Tendon Transfers for Irreparable Rotator Cuff Tears

Peter Habermeyer

Petra Magosch

Mark Tauber

INTRODUCTION

The treatment of massive tears of the rotator cuff continues to be controversial. Despite improvements in arthroscopic repair,6,12,52,49,58 open procedures remain the treatment of choice if the size of the tear prevents direct reinsertion of the tendon and if the quality of the tendon is poor. A number of different operative techniques have been introduced to address the problem of massive tears of the rotator cuff, yet there has been no consensus.3,16,22,26,34,51,56,63,65,82,71,80

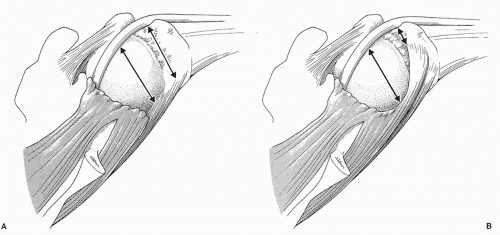

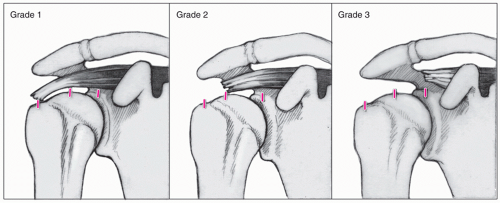

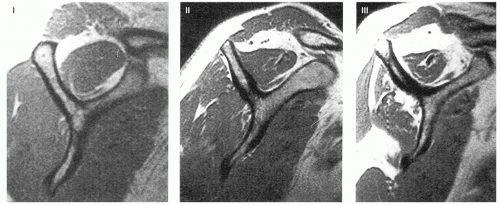

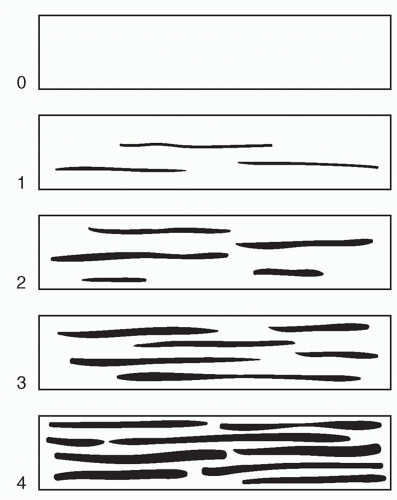

Various definitions of a massive rotator cuff tear have been proposed. Cofield defined a rotator cuff tear as a massive tear if the tear is greater than 5 cm in diameter.15 Because of variations in the sizes of patients and the techniques of measurement, Gerber et al. defined a tear as massive, if it involved the detachment of at least two complete tendons from the greater tuberosity28 (Fig. 4-1). Massive posterosuperior rotator cuff tears, involving the supra- and the infraspinatus tendon, appear more frequently than anterosuperior massive rotator cuff tears involving the subscapularis and the supraspinatus tendon. Massive rotator cuff tears occur less often as a result of an acute trauma. They usually develop on the basis of degenerative changes of the tendon and result in complete tendon tear with or without incidental trauma. The tendon tear becomes irreparable if the tendons are retracted up to or medial to the glenoid rim (grade 3 according to Patte70) (Fig. 4-2), muscle atrophy of stage 3 according to Thomazeau et al.74 (Fig. 4-3), stage 3 or 4 fatty infiltration of the muscle according to Goutallier et al.36,37 on the computed tomography (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Fig. 4-4), and a static superior migration of the humeral head with an acromiohumeral distance of 7 mm or less on an anteroposterior radiograph.28 Meyer and Gerber showed that chronic tendon tears are not only associated with tendon and muscle fiber retraction, fatty infiltration, and atrophy but also with loss of strength and contractile amplitude.61,62

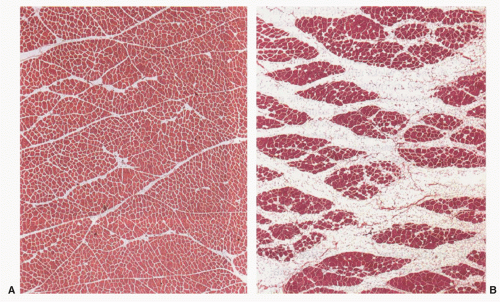

In a sheep model, fatty infiltration of the rotator cuff after an artificial chronic tear represents not a degenerative process but rather a rearrangement of the tissue after macroarchitectural changes caused by musculotendinous retraction.62 As the tendon tears and the muscle retracts, the pennation

angle of the muscle fibers increased and the mean fiber length decreased. The increase in the pennation angle leads to gap formation between the muscle fibers, which are infiltrated with fat and fibrous tissue62 (Fig. 4-5). The increase in interstitial connective tissue leads to a significantly poorer elasticity of the musculotendinous unit.33 These structural changes seem to be irreversible after standard repair, but in most cases, anatomic tendon-to-bone repair becomes impossible.33

angle of the muscle fibers increased and the mean fiber length decreased. The increase in the pennation angle leads to gap formation between the muscle fibers, which are infiltrated with fat and fibrous tissue62 (Fig. 4-5). The increase in interstitial connective tissue leads to a significantly poorer elasticity of the musculotendinous unit.33 These structural changes seem to be irreversible after standard repair, but in most cases, anatomic tendon-to-bone repair becomes impossible.33

FIGURE 4-2. Classification of tendon retraction according to Patte70: Grade 1: Proximal stump close to the bony insertion. Grade 2: Proximal stump at the level of the humeral head. Grade 3: Proximal stump at the level of the glenoid. (From Habermeyer P. Therapie der Rotatorenmanschettenruptur und der langen Bizepssehne – allgemeine Aspekte und konservative Therapie. In: Habermeyer P, Lichtenberg S, Magosch P, eds. Schulterchirurgie. Munich: Elsevier; 2010:337-350.) |

The main indications for tendon transfer for the treatment of irreparable rotator cuff tears are the loss of active elevation without superior escape of the humeral head, pseudoparalysis, and rotation in a functional demanding patient.

BIOMECHANICS/PATHOMECHANICS OF IRREPARABLE ROTATOR CUFF TEARS

The biomechanical goal of tendon transfers for the treatment of massive rotator cuff tears is to reconstruct the disturbed force couple in the transversal plane13 in case of a

massive anterosuperior, or a posterosuperior massive rotator cuff tear.

massive anterosuperior, or a posterosuperior massive rotator cuff tear.

FIGURE 4-3. Classification of supraspinatus muscle atrophy in MRI according to Thomazeau et al.74: The classification of the supraspinatus muscle atrophy is based on the occupation ratio to the supraspinatus fossa. Stage I: ratio between 1.00 and 0.6; the muscle can be considered as normal or slightly atrophied. Stage II: ratio between 0.60 and 0.40; moderate atrophy. Stage III: ratio below 0.40, serious or severe atrophy. |

FIGURE 4-4. Classification of fatty muscle degeneration in rotator cuff tears using CT-scan according to Goutallier et al.36 This classification can also be used with a T1-weighted MRI because of the high signal intensity of the fatty tissue. Stage 0: corresponds to a completely normal muscle, without any fatty streak; Stage 1: the muscle contains some fatty streaks; Stage 2: important fatty infiltration, but there is still more muscle than fat; Stage 3: there is much fat as muscle; Stage 4: more fat than muscle is present. |

The subscapularis, infraspinatus, and teres minor muscles are primary depressors of the humeral head during shoulder motion. If this force couple between the anterior and the posterior part of the rotator cuff is unbalanced due to either a massive anterosuperior or posterosuperior rotator cuff tear, the humeral head cannot be centered into the glenohumeral joint during shoulder movement resulting in the loss of shoulder function.

PECTORALIS MAJOR TENDON TRANSFER FOR IRREPARABLE ANTEROSUPERIOR ROTATOR CUFF TEARS

Insufficiency of the subscapularis tendon results in severe disability of the shoulder creating pain and loss of internal rotation and anterior elevation. Tears involving the subscapularis tendon are less frequent than tears of the supraspinatus and are often underdiagnosed68 with a reported prevalence of up to 8%24 (25 of 301 full-thickness rotator cuff tears). They are either isolated,21,31 part of a massive rotator cuff tear,28,68,78 or associated with recurrent anterior dislocation of the shoulder.66,67,75 Further, subscapularis tendon insufficiency can result from tenotomy after anterior shoulder arthrotomy via an anterior deltoideopectoral approach.

From a biomechanical view, subscapularis deficiency creates anteroposterior muscle imbalance of the glenohumeral joint resulting in anterior subluxation of the humeral head.

Clinically, increased passive or active external rotation or a decreased active internal rotation and weakness of anterior elevation indicate a progressed tendon lesion. Usually, an accurate clinical examination using specific clinical tests allows for adequate clinical diagnosis and quantification of subscapularis tendon tears. The current evaluated clinical tests to detect subscapularis deficiency are the lift-off test,31 the internal rotation lag sign according to Hertel,42 the belly-press test,29 the Napoleon test,11 the belly-off-sign,72 and the bear-hug test.5

Imaging diagnosis is performed by ultrasound or MRI, where muscle belly atrophy and grade of fatty degeneration can

be evaluated, as well. In cases of chronic tears with an irreparable subscapularis tendon tear, the indication for muscle transfer is given. An irreparable tear is defined by either advanced and irreversible muscle retraction or progressed muscle atrophy grade 3 according to the classification of Thomazeau et al.74 and progressed fatty degeneration grade 3 or 4 according to the classification system of Goutallier.36

be evaluated, as well. In cases of chronic tears with an irreparable subscapularis tendon tear, the indication for muscle transfer is given. An irreparable tear is defined by either advanced and irreversible muscle retraction or progressed muscle atrophy grade 3 according to the classification of Thomazeau et al.74 and progressed fatty degeneration grade 3 or 4 according to the classification system of Goutallier.36

FIGURE 4-5. (A) HE-stained crosssection of normal muscular tissue. (B) HE-stained cross-section of a fatty infiltrated muscle: gaps between the muscle fibers are infiltrated with fat and fibrous tissue.62 |

Reconstructive options include transfer of the trapezius, pectoralis minor, or pectoralis major muscles,30,64,71,80,82,83 with the best results reported for the pectoralis major transfer. Various technical modifications have been described including transfer of the pectoralis major in a supracoracoid fashion to the greater tuberosity anterior to the conjoined tendon,51,82,83 whereas Resch et al.71 imitated a more anatomic, subscapularis-like vector in reconstruction by transferring the pectoralis major posterior to the conjoined tendon to the lesser tuberosity. Both authors used the proximal half of the tendon’s insertion for subscapularis reconstruction, whereas Galatz et al.25 transferred the entire pectoralis major tendon in a subcoracoid fashion with attachment to the greater tuberosity. Some surgeons advocate use of the sternocostal portion of the pectoralis major muscle.48 However, with the latter technique postoperative cases of musculocutaneous neurapraxia were encountered as a result of the bulky tendon, and hence, a split tendon transfer remains the preferred option.

BIOMECHANICS OF PECTORALIS MAJOR TRANSFER

The main biomechanical principle of the pectoralis major muscle transfer in chronic irreparable subscapularis tendon tears is the restoration of the horizontal muscular force couple to balance posteroanterior humeral head translation and to prevent a coracohumeral impingement. The various technical modifications of pectoralis major muscle transfer show different biomechanical principles. Initially, a debate was active if the course of the transfer should be superficial or underneath the conjoined tendon. Konrad et al.54 could show in a biomechanical study that transferring the superior half of the pectoralis major muscle underneath the conjoined tendon restored glenohumeral kinematics that were closer to those in the intact shoulder than were those of the transfer of the muscle above the conjoined tendon.

Another aspect represents the part of tendon’s insertion used for transfer. Usually, the proximal half71,82 is used for transfer of the pectoralis major muscle including consecutively parts of both laminae, the anterior one representing the clavicular portion and the posterior one representing the sternal portion. Galatz et al.25 detached the entire pectoralis major tendon insertion, whereas Jennings et al.48 proposed a technique after performing a cadaver study using a segmentally split pectoralis transfer of the sternalcostal portion alone, which may provide a transfer with a vector more closely matching that of the functioning subscapularis muscle.

Regardless of the portion pectoralis major used, care has to be taken in relation to the musculocutaneous nerve, which has to be visualized and left underneath the transferred muscle.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE OF PECTORALIS MAJOR TRANSFER

Out of the biomechanical rationales, we prefer the technique described by Resch et al.71 for conducting muscle transfer underneath the conjoined tendon to the lesser tuberosity.

The procedure is performed in the beach-chair position under general endotracheal anesthesia combined with an interscalene cervical plexus block. A deltopectoral approach provides identification of the conjoined tendon, the insertional area of the pectoralis major at the crest of the greater tuberosity and the lesser tuberosity with the subscapularis tendon avulsion. Subscapularis reconstruction should be performed to restore at least the muscular portion together

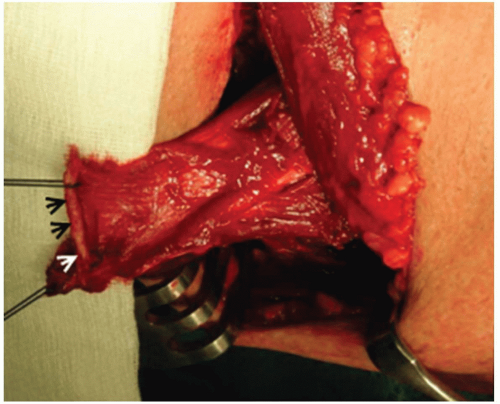

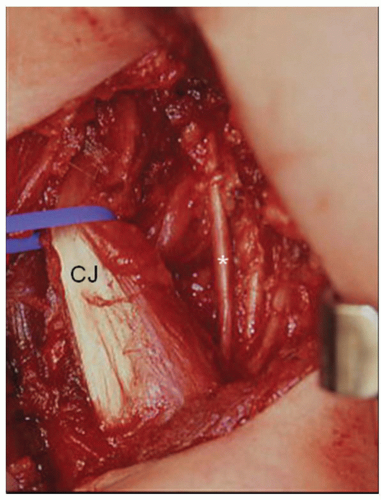

with the inferior capsule. In case of subluxation or dislocation of the long head of the biceps tendon out of the bicipital groove, a tenodesis should be performed. Isolation and preparation of the pectoralis major muscle is carried out by identifying the clavicular and sternal portions. The tendon is released from the humerus and mobilized medially. Care has to be taken not to mobilize more than 8 cm from the lateral border of the muscle in order to protect the lateral pectoral nerve.53 The amount of tendon release from the humeral insertion depends on the rotator cuff tear size. For isolated subscapularis tendon tears the proximal one half of the tendon is released, whereas for combined anterosuperior rotator cuff tears involving the subscapularis and supraspinatus tendons the proximal two thirds are harvested. To improve primary fixation strength and tendon ingrowth, we recommend tendon harvesting with a thin wafer of bone from the humeral insertion (Fig. 4-6) in order to gain bone-to-bone fixation at the lesser tuberosity. This is performed with an osteotome. This slight technical modification showed superior clinical results due to a reduced rate of re-rupture.56 Two to three number 2 non-absorbable stay sutures are placed behind the bone chip in the tendon. The clavicular and sternal portions are split from lateral to medial over a distance of 8 cm protecting the lateral pectoral nerve. The fascia between the conjoined tendon and the pectoralis minor has to be split for 5 to 6 cm directly at the medial border of the conjoined tendon. Beneath the fascia the perineural fat pad protects the brachial plexus. We strongly recommend dissecting the musculocutaneous nerve and identifying its entrance into the coracobrachial and biceps muscles (Fig. 4-7), which on average is about 5 cm (range, 2 to 11 cm) inferior to the tip of the coracoid process.53,71 Using stay sutures, the mobilized pectoralis muscle flap is routed underneath the conjoined tendon to the humeral head. If the transfer is felt to place the musculocutaneous nerve under tension, the small proximal branch entering the muscle of the coracobrachialis superior to the main body of the nerve should be released. Thus, the main innervation to the biceps should be unaffected.

with the inferior capsule. In case of subluxation or dislocation of the long head of the biceps tendon out of the bicipital groove, a tenodesis should be performed. Isolation and preparation of the pectoralis major muscle is carried out by identifying the clavicular and sternal portions. The tendon is released from the humerus and mobilized medially. Care has to be taken not to mobilize more than 8 cm from the lateral border of the muscle in order to protect the lateral pectoral nerve.53 The amount of tendon release from the humeral insertion depends on the rotator cuff tear size. For isolated subscapularis tendon tears the proximal one half of the tendon is released, whereas for combined anterosuperior rotator cuff tears involving the subscapularis and supraspinatus tendons the proximal two thirds are harvested. To improve primary fixation strength and tendon ingrowth, we recommend tendon harvesting with a thin wafer of bone from the humeral insertion (Fig. 4-6) in order to gain bone-to-bone fixation at the lesser tuberosity. This is performed with an osteotome. This slight technical modification showed superior clinical results due to a reduced rate of re-rupture.56 Two to three number 2 non-absorbable stay sutures are placed behind the bone chip in the tendon. The clavicular and sternal portions are split from lateral to medial over a distance of 8 cm protecting the lateral pectoral nerve. The fascia between the conjoined tendon and the pectoralis minor has to be split for 5 to 6 cm directly at the medial border of the conjoined tendon. Beneath the fascia the perineural fat pad protects the brachial plexus. We strongly recommend dissecting the musculocutaneous nerve and identifying its entrance into the coracobrachial and biceps muscles (Fig. 4-7), which on average is about 5 cm (range, 2 to 11 cm) inferior to the tip of the coracoid process.53,71 Using stay sutures, the mobilized pectoralis muscle flap is routed underneath the conjoined tendon to the humeral head. If the transfer is felt to place the musculocutaneous nerve under tension, the small proximal branch entering the muscle of the coracobrachialis superior to the main body of the nerve should be released. Thus, the main innervation to the biceps should be unaffected.

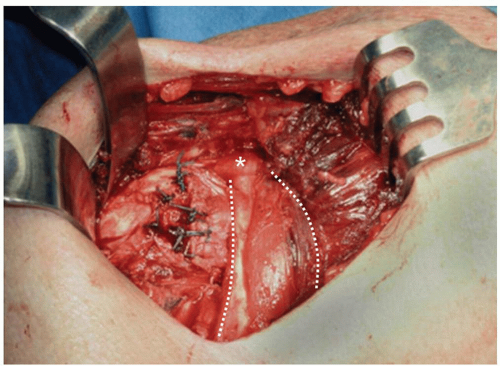

Fixation of the tendon should be to the anatomical reinsertion at the lesser tuberosity in order to maintain the force vector of the muscle.69 The original subscapularis tendon footprint is decorticated and bone-to-bone fixation is performed using four to five transosseous sutures with the arm in neutral rotation (Fig. 4-8). Alternatively, anchor fixation using two to three screw anchors can be carried out. A double-row fixation is recommended. In some cases, the tendon transfer is too long showing insufficient pretension when being attached to the lesser tuberosity. In these rare cases, advanced fixation of the tendon should be performed lateral to the bicipital groove at the greater tuberosity. In patients with combined irreparable anterosuperior rotator cuff tears involving the subscapularis and supraspinatus tendons, the bone chip should be fixed as high as possible in order to gain humeral head depression forces.

Rotational control should check subcoracoid entrapment. Finally, the wound is closed in layers over suction drainage.

GERBER’S TECHNIQUE OF PECTORALIS MAJOR TRANSFER50

An extended deltopectoral approach is performed with the patient in the beach-chair position. The entire humeral insertion of the pectoralis major muscle is exposed from superior to inferior. After accurate evaluation of the rotator cuff defect and attempt of rotator cuff repair, at least partial reconstruction of the subscapularis tendon should be performed. In most cases, the inferior portion of the subscapularis tendon can be reinserted anatomically and should be repaired in addition to the pectoralis major transfer. The entire tendinous insertion of the pectoralis major is sharply released from the humerus in order to gain maximum length and mobilized medially to the muscle belly. For tendon passage the tendon is tagged with three number 3 braided sutures in a modified Mason-Allen configuration. The pectoralis tendon is transferred to the medial aspect of the greater tuberosity lateral from the bicipital groove coursing superficially to the conjoined tendon. Anatomical reinsertion at the lesser tuberosity is not performed for two reasons: (1) to provide a certain amount of pretension to the transferred muscle in order to evolve sufficient internal rotation contraction forces and (2) to not disrupt a prior repair of native subscapularis tendon. The tendon is fixed transosseously into a bony trough created using a high-speed burr. In order to prevent cutting through of the transosseous sutures, a cortical augmentation device is used.

WARNER’S TECHNIQUE OF PECTORALIS MAJOR TRANSFER27

The procedure is performed with the patient in the beachchair position. An extended deltopectoral approach allows for a sufficient exposure of the humeral insertion of the pectoralis major muscle. The interval between the deltoid and the pectoralis major is dissected with release of subdeltoid adhesions. Any bursal and scar tissue at the lesser tuberosity is resected, which may be mistaken for native subscapularis tendon tissue, which has been retracted medially beneath the conjoined tendon. Partial reconstruction of the subscapularis tendon, in most cases the inferior third, is recommended whenever possible, in order to improve anterior stability of the humeral head. For pectoralis major transfer, only the sternalcostal part is used. Thus, the clavicular and sternalcostal portions are divided at the humeral insertion. The tendon of the sternalcostal portion is invariably inferior and underneath to the clavicular portion and the interval between these two tendons can be easily developed at the humeral insertion. Only the sternalcostal part is sharply released from the humerus and armed with braided tagging sutures in a modified Mason-Allen configuration. Mobilizing the muscle belly medially, attention has to be kept not to damage the lateral pectoral nerve at a distance of 10 cm. The sternalcostal head is passed beneath the clavicular head and superficially to the conjoined tendon to the lesser tuberosity. Tendon fixation is performed either transosseously or using bone anchors in such a way that approximately 30 degrees of external rotation is possible.

In combined chronic irreparable anterosuperior rotator cuff tears involving the subscapularis and supraspinatus tendons, a transfer of the teres major muscle is performed in addition to the pectoralis major. In order to expose the humeral insertion of the teres major, the latissimus dorsi is detached from the humerus with the arm in maximal external rotation. Detachment should be performed leaving a short stump at the humeral insertion in order to enable later tendon reattachment. The teres major muscle is dissected medially avoiding damage of its neurovascular pedicle which enters at a distance of 7 cm medially from the humeral insertion. Non-absorbable braided number 2 sutures are used as tagging sutures for the tendon. Mobilizing the teres major muscle, care has to be taken for the axillary nerve which runs along the superior border of the muscle. The sternalcostal head of the pectoralis major tendon and the teres major are then passed underneath the clavicular head of the pectoralis major and reattached to the lesser tuberosity. The teres major is used to restore the subscapularis tendon and the sternalcostal head of the pectoralis major is passed lateral to the bicipital groove in order to restore, at least partially, the supraspinatus tendon. Finally, the latissimus dorsi tendon is reattached to its humeral insertion.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree