The role of surgery in the management of dysphagia is clear in some areas and controversial in others. Evaluation for the causes of dysphagia can elucidate conditions in which surgery can improve safety, quality of life, or both. Surgical therapy, when indicated, is safe and effective for many causes of dysphagia. This article includes a general overview of the causes of dysphagia that can be addressed successfully with surgery as well as a discussion of why surgery may be less appropriate for other conditions associated with dysphagia.

Dysphagia encompasses a wide range of etiologies. Its proper evaluation and treatment uses tools and expertise from a variety of specialties working toward the common goals of safety and satisfactory quality of life. Most causes of dysphagia do not require surgical intervention to accomplish these goals; however, several entities warrant surgery to treat a specific problem or to augment medical/therapeutic management. As medicine has made amazing technological and pharmacologic advances, it also has sought a more holistic approach to patients, including quality of life as an integral part of care. Certain surgical therapies for dysphagia address this perspective.

The head and neck surgeon can be an important member of the dysphagia rehabilitation team. This role maybe underemphasized in the current era of percutaneous gastrostomy tubes and accelerated medical care. The role of surgery is well defined for some causes of dysphagia and is less well defined for others. For example, the management of glottic insufficiency, Zenker’s diverticulum, cricopharyngeal dysfunction, pharyngoesophageal stricture, and sialorrhea, as related to dysphagia, routinely includes surgery ( Table 1 ). In contrast, the role of surgery for dysphagia in patients who have progressive neuromuscular disease, stroke, or polyneuropathy is less well defined and controversial. This article includes a general overview of the causes of dysphagia that can be addressed successfully with surgery as well as a discussion of why surgery may be less appropriate for other conditions associated with dysphagia.

| Indication | Intervention |

|---|---|

| Cricopharyngeal dysfunction | Botox injection |

| Cricopharyngeal myotomy | |

| Zenker’s diverticulum | Cricopharyngeal myotomy with diverticulum resection, endoscopic or external approach |

| Glottic insufficiency | Temporary: injection laryngoplasty |

| Permanent: repeated injection laryngoplasty, medialization thyroplasty with or without arytenoid adduction | |

| Intractable aspiration | Laryngotracheal separation |

| Total laryngectomy | |

| Sialorrhea | Relocation of salivary ducts |

| Excision of submandibular salivary glands |

Cricopharyngeal dysfunction

The cricopharyngeus muscle is situated at the junction of the hypopharynx and the esophagus and is integral to the complex swallowing action. This muscle maintains a static contraction with momentary relaxation during the pharyngeal swallow to allow passage of the bolus into the esophagus. The cricopharyngeus muscle then contracts actively, initiating the primary peristaltic wave of the esophagus . Accordingly, temporal parameters of muscle relaxation and contraction are critical to the initiation of the esophageal phase of the swallow.

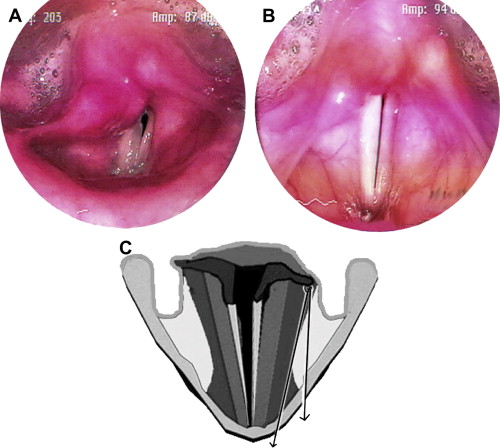

Nearly all cases of cricopharyngeal dysfunction produce signs and symptoms of dysphagia, including reported choking or difficulty swallowing, multiple attempts at swallowing a bolus, nasopharyngeal reflux, globus, aspiration, and regurgitation. Cricopharyngeal dysfunction generally manifests as a cricopharyngeal bar ( Fig. 1 A , B), cricopharyngeal spasm, or a sluggish, incoordinated cricopharyngeus muscle visualized on lateral-view barium-contrast video swallow studies . The mechanisms of dysfunction include isolated or esophageal reflux-induced spasm and hypertonicity; neuropathy with poor coordination, muscular contractions, and incomplete cricopharyngeus muscle relaxation; muscular stiffening secondary to inflammation from internal (myositis) and external (radiation) sources; and combined causes as seen with aging . Disorders such as myasthenia gravis, muscular dystrophy, and stroke may be associated with incoordination of the pharyngeal constrictors and the cricopharyngeal muscle, which may lead to dysphagia . Other conditions that may cause cricopharyngeal dysfunction resulting in dysphagia include amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, multiple sclerosis, and injuries to the vagus nerve, pharyngeal nerve plexus, and recurrent laryngeal or superior laryngeal nerves . Additionally, cricopharyngeal opening is related to hyolaryngeal elevation and forward traction as well to pharyngeal bolus-propulsive forces; therefore any weakness of the lingual or pharyngeal muscle can decrease cricopharyngeal opening, resulting in abnormally high hypopharyngeal pressures during swallowing.

Cricopharyngeal dysfunction should be considered in any patient who presents with dysphagia . Factors indicating potential cricopharyngeal dysfunction include diet modification, weight loss, globus sensation, aspiration, cough, and regurgitation . Patients who have symptomatic cricopharyngeal dysfunction should be referred to the dysphagia team for assessment and management to prevent malnutrition, dehydration, and aspiration pneumonia . Therapeutic modalities for cricopharyngeal dysfunction include mechanical dilatation and chemical denervation with botulinum toxin injections as well as surgical weakening with cricopharyngeal myotomy.

Management of cricopharyngeal dysfunction: botulinum toxin injection

Botulinum toxin injection of the cricopharyngeus muscle leads to relaxation of the upper esophageal sphincter. It is useful for cricopharyngeal achalasia and spasm. It often is done under general anesthesia for direct visualization of the cricopharyngeus muscle to ensure accurate drug placement, but it can be done in an awake patient in the office aided by electromyography . The effect of botulinum toxin is temporary, and repeat injections may be required. Because botulinum toxin may spread to adjacent tissues, the accuracy of the injection and the use of the lowest effective dose are essential for success. Inadvertent diffusion to the adjacent muscles of the larynx can lead to voice and airway problems.

Botulinum toxin injection for cricopharyngeal muscle dysfunction has been shown to improve swallowing ability in approximately 75% of patients . Improvement was assessed via patient report and by objective measures of esophageal manometry, videofluoroscopy, and laryngeal electromyography. In patients who did not have a positive response to botulinum toxin injection, cricopharyngeal myotomy was shown to improve dysphagia 70% of the time .

Management of cricopharyngeal dysfunction: cricopharyngeal myotomy

Cricopharyngeal myotomy is a surgical procedure that involves cutting the cricopharyngeus muscle, using either an external or an endoscopic approach. The endoscopic approach may be performed with the use of a laser such as a carbon dioxide or neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet laser. The former is favored because it has less collateral thermal tissue interaction ( Fig. 1 C) . Myotomy has the advantage of affecting both the muscular and connective tissue components of the cricopharyngeus. It can be effective in the treatment of inflammatory and fibrotic disorders where botulinum toxin may fail. It is the recommended surgical treatment for hypertonicity of the cricopharyngeus muscle as determined by esophageal manometry and is part of the surgical therapy for Zenker’s diverticula . Cricopharyngeal myotomy generally is indicated if patients have moderate to severe dysphagia and sequelae such as weight loss and pneumonia, if there are obvious physical findings on radiographic studies, and if the patient can tolerate surgery . Cricopharyngeal myotomy has been shown to normalize the upper esophageal sphincter relaxation pattern, allowing a more normal swallow and thereby decreasing dysphagia . Generally, the endoscopic approach is preferred because it is shorter in duration and is less invasive than the external approach. The endoscopic approach has fewer associated risks but may have a slightly higher a risk of mediastinitis and is not possible in all patients because of the limitations of rigid endoscopy . Possible complications of the external approach include hemorrhage, hematoma, damage to the recurrent laryngeal nerve, wound infection, and pharyngocutaneous fistula.

The role and timing of surgery for patients who have mild or intermittent symptoms and less obvious cricopharyngeal pathology on swallowing studies is controversial. These patients maybe taught swallowing strategies such as the Mendelsohn maneuver (ie, lifting or elevating the larynx with the muscles of the neck for a few seconds during the swallow to encourage the upper esophageal sphincter to open) or effortful swallowing (ie, bearing down or “squeezing” the neck muscles during the swallow) with the goal of compensating for the poor cricopharyngeus function. The addition of simple procedures such as transoral myotomy, cricopharyngeal dilatation, and/or botulinum toxin injections could augment the swallowing therapy and, in many cases, could guarantee its success.

Zenker’s diverticulum

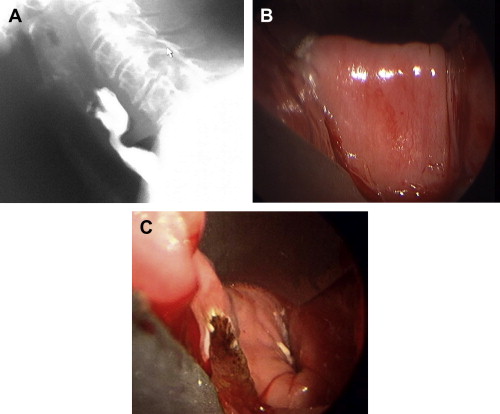

Zenker’s diverticulum ( Fig. 2 ) is within the spectrum of cricopharyngeal dysfunction. Although the pathophysiology of the diverticulum is not completely clear, it is apparent that incomplete or poorly timed cricopharyngeal relaxation plays a central role in its development and expansion. It is suggested that intrapharyngeal pressure with inadequate relaxation of the cricopharyngeus muscle leads to fibrosis of the muscle fibers over the area of increased pressure . Surgical treatment for Zenker’s diverticulum should be considered in patients who are symptomatic, because the sequelae may be life threatening: patients may have significant weight loss and be at risk of aspiration of the diverticulum contents. Additionally, dietary limitations may require lifestyle modifications and alter the patient’s quality of life, which may be improved with surgical treatment. If patients are asymptomatic, or if the diverticulum causes minimal symptoms, long-term monitoring may be considered in lieu of immediate surgical management.

Most of these patients have intact hypopharyngeal contraction forces, and in most cases the surgical intervention of cricopharyngeal myotomy, with or without removal of the diverticulum pouch, alleviates symptoms. Most patients who have Zenker’s diverticulum have a relatively obvious problem with severe symptoms. Because the surgery is simple and has a high probability of a positive outcome, the choice to proceed is straightforward. The trend in the United States has been toward using transoral approaches and to complete the myotomies with either laser techniques or endoscopic stapling. The outcomes are equally good with either approach, and the risks are the same, so either approach is justified . Open cricopharyngeal myotomy now is used primarily when neck anatomy and/or cervical spine stiffness prevent the placement of a necessary pharyngoscope.

The external approach to resection of a Zenker’s diverticulum involves a cervical neck incision with dissection to identify the diverticulum, which then is freed from the surrounding tissues. A cricopharyngeal myotomy is performed next, followed by excision, inversion, or suspension of the pouch using a suture or staple technique . This approach has a higher rate of complications, including fistulas, recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy, pneumomediastinum, and mediastinitis, and has been passed over for newer, safer endoscopic techniques. Compared with open surgery, endoscopic methods lead to a shorter postoperative course with very low rates of serious complications such as mediastinitis . Additionally, most patients report relief of symptoms after endoscopic surgery . Endoscopic techniques include an endoscopic staple diverticulostomy and a laser-assisted technique. This technique uses a modified bivalved laryngoscope to visualize the diverticulum. Division of the common wall between the diverticulum and the esophagus is performed with electrocautery, carbon dioxide laser, or staples, thereby performing an internal cricopharyngeal myotomy and creating a single lumen . Some controversy remains as to which endoscopic approach is best. Each has merits and limitations, but the published data show little or no significant difference in outcomes and risk ( Table 2 ).

| Type of cricopharyngeal myotomy | Advantages | Risks and disadvantages | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| External approach | Access to large diverticula | Fistula, recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy, mediastinitis | Effective, with a higher complication rate than endoscopic approaches |

| Endoscopic staple-assisted | Least operative time | Esophageal perforation, pneumomediastinum | 2.6% complication rate |

| Fastest return to oral diet | Cannot always be placed through scope or used for smaller diverticula | 0.3% mortality rate | |

| Shortest hospital stay | Produces an incomplete myotomy at the tip | 6% recurrence rate | |

| Endoscopic laser-assisted | Intermediate return to oral diet | Thermal tissue injury | 3%–8.1% complication rate |

| 0.2% mortality rate | |||

| Postoperative fever, pneumomediastinum, hemorrhage | 3 to 11.5% recurrence rate | ||

| Endoscopic cautery | Longest operative time | Thermal tissue injury, fistula, mediastinitis, hemorrhage | 7.4% complication rate |

| Longest return to oral diet | 0% mortality rate | ||

| 3.4% recurrence rate |

Zenker’s diverticulum

Zenker’s diverticulum ( Fig. 2 ) is within the spectrum of cricopharyngeal dysfunction. Although the pathophysiology of the diverticulum is not completely clear, it is apparent that incomplete or poorly timed cricopharyngeal relaxation plays a central role in its development and expansion. It is suggested that intrapharyngeal pressure with inadequate relaxation of the cricopharyngeus muscle leads to fibrosis of the muscle fibers over the area of increased pressure . Surgical treatment for Zenker’s diverticulum should be considered in patients who are symptomatic, because the sequelae may be life threatening: patients may have significant weight loss and be at risk of aspiration of the diverticulum contents. Additionally, dietary limitations may require lifestyle modifications and alter the patient’s quality of life, which may be improved with surgical treatment. If patients are asymptomatic, or if the diverticulum causes minimal symptoms, long-term monitoring may be considered in lieu of immediate surgical management.

Most of these patients have intact hypopharyngeal contraction forces, and in most cases the surgical intervention of cricopharyngeal myotomy, with or without removal of the diverticulum pouch, alleviates symptoms. Most patients who have Zenker’s diverticulum have a relatively obvious problem with severe symptoms. Because the surgery is simple and has a high probability of a positive outcome, the choice to proceed is straightforward. The trend in the United States has been toward using transoral approaches and to complete the myotomies with either laser techniques or endoscopic stapling. The outcomes are equally good with either approach, and the risks are the same, so either approach is justified . Open cricopharyngeal myotomy now is used primarily when neck anatomy and/or cervical spine stiffness prevent the placement of a necessary pharyngoscope.

The external approach to resection of a Zenker’s diverticulum involves a cervical neck incision with dissection to identify the diverticulum, which then is freed from the surrounding tissues. A cricopharyngeal myotomy is performed next, followed by excision, inversion, or suspension of the pouch using a suture or staple technique . This approach has a higher rate of complications, including fistulas, recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy, pneumomediastinum, and mediastinitis, and has been passed over for newer, safer endoscopic techniques. Compared with open surgery, endoscopic methods lead to a shorter postoperative course with very low rates of serious complications such as mediastinitis . Additionally, most patients report relief of symptoms after endoscopic surgery . Endoscopic techniques include an endoscopic staple diverticulostomy and a laser-assisted technique. This technique uses a modified bivalved laryngoscope to visualize the diverticulum. Division of the common wall between the diverticulum and the esophagus is performed with electrocautery, carbon dioxide laser, or staples, thereby performing an internal cricopharyngeal myotomy and creating a single lumen . Some controversy remains as to which endoscopic approach is best. Each has merits and limitations, but the published data show little or no significant difference in outcomes and risk ( Table 2 ).

| Type of cricopharyngeal myotomy | Advantages | Risks and disadvantages | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| External approach | Access to large diverticula | Fistula, recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy, mediastinitis | Effective, with a higher complication rate than endoscopic approaches |

| Endoscopic staple-assisted | Least operative time | Esophageal perforation, pneumomediastinum | 2.6% complication rate |

| Fastest return to oral diet | Cannot always be placed through scope or used for smaller diverticula | 0.3% mortality rate | |

| Shortest hospital stay | Produces an incomplete myotomy at the tip | 6% recurrence rate | |

| Endoscopic laser-assisted | Intermediate return to oral diet | Thermal tissue injury | 3%–8.1% complication rate |

| 0.2% mortality rate | |||

| Postoperative fever, pneumomediastinum, hemorrhage | 3 to 11.5% recurrence rate | ||

| Endoscopic cautery | Longest operative time | Thermal tissue injury, fistula, mediastinitis, hemorrhage | 7.4% complication rate |

| Longest return to oral diet | 0% mortality rate | ||

| 3.4% recurrence rate |

Glottic insufficiency

The larynx contains the glottis, which is the space between the true vocal folds and which has three primary functions: airway protection, respiration, and phonation . Glottal insufficiency is defined as the inability of the vocal folds to adduct fully and thus protect the lower airway during swallowing or voice production ( Fig. 3 A ).