Surgical Management of Patellar Instability

Alex Dukas

Michael Pensak

Cory Edgar

Thomas DeBerardino

CLINICAL EVALUATION

Pertinent History

Predisposing anatomical factors and/or traumatic events are both common findings among patients who cite a history of multiple patella dislocations (1). A comprehensive history should focus on the onset and duration of symptoms, the mechanism of injury, provocative maneuvers/activities, and any prior patellofemoral joint symptoms. Patients with trochlear dysplasia or significant limb malalignment typically present at a very young age and have minimal history of trauma. In this patient, it is common to have failed past procedures and requires a meticulous workup to ensure successful outcome, as a single procedure is usually not enough. Patients who have recurrent dislocations frequently report diffuse pain around the knee that is aggravated by going up and down stairs or getting up from a seated position, as well as feelings of insecurity about their knee with episodes of giving way, crepitation, and/or swelling. If treatment was unsuccessful, it is necessary to determine whether it was in part due to a diagnostic error, inappropriateness of the treatment modality, issues with patient compliance or perhaps a new event that exacerbated the patient’s symptoms. It is important to delineate the difference between symptomatic instability and pain due to cartilage lesions, overload, or osteoarthritis.

Physical Exam

A focused physical exam should begin with adequate inspection of both lower extremities, preferably with the patient wearing shorts. The presence of an effusion and whether or not the patella is ballotable should be noted. Repetitive flexion/extension of the knee with the patient relaxed and the physician’s palm centered over the patella will help gauge if the patella tracks normally in the center of the trochlea. The presence of the “J sign” should be sought in which the patella subluxates from its centered position in the trochlea at 30° of flexion to a lateral position at full extension.

If the patient presents with acute subluxation, ballottement and effusion should be evaluated. Aspiration of joint fluid might reveal serosanguinous fluid. The presence of fat droplets may indicate the presence of osteochondral fragment(s) within the joint (2).

The Q-angle, defined as the angle formed between intersecting lines from the anterior superior iliac crest to the midpatella and from the midpatella to the midtibial tuberosity with the patient supine, should be measured. This angle provides an estimate of tibial and femoral torsion about the knee joint. Normal Q-angles are 14° and 17° for males and females, respectively. Angles greater than these can predispose patients to patellar instability. When making this measurement, it is critical to ensure that the patella is centered over the trochlear groove as slight subluxation owing to a deficient medial patellofemoral ligament (MPFL) or medial structures can falsely decrease the Q-angle.

The extent to which the patella glides medially and laterally can offer valuable information about the soft-tissue structures around the patella. The main static soft-tissue stabilizer of the patella is the MPFL, accommodating approximately 53% of patellar tension (3). Lesser contributions come from the medial patellar retinaculum. The integrity of the MPFL can be evaluated by assessing the extent of lateral patellar glide. This maneuver is performed with the patient supine, relaxed and the leg in extension. The examiner then shifts the patella laterally from the midline. Excursion of three quadrants or more indicates a hypermobile patella and possible damage to the MPFL and medial-sided structures (2). Failure of the patella to move more than quadrant in the medial direction suggests a tight lateral retinaculum.

Patellar tilt refers to the examiner’s ability to raise the lateral edge of the patella past the horizontal in the axial plane with the patient supine, relaxed and the knee flexed approximately 20°. Patients with tight lateral structures may have chronic overload of the lateral patellar facet and have tenderness to palpation along the lateral border of the patella upon physical exam (4).

The patellar apprehension test is an attempt to elicit the same sensations experienced by a patient who previously suffered a patella dislocation. With the patient supine, relaxed and the knee flexed 20° to 30°, the examiner

carefully glides the patella laterally looking for any quadriceps contraction, indicating a positive test for the apprehension sign.

carefully glides the patella laterally looking for any quadriceps contraction, indicating a positive test for the apprehension sign.

If crepitus is felt with patellar compression during full ROM, patellar arthrosis or chondral lesions should be suspected. Compression of the patella during full range of motion of the knee may reproduce the associated pain. Approximate location of cartilage lesions can be made on the basis that the distal chondral surface of the patella articulates with the femoral trochlea early in flexion and more distally as the knee is flexed. Posterior drawer stability should also be examined, as the presence of a PCL deficiency is associated with degenerative patellar arthritis (5). Valgus stability should also be assessed, as MCL injury is associated with MPFL tears (4).

IMAGING

Radiographs

A set of standard knee radiographs should be obtained consisting of weight-bearing posteroanterior (PA) views of both knees in extension and 45° of flexion, lateral views, and Merchant views. Aside from patella-specific measurements, all radiographs should be scrutinized for located joints (patellofemoral and tibiofemoral) and the presence of subtle fractures.

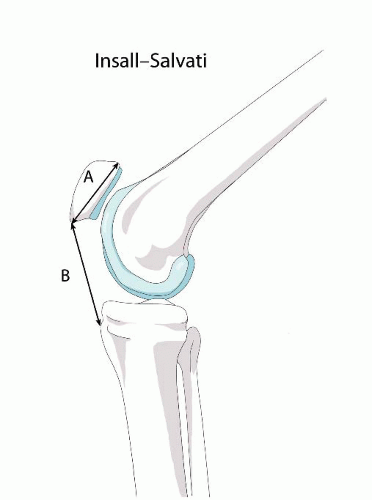

FIGURE 61.1. The Insall-Salvati index is calculated by dividing the length of the patellar tendon by the diagonal length of the patella. Normal values are within the range of 0.8 to 1.2. |

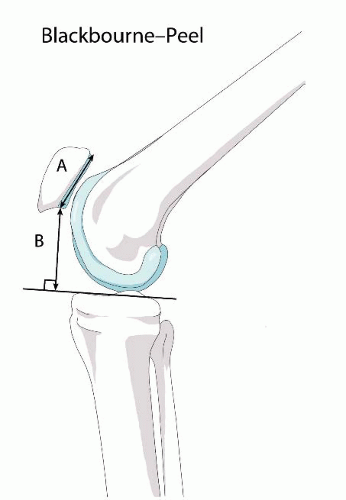

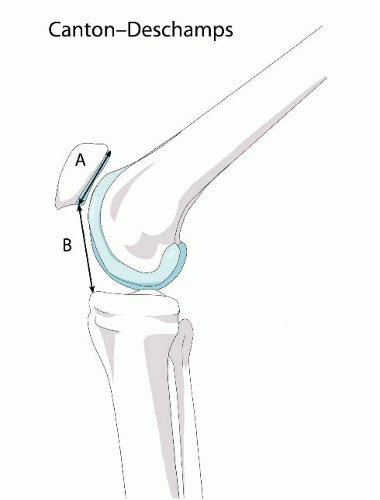

True lateral radiographs with the knee in 30° of flexion are of utmost importance in evaluation as assessment of trochlear dysplasia, tilt, and patellar height can be made from this view. Patellar height is valuable as an abnormally high patella, patella alta, has been implicated in 25% of patellar dislocations (6). Patella height can be measured by many methods namely, the Blackburne-Peel, Insall-Salvati, or Caton-Deschamps ratios (7) (Figs. 61.1, 61.2 and 61.3). The Insall-Salvati index is calculated by dividing the length of the patellar tendon by the diagonal length of the patella (B/A), normal being in the range of 0.8 to 1.2. The Blackburne-Peel index is calculated by measuring the perpendicular distance from the lower end of the articular surface of the patella to a line projected forward along the tibial plateau (the tibial plateau line) and then dividing that distance by the length of the articular surface of the patella (B/A), normal range being 0.54 to 1.06. The Caton-Deschamps index is calculated by measuring the distance between the lower end of the (spacing) articular surface of the patella and the designated superior anterior angle of the tibia and then dividing that distance by the length of the articular surface of the patella (B/A), normal range being 0.6 to 1.2. Escala et al. (8) reported a 78% sensitivity and 68% specificity when using the Insall-Salvati

ratio. However, it has been shown that the Blackburne-Peel is the most reproducible ratio and has been preferred in more recent literature (9, 10 and 11).

ratio. However, it has been shown that the Blackburne-Peel is the most reproducible ratio and has been preferred in more recent literature (9, 10 and 11).

Evidence of trochlear dysplasia has been implicated in up to 96% of patients with a true history of patellar dislocation (12). The degree of trochlear dysplasia can be gauged from the lateral radiograph by the presence of a supratrochlear spur, double contour (hypoplastic medial condyle), or crossing sign (floor of the trochlear groove crosses the anterior outline of the lateral femoral condyle). Evidence of patellar tilt can be seen if there is overlap of the medial condylar ridge and lateral patellar facet, but this is more definitively evaluated on axial views (13, 14).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree