Sternoclavicular Joint: Primary and Revision Reconstruction

Michael A. Wirth

Charles A. Rockwood

M. A. Wirth: Department of Orthopaedics, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, Texas.

C. A. Rockwood: Department of Orthopaedics, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, Texas.

PATHOLOGY AND EVALUATION

Biomechanics and Mechanisms of Injury

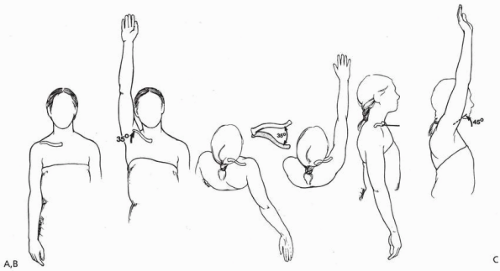

The sternoclavicular (SC) joint is freely moveable and functions almost like a ball-and-socket joint with motion in almost all planes, including rotation.2,11 The clavicle, and therefore the SC joint, in normal shoulder motion is capable of 30 to 35 degrees of upward elevation, 35 degrees of combined forward and backward movement, and 45 to 50 degrees of rotation around its long axis (Fig. 21-1). It is most likely the most frequently moved joint of the long bones in the body, because almost any motion of the upper extremity is transferred proximally to the SC joint.

Either direct or indirect force can produce a dislocation of the SC joint. Because the SC joint is subject to practically every motion of the upper extremity and because the joint is small and incongruous, one would think that it would be the most commonly dislocated joint in the body. However, the ligamentous supporting structure is strong and so well designed that it is, in fact, one of the least commonly dislocated joints in the body. A traumatic dislocation of the SC joint usually occurs only after a tremendous force, either direct or indirect, has been applied to the shoulder.

Direct Force

When a force is applied directly to the anteromedial aspect of the clavicle, the clavicle is pushed posteriorly behind the sternum and into the mediastinum. This can occur in a variety of ways: an athlete lying on his or her back on the ground is struck by the knee of a jumper landing directly on the medial end of the clavicle; a kick is delivered to the front of the medial clavicle; a person lying supine is run over by a vehicle; or a person is pinned between a vehicle and a wall (Fig. 21-2). Anatomically, it is essentially impossible for a direct force to produce an anterior SC dislocation.

Indirect Force

A force can be applied indirectly to the SC joint from the anterolateral or posterolateral aspects of the shoulder. This is the most common mechanism of injury to the SC joint. Mehta and coworkers14 reported that three of four posterior SC dislocations were produced by indirect force, and Heinig8 reported that indirect force was responsible for eight of nine cases of posterior SC dislocations. Indirect force was the most common mechanism of injury in the authors’ 185 patients. If the shoulder is compressed and rolled forward, an ipsilateral posterior dislocation results; if the shoulder is compressed and rolled backward, an ipsilateral

anterior dislocation results. One of the most common causes that the authors have seen is a pile-on in a football game. In this instance, a player falls on the ground, landing on the lateral shoulder; before he can get out of the way, several players pile on top of his opposite shoulder, which applies significant compressive force on the clavicle down toward the sternum. If, during the compression, the shoulder is rolled forward, the force directed down the clavicle produces a posterior dislocation of the SC joint. If the shoulder is compressed and rolled backward, the force directed down the clavicle produces an anterior dislocation of the SC joint. Other types of indirect forces that can produce SC dislocation are a cave-in on a ditch digger, with lateral compression of the shoulders by the falling dirt; lateral compressive forces on the shoulder when a person is pinned between a vehicle and a wall; and a fall on the outstretched abducted arm, which drives the shoulder medially in the same manner as a lateral compression on the shoulder.

anterior dislocation results. One of the most common causes that the authors have seen is a pile-on in a football game. In this instance, a player falls on the ground, landing on the lateral shoulder; before he can get out of the way, several players pile on top of his opposite shoulder, which applies significant compressive force on the clavicle down toward the sternum. If, during the compression, the shoulder is rolled forward, the force directed down the clavicle produces a posterior dislocation of the SC joint. If the shoulder is compressed and rolled backward, the force directed down the clavicle produces an anterior dislocation of the SC joint. Other types of indirect forces that can produce SC dislocation are a cave-in on a ditch digger, with lateral compression of the shoulders by the falling dirt; lateral compressive forces on the shoulder when a person is pinned between a vehicle and a wall; and a fall on the outstretched abducted arm, which drives the shoulder medially in the same manner as a lateral compression on the shoulder.

History and Physical Examination

It is very important to take a careful history and perform a thorough physical examination. The physician should obtain x-rays, tomograms, computed tomography (CT) scans, or angio-CT scans to document whether there is any compression of the great vessels in the neck or arm and to determine whether there is a structural cause for difficulty in swallowing or breathing. It is also important to determine whether the patient has any feeling of choking or hoarseness. If any of these symptoms are present, indicating pressure on the mediastinum, the appropriate cardiovascular or thoracic specialist should be consulted.

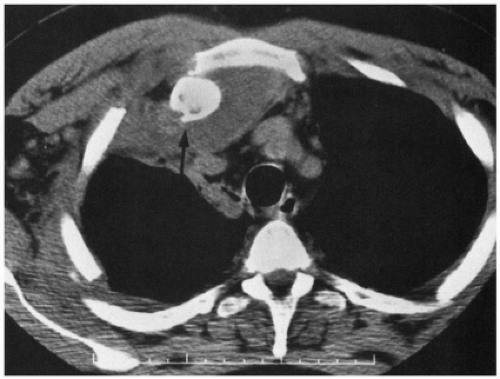

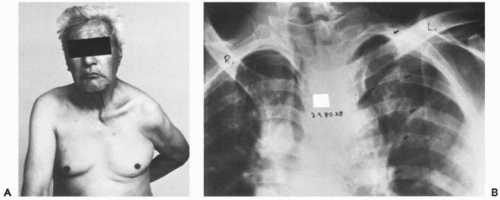

Although the diagnosis of anterior or posterior injury of the SC joint used to be made based on a physical examination, it is now known that anterior swelling and firmness are not diagnostic of an anterior injury. The authors have been fooled on several occasions when the patient appeared to have an anterior dislocation on physical examination, but x-rays documented a posterior problem (Fig. 21-3). Therefore, the authors recommend that the clinical impression always be documented with appropriate x-rays before making any decision to treat or not to treat.

Radiographs

The older literature reflects that routine x-rays of the SC joint, regardless of the special views, are difficult to interpret. Special oblique views of the chest have been recommended, but because of the distortion of one of the clavicles over the other, interpretation is difficult.

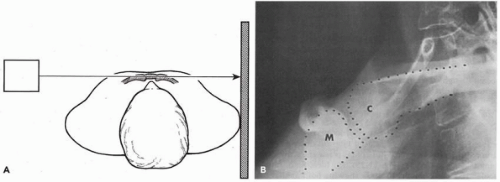

Heinig View

With the patient in a supine position, the x-ray tube is placed approximately 30 inches from the involved SC joint, and the central ray is directed tangential to the joint and parallel to the opposite clavicle. The cassette is placed against the opposite shoulder and centered on the manubrium (Fig. 21-4).

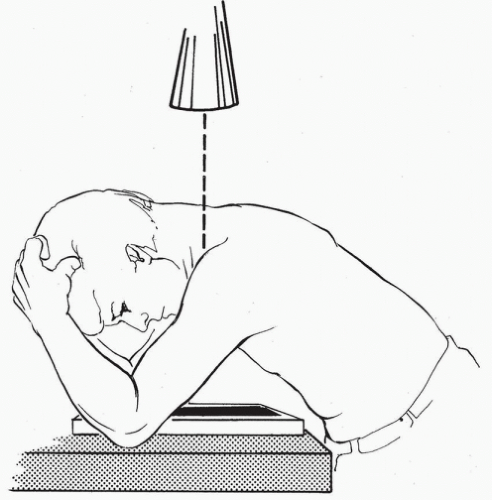

Hobbs View

In the Hobbs view, the patient is seated at the x-ray table, high enough to lean forward over the table. The cassette is on the table, and the lower anterior rib cage is against the cassette (Fig. 21-5). The patient leans forward so that the

nape of his or her flexed neck is almost parallel to the table. The flexed elbows straddle the cassette and support the head and neck. The x-ray source is above the nape of the neck, and the beam passes through the cervical spine to project the SC joints onto the cassette.

nape of his or her flexed neck is almost parallel to the table. The flexed elbows straddle the cassette and support the head and neck. The x-ray source is above the nape of the neck, and the beam passes through the cervical spine to project the SC joints onto the cassette.

Serendipity View

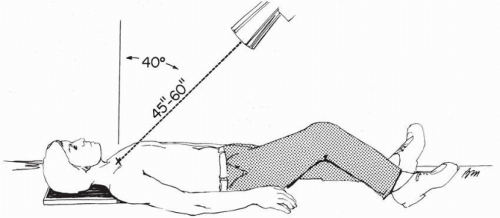

The “serendipity view” is aptly named because that is the way it was developed. The senior author accidentally noted the next best thing to having a true cephalocaudal lateral view of the SC joint is a 40-degree cephalic tilt view. The patient is positioned on his or her back squarely and in the center of the x-ray table. The tube is tilted at a 40-degree angle off the vertical and centered directly on the sternum (Fig. 21-6).

Computed Tomography, Magnetic Resonance Imaging, and Other Studies

Computed Tomography Scans

Without question, the CT scan is the best technique to study any or all problems of the SC joint. It clearly distinguishes injuries of the joint from fractures of the medial clavicle and defines minor subluxations of the joint. The orthopedist must ask for CT scans of both SC joints and the medial one-half of both clavicles so that the injured side can be compared with the uninjured side.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging Scans

When there are questions of diagnosis between dislocations of the SC joint or physeal injury in children and young adults, the MRI scan can be used to determine whether the epiphysis has been displaced with the clavicle or is still adjacent to the manubrium.

Concomitant Injuries

Injuries that occur in association with trauma to the SC joint are primarily posterior dislocations. These injuries have been associated with significant morbidity and include the following: pneumothorax and laceration of the superior vena cava21; respiratory distress, venous congestion in the neck, rupture of the esophagus with abscess and osteomyelitis of the clavicle3; pressure on the subclavian artery in an untreated patient12; occlusion of the subclavian artery late in a patient who was not treated8; compression of the right common carotid artery by a fracture-dislocation of the SC joint12; brachial plexus compression17; hoarseness of the voice, onset of snoring, and voice changes from falsetto with movement of the arm and a fatal tracheoesophageal fistulae.27

STERNOCLAVICULAR INSTABILITY: ANTERIOR

Acute Versus Chronic Subluxation

Patients who develop anterior SC instability may present acutely or several months after the development of this condition. In addition, anterior instability can develop in the absence of trauma. In a review by Rockwood and Odor22 of 37 patients with spontaneous atraumatic subluxation, 29 were managed without surgery and 8 were treated with a surgical reconstruction elsewhere. With an average follow-up of more than 8 years, all 29 patients who did not undergo operation were doing well without limitations of activity or lifestyle. The 8 patients treated with surgery had increased pain, limitation of activity, alteration of lifestyle, persistent instability, and a significant scar. In many instances, the patient, before a previous reconstruction or resection, had minimal discomfort, had an excellent range of motion, and only complained of the “bump” that slipped in and out of place with certain motions. Postoperatively, the patient still had the bump, along with a scar and painful range of motion.

Nonoperative Management

For an acute subluxation of the SC joint, application of ice is recommended for the first 12 hours, followed by heat for the next 24 to 48 hours. The joint may be reduced by drawing the shoulders backward as if reducing and holding a fracture of the clavicle. A clavicle strap can be used to hold the reduction. A sling and swath should also be used to hold up the shoulder and prevent motion of the arm. The patient should be protected from further possible injury for 4 to 6 weeks. Plaster figure-of-eight dressing, a simple sling to support the arm, a soft figure-of-eight bandage with a sling, and, occasionally, adhesive strapping over the medial end of the clavicle have all been recommended.

Is There Ever a Role for Operative Treatment?

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree