Tendinitis/Bursitis/Subacromial Impingement

Joseph A. Abboud

William J. Warrender

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

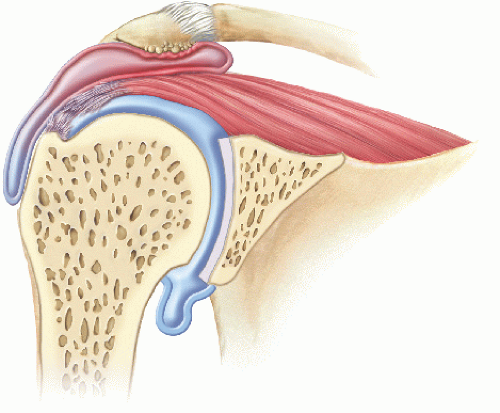

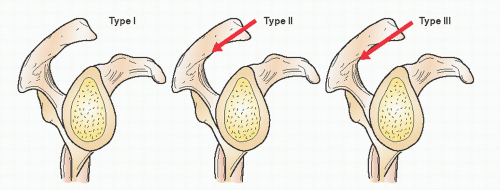

Subacromial impingement, also known as rotator cuff tendinitis or bursitis, occurs when the rotator cuff becomes irritated underneath the acromion. The reason why this happens is unclear. Some people are thought to be born with a “hooked” acromion that will predispose them to impingement. Other patients develop impingement due to intrinsic rotator cuff weakness. Because the rotator cuff is a humeral head centralizer, weakness of the cuff will allow it to ride up and impinge on the acromion. The result is inflammation of the bursa between the rotator cuff and the acromion.

The typical patient presents with a recent history of overactivity and onset of moderate to occasionally severe pain with active range of motion of the shoulder.1 A complete history of the patient is critical in the diagnosis of subacromial impingement syndrome, and it is important to identify predisposing factors, such as participation in sports- or work-related activities, that involve overhead motion. Patients often complain of pain on the top and front of the shoulder. Either way, pain is the most common symptom. Symptoms also include localized tenderness, inflammation, edema, and loss of function. Weakness and stiffness of the shoulder also may occur, but this is usually secondary to pain and not muscle weakness. When the pain is eliminated, the weakness and stiffness generally resolve. If the weakness persists, the patient should be evaluated for a tear of the rotator cuff or a neurologic etiology (i.e., cervical radiculopathy or suprascapular nerve entrapment). If the stiffness persists, the patient may have a frozen shoulder, inflammatory arthritis, or calcific tendinitis.

It is important to establish the position of maximum pain, quality of the pain (dull or severe), timing of the pain (during the day or at night), and association between pain and activity (i.e., the presence or absence of pain during sleep and during movement). Most symptoms of impingement begin gradually and have a chronic component that progresses over several months.2 Sometimes, the bursitis that occurs with rotator cuff tendinitis can cause a mild popping or cracking sensation in the shoulder that can be annoying to the patient. Finally, it is important to document all treatment modalities attempted, including changes in lifestyle, physical therapy regimens, use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), subacromial injections, and operative procedures on the shoulder.

Impingement syndrome is more common in patients who are >40 years of age. However, in patients who are <40 years, the diagnosis of impingement syndrome must be approached cautiously, as these patients may have subtle glenohumeral instability as the underlying problem.3 Unfortunately, these two processes cannot be differentiated on the basis of an accurate history alone. However, it is rare that someone <40 years presents with isolated impingement syndrome.

CLINICAL POINTS

Pathology involves inflammation of the bursa between the rotator cuff and the acromion.

The most common symptom is pain.

The condition is more common in adults who are >40 years of age.

EXAMINATION

The physical examination should help in confirming or refuting the initial diagnosis that is made on the basis of the history.

A careful examination of the cervical spine should be performed to rule out any abnormalities, including radiculopathy and degenerative joint disease that may cause referred pain in the shoulder. It is important to remember that patients can have problems with their neck and shoulder, and this needs to be further substantiated or refuted on exam.

Next, the shoulder is inspected and palpated, and the muscle strength as well as the range of motion is assessed.

Range of motion of the shoulder is performed actively and passively and compared with that of the asymptomatic side.4

Several tests are helpful in diagnosing impingement syndrome:

The impingement sign, as described by Neer (see Fig 35-10), is elicited by standing behind the patient and passively elevating the arm in the scapular plane while stabilizing the scapula.5 Pain usually is elicited in the arc between 50 and 130 degrees of forward elevation. The acromiohumeral distance is decreased substantially in this range of motion as the greater tuberosity passes under the acromion. This distance is decreased further by internally rotating the humerus or the presence of an acromial spur (Fig. 36-1).

Hawkins sign, a modification of the above maneuver, is elicited by passively internally rotating the arm after passively elevating the arm to 90 degrees2 (see Fig 35-11). Remember, it may be difficult to elicit the impingement or Hawkins sign in a patient who has a stiff shoulder that is unable to pass through this range of motion.

The impingement test can be a useful adjunct in diagnosing impingement. After sterile injection of 10 mL of lidocaine (Xylocaine) into the subacromial space, the test for the impingement sign is repeated. When the abnormality is confined to the subacromial space, the injection eliminates the pain in most patients.4

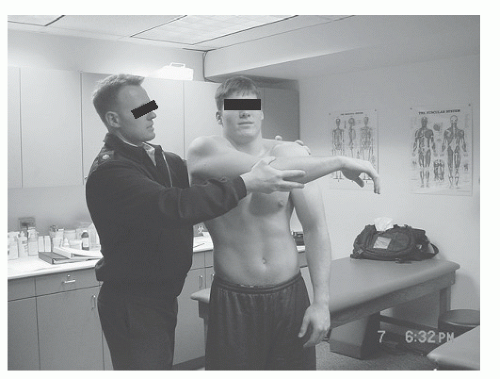

FIGURE 36-2. This is a cross body adduction maneuver that compresses the AC joint. A positive test produces pain on top of the shoulder. (From Tokish JM. Clinical examination of the overhead athlete: the differential directed approach. In: Krishnan SG, Hawkins RJ, Warren RF, eds. The Shoulder and the Overhead Athlete. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004:33.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|