Abstract

The Field of Competence (FOC) of specialists in Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine (PRM) in Europe follows uniform basic principles described in the White Book of PRM in Europe. An agreed basis of the field of competence is the European Board curriculum for the PRM-specialist certification. However, due to national traditions, different health systems and other factors, PRM practice varies between regions and countries in Europe. Even within a country the professional practice of the individual doctor may vary because of the specific setting he or she is working in. For that reason this paper aims at a comprehensive description of the FOC in PRM. PRM specialists deal with/intervene in a wide range of diseases and functional deficits. Their interventions include, prevention of diseases and their complications, diagnosis of diseases, functional assessment, information and education of patients, families and professionals, treatments (physical modalities, drugs and other interventions). PRM interventions are often organized within PRM programmes of care. PRM interventions benefit from the involvement of PRM specialists in research. PRM specialists have knowledge of the rehabilitation process, team working, medical and physical treatments, rehabilitation technology, prevention and management of complications and methodology of research in the field. PRM specialists are involved in reducing functional consequences of many health conditions and manage functioning and disability in the respective patients. Diagnostic skills include all dimensions of body functions and structures, activities and participation issues relevant for the rehabilitation process. Additionally relevant contextual factors are assessed. PRM interventions range from medication, physical treatments, psychosocial interventions and rehabilitation technology. As PRM is based on the principles of evidence-based medicine PRM specialist are involved in research too. Quality management programs for PRM interventions are established at national and European levels. PRM specialists are practising in various settings along a continuum of care, including acute settings, post acute and long term rehabilitation programs. The latter include community based activities and intermittent in- or out-patient programs. Within all PRM practice, Continuous Medical Education (CME) and Continuous Professional Development (CPD) are part of the comprehensive educational system.

Résumé

Le champ de compétences (CC) du spécialiste en médecine physique et réadaptation (MPR) en Europe repose sur des principes de base décrits dans le Livre blanc de MPR en Europe. Un socle consensuel du champ de compétences est le cursus établi par le Board européen pour la certification des spécialistes en MPR. Cependant, du fait de traditions nationales, des différents systèmes de santé et d’autres facteurs, l’exercice de la MPR varie suivant les régions et les pays d’Europe. Au sein d’un pays donné, la pratique professionnelle d’un médecin peut changer selon ses conditions de travail spécifique. Le but de cet article est de donner une description du CC en MPR. Les spécialistes de MPR sont concernés par une grande variété de maladies et d’incapacités. Ils interviennent dans la prévention des maladies et de leurs complications, dans le diagnostic, dans l’évaluation fonctionnelle, dans l’information et l’éducation des patients, des familles et des professionnels de santé, dans le traitement (thérapie physique, médicaments et autres interventions thérapeutiques) et dans la recherche. Les actes de MPR sont souvent organisés en programmes. Les spécialistes en MPR ont la connaissance de la conduite de la rééducation, du travail en équipe, des traitements médicaux et physiques, de la technologie au service de la rééducation, de la prévention, de la prise en charge des complications et de la méthodologie en matière de recherche dans leur domaine. Les spécialistes en MPR sont impliqués dans la réduction des conséquences fonctionnelles de nombreuses affections et s’occupent des incapacités et du fonctionnement pour chaque patient. Les aptitudes diagnostiques et d’évaluation comprennent toutes les grandes fonctions et les structures du corps, les activités, les actes de participation en rapport avec le plan de rééducation. Les activités de MPR comprennent les prescriptions médicamenteuses, les traitements physiques, les interventions psychosociales, la rééducation. La MPR est fondée sur les principes de la médecine par la preuve, le spécialiste en MPR est impliqué dans la recherche. Des programmes qualité pour les activités de MPR sont établis à un niveau national et européen. Les spécialistes en MPR travaillent dans des conditions variées à chaque étape de la filière de soins dans les établissements de soins aigus, les soins de suite et le suivi à long terme. Ce dernier secteur comprend les activités en milieu ordinaire de vie et les prises en charge en établissements de soins de longue durée, que ce soit en hospitalisation complète ou de jour. Pour toutes ces pratiques, la formation médicale continue (FMC) et l’évaluation des pratiques professionnelles (EPP) font partie intégrante du système éducatif global.

1

English version

1.1

Introduction

Physical and rehabilitation medicine (PRM) is an independent specialty, member of the Union of European Medical Specialists (Union européenne des médecins spécialistes [UEMS]) with a PRM Section and Board. The field of competence of PRM and the teaching and training programmes organized at national and European levels aim to respond to:

- •

population health needs. Improvement in acute care and life expectancy has led to an increase in the number of people with activity limitation and participation restriction;

- •

individual patient’s goals. PRM specialists set up and coordinate individual care pathways.

PRM interventions of course have to be adapted to the needs of individual patients and will be different in different phases of the diseases and functional recovery . Epidemiological studies on disabled persons within the European Union (EU) show an increased number of people with disabilities . The population prevalence amounts to 10% .

Several factors have led to increased demand:

- •

the improvement of acute care, the life expectancy lengthening thanks to the progress of public health in developed countries ;

- •

people with disabilities and user organisations are more aware of the medical and social new opportunities available to improve their quality of life;

- •

thanks to improvements in communication (patientś reviews, websites with accurate information) patients and families have greater awareness of available treatments.

Patients’ needs may differ with respect to the phases of the evolution of their pathology: acute phase, post-acute phase, steady state with sequels. Table 1 will give an overview on patients needs during acute, post acute and long-term phases as well as in prevention.

| Patients’ needs during acute phase | Diagnostic and assessment of functional loss Prevention of usual complications, these complications have to be anticipated and recognised by the PRM specialist (deconditioning and malnutrition, pressure ulcers, thromboses, joint contractures, spasticity, mood disturbances) Preservation or restoration of their main functions, capacities, participation Orientation and integration as soon as possible towards a specific PRM programme adapted to the patients and their needs and wishes Presentation and explanation of these programmes, their milestones to the patients and their families along with the referent professionals for them, for example their general practitioners, their nurses or physical therapists Adaptation of these programmes to the particularities of each patient and family Planning discharge from hospital |

| Patients needs during post acute phase within dedicated PRM facilities | Diagnostic and treatment of complications linked to the initial pathology and of complications Evaluation based on ICF, definition, presentation, coordination of the PRM programme with the expected targets, the tools and methods which will be used to assess the results, definition in collaboration with patients and their families of the treatment targets, the phases and the assessments to be set up |

| Patients needs during steady state | Assessment of long-term disabilities, activity limitations and participation restrictions as well as of rehabilitation potential Long-term follow-up of people with disabilities including adaptation of treatments to the progress or decrease of the patients functional capacity and progress of therapies and technologies Analysis of contextual factors influencing the patients’ functioning Setting-up a long-term PRM-plan Prescribing PRM-interventions including technical aids and coordination of multi-Professional team work Education of patient and relatives Supporting participation including return to work and leisure activities and social support |

| Prevention | Teaching and applying primary prevention measures such as management of risk factors (e.g., hypertension for stroke), physical activity and healthy food Teaching health promoting behaviour both in healthy people and persons with chronic conditions (e.g., lifting & handling techniques, back schools, physical training, and others) with a long-term perspective Prevention of complications after acute trauma or disease as well as in the post-acute rehabilitation phase (see above) |

This paper intends to describe the field of competence of the specialist of PRM starting from professional practice and clinical work with the patients . It is based on the definition of the field as given by the UEMS (“PRM is an independent medical specialty’ concerned with the promotion of physical and cognitive functioning, activities [including behaviour], participation [including quality of life] and modifying personal and environmental factors. It is thus responsible for the prevention, diagnosis, treatments and rehabilitation management of people with disabling medical conditions and co-morbidity across all ages”) and the descriptions made in the White Book on PRM in Europe . Additionally, it reflects the discussion about an ICF-based conceptual description of PRM .

1.1.1

Professional practice of the specialist of physical and rehabilitation medicine

As mentioned above professional practice of the specialist in PRM depends on the pathologies to be treated, the limitations in functioning of the respective person as well as on the phase of the disease, the setting he or she is working in and the personal factors of the patient (e.g., age, gender, comorbidities, coping strategies and others). It includes diagnosis and staging of the underlying pathology, the prescription and/or application of a wide range of interventions and the PRM programme management. Additional skills of the PRM specialists include PRM team cooperation, research in the field as well as quality control and management .

PRM specialists have a number of skills ( Table 2 ). Their basic medical training gives them competencies, which are enhanced by knowledge and experience acquired during their core training in other specialties (internal medicine, surgery, psychiatry, etc.). The core specialty competencies of PRM are provided during their specialist training and these are further enhanced by knowledge and experience of subspecialty work . As in other medical fields, PRM specialists have a comprehensive education as defined in the European Board Curriculum ( www.euro-prm.org ). However, during professional practice in different settings and the clinical work with patients with specific health conditions specific knowledge, skills and attitudes will be acquired by the PRM specialist (see Chapter 2 and Fig. 1 below)

| Medical assessment in determining the underlying diagnosis |

| Assessment of functional capacity and the potential for change |

| Assessment of activity and participation as well as contextual factors (personal characteristics and environment) |

| Knowledge of core rehabilitation processes and their evidence base |

| Knowledge on the competencies of all team members involved in rehabilitation programs |

| Devising a PRM intervention plan |

| Knowledge, experience and application of medical and physical treatments (including physical modalities, natural factors and others) |

| Evaluation and measurement of outcome |

| Prevention and management of complications |

| Prognostication of disease/condition and rehabilitation outcomes |

| Knowledge of rehabilitations technology (orthotics, prosthetics, technical aids and others) |

| Team dynamics and leadership skills |

| Teaching skills (patients, carer, tem members and others) |

| Knowledge of social system and legislation on disablement including educational and vocational aspects and compensation |

| Basic knowledge of economic (and financial) aspects of rehabilitation |

| Methodology of research in the field of biomedical rehabilitation sciences and engineering |

The field of competence will refer to the three main classifications of the World Health Organisation being:

- •

the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) ;

- •

the International Classification of Functioning, Disabilities and Health (ICF) and;

- •

the International Classification of Health Interventions (ICHI) .

1.1.2

Pathologies treated by the specialist of physical and rehabilitation medicine (ICD)

The classification referred to is the ICD .

Diseases in which the specialist of PRM can be involved, can be classified relating to their causal mechanism (for example, traumatic or not), to the system or organ concerned, or to the age . Examples are listed in Table 3 .

| Traumatic diseases: brain injury, spinal cord injury, multiple trauma, peripheral nervous lesions, sports trauma, trauma during long-term disabling disease, work-related trauma |

| Non traumatic diseases of the nervous system: stroke, degenerative disease (Parkinsonism, Alzheimer’s disease and others) multiple sclerosis, infection or abscess of the central nervous system, tumour of the CNS, spinal cord paralysis whatever the cause, complex consequences of neurosurgery, muscular dystrophy and neuromuscular disorders, peripheral neuropathies (among them Guillain Barre polyradiculopathy), nervous compression, congenital diseases (cerebral palsy, spina bifida, and others), metabolic or biochemic genetical diseases |

| Acute or chronic pain from various causes such as amputation, post surgical care, critical illness polyneuropathy |

| Complex status of various and multiple cause: bed rest syndrome, effort deconditioning, multisystem failure |

| Non traumatic diseases of the musculo-skeletal system: spinal column (chronic and acute low back pain, cervical or thoracic pain), infectious, degenerative and inflammatory arthropathies (mono and poly arthritis), vascular amputation, soft tissues disorder including fibromyalgia, complex disorders of the extremities (hands, feet), osteoporosis, work-related chronic pain syndrome, chronic fatigue syndrome |

| Cardiovascular diseases: ischaemic heart diseases, cardiac failure, valve diseases, lower limb atherosclerosis, myocarditis, high blood pressure, heart transplant |

| Diseases of the lymphatic system |

| Diseases of the respiratory system: asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pulmonary fibrosis, pneumoconiosis, asbestosis |

| Endocrine and metabolic diseases: diabetic complications, complications of the metabolic syndrome, obesity |

| Diseases of the genito-urinary system: chronic renal failure, vesico-sphincterian disorders, genito-sexual disorders |

| Infectious and immunologic diseases: consequences of the HIV infection, transplant of the bone marrow |

| Cancer, its treatments and their functional consequences |

| Age-related disorders |

| Other diseases in children: scoliosis, congenital malformations |

PRM specialists are mainly involved in promoting functioning and in reducing functional consequences of these conditions. They are involved in the long-term follow-up of patients with long-term conditions in the aim of preserving autonomy, social integration and quality of life.

1.1.3

Functioning and disabilities managed by the specialist of physical and rehabilitation medicine (ICF)

The management of functioning and disabilities of the Specialist in PRM is based on the comprehensive model of functioning, as described in the ICF. The classification referred to is the ICF too .

The management of functioning and disability by a specialist for PRM includes the treatment of the underlying pathology as well as the improvement of body structures and functions, activities and participation as well as to modify the contextual factors (including contextual and personal factors). These dimensions are defined as follows:

- •

a health condition is an umbrella term for disease, disorder, injury or trauma and may also include other circumstances, such as ageing, stress, congenital anomaly, or genetic predisposition. It may also include information about pathogenesis and/or aetiology. There are possible interactions with all components of functioning, body functions and structures, activity and participation;

- •

body functions are defined as the physiological functions of body systems, including mental, cognitive and psychological functions. Body structures are the anatomical parts of the body, such as organs, limbs and their components. Abnormalities of function, as well as abnormalities of structure, are referred to as impairments, which are defined as a significant deviation or loss (e.g. deformity) of structures (e.g. joints) or/and functions (e.g. reduced range of motion, muscle weakness, pain and fatigue);

- •

activity is the execution of a task or action by an individual and represents the individual perspective of functioning. Difficulties at the activity level are referred to as activity limitation (e.g. limitations in mobility such as walking, climbing steps, grasping or carrying);

- •

participation refers to the involvement of an individual in a life situation and represents the societal perspective of functioning. Problems an individual may experience in his/her involvement in life situations are denoted as participation restriction (e.g. restrictions in community life, recreation and leisure, but may be in walking too, if walking is an aspect of participation in terms of life situation);

- •

environmental factors represent the complete background of an individual’s life and living situation. Within the contextual factors, the environmental factors make up the physical, social and attitudinal environment, in which people live and conduct their lives. These factors are external to individuals and can have a positive or negative influence, i.e., they can represent a facilitator or a barrier for the individual;

- •

personal factors are the particular background of an individual’s life and living situation and comprise features that are not part of a health condition, i.e. gender, age, race, fitness, lifestyle, habits, and social background;

- •

assessing the biography of patients is useful, particularly their personal, social, vocational and recreational history. Personal goals are also important to record, e.g. what are the wishes of the patients, what is important for their quality of life?

- •

risk factors could thus be described in both personal factors (e.g. lifestyle, genetic make-up) and environmental factors (e.g. architectural barriers, living and work conditions). Risk factors are not only associated with the onset, but interact with the disabling process at each stage.

1.1.4

Diagnosis and assessment (ICHI)

The classification referred to is the ICHI .

PRM doctors recognise the need for a (or several) definitive diagnosis prior to treatment and problem-orientated PRM programme. In addition, they are concerned with aspects of functioning and participation that contribute to the full evaluation of the patient in determining the treatment goals . Diagnosis and assessment in PRM comprise all dimensions of body functions and structures, activities and participation issues relevant for the rehabilitation process . Additionally relevant contextual factors are assessed.

History taking in PRM includes analysing problems in all the ICF dimensions. In order to obtain a diagnosis of structural deficits relevant to the disease and the PRM-programme.

Standard investigations and techniques are used in addition to clinical examination. These include laboratory analysis of blood samples, imaging, etc.

Clinical evaluation and measurement of functional restrictions and functional potential with respect to the PRM-programme constitute a major part of diagnostics in PRM. These include the clinical evaluation of muscle power, range of motion, circulatory and respiratory functions.

Qualitative and quantitative assessment of body functions based on technical equipment. These measurements may include muscle testing (strength, electrical activity and others), testing of circulatory functions (blood pressure, heart frequency, EMG while resting and under strain), lung function, balance and gait, hand grip, swallowing function and others. PRM specialists use specialised technical assessments of performance such as gait and movement analysis, isokinetic muscle testing and other movement functions.

In PRM-programs of patients with certain conditions specialised diagnostic measures will be required, e.g. dysphagia evaluation in patients with stroke, urodynamic measurements in patients with spinal cord injury, or executive function analysis in patients with brain injury.

Patients’ activities can be assessed in many ways. Examples of two important methods are standardised activities of single functions performed by the patient (e.g., walking test, grip tests or handling of instruments, performance in standardised occupational settings) and assessments of more complex activities, such as the activities of daily living (washing oneself, dressing, toileting and others) and performance in day-to-day living (walking, sitting, etc.)

Numerous scales are used to assess patients’ activities in PRM assessment questionnaires

Socioeconomic parameters (e.g., days of sick leave) are used in order to evaluate social or occupational participation problems. Many assessment instruments in PRM combine parameters of body functions, activities and participation.

The relevant contextual factors with respect to the social and physical environment are evaluated by interviews or standardised ICF-based checklists. For the identification of personal factors, for example, standardised questionnaires may be used to assess coping strategies.

1.1.5

Treatments and Interventions (ICHI)

Also here the classification referred to is the International Classification of Health Interventions of the WHO (ICHI) .

PRM specialists perform and/or prescribe medical and physical interventions and provide information and education programs for patients and their families. Many of the PRM interventions listed below are performed by therapists (physiotherapists, occupational therapists, speech and language therapists, rehabilitation nurses and others) and appropriately coordinated in a multi-professional patient-centred team. Of course other professionals such as psychologists, social workers, prosthesits and others will contribute to team-integrated care.

The classification referred to is the International Classification of Health Interventions (ICHI) PRM specialists use diverse interventions. They develop an intervention plan based on the diagnosis of lesions, the evaluation of impairments, activities limitations, participation restrictions and the functional performance of the patient .

This PRM programme is explained and proposed to the patients, their families and the confident persons (e.g., relatives, friends) they wish.

As diagnosis and assessment in PRM cover a wide range of methods other team members will contribute to this process. In many cases, the task of diagnosis of the pathology falls to the PRM specialists, however, in some cases other medical specialists will be involved too (e.g., neuroradiologists for lesions of the central nervous system). The evaluation of functions and activities can be performed also by PRM specialists, however, frequently other team members, such as occupational therapists, physiotherapist, speech and language therapist will perform functional assessements. The evaluation of participation can be performed by the PRM specialists, but also other health professionals (social workers, psychologists, and others).

Family and relatives should be consulted in order to build a clearer picture of activity limitations and participation restrictions. Patients may underestimate their need for support (particularly following acquired brain injury). The estimation of dependency level is of high value in order to define the number of hours and the type of health and social, professional need by a patient. It has high economical consequences. There are several useful instruments. One straightforward validated instrument for day-to-day clinical use is the Northwick Park Dependency Scale .

Thereafter, the PRM-specialist either performs the intervention aiming at solving the given problems or other team members may do so. Alternatively or additionally the PRM specialists will prescribe the therapy that then will be performed by other therapists (e.g. Physiotherapists, Occupational Therapists, Speech and Language Therapists, and others. Practical procedures include injections and other techniques of drug administration. Assessment and review of medical interventions and prognostication are part of practice of PRM specialists too.

Interventions are shown in Table 4 .

| Medical interventions | Medication aiming at restoration or improvement of body structures and/or function, e.g. pain therapy inflammation therapy regulation of muscle tone and others improvement of cognition, improvement of physical performance treatment of depression or mood disturbances, |

| Physical therapies and physiotherapy | Manual therapy techniques for reversible stiff joints and related soft tissue dysfunctions kinesiotherapy and exercise therapy electrotherapy other physical therapies including ultrasound, heat and cold applications phototherapy (e.g. UV therapy) hydrotherapy and balneotherapy massage therapy lymph therapy (manual lymphatic drainage) acupuncture and others |

| Occupational therapy | Training of activities of daily living and occupation support of impaired body structures (e.g. splints) teaching the patient to develop skills to overcome barriers to activity of daily living adjusting work & home environments teaching strategies to circumvent cognitive impairments enhance motivation |

| Speech and language therapy within the framework of complex specialized PRM programmes Dysphagia management | |

| Neuropsychological interventions | |

| Psychological interventions, including counselling of patients and their families | |

| Nutritional therapy | |

| Disability equipment, assistive technology, prosthetics, orthotics, technical supports and aids | |

| Patients, families, professionals’ education | |

| PRM nursing |

1.1.6

PRM programmes of care management (ICF, ICHI)

The specialists in PRM plays a complex role, which starts with a medical diagnosis, a functional and social assessment and continues with the definition of the different goals to achieve, according to the patient needs, the set up of a comprehensive strategy, the achievement of personal intervention including prescription of medication, physical therapies (including physical modalities, physiotherapy, occupational therapy and other) and rehabilitation technology, and the supervision of team or network cooperation. It ends after a final assessment of the overall process.

This process can be named a PRM programme of care . It refers to all three classifications of WHO (ICD, ICF and ICIH). The UEMS accreditation of PRM programs follows the following pattern:

- •

general basis: pathological and impairment considerations, functioning and disability issues, social and economic consequences, main principles of the programmes;

- •

aims and goals: target population, goals of the programme, targets in terms of ICF;

- •

content: assessment (diagnosis, impairment, activity and participation, environmental factor), intervention (timeframe of the programme, PRM specialist’s intervention, team intervention), follow-up and outcome, discharge planning and long-term follow-up;

- •

environment and organization: clinical setting, clinical programmes, clinical approach, facility, safety and patient rights, advocacy. PRM Specialists in the programme and team management;

- •

information management: patient records, management information, programme monitoring and outcome;

- •

quality improvement: strong and weak points of the programme, action plan to improve the programme;

- •

references: scientific references and guidelines cited in the above description, details about national documents.

PRM programmes of care adapt general principles to any local need and condition. For instance, PRM early intervention in an acute care hospital will comprise a different programe of interventions for brain-injured people from that of a community-based unit dealing with people suffering from brain damage. A Posture and Movement Assessment Unit will provide a third kind of additional assessment and advisory program. In big cities, specialised PRM programmes may accept referrals from a large catchment area and address the needs of a very specific population. Other programmes will be designed to respond to more common health conditions with less technology and specialized resources but with a more personal relationship.

PRM programmes of care should address one special issue, rather than describe the overall activity of a PRM Department. The main entrance to the programme may be:

- •

an impairment (pathology): spinal cord injury, knee ligament reconstruction, stroke, low back pain;

- •

an activity and participation limitation: walking disability, aphasia;

- •

a vocational goal: independent living for brain-injured people, professional activities for people with chronic low back pain;

- •

a period of life, with some specific features: children with cerebral palsies, sportsmen/women with musculoskeletal injuries, manual workers with low back pain, elderly people with falling hazards.

PRM programmes of care are the basis for a quality approach. This issue will be further developed below in Chapter 1.6 .

1.1.7

Quality control and management (ICHI)

Achieving the best quality of care as possible is an ethical obligation for any physician. However, beyond the personal commitment, some pioneers have started to express the quality approach in a more formal way, e.g. the Mayo brothers, whose precepts remain up to date.

On the legal ground, the Council of Europe issued in 1997 the Recommendation No R(97)17 about the development and implementation of quality improvement systems (QIS) in health care. The UEMS started to address this issue very early and adopted, as soon as 1996 a first European Charter on Quality Insurance in Specialized Medical Practice.

In European countries, certification and accreditation mandatory procedures are focused either on physicians or on facilities. In France, accreditation of facilities contains some special features adapted to post-acute settings (Services de suite et de réadaptation [SSR]), but the recent merging of the different kinds of settings into a single ensemble has led to confusion, so this cannot be given as an example for PRM projects.

However, the French PRM organizations (SYFMER, SOFMER, FEDMER) have issued a series of papers addressing the organizational aspects of PRM Practice:

- •

charter on Quality in PRM (1997);

- •

recommendations for the equipment of outpatient PRM facilities (2002);

- •

inclusion criteria of patients into PRM facilities (2008).

In this perspective, the concept of PRM Programme of Care (PRM-PC), has quickly emerged as the best basis for developing a European approach of Quality of Care. The PRM Specialist, who is the responsible person for a PRM-PC, has to describe his/her programmes with respect to the definition given in chapter E.

On this basis, a European Accreditation of PRM-PC has been set up on the web-site www.euro-prm.org . The main criteria for acceptance are:

- •

the responsible person of the programme is PRM Board certificated doctor;

- •

the programme is clearly structured and described;

- •

the programme demonstrates evidence of using the ICF concept;

- •

quantified data about the target population are given, goals must be consistent and should be expressed in terms of ICF categories;

- •

environment and organization of the programme is clearly defined, PRM Specialists participating in the programme should be listed, staff competencies should be adequate, adequate continuing vocational training for physicians and staff must be organized;

- •

clear definitions of admission and discharge criteria should be given, the programme should include properly organized patient records;

- •

the references are cited within the description of the programme, there should be evidence that the references cited are relevant and incorporated into PRM practice.

The criteria for refusal are:

- •

the Programme of Care submitted is not run by a PRM Board Certified Specialist;

- •

or there is a combination of the following negative aspects:

- •

no provision is made for vocational training on the PRM health care programme;

- •

no follow-up is being carried out on the outcomes of the programme;

- •

the scientific bases of the programme have not been specified.

Operating PRM program quality management doesn’t require an extensive assessment of numerous parameters, which may become incompatible with a normal daily practice. Here, it is useful to make a difference between a Clinical Research Programme and the Assessment of a PRM-PC. Whereas the general goal of clinical research is to give the most definite answer to a simple and concise question, a programme of care, aims at performing an efficient intervention onto the widest population as possible, only defined by the same issues to deal with, the same goal to reach and a potential compliance to the scheduled intervention. For instance, a follow-up programme of patients after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction can also be applied, subject to some special adaptations, to reconstruction of the posterior cruciate ligament or to complex knee damage. Of course, it will be necessary to adjust the goals and the calendar, to detail precautions and specific measures to take for each sub-group.

Routine assessment in daily clinical practice can address a limited number of parameters only, which should be chosen as significant indicators of the progress or the difficulties of the patient and on the programme efficiency. Working within team cooperation may help to share the tasks, especially those related with more or less sophisticated and time consuming tests. Nevertheless, the cost of this operation has to be considered and maintained under a reasonable level, without prejudice for the concrete care of the patient.

The choice of criteria and methods of assessments therefore results from a compromise between the assessments goals and the available means. This choice may move with time where some parameters appear to be redundant, always get the same score at the same stage of the programme or prove to have no practical significance, whereas other parameters can reveal a dysfunction or a good enough level of performance to allow the starting of the next programme stage. All these concerns should be expressed within the care programme description.

1.1.8

Team work

Effective team working plays a crucial role in PRM. As part of its role of optimizing and harmonizing clinical practice across Europe, the Professional Practice Committee of UEMS, PRM Section has reviewed patterns of team working and debated recommendations for good practice .

Effective team working produces better patient outcomes (including better survival rates) in a range of disorders, notably following stroke (for an overview see 26). There is limited published evidence concerning what constitute the key components of successful teams in PRM programmes. However, the theoretical basis for good team-working has been well-described in other settings and includes agreed aims, agreement and understanding on how best to achieve these, a multi-professional team with an appropriate range of knowledge and skills, mutual trust and respect, willingness to share knowledge and expertise and to speak openly. A central element of this are regular team meetings.

PRM specialists have an essential role to play in interdisciplinary teams; their training and specific expertise enables them to diagnose and assess severity of health problems, a prerequisite for safe intervention as well as taking team leadership. Their broad training also means they are able to take holistic view of an individual patient’s care, and are therefore well-placed to coordinate PRM programmes and develop and evaluate new management strategies.

Additionally to multi-professional teamwork networking out of PRM facilities from acute care to long term facilities or community-based services is crucial to PRM practice. This includes communication and counselling with other specialists for the underlying pathology, with the general practitioner (especially in long term PRM-programs) as well as to social network including social services and employers. PRM provides continuous education of the patient, his or her family and the PRM team. Of course, the exchange of information must follow the strict data-protection rules and must be agreed by the patient.

PRM have to know the competencies of the professionals involved in the PRM team. When they create these teams they have to know the professionals with whom they will to cooperate best. This is dependent on the patients they welcome to the PRM facilities they coordinate, the stage of the evolution of these patients. PRM specialists have to take lead of the team. This includes asking the team members relevant questions to be answered in a comprehensive way.

PRM specialists have links with the acute facilities wishing to send patients. They have to define the criteria for admission defining the medical and social profile of the patients they admit. PRM specialists have links with long-term facilities (either PRM coordinated or not) and ambulatory facilities (either PRM coordinated or not). The criterion for discharge to long term facilities or to return to home, without or with a support such a medical and social service (PRM run or not) have to be defined. PRM specialists have to develop out of the PRM facilities they coordinate, a network of persons, mainly health and social Professional but also public or private organizations which can facilitate integration, avoid or solve problems encountered by patients (e.g. TBI with mood disturbance) and maintain health.

1.2

Education and training

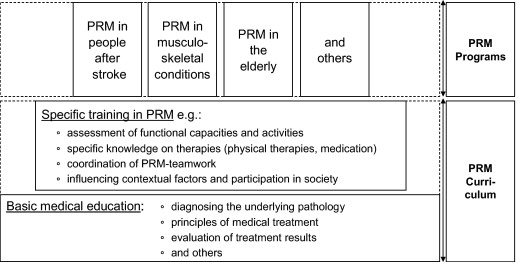

PRM is part of undergraduate and specialist training in Europe . Undergraduate training aims at basic knowledge in the social and medical model of disability, the ICF-model as well as indications and contraindications of PRM-interventions and programs . Specialist education consists of basic medical education and specific training in PRM methodology ( Fig. 1 ). Additional knowledge and aptitudes are required for specific groups or patients (e.g., those with disorders of the nervous, locomotor or cardiovascular system) or settings (acute hospital, PRM centre, out-patient or community-based service; for an overview see ). Within this phase, as in all PRM practice, Continuous Medical Education (CME) and Continuous Professional Development (CPD) are part of the comprehensive educational system .

1.2.1

Undergraduate education in the field

As any patient may require rehabilitation and physical therapies, all physicians need to achieve basic knowledge of PRM. A motion has been agreed by the UEMS Council that undergraduate education in all the EU Medical Schools should include a teaching programme on disability issues . Models have been developed to systematically include PRM in undergraduate teaching programmes .

1.3

Post graduate education

PRM is an independent speciality in all European countries except Denmark and Malta, but its name and focus varies somewhat according to different national traditions and laws. Training usually lasts for between four and six years depending on the country. The content of training varies from country to country, however, in majority training programmes include rotation within PRM-departments with different main areas as well as other related fields (e.g., internal medicine, neurology, orthopaedic surgery). The European Board of PRM has developed a comprehensive system of postgraduate education for PRM specialists . This consists of:

- •

a curriculum for postgraduate education containing basic knowledge and the application of PRM in specific health conditions;

- •

a standardised training course of at least four years in PRM departments and registered in detail in a uniform official logbook;

- •

a single written annual examination throughout Europe;

- •

a system of national managers for training and accreditation to foster good contacts with trainees in their country;

- •

standard rules for the accreditation of trainers and a process of certification;

- •

quality control of training sites performed by site visits of accredited specialists;

Further information on the regulations of this education and training system are available on the Section’s website ( www.euro-prm.org ) where application forms are also available (see also www.cofemer.fr ).

1.3.1

Continuous medical education, continuous professional development

CME and CPD are an integral part of medical specialists’ professional practice and PRM specialists need (either on a mandatory or ethical basis) to demonstrate their continued competence like all other doctors. CPD covers all aspects of updating medical practitioners, of which CME is one component. The PRM specialty has set up various congresses, teaching and training programmes across Europe, which serve to educate PRM specialists and their colleagues in PRM teams. These cover basic science and clinical teaching topics, as well as investigational, technical and management programmes .

At EU level the accreditation of PRM congresses is under supervision of the UEMS European Accreditation Council of CME (EACCME). The UEMS PRM Board on the basis of an agreement signed with the EACCME is the referent body to evaluate the quality of PRM congresses.

A CME and CPD program is organised on European level for accreditation of international PRM congresses and events. The programme is based on the provisions of the mutual agreement signed between the UEMS European Accreditation Council of CME (EACCME) and the UEMS-PRM Section and Board. The European provisions are the same for all specialities. The PRM Board has created the CPD/CME Committee, which is responsible for the relevant continuing programs within our speciality, for the accreditation of the several scientific events on European level and the scientific status of the Board Certified PRM specialists.

EACCME is responsible for coordinating this activity for all medical specialties and the UEMS website gives details of the CME requirements for all specialists in Europe ( www.uems.org ). Each Board-recognised PRM specialist is required to gain 250 educational credits over a five-year period for the purposes of reaccreditation ( www.euro-prm.org ). Medical doctors are required to fulfil their CME requirements before they can be accreditated and this is becoming an essential part of national as well as European life. Obligatory CPD/CME is established in certain countries of Europe and is becoming increasingly required in medical practice.

1.4

Research

PRM is based on the principles of evidence-based medicine and research in PRM has made great progress during the last two decades . Whereas the physiological mechanisms of action of physical modalities of function have traditionally been central to scientific interest during the last 15 years, an increasing number of prospective trials have been performed, in which the clinical efficacy of PRM in many diseases, such as low back pain, stroke, brain and spinal cord injuries, rheumatoid arthritis, cardiovascular, pulmonary and metabolic disorders, has been tested. For many conditions, meta-analyses of controlled trials are already available, but future research should focus on improving methodological and scientific rigour of clinical trials, and use of standardised outcome measures , so that results can be pooled for statistical analysis . Other types of synthesis, which start off with a broad question that may lead to a more creative synthesis of the findings of a number of studies, might benefit from improvements that can be borrowed from the systematic review tradition. Although they all might address the questions the authors set out to answer, more explicit information as to how relevant information was collected (a “search strategy”) and how judgments were made as to the nature (content) and quality (methodology) of the studies would help the audience to evaluate what a review offers them .

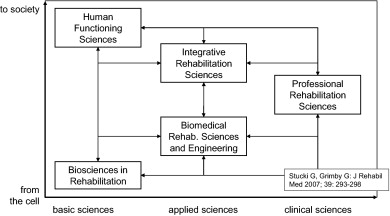

Research in PRM requires a comprehensive perspective to such diverse areas as the natural and engineering sciences, the rehabilitation professions, the behavioural sciences and psychology, and the social sciences and a wide range of related scientific fields ( Fig. 2 ). At a European level a systematic structure to present the results of PRM research has been developed , and a network of scientific journals has been established

Research in PRM is necessary to understand the basic processes of PRM such as how individuals acquire new skills, and how the tissues of the body (for example, the muscles, or neuronal pathways in the central nervous system) can recover from or adapt to the effects of trauma or disease. Basic sciences are needed to describe, understand and explain phenomena, far from empirical descriptions.

Research can also delineate the incidence and prevalence of disabilities, and identify the determinants both of recovery and of the capacity to change, to acquire new skills, and to respond to PRM programmes. Integrative rehabilitation sciences focus on performance defined as what a person does in real world. We need also to enhance our understanding of the spontaneous evolution of health conditions and their impact on patients without the benefit from a PRM programme.

New technologies emerge and should be adapted for use by people with disabilities. Assistive technology is one of the most important and promising research fields today and in the future. Tissue engineering, interactive systems, biomechanics, nanotechnology and other innovative technologies are contributing to this field. The costs of health care including PRM services will increase and politicians will force health care providers to restrict their expenses and to show that they organize this care efficiently. PRM is a partner in the discussion with patients, politicians, ministries of health and insurance companies, as it has the capacity to base its arguments on sound evidence in the public arena, which only research can provide.

Research in PRM does not only need standard approaches to basic science and medical practice research interventions. Progress in methodology has been considerable. Therefore, randomised controlled studies are possible in many areas, but are less effective when the objectives sought and worked for in a group of subjects differ between individuals, especially when this occurs for personal or social rather than for biological reasons. The clinical trial designs that have been developed in the field of clinical psychology, behavioural sciences and social sciences are often more fruitful and scientifically appropriate than designs developed for the assessment of drug effects . A combination of qualitative and quantitative methods often provides a scientifically sounder analysis of effectiveness in rehabilitation. Interdisciplinary collaborations can combine biomedical and engineering approaches with approaches developed by behavioural and social sciences, and thus facilitate effective practice and programs to address patients and career’s needs.

Additionally research on evidence of the cost-effectiveness of PRM-interventions is needed because a wide range of different techniques has to be available to the treating team in order to meet the differing needs of individuals in any group of patients.

1.5

Future tasks in defining the field of competence in different sectors of the health care system and special groups of patients

The above given definitions and descriptions are a starting point for further discussions and a consensus finding process at a European and international level . Based on this the tasks and field of competence of the PRM specialist in the different clinical settings and in PRM programs for special groups of patients will be described more in detail . Examples for this are:

- •

the role of PRM in Acute Rehab Units (ARU) and peripatetic Acute Rehab Teams (ART);

- •

the role of PRM in rehab teams (and access to therapists);

- •

the role of PRM in integrative care concepts;

- •

the cooperation with other medical specialties, other health, social, law, economical and technical professionals in categories of patients such as Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) and others;

- •

the role of PRM in community based rehabilitation and;

- •

the contribution of PRM in rehabilitation of children and of elderly people and;

- •

the role of PRM in rehabilitation of defined medical conditions.

For the gathering of information and discussion a series of special sessions will be implemented in National and European congresses within the field. The process of consensus will be open to all European specialists interested and coordinated by the UEMS-PRM-section. Continuous information will be provided on the website of the Section: www.euro-prm.org .

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest concerning this article.

2

Version française

2.1

Introduction

La médecine physique et réadaptation (MPR) est une spécialité médicale indépendante membre de l’Union européenne des médecins spécialistes (UEMS) avec une section et un board de MPR. Le champ de compétences (CC) de la MPR et les programmes éducatifs organisés à un niveau national et européen ont pour but de répondre :

- •

aux besoins de la population. L’amélioration des soins aigus et de l’espérance de vie ont conduit à une augmentation du nombre de personnes ayant des incapacités et des limitations de participation ;

- •

aux objectifs individuels des patients, en fonction desquels les spécialistes en MPR élaborent et coordonnent des parcours de soins individualisés.

Les actes de MPR doivent bien sûr être adaptés aux besoins de chaque patient et ne seront pas les mêmes en fonction des stades des maladies et du niveau de récupération fonctionnelle des patients . Les études épidémiologiques sur les personnes handicapées au sein de l’Union européenne (UE) montrent un nombre croissant des personnes présentant des incapacités . La prévalence dans la population européenne atteint les 10 % . Plusieurs facteurs ont conduit à cet accroissement de la demande:

- •

l’amélioration des soins aigus, l’amélioration de l’espérance de vie grace aux progrès de santé publique des pays développés ;

- •

grâce à l’amélioration de la communication (journaux d’associations, site web avec des informations pertinentes), les patients, leurs familles et les organisations d’usagers sont mieux informés des possibilités médicales et sociales pour améliorer leur qualité de vie.

Les besoins des patients peuvent être différents selon les stades d’évolution de leur maladie: phase aiguë, phase subaiguë, état stable avec séquelles. Le Tableau 1 rappelle les besoins des patients durant les différentes phases de la maladie et les stades de la prévention.

| Besoins des patients à la phase aiguë | Diagnostic et évaluation de la perte fonctionnelle Prévention des complications habituelles, ces complications doivent être anticipées et diagnostiquées par le spécialiste en MPR (déconditionnement, malnutrition, escarres, thrombose, diminution de la mobilité articulaire, spasticité, troubles de l’humeur) Conservation ou restauration des principales fonctions, capacités et participation Orientation et intégration dès que possible vers des programmes spécifiques de MPR adaptés aux besoins et aux souhaits des patients Présentation et explication de ces programmes de leurs étapes au patient et à sa famille, ainsi qu’aux professionnels impliqués, par exemple leur médecin généraliste, leur infirmière ou leur kinésithérapeute Adaptation de ces programmes aux particularités de chaque patient et de chaque famille Organisation de la sortie de l’hôpital |

| Besoins des patients durant la phase subaiguë au sein de structures dédiées à la MPR | D iagnostic et traitement des complications liées à la pathologie initiale et des complications secondaires Évaluation basée sur la CIF Définition, présentation, coordination du programme de MPR avec les objectifs attendus, les moyens et les méthodes qui seront utilisés pour évaluer les résultats Définition en collaboration avec le patient et la famille des objectifs du traitement, de ses étapes et des évaluations à organiser |

| Besoins des patients durant la phase chronique | Évaluation des incapacités durables, des limitations d’activités, des restrictions de participation ainsi que des possibilités de rééducation Suivi au long cours de personnes avec des incapacités, dont l’adaptation des traitements aux progrès ou à la diminution des capacités fonctionnelles des patients et des progrès thérapeutiques et technologiques Analyse des facteurs contextuels influençant le cours de la vie du patient Établissement d’un plan de MPR à long terme Prescription d’interventions de MPR incluant des aides techniques et un travail coordonné interdisciplinaire, Éducation du patient et de son entourage Aide à la participation dont le retour au travail, les activités de loisirs et les aides sociales |

| Prévention | Enseignement et application de mesures de prévention primaire comme la gestion des facteurs de risque (par exemple l’hypertension dans l’AVC), les activités physiques et l’alimentation saine Enseignement d’un comportement favorable à la santé, à la fois chez les personnes saines et chez les personnes présentant une maladie chronique (par exemple, conseils ergonomiques, école du dos, activités physiques adaptées et autres) avec une perspective à long terme Prévention des complications après un traumatisme ou une maladie aiguë mais aussi à la phase de rééducation subaiguë (voir ci-dessus) |

Cet article a pour but de décrire le CC des spécialistes en MPR à partir de l’exercice professionnel et du travail clinique avec le patient . Il est fondé sur la définition donnée par l’UEMS (« la MPR est une spécialité indépendante impliquée dans la promotion du fonctionnement physique et cognitif, des activités [y compris le comportement] et de la participation [y compris la qualité de vie]. Elle intervient sur les facteurs personnels et environnementaux. Elle est responsable de la prévention, du diagnostic, du traitement et de l’organisation de la réadaptation des personnes présentant une affection médicale invalidante et des comorbidités, quel que soit leur âge »). Le CC est également fondé sur la description faite de la spécialité, dans le Libre Blanc de MPR en Europe . Le CC est décrit en grande partie à partir du concept de l’ICF .

2.1.1

Exercice professionnel du spécialiste de médecine physique et réadaptation

L’exercice professionnel du spécialiste en MPR dépend des pathologies à traiter, de leurs stades évolutifs, des incapacités et des limitations de participation de la personne ainsi que de son lieu de vie, de ses conditions de travail, de facteurs individuels tels que l’âge, le sexe, les comorbidités, la façon dont la personne fait face à la maladie. L’exercice professionnel comprend le diagnostic, l’évaluation de la sévérité de la pathologie sous-jacente, la prescription ou la réalisation personnelle d’un grand nombre d’actes et la direction d’un programme de MPR, ce qui implique la coopération avec l’équipe de MPR, le contrôle de la qualité des soins et la recherche dans ce domaine.

Les spécialistes en MPR ont de nombreuses capacités d’intervention ( Tableau 2 ). Leur formation médicale de base leur donne des compétences qui sont améliorées par les connaissances et l’expérience acquise durant leurs stages dans d’autres spécialités (médecine interne, chirurgie, psychiatrie, etc.). Ces compétences dans des spécialités ciblées dans le cadre de la MPR sont acquises pendant la formation mais sont plus tard renforcées dans le cadre d’une sur-spécialisation . Comme dans les autres domaines médicaux, les spécialistes en MPR ont une formation globale définie dans l’ European Board Curriculum ( www.euro-prm.org ). Cependant, pendant leur exercice professionnel, dans différentes conditions et pendant leur travail clinique avec les patients présentant des problèmes de santé particuliers, des connaissances spécifiques, des compétences et des comportements seront acquis par le spécialiste en MPR (cf. Chapitre 2 et Fig. 1 ci-dessous).