nylon, rubber, or acrylic. Fixation of these implants to bone was achieved through uncemented intramedullary stems or extramedullary supports screwed into cortical bone. Instability, early loosening, and unpredictable range of motion limited the success of these implants.

ulna and distal humerus or proximal ulnar-bearing surfaces constructed of nylon, rubber, or acrylic. Fixation of these implants to bone was achieved through uncemented intramedullary stems or extramedullary supports screwed into cortical bone. Instability, early loosening, and unpredictable range of motion limited the success of these implants.

The earliest efforts at total elbow arthroplasty (TEA) were custom designs replacing the ulnohumeral joint for bone loss and destruction of the elbow resulting in instability. These early attempts at hinged elbow arthroplasty predated the introduction of polymethylmethacrylate. Additionally, the elbow was felt to function as a rigid hinge. This view proved a major limitation in the replication of normal elbow mechanics. The combination of poor implant fixation to bone and inferior implant design contributed to high failure rates from early loosening.

The modern era of total elbow replacement was initiated in 1972 when Dee implanted a cemented hinged replacement. The period of time following Dee’s achievement was characterized by a rapid evolution in the understanding of elbow biomechanics, surgical techniques, and improvements in implant materials and design.

Modern techniques of elbow replacement have evolved substantially over the last several decades and continue to evolve today. Although Dee is credited with ushering in the modern era of elbow replacement in the early 1970s, his achievements would have been impossible without the efforts of a number of surgeons who preceded him. The pioneering work of countless surgeons who were driven to provide patients with surgical solutions to difficult problems formed the foundation for further advances in implant design. To fully appreciate the current state of elbow replacement, an understanding of the historical developments leading to these modern techniques is necessary.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Destruction of the elbow joint is a problem that has existed through the ages, yet the underlying causes of joint destruction are varied. The common thread linking all of these disease processes is destruction of the ulnohumeral joint, which compromises normal function of the elbow. The manifestation of destruction of the ulnohumeral joint may be painful motion, instability, or even ankylosis.

The bony structures that may be involved in the disease process are the articular surfaces, subchondral bone, and supracondylar bony columns. Progressive involvement of the subchondral bone and supracondylar bony columns introduces elements of bone loss that will affect stability of the elbow joint. Bony instability is rarely of clinical significance if only the articular surface is involved. Progressive bone loss beyond the articular surface compromises the stability of the fulcrum required for stable elbow motion, leading to varying degrees of dysfunctional instability.

The soft tissues include the ligaments and muscles that stabilize and provide power to the elbow and the neurovascular structures that provide sensation and motor strength to the extremity. Involvement of these soft-tissue structures varies with the underlying pathology from laxity of the collateral ligaments in rheumatoid arthritis to contracture or near ankylosis in posttraumatic conditions of the elbow. A requirement for a functional elbow following TEA is functioning elbow flexors. Loss of the triceps mechanism compromises elbow function but is not a contraindication for TEA. Loss of the triceps does limit useful overhead function or activities that require active extension.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT OF THE ELBOW

Surgery for ankylosis, instability, or painful motion of the elbow can be divided along a time line into two broad categories: nonreplacement surgery and replacement surgery. Prior to the 1970s nonreplacement surgery predominated for pathologic conditions of the elbow. The development and application of modern joint replacement techniques to the elbow have expanded the ability to treat a variety of ailments of the elbow and allowed the refinement of the indications for nonreplacement surgery of the elbow. A review of the nonreplacement surgeries of the elbow and the issues that pressed the development of replacement surgery of the elbow allows an appreciation of the progress made to date.

Nonreplacement Surgery of the Elbow

Resection Arthroplasty

According to Dee (1), resection arthroplasty was described as early as 1780 by Park of Liverpool and Moreau of France. The surgery they described undertook aggressive extraperiosteal resection of the entire elbow joint (Fig. 18-1). Ollier (2) advocated a less aggressive resection of the distal humerus and proximal ulna in an attempt to avoid the high rates of instability that accompanied extraperiosteal resection. Regardless of the technique of resection, instability was a common occurrence following surgery because scar tissue at the site of bony resection was all that maintained joint stability.

Since these early reports a number of authors reported satisfactory results with this method (3, 4, 5). Buzby (3) favored resection arthroplasty over interposition arthroplasty and reported satisfactory results in 13 of 15 cases of resection for tuberculosis and posttraumatic ankylosis. He felt there was no advantage to interposition arthroplasty, which often resulted in a few degrees of stable motion with pain compared to a resected elbow if only moderately flail and painfree. Kirkaldy-Willis (5) reported satisfactory results in five of eight patients with posttraumatic ankylosis and four of six patients with ankylosis following tuberculosis

infection. Patients without atrophy of the elbow flexors and extensors attained full motion with good lateral stability when compared to those with profound, longstanding muscle atrophy. Resection arthroplasty, with and without skin interposition, was used by Hurri and colleagues to treat 71 patients (76 cases) with rheumatoid arthritis (4). The indication for surgery was a stiff elbow in 59 cases and severe pain or locking in 17 cases. Joint stability was better in the group with skin interposition because resecting less proximal ulna retained a fulcrum for elbow motion. Overall, 64% of the resection group was painfree compared to 40% of the skin interposition group. It appears that the pain relief afforded by resection arthroplasty often came at the expense of instability. Conversely, the improved stability with interposition arthroplasty is accompanied by less predictable pain relief.

infection. Patients without atrophy of the elbow flexors and extensors attained full motion with good lateral stability when compared to those with profound, longstanding muscle atrophy. Resection arthroplasty, with and without skin interposition, was used by Hurri and colleagues to treat 71 patients (76 cases) with rheumatoid arthritis (4). The indication for surgery was a stiff elbow in 59 cases and severe pain or locking in 17 cases. Joint stability was better in the group with skin interposition because resecting less proximal ulna retained a fulcrum for elbow motion. Overall, 64% of the resection group was painfree compared to 40% of the skin interposition group. It appears that the pain relief afforded by resection arthroplasty often came at the expense of instability. Conversely, the improved stability with interposition arthroplasty is accompanied by less predictable pain relief.

Figure 18-1 Extraperiosteal resection arthroplasty of the elbow. (From Wadsworth TG, ed. The elbow. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1982, with permission.) |

All reports of resection arthroplasty have identified instability as a complication of this procedure. Currently, resection arthroplasty is considered a salvage procedure in patients with uncontrollable infections and in patients with failed TEA.

Interposition Arthroplasty

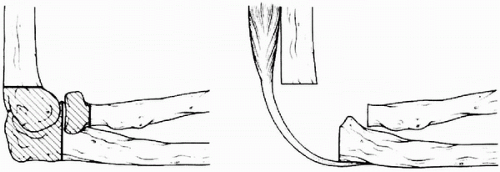

Interposition arthroplasty was introduced as a refinement of resection arthroplasty in which fascia was laid between the surfaces of the distal humerus and proximal ulna and less bone was excised (Fig. 18-2). The intention was to prevent joint instability by creating a fulcrum between the distal humerus and olecranon fossa. Additionally, the interposition of fascia, fat, skin, or any other material provided a spacer that allowed full, painfree motion.

Originally introduced by Defontaine (6) in 1887, this technique was popularized in the United States by Murphy (7). Murphy reported satisfactory results in 60 patients using fat and fascia as an interposition material. MacAusland (8) and Campbell (9) were early proponents of this technique. MacAusland (8) reviewed the literature on the treatment of elbow ankylosis and reported his experience with interposition arthroplasty to manage the ankylosed elbow. The indications for interposition arthroplasty included ankylosis as a sequela of infection or trauma. Sufficient bone was removed to allow mobilization of the joint, but excessive bone resection was avoided in an effort to minimize postoperative instability. Loss of motion in the postoperative period necessitating manipulation was a common problem, and reankylosis of the elbow occurred in a minority of the patients. Instability was not a problem in the early experience with this technique.

Whereas instability was not a problem in the early experience with interposition arthroplasty, a tendency for postoperative stiffness prompted a modification of the technique of interposition arthroplasty by Hass (10). Previous approaches attempted to maintain joint congruity by resecting only enough bone to allow joint mobilization but not so much bone to cause instability. Haas fashioned the distal humerus into a sharp wedge that articulated with a shallow trough in the olecranon fossa (Fig. 18-3). By minimizing intraarticular bone contact, it was felt that the tendency for reankylosis of the joint would be minimized. Despite these modifications, reankylosis occurred, resulting in an unsatisfactory result. Postoperative radiographs demonstrated adaptive changes of the resected bone ends according to the functional demands of the elbow. Knight and Van Zandt treated 45 patients with interposition arthroplasty. They reported satisfactory results in a slight majority of patients (11). Sepsis, instability, or reankylosis caused the poor results in this study. The best results were demonstrated in patients with posttraumatic arthritis of the elbow.

The application of interposition arthroplasty to patients with rheumatoid arthritis helped define the current role of this technique. Unander-Scharin and Karlholm treated 19 patients with fat interposition, a majority with rheumatoid arthritis (12). Some patients with rheumatoid arthritis had reasonable, but painful, motion of the elbow. The authors concluded that in this group of patients, interposition arthroplasty was not a satisfactory treatment.

A review of the Mayo Clinic experience with the surgical management of rheumatoid arthritis highlighted the

spectrum of pathology encountered in the rheumatoid elbow (13). At one end of the spectrum are those patients that require surgery to address the mechanics of a deranged joint; at the other extreme are those patients who present with pain. We found that in patients with rheumatoid arthritis where pain was the predominant complaint, a more limited procedure consisting of synovectomy and radial head excision provided better results than an extensive joint debridement with interposition. A number of subsequent reports support this conclusion and report satisfactory results in up to 75% of patients at an average of 4.5 years from the procedure (13, 14, 15, 16, 17).

spectrum of pathology encountered in the rheumatoid elbow (13). At one end of the spectrum are those patients that require surgery to address the mechanics of a deranged joint; at the other extreme are those patients who present with pain. We found that in patients with rheumatoid arthritis where pain was the predominant complaint, a more limited procedure consisting of synovectomy and radial head excision provided better results than an extensive joint debridement with interposition. A number of subsequent reports support this conclusion and report satisfactory results in up to 75% of patients at an average of 4.5 years from the procedure (13, 14, 15, 16, 17).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree