Synovectomy of the Elbow

Michael J. O’Brien

J. Ollie Edmunds Jr.

Felix H. Savoie III

DEFINITION

Elbow synovectomy surgically removes the thickened, inflamed, and painful synovium of the elbow joint.

Synovectomy is commonly performed for rheumatoid arthritis, hemophiliac synovitis, synovial chondromatosis, and inflammatory arthropathies.

In the past, synovectomy has been performed through an open arthrotomy, but currently, arthroscopic synovectomy is the treatment of choice.

Compared with open synovectomy, arthroscopic synovectomy can be performed as an outpatient procedure, allows more rapid recovery, and offers visualization of the entire elbow joint and recognition of concomitant pathology.

ANATOMY

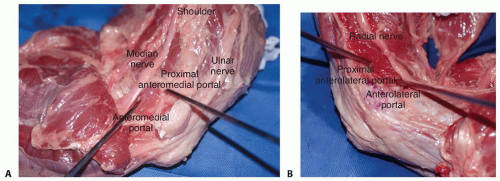

On the medial side of the elbow, knowledge of the location of the median and ulnar nerves is essential for the safe establishment of medial portals (FIG 1A).

On the lateral side, knowledge of the location of the radial nerve and posterior interosseous nerve (PIN) is essential for the safe establishment of lateral portals (FIG 1B).

Proximal portals are safer than distal portals, as they are further away from the neurovascular structures.

Posterior portals should never stray medial to midline to avoid iatrogenic damage to the ulnar nerve.

Proliferation of the synovium and distension of the joint capsule may result in compression neuropathies of the radial or ulnar nerves.

PATHOGENESIS

Rheumatoid disease is a chronic, systemic autoimmune condition that causes a microvascular disease of the synovium and synovial cell proliferation with perivascular lymphocytosis.13

Synovial tissue hypertrophy is the hallmark of the disease.

Inflammation of the synovium causes a joint effusion, leading to pain, swelling, and limited range of motion.

Continued inflammation results in the formation of an erosive, hyperplastic synovium known as a pannus. The release of inflammatory cytokines results in continued cartilage damage, periarticular bone erosions, and soft tissue degradation.14

Capsular distension and synovial hypertrophy can lead to gradual ligamentous, cartilaginous, and bony destruction resulting in progressive instability and deformity.

Recurrent hemarthroses in factor 8 or 9 deficient hemophiliac patients often leads to hemophiliac arthropathy. Hemarthroses lead to blood absorption by the synovium with reactive synovitis which causes the synovium to produce proteolytic enzymes to destroy the blood, articular cartilage, and adjacent bone.

NATURAL HISTORY

The patient with elbow synovitis will initially present with an elbow effusion, with pain, and restriction of motion. In early stages of inflammatory arthritis, deformity of cartilage and bone are not present. In the case of hemophiliac synovitis, the swollen hypervascular synovium is friable and recurrently bleeds into the elbow joint.

In 10% of rheumatoid patients, synovitis will spontaneously resolve.7

In the rheumatoid patient, early medical management may slow natural disease progression.2 This should be attempted prior to surgical intervention.

If synovitis persists, secondary changes may occur.

A fixed flexion contracture may result from the patient holding the elbow in a flexed position to minimize pain caused by joint motion and capsular distension.

The disease may result in atrophy of the brachialis muscle, bringing the median nerve and brachial artery much closer to the synovial lining.

Destruction of the annular ligament may cause radial head instability with anterior displacement resulting from the pull of the biceps brachii muscle.

Damage to either or both of the medial collateral ligament and lateral collateral ligament (LCL) complexes may result in gross mediolateral elbow instability.

Proliferation of the synovium or distension of the joint capsule into the forearm may result in vascular, neural, or muscular dysfunction, particularly compression neuropathies of the ulnar or radial nerves.

Prolonged synovitis ultimately results in erosion of the articular hyaline cartilage.

Progressive cartilage degeneration and advancing arthritis is associated with subchondral cyst and marginal osteophyte formation, further weakening the joint capsule and ligamentous supports. Hemophiliac arthropathy of the elbow may create pseudocysts in the adjacent bone.

The end stage of disease in the elbow is marked by severe loss of joint space, damage to subchondral bone and collapse, and progressive elbow instability. This results in a joint that is painful, weak, and unstable.7

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Patients will present with a chief complaint of pain and stiffness in the elbow, especially in early stages of synovitis. Stiffness is typically the biggest problem, with loss of terminal flexion and extension. Pain may be present at rest and exacerbated by activities.

Patients may report swelling and fullness in the elbow with impingement-type symptoms.

Hemophiliac patients often report recurrent painful bleeding into the joint.

Physical examination often reveals a boggy swelling posterolaterally, indicative of synovitis or effusion. Effusion and synovial hypertrophy can be palpated in the anconeus triangle and posterolateral gutter.

Elbow range of motion in flexion, extension, and forearm rotation should be measured with a goniometer. If there is loss of motion, a soft end point suggests a soft tissue cause, such as tense effusion with synovitis or capsular contracture, whereas a firm end point suggests osseous deformity. Limited rotation may be caused by radial head deformity or instability.

In rheumatoid patients with loss of rotation, examination and imaging of the wrist is important to evaluate for pathology of the distal radioulnar joint, which is commonly involved in these patients.

Hemophiliac patients most often have an elbow flexion contracture, even if it is painless.

Ligamentous examination includes varus and valgus stress testing to evaluate the collateral ligaments. The supine lateral pivot shift test and push-off test evaluate for posterolateral rotatory instability (PLRI). The radial head should be palpated during forearm rotation to evaluate for deformity or instability.

Elbow instability is usually associated with more advanced disease, when joint effusion and synovial hypertrophy have caused ligamentous incompetence. Crepitus may present as degeneration of articular cartilage develops.

A routine neurovascular examination is essential. The PIN and ulnar nerve may be compressed by synovitis.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Plain radiographs include anteroposterior (AP), lateral, and oblique views to evaluate the degree of joint destruction. This aids in predicting the efficacy of synovectomy for pain relief.

The Mayo classification of rheumatoid elbows12 grades the severity of disease based on radiographic appearance (FIG 2A-E).

Grade I is primarily synovitis with no radiographic changes other than periarticular osteopenia or soft tissue swelling (FIG 2A,B).

Grade II shows narrowing of the joint, but the architecture of the joint is intact (FIG 2C).

Grade III demonstrates alteration of the subchondral architecture of the joint, such as thinning of the olecranon or resorption of the trochlea or capitellum (FIG 2D-E).

Grade IV shows gross destruction of the joint.

Grade V is ankylosis.

The Arnold and Hilgartner classification of hemophiliac arthropathy is divided into five stages from mild to severe.1

Computed tomography (CT) is helpful to better define osseous anatomy, such as osteophyte formation, radial head deformity, or loose bodies.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can determine the extent of synovitis, intra-articular nonossified loose bodies, and the integrity of the collateral ligament complexes.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Rheumatoid arthritis

Inflammatory arthropathies (Lupus, psoriatic arthritis)

Hemophilic arthropathy

Pigmented villonodular synovitis (PVNS)

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Systemic antirheumatoid agents may help control inflammation in rheumatoid patients.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS)

Infusion of specific clotting factors for factor-deficient hemophilia patients, according to their specific deficiency

Judicious use of intra-articular corticosteroid injections

Physical therapy to control swelling and regain range of motion

Dynamic bracing to improve terminal flexion/extension

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Indications for surgery are persistent, painful synovitis with functional impairment despite a trial of appropriate nonoperative management.

Indicated for rheumatoid arthritis (most common), inflammatory arthropathies, hemophilia with recurrent painful elbow hemarthroses, psoriatic arthritis, and acute septic arthritis.

Contraindications: inadequate medical management for at least 6 months and gross instability of the elbow joint with bony destruction and ligamentous incompetence, as synovectomy alone will not adequately address all of the pathology. Radial head resection is contraindicated in elbows with preexisting instability.

Contraindications to arthroscopic synovectomy: inadequate expertise of the surgeon, as distorted anatomy with a thin capsule with close proximity of neurovascular structures make iatrogenic injury a concern

Preoperative Planning

Patients with rheumatoid disease often have multiple joints affected. Typically, the most symptomatic joint will be operated on first. If the elbow and shoulder are equally

symptomatic, most surgeons will advocate operating on the elbow first.

Every patient with rheumatoid disease must receive a thorough evaluation of the cervical spine for instability prior to any purposed surgery.

Surgery on hemophilia patients must be carefully coordinated with the hematology team to ensure the appropriate delivery of clotting factors in the immediate pre-, intra-, and postoperative periods.

Patient positioning must be considered if concomitant procedures are to be performed on the elbow, wrist, and shoulder.

Examination under anesthesia should be performed at the beginning of every case to determine preoperative range of motion, the presence of soft or firm end points to motion, ligamentous stability, and the presence of ulnar nerve subluxation. A subluxating ulnar nerve may necessitate a small incision to identify and protect the ulnar nerve.

Positioning

For arthroscopic synovectomy, three patient positions are acceptable. Use of a pneumatic tourniquet is standard.

Prone: The upper arm is supported by a bolster or arm holder. This stabilizes the arm and provides excellent access to the posterior compartment. The arm can be externally rotated through the shoulder if a lateral approach is necessary. With this position, airway management is more difficult for the anesthesia team.

Lateral decubitus: The patient is placed on a beanbag and the arm is supported by an arm holder. This also stabilizes the arm and provides excellent access to the posterior compartment, and airway management is more accessible for the anesthesia team.

Supine: The arm is suspended with an arm suspensory device. The arm is not stabilized as well as when using the arm holder. Airway management is not an issue.

FIG 3 • The prone position for elbow arthroscopy, with the arm supported by a bolster, provides excellent access to the posterior compartment.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access