Surgical Management of the Rotator Cuff Tendon-Deficient Arthritic Shoulder

Ori Safran

Ludwig Seebauer

Joseph P. Iannotti

INTRODUCTION

The arthritic shoulder with irreparable massive cuff deficiency is one of the most difficult and challenging issues in shoulder practice because of the combination of severe articular and periarticular soft-tissue damage. This entity is the common end-stage result of several disease processes such as rheumatoid arthritis, rotator cuff tear arthropathy, and Milwaukee shoulder syndrome. By creating a substantial defect in the rotator cuff tendons, these disease processes lead to destabilization of the glenohumeral joint with subsequent superior migration of the humeral head and secondary severe damage to both the intraarticular and extraarticular elements. The result is a painful, dysfunctional shoulder that necessitates, in many cases, a surgical solution to be carried out to decrease patient morbidity. The lack of adequate stability and the insufficient bone stock make the task of replacing the damaged joint with a stable construct a very difficult task. The aims of this chapter are to review the pathomechanics of this disorder, to evaluate the different treatment options, to discuss the indications for surgical treatment, to elaborate on the different surgical options, and to establish a decision-making

algorithm for the patient with a rotator cuff-deficient arthritic (RCDA) shoulder (Fig. 8-1).

algorithm for the patient with a rotator cuff-deficient arthritic (RCDA) shoulder (Fig. 8-1).

PATHOMECHANICS

The glenohumeral joint lacks significant intrinsic bony stability and thus relies to a great extent on its soft-tissue components. The rotator cuff tendons provide a major contribution to the dynamic stabilization of the glenohumeral joint by increasing the concavity-compression force in the joint (1, 2, 3, 4, 5). By their synchronous action, they oppose the displacing effect of the strong deltoid muscle, keeping the humeral head centered in the glenoid fossa throughout its movement (6, 7, 8). The coupled work of the infraspinatus and subscapularis has been shown to be a major factor in superior glenohumeral stability, whereas the contribution of supraspinatus is less significant (9,10). A massive tear, consisting of the supraspinatus and at least one of the other rotator cuff tendons (11) (in most cases the infraspinatus), may render the rotator cuff’s anterior and posterior force couple ineffective in both the vertical and the transverse planes. The result is a diminution of joint reaction force and a change in the overall direction of the joint force that leads to the destabilization of the glenohumeral joint (12). In cases where the long head of biceps is still functional, it may oppose, to some extent, to the superior migration of the humeral head (13,14).

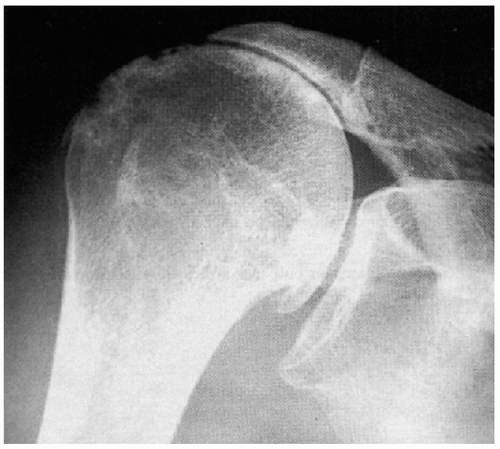

Once the proximal pull of the deltoid is left unopposed, the humeral head migrates superiorly toward the coracoacromial arch. The deltoid, which has lost its fulcrum, is left with a smaller mechanical advantage and therefore must generate more force to perform its function (15). The humeral head then articulates with the coracoacromial arch superiorly and the superior glenoid rim inferiorly, leading to flattening of the superior part of the humeral head and tuberosities (“femoralization”), rounding and thinning of the coracoacromial arch (“acetabularization”), and destruction of the superior glenoid region (Fig. 8-2). The acromioclavicular joint is also frequently involved in the process, joining its cavity with that of the now joined synovial intraarticular and subacromial bursal spaces. The end result is an incongruous, unstable joint with a higher joint friction and superiorly malpositioned center of rotation.

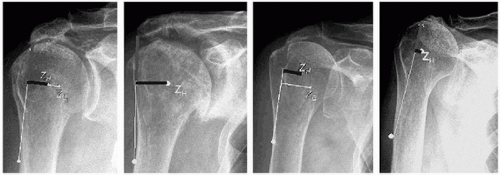

A pathomechanistic and pathomorphologic classification of RCDA, based on the position and stability of the humeral head, is presented in Fig. 8-3 (16). The classification is independent of the underlying pathologic conditions and is based on two critical issues for the function of the deltoid muscle: The glenohumeral center of rotation and the degree of anterior-superior instability.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Although sharing a common end result, it is important to recognize the various disease processes leading to glenohumeral RCDA joint.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is the most common cause of RCDA. Between 48% and 65% of patients with RA have significant glenohumeral joint involvement. Approximately 24% of those with glenohumeral arthritis will have a simultaneous rotator cuff tear (17,18). Superimposed on the aforementioned changes are severe osteopenia, erosions of the entire glenoid without osteophyte formation, and medialization of the glenohumeral joint.

Figure 8-3 Pathomechanical and pathomorphological classification of RCDA. Z=center of rotation, horizontal line represents the moment arm of the deltoid. |

Cuff tear arthropathy (CTA) is the extreme end result of a massive rotator cuff tear. The term coined by Neer in 1983 (19) refers to a primary massive rotator cuff tear that, by virtue of mechanical superior instability and nutritional effects, leads to a secondary glenohumeral joint destruction (21). It is believed that between 0% and 25% of massive rotator cuff tears will end up as CTA, but it is difficult, if not impossible, to predict which of the massive tears will result in CTA.

The Milwaukee shoulder syndrome was originally described by McCarty in 1981 (20). This is an uncommon entity affecting shoulders of elderly people, predominantly women. It consists of a massive rotator cuff tear, joint instability, bony destruction, and a large blood-stained joint effusion containing basic calcium phosphate crystals, detectable protease activity, and minimal inflammatory elements. Its relation to rotator cuff arthropathy is not clear, and it might represent one spectrum of the disease. The role of the basic calcium phosphate crystals in creating this syndrome is still controversial. Whether it is the cause of the articular damage, through macrophage spillage of proteases, or just the result of the osteoarthritic process is still unknown (21).

Primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis is the most common reason for shoulder joint replacement. However, it is associated with rotator cuff tear in only 5% of patients, most of which are reparable. It is therefore uncommon for primary osteoarthritis to end up as RCDA.

CLINICAL PICTURE

Patients with an arthritic shoulder and an irreparable, massive cuff deficiency are primarily elderly people, with female gender predominance. Their main complaints are of severe shoulder pain; limited range of movement; and, in some cases, recurrent swelling of the shoulder. The pain is constant, aggravated by shoulder motion, and felt at the periacromial region and the glenohumeral joint line. On physical examination the examiner can observe wasting of the infraspinatus and supraspinatus muscles, a decrease in active and passive glenohumeral motion, and crepitus while moving the patient’s shoulder (21). The x-ray image is typical and consists of a superiorly positioned humeral head, an “acetabularized” socket built up from a thinned, sclerotic acromion, and the eroded upper glenoid fossa (Fig. 8.2). Occasionally, the acromioclavicular joint and distal clavicle are also damaged and are thus included in the “socket.” Cases of secondary stress fractures of the thinned acromion have also been published (22).

The combination of the clinical and radiologic information is, in most cases, sufficient to make the proper diagnosis, although other modalities such as computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging may be needed for treatment planning.

TREATMENT

RCDA shoulder combines severe articular damage, bone destruction, osteoporosis, and rotator cuff tendon deficiency resulting in glenohumeral destabilization. In contrast to the more common primary degenerative shoulder arthrosis, the inherent instability of the rotator cuff-deficient shoulder necessitates specific consideration. Severe pain and shoulder dysfunction lead many of these patients to seek medical advice. The treatment armamentarium available is variable and includes both conservative, nonsurgical treatment and surgical procedures such as humeral head replacement, total shoulder arthroplasty, and even arthrodesis and resection arthroplasty. The responsibility of the orthopedic surgeon is to tailor the best treatment option for the particular patient, taking into account the patient’s symptoms, functional needs, and the bone and soft-tissue conditions of the shoulder joint.

TREATMENT OPTIONS

Conservative Nonsurgical

Patients with mild symptoms and mild limitation in functional range of motion and activities of daily living should be treated nonsurgically. Treatment includes the use of analgesics and physical therapy to maintain range of motion and to strengthen the deltoid muscle. It has been shown that by strengthening the middle one-third of the deltoid, some improvement with superior stability control can be gained (23). The use of repeated steroid injections is discouraged, but an occasional injection may be helpful in managing the most acute symptoms. In those patients with unremitting pain, significant motion-related pain, and limitation in range of motion and activities of daily living, surgical intervention should be considered.

Glenohumeral Arthrodesis and Resection Arthroplasty

The basic concept of fusion is to eradicate pain with elimination of motion. However, there are several drawbacks to its use in this condition.

Arthrodesis necessitates good function in the opposite shoulder. However, in as many as 40% of patients with RCTA and in even a higher percentage of patients with rheumatoid arthritis, the opposite shoulder is involved in a similar process. The involved shoulder is, in most cases, severely osteopenic and thus more prone to fixation failure and nonunion.

Increased scapulothoracic motion is needed after glenohumeral arthrodesis exposes the already damaged acromioclavicular joint to excessive motion and, therefore, pain.

Most of the patients involved are elderly patients. Elderly patients have difficulties submitting to the demanding postoperative rehabilitation process necessary after this arthrodesis (24).

Cofield and Briggs (25), in 1979, reported on 12 patients with rotator cuff tear arthropathy (average age 50 years) that had their shoulder fused. Two of 12 developed nonunion and six of 12 necessitated a second operation for acromioclavicular pain, nonunion, or proximal migration. It seems proper to apply the recommendations of Arntz and colleagues (26,27) to consider using arthrodesis in irreparable rotator cuff tears, only in combination with irreparable deficiencies of the deltoid muscle, or in the younger patient with demands for substantial strength at low angles of flexion.

Resection arthroplasty is a poor solution, which yields an unstable, nonfunctional, often painful shoulder and thus should not be carried out as a primary surgical treatment in these patients.

Constrained Total Shoulder Arthroplasty

The lack of joint stability led researchers and surgeons in the early 1970s and early 1980s to use constrained designs of total shoulder arthroplasty in cases of RCDA shoulder to create a steady fulcrum for deltoid action. Although initial

reports showed good clinical results, longer-term follow-up revealed a high percentage of glenoid component loosening and breakage of implants. Post and Jablon (28) reported that glenoid component radiolucent lines appeared in 30% of primary constrained arthroplasties used in RCDA shoulders. Lettin and colleagues (29) reported on 10 of 49 shoulders that developed relatively early glenoid component loosening. It appeared that the inherent constraints in the prosthesis transferred strong shear forces to the glenoid component-bone interface. The increased shear forces combined with the osteopenic nature of the bone and the small surface area of the interface led to the glenoid loosening. Giving the unacceptably high failure rates, the use of these types of fully constrained, fixed fulcrum, total shoulder constructs for rotator cuff deficient shoulders was abandoned by almost all surgeons.

reports showed good clinical results, longer-term follow-up revealed a high percentage of glenoid component loosening and breakage of implants. Post and Jablon (28) reported that glenoid component radiolucent lines appeared in 30% of primary constrained arthroplasties used in RCDA shoulders. Lettin and colleagues (29) reported on 10 of 49 shoulders that developed relatively early glenoid component loosening. It appeared that the inherent constraints in the prosthesis transferred strong shear forces to the glenoid component-bone interface. The increased shear forces combined with the osteopenic nature of the bone and the small surface area of the interface led to the glenoid loosening. Giving the unacceptably high failure rates, the use of these types of fully constrained, fixed fulcrum, total shoulder constructs for rotator cuff deficient shoulders was abandoned by almost all surgeons.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree