Sternoclavicular Fracture Injury

R. Jay Lee

Afamefuna M. Nduaguba

David A. Spiegel

DEFINITION

Sternoclavicular fracture-dislocation is an injury to the only bony articulation between the upper extremity and the axial skeleton.

Sternoclavicular fracture-dislocation is reported to be only 3% of upper extremity dislocations, 1% of all joint dislocations.5

Anterior fracture-dislocations are more common, but posterior fracture-dislocations can be associated with life-threatening complications and should be diagnosed promptly.

The majority of the existing literature concerns the adult population, and there are a limited number of studies, mostly case reports, concerning the management in children and adolescents.

ANATOMY

Sternoclavicular joint

The clavicle is the first bone to ossify at intrauterine week 5. However, the medial epiphysis does not ossify until 18 to 20 years of age and does not fuse until 22 to 25 years of age.22

The sternoclavicular joint is formed by the sternal end of the clavicle, the clavicular notch of the manubrium, and the cartilage of the first rib. Only a small portion of the medial end of the clavicle is covered by articular cartilage, anteriorly and inferiorly, and the majority of the articulation between the medial clavicle and the manubrium is fibrous.19

The primary stabilizers to anterior and posterior translation are the posterior and anterior capsule. The posterior capsule provides the most restraint to both anterior and posterior translation, whereas the anterior capsule provides additional restraint to anterior translation.18 There is minimal, if any, bony constraint to motion at this articulation.18

The costoclavicular and interclavicular ligaments do little to limit anterior and posterior translation.18

Mediastinal structures

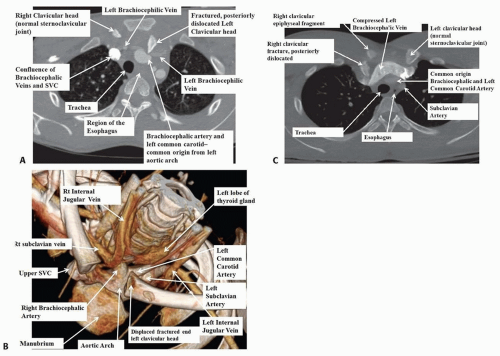

Important mediastinal structures lie in close proximity to the sternoclavicular joint: the trachea, lungs, esophagus, brachiocephalic vein, subclavian artery, and brachial plexus (FIG 1).

PATHOGENESIS

Sternoclavicular fracture-dislocations can result from direct or indirect force.

A direct anteromedial force usually results in the clavicle being pushed posteriorly into the sternum and into the mediastinum.

An indirect lateral force transmitted along the axis of the clavicle can cause either an anterior or posterior fracture-dislocation, depending on the position of the shoulder relative to the manubrium.12

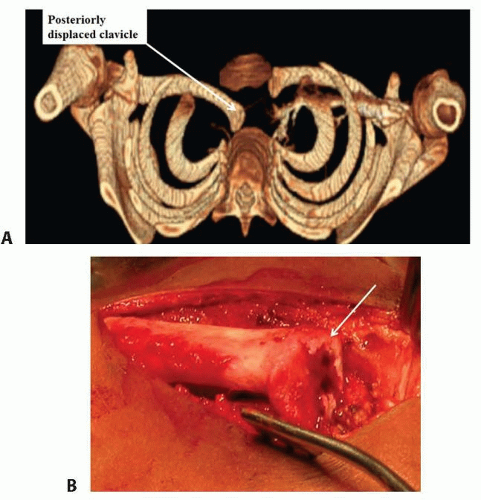

These injuries are often physeal fractures in children rather than pure dislocations. However, these are difficult to distinguish on imaging studies, as the medial epiphysis does not ossify until age 18 to 20 years (FIG 2).

NATURAL HISTORY

Posteriorly displaced fractures or dislocations can result in life-threatening and other complications:

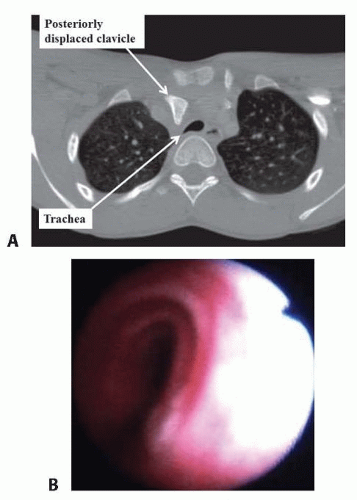

Obstruction of the trachea can result in acute airway compromise (FIG 3), and obstruction of the esophagus can result in dysphagia. If untreated, tracheoesophageal fistulas can result.20

Obstruction of the underlying brachiocephalic vein or subclavian artery can result in compromised perfusion. If untreated, erosion of the vessels can result.6

Impingement of underlying structures can lead to brachial plexopathy17 and thoracic outlet syndrome.7

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

A careful history and physical examination is crucial for identifying this injury. The patient should describe the mechanism of injury and should be asked to point to where the area of maximal discomfort is.

FIG 3 • A,B. The preoperative CT of the same patient as in FIG 2 shows tracheal compression, which in the endoscopic view is reflected in a narrowed trachea.

As with all traumas in the acute setting, airway, breathing, and circulation (ABCs) should be assessed first, as posterior sternoclavicular fracture-dislocation can compromise any of them.

A careful history may elicit symptoms consistent with obstruction such as dyspnea or dysphagia.

Physical examination should include the neck, thorax, and shoulder girdles, with particular attention to the neurovascular examination.

In contrast to anterior fracture-dislocations, where pain and sternoclavicular prominence coincide, posterior fracture-dislocations present with pain contralateral to the “prominent” appearing joint.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Sternoclavicular injuries may be missed on standard radiographs. Serendipity views, where the beam centered on the manubrium is aimed 40-degree cephalad, may aid in the diagnosis.

Computed tomography (CT) is perhaps the best imaging modality to evaluate the sternoclavicular articulation. Strong consideration should be given to obtain the study with intravenous contrast when such injuries are suspected.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can also demonstrate the pathology well, can provide greater soft tissue detail, and also differentiate between a fracture and a true dislocation. However, obtaining an MRI may not be practical or achievable in the acute setting. We do not routinely obtain MRI’s in our practice.

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Nonoperative treatment may be warranted if fracture displacement or joint subluxation is minimal, and there is no compression of any neurovascular structures.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Reduction is suggested for those posterior sternoclavicular fractures which are displaced and also those with a true dislocation.

Options for reduction include closed and open techniques. Indications for open reduction include fractures or dislocations unable to be reduced by closed means or the inability to maintain a reduction.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree