Study Design and Outcome Measures in Osteoarthritis Clinical Trials

Vibeke Strand

Marc C. Hochberg

The typical patient with osteoarthritis (OA) is middle-aged or elderly and presents with the gradual onset of pain and stiffness accompanied by loss of function. Pain, gradual or insidious in onset, is usually moderate in intensity, worsened by use of involved joints, and improved or relieved with rest. Whereas pain at rest and nocturnal pain are thought to be features of severe disease, they may be indicative of both local inflammation and raised intraosseous pressure in the juxta-articular bone. The mechanism of pain in patients with OA is multifactorial. Pain may result from periosteal proliferation at sites of bone remodeling; subchondral microfractures; capsular irritation from osteophytes; periarticular muscle spasm; bone angina due to decreased blood flow and elevated intraosseous pressure; and synovial inflammation accompanied by the release of prostaglandins, leukotrienes, and various cytokines, including interleukin-1.1 Morning stiffness and gel phenomenon, or stiffness after periods of rest and inactivity, are also common and usually resolve within 30 minutes and several minutes, respectively. Loss of function resulting from pain and other symptoms of OA may involve both activities of daily living, such as bathing, dressing, feeding, grooming, and toileting, and instrumental activities of daily living, and lead to a reduction in the patient’s quality of life.2,3 Indeed, recent work using the model of disablement developed by the Institute of Medicine shows that pain is the major determinant of physical disability, whereas physical disability is the major determinant of reduced quality of life in patients with OA.4,5 Furthermore, pain is a predictor of both radiographic progression and need for total joint replacement in patients with OA.6 Hence, contemporary management of OA is primarily focused on amelioration of pain and physical limitations; future treatment opportunities are likely to include slowing or arresting of the progression of the underlying disease.7

To determine whether new treatments for symptom and structure modification are effective, properly designed and conducted randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are necessary. This chapter reviews the design and conduct of clinical trials in patients with OA and the types of outcome measures used in these trials. Regulatory issues regarding registration of new therapies for OA in Europe and the United States are highlighted.

Design Of Clinical Trials In Osteoarthritis

Issues in the design of RCTs in patients with OA and limitations of published trials were discussed more than 20 years ago by Altman and Hochberg.8 In 1996, the Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI) produced recommendations for the design and conduct of clinical trials in patients with OA.9,10 Outcome Measures in Rheumatology

Clinical Trials (OMERACT), an international consensus effort initiated in 1992, strives to improve outcome measures through a data driven, iterative consensus process of expert polls, committee discussion, literature review, validation studies, and data mining. In 2003, a joint effort sponsored by OARSI, OMERACT, representatives of regulatory agencies such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and the pharmaceutical industry established the OARSI Standing Committee for Clinical Trials Response Criteria Initiative to produce a set of responder criteria to treatment in the three symptomatic domains: pain, function, and patient global assessment.11,12 The concept of classification by symptom and structure modification is derived from a committee of the World Health Organization and International League of Associations of Rheumatology.13

Clinical Trials (OMERACT), an international consensus effort initiated in 1992, strives to improve outcome measures through a data driven, iterative consensus process of expert polls, committee discussion, literature review, validation studies, and data mining. In 2003, a joint effort sponsored by OARSI, OMERACT, representatives of regulatory agencies such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and the pharmaceutical industry established the OARSI Standing Committee for Clinical Trials Response Criteria Initiative to produce a set of responder criteria to treatment in the three symptomatic domains: pain, function, and patient global assessment.11,12 The concept of classification by symptom and structure modification is derived from a committee of the World Health Organization and International League of Associations of Rheumatology.13

Study Population

Selection of subjects relies not only on diagnostic criteria but also on identification of prognostic factors, which may predict responsiveness of the patient population to the therapeutic intervention being tested. Ideally, participants should fulfill validated criteria for the classification of symptomatic OA, such as those published by the American College of Rheumatology.14,15,16 In addition, trials of symptom-modifying agents should include patients whose disease is likely to respond to treatment, for example, those with pain of at least moderate intensity. Trials of structure-modifying agents should include patients without end-stage disease; furthermore, these types of studies should strive to include patients at high risk of structural progression, for example, middle-aged overweight women with unilateral knee OA17 or patients with an increased uptake on bone scintigraphy in the juxta-articular bone.18 The role of serum levels of biochemical markers of bone and cartilage turnover as a predictor of structural progression in patients with symptomatic OA remains under investigation and is the subject of an ongoing multidisciplinary initiative coordinated by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (http://www.niams.nih.gov.easyaccess1.lib.cuhk.edu.hk/ne/oi/oabiomarwhipap.htm).

Study Joints

Which joints in patients with OA should be studied? In general, for studies of symptom-modifying agents, trials should focus on disease in the symptomatic or index joint; data on symptoms in other joints that may also be affected as part of a generalized osteoarthritic process should also be collected. For studies of structure-modifying agents, trials should also focus on the index joint; herein, data on both symptoms and structural change should also be collected for other affected joints. These additional data should be considered secondary outcomes when data on the index joint are the primary outcome measures.

Duration of Trials

Trial duration for demonstration of symptom improvement should be at least three months; product- or device-specific considerations (e.g., new classes of agents, agents with delayed onset) may lengthen the duration. Current recommendations stress that RCTs of symptom-modifying drugs should be at least 6 months in duration “to assess the maintenance of the therapeutic effect” and continued up to 1 year for collection of data on adverse events and to establish that the drug does not have a deleterious effect on cartilage.9 Trials of structure-modifying agents should be of 1 to 2 years duration.13

Outcome Measures

Outcome measures in OA assess three primary domains: clinical, structural, and biochemical.9 OMERACT 3 focused on the development of consensus recommendations for outcome measures to be used in clinical trials in OA; participants concluded that a core set should include those measures, with greater than 90% of individuals voting for inclusion, those items for which greater than 25% of individuals voted should be strongly recommended, and the remaining outcomes could be optional.19 The final core set items, listed in Table 18-1, were pain, physical function, patient global assessment, and, for studies of at least 1 year in duration, joint imaging.11,20 At OMERACT 6, meeting participants voted to ratify the OMERACT-OARSI set of criteria. It was subsequently found that successful trial designs must include both absolute and relative change, as well as measures of pain and function as primary domains.12

TABLE 18-1 PROPORTION OF PARTICIPANTS VOTING FOR INCLUSION OF SPECIFIC OUTCOME DOMAINS IN THE CORE SET FOR PHASE III TRIALS IN PATIENTS WITH OSTEOARTHRITIS OF THE HAND, HIP, AND KNEE, OMERACT III (APRIL 1996) | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

Studies of Symptom Modification

Disease-Specific Measures

As pain is the most important symptom of OA, measurement of pain and its improvement with therapy is often the primary outcome variable in RCTs of symptom-modifying therapy. In 1981, Bellamy undertook the development of an evaluative index, the Western Ontario and McMaster

Universities (WOMAC) OA Index, using self-report to assess specifically OA of the knee and hip.20,21,22 The conceptual basis of the index, derivation of the item inventory, and results of validation studies have been described extensively elsewhere and are only briefly reviewed here.23 Questionnaire items were selected according to responses from 100 patients with OA on the basis of their prevalence, frequency, and importance to the patient. The final WOMAC includes a total of 24 questions divided into three sections: pain (five questions), stiffness (two questions), and function (seventeen questions) (Table 18-2). The questions probe symptoms of, and clinically important events affected by, lower limb OA and are answered by use of either a 5-point Likert scale or a 10-cm VAS. An eight-item short form of the WOMAC has been validated to enhance efficiency of use in RCTs and clinical practice.24 The WOMAC has been translated into most European languages and has been shown to be valid, reliable, and responsive in studies of patients undergoing total joint arthroplasty and in clinical trials of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and traditional Chinese acupuncture.25,26,27,28 Although results have been reported on the basis of a single question in the pain section, such as pain with walking on a flat surface, and as a total WOMAC score summing the three subscales, the use of domain-specific scores, especially for pain and function, is preferable.

Universities (WOMAC) OA Index, using self-report to assess specifically OA of the knee and hip.20,21,22 The conceptual basis of the index, derivation of the item inventory, and results of validation studies have been described extensively elsewhere and are only briefly reviewed here.23 Questionnaire items were selected according to responses from 100 patients with OA on the basis of their prevalence, frequency, and importance to the patient. The final WOMAC includes a total of 24 questions divided into three sections: pain (five questions), stiffness (two questions), and function (seventeen questions) (Table 18-2). The questions probe symptoms of, and clinically important events affected by, lower limb OA and are answered by use of either a 5-point Likert scale or a 10-cm VAS. An eight-item short form of the WOMAC has been validated to enhance efficiency of use in RCTs and clinical practice.24 The WOMAC has been translated into most European languages and has been shown to be valid, reliable, and responsive in studies of patients undergoing total joint arthroplasty and in clinical trials of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and traditional Chinese acupuncture.25,26,27,28 Although results have been reported on the basis of a single question in the pain section, such as pain with walking on a flat surface, and as a total WOMAC score summing the three subscales, the use of domain-specific scores, especially for pain and function, is preferable.

TABLE 18-2 ITEMS IN THE WOMAC OSTEOARTHRITIS INDEX | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Creamer and colleagues29 examined the relationship between the pain subscale of the WOMAC OA index, the McGill Pain Questionnaire, and a single 10-cm VAS pain-rating scale in 68 outpatients with OA of the knee. Although all three scales correlated with one another, the strongest correlation was between the WOMAC pain scale and the single 10-cm VAS pain scale. Severity of anxiety, depression, and fatigue all showed significant modest correlation with the McGill pain score, whereas none significantly correlated with the WOMAC pain score. On the other hand, total osteophyte score combining the tibiofemoral and patellofemoral joints correlated significantly with the WOMAC pain score but not with the McGill pain score. Largely on the basis of these findings, the authors concluded that the WOMAC pain scale should be the preferred measure of pain in clinical studies of patients with knee OA.

In the early 1980s, Lequesne and colleagues30 developed two indices for measurement of severity of OA of the hip and knee that combine three domains: pain or discomfort (five questions), maximal distance walked, and activities of daily living (four items). These instruments were recommended as outcome measures for OA trials in the 1985 guidelines for antirheumatic drug research promulgated by the European League of Associations of Rheumatology.31 The indices for knee and hip differ with regard to only one of the five pain items and in the four activities of daily living (Table 18-3). This instrument has been shown to be valid, reliable, and responsive in clinical trials of NSAIDs, slow-acting symptom-modifying drugs such as diacerein, and intra-articular agents and with traditional Chinese

acupuncture.32,33,34 The relative statistical efficiency of the WOMAC is similar to that of the Lequesne indices, although the WOMAC subscales and global score may be slightly more responsive than the comparable Lequesne sections and index.35

acupuncture.32,33,34 The relative statistical efficiency of the WOMAC is similar to that of the Lequesne indices, although the WOMAC subscales and global score may be slightly more responsive than the comparable Lequesne sections and index.35

TABLE 18-3 ITEMS IN THE LEQUESNE ALGOFUNCTIONAL INDICES FOR OSTEOARTHRITIS | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

Several instruments have been developed and validated to evaluate hand OA: the Dreiser Functional Index for Hand Osteoarthritis,36 the Australian/Canadian (AUSCAN) OA Hand Index modeled after the WOMAC OA index,37,38 the Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand (DASH) questionnaire,39 and the Cochin Index.40 There is limited experience with their use. While all have been shown to be reliable, valid, and responsive to change in RCTs, there are no published data comparing their performance in the same study. Recommendations for the conduct of clinical trials in the hand, recently been published by the Osteoarthritis Research society International (OARSI), represent a significant addition to methodologic study approaches for this region of OA.40a

The Stanford Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ), a self-report questionnaire, has been used in clinical trials in rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and progressive systemic sclerosis in addition to OA. The disability index contains 20 questions to assess eight categories of physical function (dressing and grooming, arising, eating, walking, hygiene, reach, grip, and activities); each question is scored by patients from 0 (without difficulty) to 3 (unable to do).41 The worst scores in each category are then summed and divided by the number of categories to give the disability index. It has been extensively translated and shown to be valid, reliable, and responsive in clinical trials. In a comparative study of patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty, the WOMAC was slightly more responsive than the HAQ disability index.42 The HAQ disability index should be especially useful in assessing treatment of patients with generalized OA because the range of activities captures both upper and lower extremity function. A shorter version of the HAQ disability index, the modified Health Assessment Questionnaire (MHAQ), is available as a single page of eight questions about functional activities performed on a daily basis; these are derived from the HAQ and are scored by patients from 0 (without difficulty) to 3 (unable to do).43 The MHAQ has been shown to have responsiveness similar to that of the WOMAC OA Index.44

The Arthritis Impact Measurement Scale (AIMS), and the newer AIMS2, are comprehensive self-report questionnaires designed to evaluate mobility, physical activity, dexterity, social role, social activity, activities of daily living, pain, depression, and anxiety.45,46 They are valid and reliable; however, their use has been limited in part because of the time required for completion and scoring. Like the HAQ disability index, the AIMS is slightly less responsive than the WOMAC in OA patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty.42 It would also be a useful instrument in assessing treatment of patients with generalized OA.

Patient Global Assessment

The third element in the recommended core set of outcomes is patient global assessment of disease activity. The standard question, “Considering all of the ways your arthritis affects you, how are you doing today?” utilizes either a 5-point Likert scale (very good, good, fair, poor, very poor) or a 10-cm VAS.47 Physician global assessment of disease activity is a subjective judgment queried as: “How would you describe the patient’s disease activity today?” scored by a 5-point Likert scale (none, mild, moderate, severe, very severe) or 10-cm VAS. The clinimetric properties of both measures have been described by Bellamy.21

Health-Related Quality of Life Measures

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) focuses on aspects of life that are directly affected by a health condition: physical, social/psychological functioning, work functioning, and vitality, but not personal values, socioeconomic status, environment, opportunity, or social network.48 The Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) is a generic instrument designed to measure HRQoL with scores based on responses to individual questions, summarized into eight domains: physical functioning, role-physical, body pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role-emotional, and mental health.49,50 These eight domains are also combined into summary physical and mental component scores, again scored from 0 to 100; higher scores reflect better HRQoL. The SF-36 has been extensively translated, and normative data are available for a broad variety of cultural and disease-specific populations. It has been used in clinical trials in rheumatoid arthritis, OA, psoriatic arthritis, and systemic lupus erythematosus and shown responsive to change after 4 to 6 weeks of treatment.51,52

The European Quality of Life Questionnaire (EuroQOL), now named the EQ5D, is another generic measure of HRQoL. This instrument assesses five domains of health status: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain and discomfort, and anxiety/depression; these are ranked from no problem to moderate to extreme difficulty, generating a potential 243 distinct health states.53 It includes a feeling thermometer asking patients to rate their own health status from 0 to 100.

The Work Limitations Questionnaire was designed by Lerner et al. in 2001 to measure the impact of health problems on the daily work of people with chronic disease. The questionnaire uses 25 items to identify four domains (time, physical, mental-interpersonal, and output demands), and uses a demand-level methodology to address job content. It has been validated, although not yet published in RCTs.54,55

Utilizing both generic and disease or rheumatology-specific measures allow a more complete assessment of a therapeutic intervention. Specifically, generic HRQoL instruments facilitate economic analyses of new therapies, across differing disease states and afford a societal perspective.

Studies of Structure Modification

Agents that may retard, arrest, or reverse the degenerative process of OA in human cartilage have been defined as disease-modifying OA drugs (DMOADs).13 To date, no

therapeutic agent has met this definition, and it remains unclear how best to identify this benefit, whether by radiographs, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or direct visualization using arthroscopy.

therapeutic agent has met this definition, and it remains unclear how best to identify this benefit, whether by radiographs, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or direct visualization using arthroscopy.

Radiography

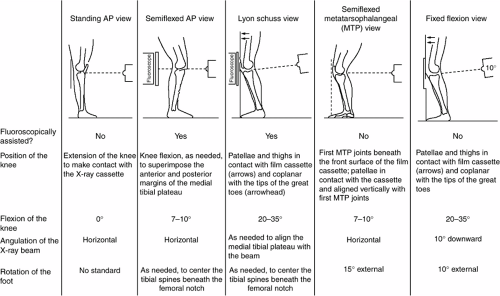

Although radiographs cannot directly visualize articular cartilage, several techniques have been developed to assess loss of joint space width (JSW). (Note: The term JSW is utilized here to distinguish it from “increased” joint space narrowing in RA, due to causes in addition to loss of articular cartilage.) To date, assessment of interbone distance using a plain radiograph of hip or knee remains the only validated measure of loss of JSW recommended for use in RCTs in OA, although the methodologic limitations are well recognized (Fig. 18-1).56,57,58

Specific weight-bearing methods to identify changes in JSW over time are valid only when the relevant articular surfaces remain in direct contact and are consistently assessed over time. It is challenging to reproducibly and precisely measure loss of JSW: 1) changes over time are small, on the order of 0.03 to 0.6 millimeters per year, and typically occur in only a subset of patients; 2) loss of JSW is often difficult to predict, as is the subset of “rapid progressors”; 3) identification of such a subset is dependent on the population accrued into the clinical trial; 4) conventional weight-bearing radiographs of hip and knee in full extension are poorly reproducible, especially in the knee (only one structural progression RCT has been conducted in hip OA); 5) varying degrees of flexion which inadvertently and all too frequently occur with repeated examinations of either joint may alter JSW width—in the absence of structural changes; and 6) intra-articular sites where deterioration most likely may occur expectedly differ across individuals.

Variability in assessment of JSW has been attributed to measurement techniques as well as heterogeneity across studied protocol populations. Simpler solutions, such as increasing sample sizes in RCTs of 2 to 3 years duration, or selecting treatment populations enriched for “risk factors” predicting progression, to overcome this high variability have so far proved impractical and prohibitively costly.59,60,61,62

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree