Abstract

Most studies of functional outcomes in hemiplegic stroke patients use standard disability rating scales (such as the Barthel Index). However, planning the allocation of assistance and resources requires additional information about these patients’ expectations and needs.

Aims of the study

To assess functional independence in daily living and house holding, changes in home settings, type of technical aid and human helps, and expectations in hemiplegic patients 1 to 2 years after the stroke.

Methods

Sixty-one out of 94 patients admitted to the neurovascular unit of French university hospital for a first-ever documented stroke were consecutively enrolled. The study was restricted to patients under 75, since patients over 75 do not follow the same care network. Patients were examined at their homes or interviewed by phone 17 months (on average) after the stroke. Standard functional assessment tools (such as the Barthel Index and the instrumental activities of daily living [IADL] score) were recorded, along with descriptions of home settings and instrumental and human help. Lastly, patients and caregivers were asked to state their expectations and needs.

Results

Although only one person was living in a nursing home after the stroke, 23 (34%) of the other interviewees had needed to make home adjustments or move home. Seven patients (11%) were dependent in terms of the activities of daily living (a Barthel Index below 60) and 11 (18%) had difficulty in maintaining domestic activities and community living (an IADL score over 10). Although the remaining patients had made a good functional recovery, 23 were using technical aids and 28 needed family or caregiver assistance, including 23 patients with full functional independence scores. Twenty-five patients (42%) were suffering from depression as defined by the diagnosis and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th edition, text revision, DSM IV-R). The patients’ prime concerns were related to recovery of independence, leisure activities and financial resources. Family members’ expectations related to the complexity of administrative matters, lack of information and the delay in service delivery.

Discussion and conclusion

In under-75 hemiplegic stroke patients, high scores on standard disability rating scales do not always mean that no help is required.

Résumé

De très nombreuses études ont évalué le devenir fonctionnel après accident vasculaire cérébral (AVC) à l’aide d’échelles fonctionnelles, mais il est nécessaire pour planifier les aides et les ressources à mettre en œuvre de disposer aussi de données détaillées sur les conditions de vie, les besoins d’aide et les attentes de ces patients à distance de l’AVC.

Objectifs

Évaluer chez des patients victimes d’AVC constitué l’autonomie, les aménagements du domicile, les soins de rééducation, les aides techniques et les aides humaines nécessaires et recueillir leurs attentes un à deux ans après l’attaque.

Matériel et méthodes

Soixante-et-un patients parmi 94 hospitalisés de façon consécutive pour un premier AVC en unité de neurologie spécialisée ont été revus ou interrogés par téléphone 17 mois en moyenne après l’attaque cérébrale. Nous avons limité l’étude aux patients âgés de moins de 75 ans, car dans notre ville les patients d’âge supérieur font l’objet d’une filière différente, spécifique, de réadaptation gériatrique. Le recueil des données comportait les documents habituels à cette pathologie : index de Barthel, activités instrumentales de la vie courante (IADL) de Lawton, ainsi qu’un relevé des aménagements matériels et des aides utilisées.

Résultats

Une seule patiente a été institutionnalisée. Tous les autres patients vivaient à domicile, mais 23 (34 %) avaient procédé à des aménagements, ou avaient déménagé. Sept patients (11 %) n’étaient pas autonomes dans la vie quotidienne et 11 présentaient des difficultés pour les actes élaborés de la vie domestique et sociale. La récupération fonctionnelle des autres sujets paraissait globalement bonne : 82 % des patients présentaient un index de Barthel supérieur ou égal à 90 et 64 % un IADL à 4. Un état dépressif selon les critères diagnosis and statistical manual (DSM IV-R) était retrouvé chez 25 patients (41 %). En analyse univariée, le besoin d’aide était indépendant de l’âge et du sexe, il était corrélé à l’index de Barthel, au score IADL de Lawton et à la présence d’une dépression. Cependant, 23 patients utilisaient une ou plusieurs aides techniques et 28 faisaient appel à une aide humaine, dont 23 patients dont l’autonomie était pourtant jugée complète. Les attentes principales des patients concernaient la diminution de l’autonomie et des loisirs, et les préoccupations financières. Les attentes principales des familles concernaient les délais d’attente, la complexité des démarches administratives ainsi que le manque d’information ressenti par rapport aux aides possibles.

Discussion et conclusion

Les échelles fonctionnelles évaluant l’autonomie dans la vie quotidienne sont utiles pour faire de la prédiction générale du devenir des AVC, mais insuffisantes pour évaluer les besoins d’aide, qui sont parfois plus élevés que le degré d’autonomie ne le laissait prévoir.

1

English version

In France, around 120,000 people per year suffer a stroke. The 1-year mortality has been estimated at between 10 and 12% – meaning that stroke corresponds to the third-ranked cause of death in industrialized countries . Fifty percent of stroke survivors will become depressed in the following year and 25% will develop dementia. Stroke thus represents the leading cause of acquired activity limitation in adult populations . This pathology also raises major public health issues due to its incidence and mortality, post-stroke dependency and psychological after-effects for the both patient and his/her close relations. This in turn leads to significant social costs (estimated at 27.5 billion euros in France in 2002, i.e. 1.81% of the country’s gross domestic product).

Post-stroke functional outcome is thus a subject of concern not only for stakeholders involved in acute neurological care and rehabilitation but also for decision-makers having to plan and allocate medical and social assistance and resources. Although many predictive studies have focused on this subject, most limited the follow-up period to a year at most and employed with activity limitation scales that have been validated in this domain: the Barthel index and/or the functional independence measure (FIM) . For example, Tilling et al.’s 2001 study examined functional recovery at 1 year for patients aged 70 on average; bladder dysfunction, dysarthria, female gender and handicap before stroke were found to be predictive of poor outcomes . In 2007, San Segundo et al. reported on a predictive model for delay in discharge with seven variables: social isolation, an FIM score below 50, age over 75, left hemiparesis, architectural barriers, a history of cardiovascular disease and male gender . In 2004, one of the authors of the present article studied the predictive factors for discharge to home and the functional outcome at 1 year in 156 subjects having suffered a first-ever hemispheric stroke . The mean patient age was 72 and 29% were over 80. In this study, early independent predictive factors of poor functional recovery were a low Barthel index on Day 2, a poor increase in the Barthel index between Day 2 and Day 15, the presence of executive disorders and, lastly, invalidating neurological disease prior to the stroke. The improvement in the Barthel index between Day 2 and 1 year was lower for older patients with bladder dysfunction. Lastly, the most predictive initial factors for discharge to home were the ischemic nature of the stroke, a high Barthel index on Day 15, the absence of incontinence and neglect on Day 15 and not living alone.

One key question is whether the information supplied by this type of activity limitation scale is sufficient to plan the required help and resources in a post-stroke care network. Is it also necessary to have detailed data on the patent’s living conditions, requirements for technical and human help and expectations? Although most of the functional recovery arises during the first 3 months, a follow-up period of at least a year provides better insight into the care network as a whole (including patients who have changed from one network to another) as well as home layouts, the implementation of assistance and the physical and mental adaptation (for the patient and his/her relatives) to these new living conditions.

The objective of the present study was to assess patient independence, home modifications, rehabilitation care, technical aids and human help that facilitated home living under the best possible conditions 1 to 2 years after a first-ever stroke. We limited our study to patients under the age of 75 because older patients in our city are handled by a specific geriatric rehabilitation care network (organized by one of the present authors) .

1.1

Material and methods

This retrospective, single-centre study did not have a control group. A questionnaire-based survey was performed either after examination of the patient at home or by telephone.

1.1.1

Population

We examined the personal medical files of all patients with an initial diagnosis of stroke hospitalised in the Neurology Service at Bordeaux University Hospital between October 2003 and April 2004.

1.1.2

Inclusion criteria

Stroke was defined by reference to the WHO criteria. Patients aged between 40 and 75 with CT- or MRI-confirmed brain hemispheric or cerebellar infarction or intracerebral haemorrhage were included. Only subjects affected by a first-ever stroke were considered.

1.1.3

Exclusion criteria

Patients who died during emergency care (i.e. prior to admission to the stroke unit) were excluded from this study. The other exclusion criteria were a transient ischemic attack, a subarachnoid haemorrhage, multiple stroke, patients living outside the Gironde county and patients having made a full neurological recovery at the time of stroke unit discharge.

1.1.4

Procedure

The investigating physicians did not participate in the patients’ medical care or follow-up, which were carried out in the usual way. Data was collected between October 2004 and July 2005, i.e. 12 to 24 months after the stroke (mean: 13.7 months). Once the family doctor has been informed, a letter presenting the survey and its objectives and a consent form were sent to the patients. Data concerning the stroke, the patient’s demographic information and contact details and the family doctor’s contact details were obtained from the medical files. All other information was obtained by interviewing the patient and his/her family. The questionnaire was administered at home for partially independent patients and by telephone for those who had achieved maximum independence in daily living (according to their family doctor).

1.1.5

Data gathered

Activity limitations and functional disabilities in activities of daily living were estimated using the Barthel index and the IADL score . The diagnosis and statistical manual (DSM IV-R) criteria were used to diagnose depression.

Rehabilitation care (speech therapy, occupational therapy and physiotherapy), home environments, technical aids and human helps were all addressed.

Lastly, the patients were asked to say whether they had increased, decreased or maintained the level of leisure activities performed at home and outside the home with their family and, in particular, social leisure activities (those performed with persons outside the family circle).

1.1.6

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS software, version 9.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Mann–Whitney and Kruskal–Wallis tests were used to compare independent quantitative data and the Chi 2 test was used for qualitative data. The significance threshold in all tests was set to p = 0.05. The Spearman rank test was also used for the correlation analysis.

1.2

Results

Following application of the exclusion criteria, 94 patients were included from October 2003 to April 2004. In this group, five patients died before data could be collected, 22 were lost to follow-up after having moved out of the area, two refused to take part in the study after explanation of its goals and the family doctors of four patients refused to take part in the study. Sixty-one patients were thus analyzed. Thirty-one were seen at home (in the presence or absence of a caregiver or close relative) and 30 were contacted by telephone.

The patients’ main characteristics are summarized in Tables 1, 2a and 2b . The mean ± standard deviation age was 64 ± 8.5 at the time of the study, with a non-Gaussian distribution. As expected, ischemic stroke largely prevailed. On discharge from the Neurology Service, 23 patients (34%) still displayed hemiplegia and/or aphasia and 26 (42%) were discharged into a physical and rehabilitation medicine (PRM) unit.

| Value | |

|---|---|

| Mean (S.D.) age | 64 (8.5) |

| Patients under 55 years | 9 (14.7%) |

| Men | 42 (68.8%) |

| Married or living as a couple | 43 (70.5%) |

| At least one dependent children | 8 (1.3%) |

| At least one child in residence | 10 (1.6%) |

| Living alone at home | 16 (26.2%) |

| Home setting | |

| Rural area | 30 (49%) |

| Semi-urban area | 3 (4.4%) |

| Urban area | 28 (46.6%) |

| Individual house a | 25/31 (80.6%) |

| Having a job at the time of stroke | 13 (21.3%) |

| Walking outside | |

| None | 2 (3.3%) |

| Less once by week | 1 (1.6%) |

| Less once by day | 10 (16.4%) |

| Every day | 46 (75.4%) |

a This data was collected only among 31 patients visited in there home setting.

| Ischemic stroke | 51 (83.6%) |

| Anterior cerebral artery infarct | 2 (3.3%) |

| Right and left middle cerebral artery infarct | 28 (45.9%) |

| Posterior cerebral artery infarct | 11 (18%) |

| Lacunar infarct | 10 (1.6%) |

| Haemorrhagic stroke | 10 (1.6%) |

| Hemiplegia Right side hemiplegia | 23 (34.4%) 14 |

| Aphasia | 23 (34,4%) |

| Initial stay in reanimation | 4 (6.6%) |

| Length of stay in acute ward (reanimation + neurology) | 21 days (S.D. 20.9) |

| Discharge toward rehabilitation unit | 26 (42.6%) |

| Length of stay in rehabilitation unit | 89.6 days (S.D. 58.8) |

| Discharge toward an other post acute unit than rehabilitation | 3 (4.9%) |

| Length of stay in an other post acute unit than rehabilitation | 50 days |

| Discharge toward nursing home | 1 (1.6%) |

| Removal from a family member | 2 (3.3%) |

| Removal | 3 (4.9%) |

| Return in the former residence | 55 (90.2%) |

| Need for instrumental device(s) or human help(s) or for both | 33 (54.1%) |

| Then return to home with or without instrumental device and/or home adaptation | Then removal from family member 2 (3.3%) | Then removal in a more accessible home 3 (4.9%) | Then discharged toward nursing home 1 (1.6%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stay in neurology alone | 28 (45.9%) | 1 (1.6%) | 0 | 1 (1.6%) |

| Discharge toward PRM | 20 (32.8%) | 1 (1.6%) | 3 (4.9%) | 0 |

| Discharge toward another post acute unit than PRM | 2 (3.3%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Stay in neurology then in family home | 3 (4.9%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Stay in neurology then in PRM then in family home | 1 (1.6%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Stay in neurology then in PRM then in an other post acute unit | 1 (1.6%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Neurological impairments and activity limitations on the day of the interview are summarized in Table 3 . Only one patient was discharged to a nursing home. All other patients returned home. Eight patients (13%) needed help with activities of daily living (Barthel index ≤ 60) and 18% had difficulty in maintaining domestic activities and community living (IADL over 10). The overall functional recovery of the other patients appeared to be good, since 82% had a Barthel index of 90 or over and 63.9% had an IADL score of 4. Of the 30 patients interviewed by telephone (because their family doctor considered that a full recovery had been made), only one patient had Barthel index of 90; the 29 others even had a Barthel index of 100 and all but two had a score IADL of 4. The recovery of gait also appeared to be good, with 53 patients (87%) being able to walk unassisted. There was a significant relationship between the Barthel index at 17 months on one hand and the length of stay in the acute ward ( R = 25.2, p < 0.005) and the IADL score ( ρ = −0.68, p < 0.001) on the other.

| Barthel index ( n = 61) | |

| Number of patients with score | |

| <30 | 2 (3.2%) |

| 30–60 | 6 (10%) |

| > 60 | 53 (86.8%) |

| IADL | |

| 4 | 39 (63.9%) |

| 5–9 | 11 (18%) |

| 10–14 | 10 (16.4%) |

| 15 | 1 (1.6%) |

| Depression (DSM IV-R) | 25 (41%) |

| Reduction in leisure | 37 (60.7%) |

| Driving a car | |

| Car adaptation | 3 (4.9%) |

| Stop driving | 22 (36.1%) |

The need to modify home fittings and layout and the requirement for technical aids and human help were greater than suggested by the Barthel index and IADL score ( Table 4 ). Thirty-one patients (50.8%) lived in rural areas, 27 (46.6%) lived in urban areas and three (4.4%) in semi-urban areas. Twenty-four of the 31 patients visited at home lived in a house (with an upper floor in 13 cases) and five lived in an apartment. Even though 29 were able to access all rooms in their home, 18 patients (26.5% of the total sample) had modified the home and its fittings and five (7.4%) had moved. In a univariate analysis, a change in the home environment (moving home, home adjustments or a move to a nursing home) correlated with functional independence (Barthel index, ρ = −0.69, p < 0.001) and the need for assistance (Chi 2 = 22.8, p < 0.001) but was independent of age.

| Residence | |

| Removal | 5 (7.4%) |

| Installations | 18 (26.5%) |

| changes in room function( n = 8), threshold ramps (3), bathroom (1), slope (1), grab rail (1) | |

| No help (patients returned over to the former residence) | 28 (45.9%) |

| At least a help (of which a patient in nursing home) | 33 |

| Instrumental device | 23 (37%) |

| Human help family | 29 (47%) of which joint: 19 |

| External | 28 (45.9%) |

| nurse (6), nursing auxiliary (1), carer (3), home help (3), meal delivery (3), family visitor (1), psychologist (5) | |

| Rehabilitation care | |

| Physiotherapy | 15 (24.6%) |

| Speech therapy | 9 (14.7%) |

| Orthoptics | 4 (6.6%) |

| Occupational therapy | 2 (3.3%) |

| Follow-up by PMR | 3 (4.9%) |

Twenty-eight patients (45.9%) did not need any help but 23 others (37%) required an instrumental device ( Table 5 ), 29 (47%) needed family help and 28 (45.9%) required external human help. In a univariate analysis, the need for assistance was correlated with the Barthel index ( ρ = −0.62, p < 0.001), the IADL score ( ρ = 0.43, p < 0.001) and depression (Chi 2 = 15.2, p < 0.001) but was independent of age and gender. Of the patients who received help, 23 nevertheless had a Barthel index score above 80 and 19 had a IADL score of 5 or less ( Table 6 ). Ten of these suffered from depression.

| Kitchen, dinning | Bathing, dressing | Toilet | Bed | Transfers | Mobility | Safety |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tables (3) | Grap rails (11) | Grap rails in toilet (7) | Electrical medical beds (5) | Easy chairs (2) | Wheel chair (7) | Telephone in each part (1) |

| Nelson knife (1) | Bath mat (2) | Commode (1) | Pressure relieving mattress (3) | Mobile hoists (1) | Walking frames (1) | |

| Modified utensils (2) | Bath board (3) | Raised toilet seat (1) | Adjustable crutches (1) | |||

| Shoe-horn (1) | Adjustable tripod stick (6) | |||||

| Walking sticks (8) | ||||||

| Ankle foot orthesis (2) | ||||||

| Orthopedic shoes (3) |

| Need for assistance n = 33 | No assistance n = 28 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technical | Human | Total | ||

| Barthel index | ||||

| <60 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 0 |

| 60–80 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| >80 | 13 | 18 | 23 | 28 |

| IADL | ||||

| ≤5 | 10 | 15 | 19 | 25 |

| >5 | 13 | 13 | 14 | 3 |

Twenty-six patients (i.e. 42% of the 61 included patients) were discharged to a PRM unit. This type of discharge was not related to age, gender, marital status, employment status or stroke type. The length of the stay in the acute ward was significantly longer for these patients (32.8 days, versus 14 days for the others [ p < 0.01]). The average length of stay in the PRM unit was 3 months and was independent of the patients’ age, stroke type, length of stay in the acute ward, marital status and the home setting (type and accessibility). Rehabilitated patients needed more help ( Table 7 ): of these 26 patients, 16 had to make home adjustment or move. They used more technical aids, relied on their family more and underwent more rehabilitation maintenance. However, these patients did not require more external (i.e. non-family) human help.

| Rehabilitation n = 26 | No rehabilitation n = 35 | |

|---|---|---|

| Barthel index | ||

| <80 | 6 | 4 |

| >80 | 20 | 31 a |

| IADL | ||

| ≤5 | 15 | 29 |

| >5 | 11 | 6 a |

| Moving house, modifications | 16 | 7 a |

| Depression | 14 | 11 |

| Walking outdoors | 26 | 33 |

| Reduction in leisure activities | 20 | 14 a |

| Technical aid | 13 | 7 a |

| Human help by family member | 15 out of 18 | 10 out of 35 a |

| Other human help | 17 | 11 |

| Number of rehabilitation sessions | 2.03 | 0.6 a |

| Stop driving a car | 18 | 13 a |

Of the 13 patients in employment at the time of the stroke, only seven patients returned to work. This parameter was understandably influenced by pre-stroke employment status and by age but was independent of gender, type of stroke, rehabilitation and level of independence. Thirty-seven patients (60.6%) had to reduce at least one type of leisure activity after their stroke. The reduction in leisure activity correlated with the Barthel index ( ρ = −0.61, p < 0.001), modification of the home setting ( ρ = −0.52, p < 0.01) and the ability to drive a car ( ρ = −0.43, p < 0.001).

Twenty-five patients (41%) were suffering from a depressive state, according to the DSM IV-R. Depression was significantly related to the time since the stroke ( p < 0.001), the length of stay in the acute ward ( p < 0.001) and the IADL score ( p < 0.001).

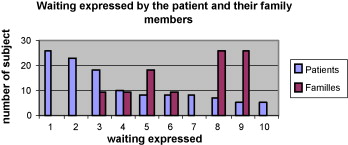

The patients’ main expectations and concerns were related to the recovery of independence, leisure activities and financial resources. Family members’ expectations and concerns were centred on a lack of information and the complexity of service delivery, discharge to home (considered as occurring too early and/or being inappropriate) and the delay in provision of help and resources ( Fig. 1 ). Approximately 10% of the patients and their families would have liked to have received more information on stroke.

1.3

Discussion

In the present study, we observed good functional recovery (as assessed by standard activity limitation scales) in 61 under-75 patients having suffered a first-ever stroke. Despite this good prognosis, these patients’ needs for assistance were major and should be taken into account in administrative management and resource planning for care networks.

The Barthel index is one of the most widely used activity limitation scales. In the present study, 87% of patients scored over 60, which suggests good functional recovery. As with most published studies in this field , we did not find any significant influence of age, gender or stroke type on the Barthel index. Granger et al. (in 1992) and San Segundo et al. (in 2007) did find some influence of age but their patients were older than ours. In contrast to the Limoges study , we found a significant correlation between the Barthel index score and the length of stay in an acute unit, although the studies again differed in terms of patient age. Given that the Barthel index is primarily designed to assess physical activity limitations, we also used addition Lawton’s IADL scale to take into account the role played by cognitive factors in independence. Indeed, a lower proportion (64%) of patients were fully independent according to this score (i.e. a score below 5). One in five patients suffered from severe cognitive disorders (i.e. a score above 10).

These relatively high rates of independence recovery contrasted with the high number of patients (23 to 29) who still used technical aids and/or required human help. This finding may be related to a lack of sensitivity for the scales we used; the FIM (which takes into account the amount of help needed to perform a task) would perhaps have yielded lower scores in patients requiring assistance.

One third of our patients suffered some physical activity limitations, i.e. reduced indoor mobility or walking. Unsurprisingly, these individuals coped with these limitations by moving home, adapting their home environment changes and/or using technical aids (such as wheelchairs, walking sticks and fittings in bathrooms and toilets). The cost to the community should not be underestimated. However, what should we think about the help required by patients who were free of severe physical or cognitive impairment? Did they really need help or did they feel they had to ask for help? No fewer than 42% of our patients fulfilled the DSM-NR criteria for a depressive state, which is somewhat higher than in the literature . In this study, the requirement for human help was significantly related to depression. There is a need for further studies on the possible value of antidepressant drugs and psychotherapy in stroke patients with a high requirement for help, despite recovery of a good degree of independence.

Human help may be provided by professionals or by family members. Unfortunately, our data did not allow for a fine-grain analysis of the role played by family members, relative to professional caregivers. Evans and Bishop observed that returning home after stroke was easier when a close relative (especially the spouse) was the main caregiver. This aspect had also a positive role on the close relative’s mood and ability to cope .

The patients’ expectations and concerns differed qualitatively from those of the family caregivers. Patients were more concerned with problems related to their own health status and the latter’s impact on their independence, leisure activities and financial resources, whereas family members were much more concerned with the type and amount of help they could receive. Indeed, providing the family caregiver with professional assistance from time to time would allow him/her more leisure activities and time for himself/herself and would improve his/her quality of life. However, our study does not provide further information on this question. The retrospective nature of our study prevented us from performing a detailed analysis of the role of rehabilitation on expectations, concerns and needs. We did not find any relationship between length of stay in the rehabilitation unit and the type and amount of help needed later on.

Some limitations and potential sources of bias should be kept in mind when considering our results. Patients admitted to the Bordeaux Neurovascular Unit were consecutively included, which avoided the usual severity bias in studies performed in rehabilitation units. However, we were unable to compare the mean age of patients lost to follow-up with that of patients who were assessed 17 months later. We decided not to include patients over 75 because in our city, they are treated in a different care network. Two patients under the age of 40 were also excluded because their living conditions and stroke type were very unusual and differed significantly from the other included patients. Nevertheless, age had little influence on independence in this study and was only related to outdoor activity. This agrees with the findings of previous studies but needs to be checked in a further study including older patients. Another concern is that two thirds of our patients (including all 10 with haemorrhagic stroke) were male. This might be a source bias, since the literature values for the proportion of male patients are generally lower . However, this observation might be related to the relatively lower age of the patients included in this study . Furthermore, this potential source of bias is unlikely to be of much importance because we (as others) did not find a significant influence of gender on independence, expectations or needs . Lastly, few of the patients in the present study lived alone; 75% lived with a spouse and 17% even had at least one dependent child. Hence, the need for an external (professional) caregiver or admission to a nursing home were perhaps lower than in studies including older subjects , and the extent of these needs were perhaps underestimated here.

In conclusion, patients who suffer their first-ever stroke before the age of 75 have a relatively good functional prognosis. However, more than one third feel depressed, have expectations and concerns with regard to their independence, resources and leisure activities and ask for human help. This dimension is underestimated by current activity limitation scales and should be better taken into account when managing service delivery and resource allocation in stroke care networks.

2

Version française

On estime qu’en France, chaque année, 120 000 personnes sont victimes d’un nouvel accident vasculaire cérébral (AVC). La mortalité de l’AVC à 12 mois est estimée entre 10 et 12 %, et représente la troisième cause de mortalité dans les pays industrialisés . Parmi les survivants, on estime que 50 % développeront des troubles dépressifs dans l’année, 25 % une démence (deuxième cause de démence) et l’AVC représente la première cause de limitations acquises d’activité chez l’adulte . Cette pathologie pose ainsi un problème majeur de santé publique de par son incidence, sa mortalité, le nombre important de patients dépendants qu’il occasionne, les séquelles psychologiques pour le patient mais aussi pour les proches. Cela entraînant bien sur un coût social non négligeable : élaboré à l’aide des comptes de la protection sociale, celui-ci a été évalué en 2002 à 27,5 milliards d’euros soit 1,81 % du produit intérieur brut .

Le devenir fonctionnel après un AVC est donc un sujet de préoccupation aussi bien pour les acteurs du soin neurologique aigu et de la réadaptation que pour les décideurs de la santé et des aides médico-sociales à mettre en œuvre. De très nombreuses études prédictives ont été consacrées à ce sujet, pour la plupart avec un recul inférieur ou limité à un an et menées avec des échelles de limitations d’activité qui ont fait leurs preuves dans ce domaine, l’index de Barthel et/ou la mesure d’indépendance fonctionnelle . Par exemple, Tilling et al. en 2001 ont étudié la récupération fonctionnelle à un an chez des patients de 70 ans en moyenne et a retenu les troubles urinaires, la dysarthrie, le sexe féminin, l’existence d’un handicap avant l’AVC comme éléments péjoratifs . San Segundo et al. ont retenu en 2007 un modèle prédictif de difficultés de retour à domicile à sept variables : isolement social, score inférieur à 50 à la mesure d’indépendance fonctionnelle, âge supérieur à 75 ans, hémiparésie gauche, barrières architecturales, antécédents cardiovasculaires et sexe masculin . L’un de nous a étudié en 2004 à Limoges les facteurs prédictifs du devenir fonctionnel et du retour à domicile d’une cohorte de 156 sujets après un premier AVC hémisphérique à un an . L’âge moyen des patients était de 72 ans et 29 % avaient plus de 80 ans. Dans cette étude, les facteurs prédictifs indépendants précoces d’un mauvais devenir fonctionnel étaient un index de Barthel faible à j2 et progressant peu entre j2 et j15, l’existence de troubles des fonctions exécutives et des antécédents de maladie neurologique invalidante. L’évolution de l’index de Barthel entre j2 et un an était moins bonne chez les patients âgés et présentant des troubles vésico-sphinctériens. Enfin, les facteurs initiaux les plus prédictifs du retour à domicile étaient la nature ischémique de l’AVC, un index de Barthel élevé à j15, l’absence d’incontinence urinaire à j15 et d’héminégligence, et le fait de vivre en couple.

Les informations fournies par ce type d’échelle de limitation d’activité sont-elles suffisantes pour planifier sur le terrain les aides nécessaires et les ressources à mettre en œuvre pour une filière de soin post-AVC ? Ou faut-il disposer aussi de données détaillées sur les conditions de vie de ces personnes, les aides techniques et humaines dont elles sont besoin, et quelles sont leurs attentes ? En outre, bien que l’essentiel de la récupération fonctionnelle survienne au cours des trois premiers mois, un recul supérieur à un an permet de connaître la filière de soins en totalité, après d’éventuels changements d’orientation, ainsi que les changements ou aménagements de domicile éventuels et les aides mises en place et l’adaptation physique et mentale du patient et de sa famille à ces nouvelles conditions de vie. L’objectif de la présente étude est d’évaluer chez des patients victimes d’AVC constitué l’autonomie, les aménagements du domicile, les soins de rééducation, les aides techniques et les aides humaines favorisant un retour à domicile dans les meilleures conditions possibles un à deux ans après l’attaque. Nous avons limité notre étude aux patients âgés de moins de 75 ans, car dans notre ville les patients d’âge supérieur font l’objet d’une filière différente, spécifique, de réadaptation gériatrique, organisée par l’un de nous .

2.1

Matériel et méthode

Il s’agit d’une enquête unicentrique, rétrospective sans groupe témoin, menée par hétéro-questionnaires remplis au domicile, ou au cours d’un entretien téléphonique auprès de patients victimes d’un premier accident vasculaire cérébral.

2.1.1

Population

Les dossiers de tous les patients hospitalisés pour AVC constitué entre octobre 2003 et avril 2004 dans le service de neurologie du CHU de Bordeaux dirigé par l’un des auteurs et spécialisé dans l’AVC ont été consultés.

2.1.2

Critères d’inclusion

Un AVC constitué a été défini selon l’OMS par un déficit neurologique focal et d’installation brutale d’une durée supérieure à 24 heures secondaire à une ischémie ou à une hémorragie intracrânienne. Ont été inclus les sujets âgés de 40 à 75 ans victimes d’un premier AVC ischémique ou hémorragique, de localisation hémisphérique ou cérébelleuse, confirmé par une imagerie cérébrale (scanner ou IRM).

2.1.3

Critères d’exclusion

Ont été exclus les patients décédés avant leur admission en service de neurologie, les accidents ischémiques transitoires, les hémorragies méningées, les récidives d’AVC, les patients résidant en dehors du département de la Gironde et les patients ayant complètement récupéré à la sortie du service de neurologie.

2.1.4

Procédure d’évaluation

Le médecin enquêteur avait un rôle d’observateur indépendant et n’a pas participé à la prise en charge des patients, ni à leur suivi médical qui s’est fait selon le fonctionnement habituel des services. Le recueil des données a été effectué entre octobre 2004 et juillet 2005, donc 12 à 24 mois après l’AVC, avec une moyenne de 17,3 mois. Après information du médecin traitant, un courrier présentant les buts de l’enquête et un formulaire de consentement ont été adressés aux patients. Les informations concernant l’AVC, la biographie des patients, leurs coordonnées et celles de leurs médecins traitants ont été recherchées dans le dossier médical. Toutes les autres informations ont été obtenues par hétéro-questionnaire du patient et de sa famille, renseigné au domicile pour les patients dont les médecins traitants ne rapportaient qu’une récupération partielle, et par téléphone pour les patients dont les médecins rapportaient une récupération et une autonomie totale.

2.1.5

Données recueillies

Les limitations d’activités de vie quotidienne ont été évaluées par l’index de Barthel et l’incapacité fonctionnelle pour les actes élaborés de la vie quotidienne par l’échelle d’activités instrumentales de la vie courante IADL de Lawton . Le diagnostic de dépression a été établi selon les critères du diagnosis and statistical manual (DSM IV-R) . Les soins de rééducation résiduels, les aides techniques, humaines et les éventuels aménagements de domicile ont été recensés. Enfin, les patients ont précisé l’augmentation, la diminution ou la conservation à la même fréquence de leurs loisirs pratiqués à l’extérieur, à domicile et de leurs loisirs sociaux (loisirs pratiqués avec d’autres personnes que leur famille).

Sur le plan statistique, les moyennes des variables dépendantes quantitatives ont été comparées avec le test de Mann et Whitney. Les variables qualitatives ont été comparées avec le test Khi 2 . Les résultats ont été considérés comme significatifs si p < 0,05. L’influence des variables indépendantes a été recherchée par le test de Kruskal-Wallis (KW) et le coefficient de corrélation de Spearman.

2.2

Résultats

En tenant compte des critères d’exclusion, 94 patients atteints d’un premier AVC constitué entre octobre 2003 et avril 2004, non décédés et présentant encore un déficit à la sortie du service de neurologie ont été répertoriés. Après décompte dans ce groupe de cinq patients décédés avant le recueil des données, de 22 patients perdus de vue pour raison géographique, de deux patients ayant refusé de participer à l’étude après explication des buts de celle-ci et de quatre patients dont les médecins traitants ont refusé de participer à l’étude, 61 patients ont finalement pu être inclus. Trente-et-un ont été vus à domicile avec ou sans leurs proches et 30 ont été contactés par téléphone.

Les principales caractéristiques de ces patients sont résumées dans les Tableaux 1 et 2 . L’âge moyen était de 64 ± 8,5 ans au moment de l’étude, avec une distribution non gaussienne. Comme attendu, les AVC ischémiques prédominaient largement. À la sortie du service de neurologie, 23 patients (34 %) présentaient encore une hémiplégie et/ou une aphasie et 26 (42 %) ont bénéficié d’un séjour en service ou centre de médecine physique et réadaptation (MPR).