Neck pain should not, and must not, be confused with cervical radicular pain. Equating the two conditions, or confusing them, results in misdiagnosis, inappropriate investigations, and inappropriate treatment that is destined to fail. So critical is the difference that pedagogically it is unwise to include the two topics in the same book, let alone the same article. However, traditions and expectations are hard to break. In deference to habit, this article addresses both entities, but does so by underplaying cervical radicular pain so as to retain the emphasis on neck pain.

In preparation for considering the pathophysiology of neck pain, a critical distinction must be made. The neck is not the upper limb. The upper limb is not the neck. By the same token, pain in the neck is not pain in the upper limb, and vice versa.

For these reasons, neck pain should not, and must not, be confused with cervical radicular pain. Neck pain is perceived in the neck, and its causes, mechanisms, investigation, and treatment are different from those of cervical radicular pain. Reciprocally, cervical radicular pain is perceived in the upper limb, and its causes, mechanisms, investigation, and treatment are different from those of neck pain. Equating the 2 conditions, or confusing them, results in misdiagnosis, inappropriate investigations, and inappropriate treatment that is destined to fail.

Confusion arises because neck pain and cervical radicular pain are both caused by disorders of the cervical spine, but this common site of disease does not constitute a basis for equating the 2 conditions. In all other respects the 2 conditions are totally different.

So critical is the difference that pedagogically it is unwise to include the 2 topics in the same book, let alone the same article. Doing so, as has been the tradition, risks readers remaining confused, and applying to neck pain the interpretations, investigations, and treatment that apply to radicular pain. However, traditions and expectations are difficult to break. In deference to habit, this article addresses both entities, but does so by underplaying cervical radicular pain so as to retain the emphasis on neck pain. Cervical radicular pain is covered in a later article, and more comprehensively elsewhere.

Radicular pain

Perhaps surprisingly, but nonetheless veritably, little is known about the causes and mechanisms of cervical radicular pain. In the literature, cervical radicular pain has conventionally been addressed in the context of cervical radiculopathy; but radiculopathy is not synonymous with radicular pain.

Cervical radiculopathy is a neurologic condition characterized by objective signs of loss of neurologic function: some combination of sensory loss, motor loss, or impaired reflexes, in a segmental distribution. None of these features constitutes pain.

Many causes of cervical radiculopathy have been reported ( Table 1 ). They share the common feature that they compress or otherwise compromise a cervical spinal nerve or its roots. The axons of these nerves are either compressed directly or are rendered ischemic by compression of their blood supply. Symptoms of sensory or motor loss arise as a result of block of conduction along the affected axons. The features of cervical radiculopathy, therefore, are essentially negative in nature; they reflect loss of function. In contrast, pain is a positive feature, not caused by loss of nerve function.

| Structure | Condition |

|---|---|

| Intervertebral disc | Protrusion Herniation Osteophytes |

| Zygapophysial joint | Osteophytes Ganglion Tumor Rheumatoid arthritis Gout Ankylosing spondylitis Fracture |

| Vertebral body | Tumor Paget’s disease Fracture Osteomyelitis Hydatid Hyperparathyroidism |

| Meninges | Cysts Meningioma Dermoid cyst Epidermoid cyst Epidural abscess Epidural hematoma |

| Blood vessels | Angioma Arteritis |

| Nerve sheath | Neurofibroma Schwannoma |

| Nerve | Neuroblastoma Ganglioneuroma |

For this reason cervical radicular pain cannot be summarily attributed to the same causes as those of radiculopathy. Compression of axons does not elicit pain. If compression is to be invoked as a mechanism for pain it must explicitly relate to compression of a dorsal root ganglion.

Laboratory experiments on lumbar nerve roots have shown that mechanical compression of nerve roots does not elicit activity in nociceptive afferent fibers. Therefore, compression of nerve roots cannot be held to be the mechanism of radicular pain. However, compression of a dorsal root ganglion does evoke sustained activity in afferent fibers; but that activity occurs in Aβ fibers as well as C fibers. Therefore, the activity is something more than simply nociceptive. This finding underlies and underscores the particular nature of radicular pain. It is shooting, stabbing, or electric in nature, traveling distally into the affected limb, which is consistent with a massive discharge from multiple affected axons. It is commonly associated with paresthesiae; which is consistent with Aβ fibers being included in the discharge.

As opposed to compression, there are growing contentions that cervical radicular pain may be caused by inflammation of the cervical nerve roots. This mechanism might be applicable to radicular pain caused by disc protrusions, because inflammatory exudates have now been isolated from cervical disc material. However, inflammation cannot be invoked as the mechanism of radicular pain caused by noninflammatory lesions such as tumors, cysts, and osteophytes. For these conditions, compression of the dorsal root ganglion is the only mechanism for which there is experimental evidence.

However, none of these considerations bear on the causes and mechanisms of neck pain. Whatever its cause, and whatever its mechanism, cervical radicular pain is perceived in the upper limb. This characteristic has been clearly shown in experiments in which cervical spinal nerves have been deliberately provoked with needles. The subjects report pain spreading throughout the length of the upper limb. But unlike the sensory loss of cervical radiculopathy, the pattern of cervical radicular pain is not dermatomal. Radicular pain is perceived deeply, through the shoulder girdle and into the upper limb proper. Radicular pain from C5 tends to remain in the arm, but pain from C6, C7, and C8 extends into the forearm and hand. These patterns of distribution indicate that the pain is not restricted to cutaneous afferents. It involves afferents from deep tissues as well, such as muscles and joints. Because the segmental innervation of deep tissues is not the same as that of skin, radicular pain cannot be, and is not, dermatomal in distribution. In particular, muscles of the shoulder girdle are innervated by C6 and C7, well away from the dermatomes of these nerves. If anything, the segmental innervation of muscles is a better guide to the distribution of radicular pain than are the dermatomes. Dermatomes are nonetheless relevant for the distribution of the neurologic signs of radiculopathy, but this has nothing to do with the distribution of pain.

Neck pain

By definition, neck pain is pain perceived as arising in a region bounded superiorly by the superior nuchal line, laterally by the lateral margins of the neck, and inferiorly by an imaginary transverse line through the T1 spinous process. This definition does not presuppose, nor does it imply, that the cause of pain lies within this area. It defines neck pain simply by where the patient feels the pain. An objective of clinical practice is to determine exactly the source and cause of this pain, and then to implement measures to stop it.

Sources of Neck Pain

The notion of source of pain is different from that of the cause of pain. A source is defined in anatomic terms, and pertains to the site from which nociception is generated, without reference to its actual cause.

Potential sources

For a structure to be a potential source of pain it must be innervated. In this regard, there is abundant information concerning the cervical spine.

The posterior neck muscles and the cervical zygapophysial joints are innervated by the cervical dorsal rami. The lateral atlantoaxial joint is innervated by the C2 ventral ramus, and the atlantooccipital joint is supplied by the C1 ventral ramus. The median atlantoaxial joint and its ligaments are supplied by the sinuvertebral nerves of C1, C2, and C3. These nerves also supply the dura mater of the cervical spinal cord. The innervation of the prevertebral and lateral muscles of the neck has not been studied in modern times, but textbooks of anatomy affirm that these are supplied by branches of the cervical ventral rami.

The cervical intervertebral discs receive an innervation from multiple sources. Posteriorly, they receive branches from a posterior vertebral plexus that lies on the floor of the vertebral canal, and which is formed by the cervical sinuvertebral nerves. Anteriorly, they receive branches from an anterior vertebral plexus that is formed by the cervical sympathetic trunks. Laterally, they receive branches from the vertebral nerve.

The vertebral nerve is formed by branches of the cervical gray rami communicantes, and accompanies the vertebral artery. In addition to giving rise to the sinuvertebral nerves, the vertebral nerve provides a somatic (sensory) innervation to the vertebral artery.

On the grounds that they are innervated, all of the muscles, synovial joints, and intervertebral discs of the neck are potential sources of neck pain, along with the cervical dura mater and the vertebral artery. However, innervation is insufficient grounds alone to credit that these structures are sources of neck pain. For a structure to be credited as a potential source, physiologic evidence of its potential is required.

In that regard, sources of neck pain have been studied in 2 ways. In normal volunteers, various structures have been studied experimentally to determine if possibly they can, and therefore could, produce neck pain. In patients suffering from neck pain, the same sites have been anesthetized to determine if doing so relieves the pain.

Normal volunteers

Classic experiments involved the noxious stimulation of posterior midline structures with injections of hypertonic saline. These experiments showed that such stimulation produces not only local neck pain but also somatic referred pain. The distribution of referred pain related to the segment stimulated. Accordingly, stimulation of upper cervical segments produced referred pain into the head; stimulation of lower cervical segments produced referred pain into the shoulder girdle and upper limb.

These experiments were important because they showed the phenomenon of somatic referred pain. They showed that disorders of the cervical spine could produce headache, as well as pain in the upper limb. In both instances the mechanism did not involve irritation of nerve roots. The mechanism involves convergence. Nociceptive afferents from the cervical spine converge with afferents from distal sites, on second-order neurons in the spinal cord. Under these conditions, spinal pain can be perceived as also arising from those distal sites.

It has been shown that noxious stimulation of the cervical zygapophysial joints causes neck pain and referred pain. The observations have been corroborated using a variety of stimuli. One series of experiments used a mechanical stimulus, in the form of an injection of contrast medium, to distend the target joint. Another used the same mechanical stimulus but also used electrical stimulation of the nerves that innervated the target joint. Both approaches found the same outcomes.

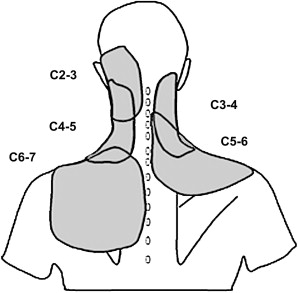

Pain from the cervical zygapophysial joints tends to follow relatively constant and recognizable patterns ( Fig. 1 ). From the C2-3 level it is referred rostrally to the head. From C3-4 and C4-5 it is located over the posterior neck. From C5-6 it spreads over the supraspinous fossa of the scapula. From C6-7 it spreads further caudally over the scapula.

Essentially similar patterns of pain have been produced by mechanical stimulation of cervical intervertebral discs. This fact underscores the rule that it is not the structure that determines the pattern of pain stemming from it, but its nerve supply. Thus, any structure innervated by the same cervical segmental nerves has the same distribution of pain. This observation means that, clinically, discogenic pain cannot be distinguished from zygapophysial joint pain, but the distribution of pain serves as a reasonable guide to the most likely segmental location of its source.

In principle, this rule would also apply to neck muscles. Pain from muscles innervated by a particular segment should be perceived in the same location as pain from articular structures innervated by the same segment. However, there have been no systematic studies of neck pain from muscles in normal volunteers. The only study involving neck muscles showed that stimulation of upper cervical muscles could produce pain in the head.

Other structures that have been shown to be able to produce neck pain and headache in normal volunteers are the atlantooccipital and the lateral atlantoaxial joints. Pain from these structures does not occur in a unique distribution. Along with the C2-3 joints, these structures all produce pain in the suboccipital region.

Clinical studies

As a complement to the studies in normal volunteers, clinical studies have provided evidence of the sources of pain in patients with neck pain. They involved either the anaesthetization or the provocation of pain.

Several studies have shown that anesthetizing the cervical zygapophysial joints can relieve neck pain. The most powerful of these used controlled, diagnostic blocks: either comparative local anesthetic blocks, or placebo-controlled blocks, each on a double-blind basis.

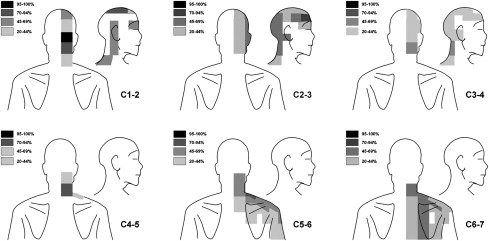

One such study examined the distribution of pain that was relieved by controlled diagnostic blocks of the zygapophysial joints at various segments, or of the lateral atlantoaxial joint. It found that, although patients conformed in general terms to the pain maps developed in normal volunteers (see Fig. 1 ), they differed greatly with respect to the patterns of distribution. Whereas some patients might suffer narrow areas of pain, others might suffer wider areas; and whereas some patients might suffer pain in longer (ie, taller) distributions, in others the distribution might be shorter. Consequently, no single pattern of distribution was characteristic of pain from a given segment, but certain rules emerged ( Fig. 2 ).

Pain from C1-2 and pain from C2-3 are similar in distribution. Both tend to center over the suboccipital region and radiate, to various extents, to the occiput, auricular region, vertex of the head, forehead, and orbit. In the head, pain from C1-2 tends to occur higher than pain from C2-3, in the vertex rather than in the forehead and temple.

Pain from C3-4 resembles that from C2-3 but tends to radiate more caudally into the neck. Pain from C4-5 tends to nestle into the angle between the lower end of the neck and the top of the shoulder girdle.

Pain from C5-6 and from C6-7 both encompass the lower neck and the shoulder girdle. Pain from C5-6 tends to radiate more laterally, over the deltoid region and into the arm. Pain from C6-7 tends to radiate more medially, over the medial scapula.

Other studies have used provocation discography to implicate the cervical intervertebral discs as sources of neck pain. However, discography is a capricious test. Even if performed carefully, with attention to testing control levels, it can be subject to false-positive responses. Moreover, in patients with neck pain, it is uncommon to find a single disc that seems to be painful. If all cervical discs are tested, 2, 3, or more can be found to be painful. Under those conditions, it is difficult to determine whether various discs are truly multiple, simultaneous sources of neck pain or whether the patient is simply expressing hyperalgesia. Nevertheless, the clinical data are consistent with observations in normal volunteers that the cervical discs are possible sources of neck pain.

Several studies have reported that the C2-3 zygapophysial joint can be the source of pain in many patients with headache. Anesthetizing the joint completely abolishes the headache in these patients. Other studies have reported the same results after anesthetization of the lateral atlantoaxial joints.

Other tissues, such as the posterior neck muscles, the cervical dura mater, the median atlantoaxial joint and its ligaments, and the vertebral artery are potential sources of neck pain, because they are all innervated, but they have not been subjected to study either in normal volunteers or in patients. That they could be sources of pain is a credible proposition, but formal evidence is lacking.

Implications

The experimental data, from normal volunteers and from patients, indicate the synovial joints and intervertebral discs of the neck are potential sources of neck pain. Other tissues such as muscles, ligaments, the dura mater, and the vertebral artery, are in theory potential sources of pain. For a structure to be promoted from a potential to an actual source of pain, it needs to be affected by a disorder capable of causing pain.

Causes of Neck Pain

Hearsay and imaging have been the traditional basis for listing causes of neck pain. Particular conditions have been regarded as a cause of neck pain simply because someone once said they were, or because they can be seen on a radiograph. Both are weak arguments subject to large errors.

Hearsay allows any conjecture to be raised as a possible cause of neck pain, but when these are listed in textbooks they tend to assume an undeserved status of veracity. Once a condition is listed, consumers tend to accept that it is a possible cause of neck pain, and proponents are excused the responsibility of providing corroborating evidence.

The necessary evidence is some objective test that confirms the presence of the condition, and which can be used to show both that the condition occurs in patients with neck pain and that it does not occur in patients without neck pain. For some conditions, the objective test may be a radiograph, but other conditions are not visible on radiographs. For these latter conditions some other from of evidence is required.

It transpires that for most entities, an objective test is not available or has not been applied. Consequently, there is no evidence that these conditions cause neck pain; they are no more than conjectures. In some instances, applying objective tests has resulted in certain, sometimes hallowed, entities being refuted as causes of neck pain.

Typical of lists of purported causes of neck pain are those published in leading textbooks of rheumatology ( Table 2 ). The lists are not identical, but there is considerable agreement about several conditions.

| Causes | Nakano | Hardin and Halla | Binder |

|---|---|---|---|

| Serious but Rare | |||

| Vertebral tumors | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Discitis | ++ | ++ | — |

| Septic arthritis | ++ | ++ | — |

| Osteomyelitis | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Meningitis | ++ | ++ | — |

| Valid but Rare or Unusual | |||

| Rheumatoid arthritis | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Ankylosing spondylitis | ++ | ++ | — |

| Crystal arthropathies including gout | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Polymyalgia rheumatica | — | ++ | ++ |

| Longus colli tendonitis | — | ++ | — |

| Fractures | — | ++ | — |

| Miscellaneous | |||

| Torticollis | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Detectable but of Questionable Validity | |||

| Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament | — | — | ++ |

| Paget’s disease | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Spondylosis/degenerative disease | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Osteoarthritis | ++ | — | — |

| Synovial cyst | — | ++ | — |

| Neurologic | |||

| Thoracic outlet syndrome | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Spinal cord tumors | ++ | — | — |

| Nerve injuries | ++ | — | — |

| Myelopathy | — | — | ++ |

| Radiculopathy | — | — | ++ |

| Spurious or Vague | |||

| Soft-tissue injuries | — | ++ | — |

| Whiplash | — | — | ++ |

| Cervical strain | ++ | — | — |

| Psychogenic | — | — | ++ |

| Postural disorders | ++ | — | ++ |

| Fibrositis, myofascial pain | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Hyoid bone syndrome | — | ++ | — |

| Sternocleidomastoid tendonitis | ++ | — | — |

| Fibromyalgia | — | ++ | — |

These purported causes of neck pain can be grouped in 3 ways: according to clinical significance into serious or nonthreatening conditions; into common and uncommon conditions; and into valid and not valid causes.

Serious but rare conditions are the neoplasms and infections. No-one seriously doubts the legitimacy of such conditions as causes of neck pain because, by and large, they can be diagnosed by medical imaging and by biopsy, if required. However, they are rare. In population studies of patients presenting with neck pain, unsuspected tumors and infections have never been disclosed. Given the size of these studies, calculation of 95% confidence intervals reveals that serious conditions account for less than 0.4% of cases of neck pain.

Overlooked by contemporary textbooks is the importance of vascular disorders in the diagnosis of neck pain. Although headache is the most common presenting feature of internal carotid artery dissection, neck pain has been the sole presenting feature in some 6% of cases. In 17% of patients headache may occur in combination with neck pain. Neck pain has been the initial presenting feature in 50% to 90% of patients with vertebral artery dissection, but is usually also accompanied by headache, typically in the occipital region although not exclusively so. Although the typical features of dissecting aneurysms of the aorta are chest pain and cardiovascular distress, neck pain has been reported as the presenting feature in some 6% of cases. However, all of these vascular conditions are unlikely to be causes of persistent neck pain, because in due course they all develop additional clinical features, sometimes rapidly, that implicate a vascular disorder.

Less serious conditions are the inflammatory arthropathies. The validity of these conditions as a cause of neck pain is not questioned, because the condition can be detected by imaging, and these conditions are accepted, recognized causes of joint pain when they affect the joints of the appendicular skeleton. However, these conditions typically affect the neck in patients with evidence of systemic distribution of arthropathy. They are rare causes of neck pain alone.

Polymyalgia rheumatica is a valid entity, but it should not be listed as a cause of neck pain. It is a condition that may involve the neck but, by definition, it is a systemic disorder that affects other regions of the body as well. It does not present with isolated neck pain. Similar comments and deletions apply to fibromyalgia. Regardless of whether one accepts that fibromyalgia is a valid entity or not, it is, by definition, a widespread disorder, and not one that enters the differential diagnosis of neck pain as an isolated symptom.

Longus colli tendonitis is a misnomer for a condition better known as retropharyngeal tendinitis, because the condition involves more than just the tendons of the prevertebral muscles. It involves inflammation and edema of the upper portions of the longus colli (not just its tendons), from the level of C1 to C4 and even to C6. It is a rare condition, but can be diagnosed by plain radiography, and most accurately by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Fractures are an accepted cause of pain, although not all fractures are necessarily painful. As causes of neck pain, however, fractures are rare or unusual. Like tumors, unsuspected fractures proved to have zero prevalence in large population surveys, which places their prevalence at less than 0.4%. Even amongst patients presenting to emergency rooms, with suspected or possible cervical trauma, fractures are uncommon. A prevalence figure of 3.5% (± 0.5%) is representative.

Synovial cyst is a spurious cause of neck pain. There are no reports of this condition causing neck pain. When symptomatic, these cysts cause radiculopathy or radicular pain. Accordingly, they do not constitute a differential diagnosis of neck pain.

Torticollis is a clinical syndrome; it is not a specific cause of neck pain. It is characterized by fixed rotation of the head and cervical spine. The neck may or may not be painful, but the presentation does not define the cause, or even the source, of pain. In adults, known causes include basal ganglion disorders, subluxation of the lateral atlantoaxial joint, and epidural abscess. Speculative causes include subluxations of the zygapophysial joints and extrapment of their meniscoids.

Several listed conditions constitute detectable disorders but questionable sources of neck pain. Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis can be vividly shown on radiographs of affected regions of the spine, but it is often asymptomatic. When symptomatic it causes stiffness and dysphagia, rather than neck pain. Similarly, ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament can be asymptomatic. Rather than neck pain, this condition is more likely to present with myelopathy.

Paget’s disease is, as a general rule, an accepted cause of pain in the body regions affected. Technically, therefore, it is an acceptable cause of neck pain if detected in the cervical spine. However, 1 large survey found that Paget’s disease is often painless, and that patients with cervical spine involvement had no pain complaints referable to that region. This finding gives cause to doubt that Paget’s disease is ever a cause of neck pain. When diagnosed radiologically, Paget’s disease in the cervical spine may be no more than an incidental finding.

Spondylosis and osteoarthritis are perhaps the most commonly applied diagnoses in patients with neck pain with demonstrable changes on radiographs. However, neither diagnosis is valid. The radiographic features of cervical spondylosis occur with increasing frequency with increasing age in asymptomatic individuals. This finding indicates that these features are age-related changes. Most commonly they affect the C5-6 and C6-7 segments. However, these changes are weakly, if at all, associated with pain. In some studies, cervical spondylosis occurs somewhat more commonly in symptomatic individuals than in asymptomatic individuals, but the odds ratios for disc degeneration or osteoarthrosis as predictors of neck pain are only 1.1 and 0.97, respectively, for women and 1.7 and 1.8 for men. In other studies, the prevalence of disc degeneration, at individual segments of the neck, is not significantly different between symptomatic patients and asymptomatic controls. Uncovertebral osteophytes and osteoarthrosis were found to be less prevalent in symptomatic individuals. Consequently, finding spondylosis or osteoarthritis on a radiograph does not constitute making a diagnosis or finding the source of pain.

The various neurologic conditions listed in Table 2 are, by definition, not causes of neck pain. They cause symptoms, not in the neck, but in the upper limb. Furthermore, they cause loss of neurologic function rather than pain.

The remaining, listed causes of neck pain are little more than spurious labels. Yet it is these labels that are so often applied to most patients with neck pain.

Soft-tissue injury means nothing more than that something has been injured but there has not been a fracture. Whiplash describes the possible cause of the pain but not its cause or its source. Cervical strain is an ambiguous term that implies no more than that something went wrong with the neck to produce pain.

Psychogenic pain is a dated, but often abused, term. It is not admitted by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition . Unless an alternative, specific psychiatric diagnosis is proffered, psychogenic pain is a euphemism for “I don’t know what’s wrong” or for malingering.

Although sometimes invoked as a diagnosis, postural disorders may be secondary to neck pain. There is no evidence that some sort of habitual abnormal posture causes pain. Such prospective, longitudinal, long-term data as are available indicate that abnormal posture does not lead to a greater incidence of pain.

Although commonly held to be a cause of neck pain, myofascial disorders fail on several counts. The cardinal diagnostic feature for myofascial pain is the detection of a trigger point. However, there is no evidence that examiners can reliably detect trigger points in the neck, but the classic trigger points of the neck do not satisfy the prescribed criteria for a trigger point, to the extent that they are exempt from doing so. The features of cervical trigger points seem better to describe a tender, underlying zygapophysial joint, and the pain associated with those trigger points is identical in distribution to the pain that would arise from the underlying joint.

Hyoid bone syndrome is a poorly studied condition. Its features are said to be tenderness over the greater cornu of the hyoid bone. Hyoid syndrome might be included in the differential diagnosis of anterior neck pain, but it cannot be confused with posterior neck pain. The diagnostic criterion is said to be relief of pain on anesthetizing the cornu, but no studies have tested this criterion under controlled conditions.

Beyond being listed recurrently in textbooks, there is little literature on sternocleidomastoid tendonitis. The cardinal diagnostic feature seems to be tenderness over the tendons of the muscle, but this has not been distinguished from random hyperalgesia in patients with neck pain.

Implications

A sober review of the purported causes of neck pain reveals that the most readily diagnosed and serious conditions are rare, and do not account for most cases. Meanwhile, the most commonly applied diagnoses lack validity. Either they have been disproved by epidemiologic studies or they have defied testing. Other entities are descriptive terms but not proper diagnoses. For common, uncomplicated neck pain there are no data on its cause.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree