The careful and well-planned sideline assessment of concussion can be the difference between a good and bad outcome when managing sport-related concussion. In most cases, the sideline assessment serves as a triage for determining if an injury, such as a concussion, has actually occurred, and if so, establishes a benchmark for determining whether a more serious and potentially catastrophic condition could be developing. Concussions can evolve into something more serious if signs and symptoms go undetected or are ignored. Although these are very rare events, they must always be at the forefront of the clinician’s mind.

The careful and well-planned sideline assessment of concussion can be the difference between a good and bad outcome when managing sport-related concussion. In most cases, the sideline assessment serves as a triage for determining if an injury, such as a concussion, has actually occurred, and if so, establishes a benchmark for determining whether a more serious and potentially catastrophic condition could be developing. Given its description as “a complex pathophysiological process affecting the brain, induced by traumatic biomechanical forces,” concussions can evolve into something more serious if signs and symptoms go undetected or are ignored. Although these are very rare events, they must always be at the forefront of the clinician’s mind.

Concussions occur in all sports, and though the incidence varies widely between sports, in some sports (eg, women’s ice hockey) the incidence of concussion may exceed that of all other injuries. Regardless of the setting, sports medicine clinicians must be prepared to manage these complex and somewhat misunderstood injuries, which have been labeled by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as a “hidden epidemic.” Developing and instituting a concussion policy and management protocol constitutes the first step in properly treating the athlete suspected of sustaining a concussion, which should be backed by proper planning and practice of the on-field management strategy.

Much of the inherent complexity in evaluating athletes suspected of sustaining a concussion lies in the broad spectrum of outcomes associated with the injury. Knowing the athlete and his or her background, concussion history, and ability and willingness to provide information about his or her condition can minimize the challenges of evaluating the injury. Research has shown that impact location and magnitude, previous history of concussive injuries, learning disabilities, and age can alter the risk of concussion and in some cases the outcomes following injury. To further complicate matters, no definitive diagnostic tool is available for concussion at this time. Standard computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are insensitive to the functional deficits observed following concussion. Functional MRI, diffuse tensor imaging, single-photon emission computed tomography, and magnetic resonance spectroscopy are showing promise, but their widespread use as an objective diagnostic tool has not yet been substantiated. Several objective clinical measures (neuropsychological and balance tests) are recommended to support the clinical examination. Although these tools have vastly improved the concussion diagnosis in recent years, the clinical examination remains the gold standard for evaluation.

Emergency action planning and establishing a concussion policy

Before the first preseason practice, the sports medicine clinician in charge of on-field injury management should make sure to have an emergency action plan in place. This plan should incorporate strategies to address heat illness, cardiac sudden death, weather and, of course, a specific plan for managing concussion and cervical spine injury ( Box 1 ). When developing the concussion component of the plan, the clinician should develop a concussion policy and concussion protocol. The protocol is different from the policy, in that it specifically outlines the clinical tests that will be used for assessments and a graduated return-to-play progression. The policy itself outlines the steps to be put in place preseason, including roles and responsibilities of the team. The policy should at the very least consider 4 components: (1) preseason planning, (2) on-field/sideline evaluation, (3) removal from play, and (4) graduated return-to-play progression. Concussion education materials and sample concussion policies are available at http://www.ncaa.org/health-safety . Although the focus of this article is on the sideline examination and removal from play, the planning component is very important. It is during the preseason planning and practice that the roles and responsibilities in the event of a concussion should be clarified. For example, the concussion protocol should ensure clarity and an understanding regarding:

- •

Who will be responsible for the on-field response?

- •

Who will conduct the emergency assessment and handle communication if advanced help is needed?

- •

Who will observe the athlete on the sideline following injury?

- •

Who will make a concussion diagnosis or return-to-play decision, especially in the absence of a physician?

- •

Who will communicate the diagnosis and prognosis with the parents and coaches?

- 1.

Establish roles: adapt to specific team/sport/venue; it may be best to have more than one person assigned to each role in case of absence/turnover

- a.

Immediate care of the athlete

- i.

Typically physician, Certified Athletic Trainer, first responder, but also those trained in basic life support

- i.

- b.

Activation of emergency medical system

- i.

Could be school administrator, anyone

- i.

- c.

Emergency equipment retrieval

- i.

Could be student assistant, coach, anyone

- i.

- d.

Direction of emergency medical responders to scene

- i.

Could be administrator, coach, student assistant, anyone

- i.

- a.

- 2.

Communication

- a.

Primary method

- i.

May be fixed (landline) or mobile (cellular phone, radio)

- ii.

List all key personnel and all phones associated with this person

- i.

- b.

Backup method

- i.

Often a landline

- i.

- c.

Test before event

- i.

Cell phone/radio reception can vary, batteries charged, landline working

- ii.

Make sure communication methods are accessible (identify and post location, are there locks or other barriers, change available for pay-phone)

- i.

- d.

Activation of emergency medical system

- i.

Identify contact numbers (911, ambulance, police, fire, hospital, poison control, suicide hotline)

- ii.

Prepare script (caller name/location/phone number, nature of emergency, number of victims and their condition, what treatment initiated, specific directions to scene)

- iii.

Post both of the above near communication devices, other visible locations in venue, and circulate to appropriate personnel

- i.

- e.

Student emergency information

- i.

Critical medical information (conditions, medications, allergies)

- ii.

Emergency contact information (parent/guardian)

- iii.

Accessible (keep with athletic trainer for example)

- i.

- a.

- 3.

Emergency equipment

- a.

Automated external defibrillators, bag-valve mask, spine board, splints

- b.

Personnel trained in advance on proper use

- c.

Must be accessible (identify and post location, within acceptable distance for each venue, are there locks or other barriers)

- d.

Proper condition and maintenance

- i.

document inspection (log book)

- i.

- a.

- 4.

Emergency transportation

- a.

Ambulance on site for high-risk events (know difference between basic life support and advanced life support vehicles/personnel)

- i.

Designated location

- ii.

Clear route for exiting venue

- i.

- b.

When ambulance not on site

- i.

Entrance to venue clearly marked and accessible

- ii.

Identify parking/loading point and confirm area is clear

- i.

- c.

Coordinate ahead of time with local emergency medical services

- a.

- 5.

Additional considerations

- a.

Must be venue specific (football field, gymnasium, and so forth)

- b.

Put plan in writing

- c.

Involve all appropriate personnel (administrators, coaches, sports medicine, emergency medical system)

- i.

Development

- ii.

Approval with signatures

- i.

- d.

Post the plan in visible areas of each venue and distribute

- e.

Review plan at least annually

- f.

Rehearse plan at least annually

- g.

Document

- i.

Events of emergency situation

- ii.

Evaluation of response

- iii.

Rehearsal, training, equipment maintenance

- i.

- a.

Specific considerations for Head and Neck Injury:

- 1.

Athletic trainer/first responder should be prepared to remove the face-mask from a football helmet to access a victim’s airway without moving the cervical spine

- 2.

Sports medicine team should communicate ahead of time with local emergency medical system

- a.

Agree on cervical spine immobilization techniques (eg, leave helmet and shoulder pads on for football players)

- b.

Type of immobilization equipment available on site and from emergency medical system

- a.

- 3.

Athletes and coaches should be trained not to move victim

In addition, preseason planning should include drills and planning for sporting events both at the home venue and outside of the local area. In both of these situations, it is important to assess the availability of emergency medical responders and the location of trauma centers, when available.

Depending on the setting (youth, high school, college, or professional), the sports medicine team should develop a plan for educating all personnel about concussion to include athletes, parents, coaches, and league and school officials. The education program should make it clear that it is the responsibility of the athletes, parents, and coaches to report any symptoms of concussion to the medical staff. The program should also discuss the potential long-term consequences of concussion, and expectations for safe play.

Ideally the concussion policy and protocol will include a preseason baseline evaluation, including a clinical examination that evaluates concussion-related symptoms, and the athlete’s orientation, memory, concentration, and balance. In addition, baseline neuropsychological testing has been shown to be a helpful adjunct and can be readministered post injury to identify the effects of the injury. The most commonly used neuropsychological tests assess a range of brain behaviors including memory, concentration, information processing, executive function, and reaction time. In some instances additional health care professionals may be needed to administer and interpret these tests.

Know your athletes and ensure they understand concussion

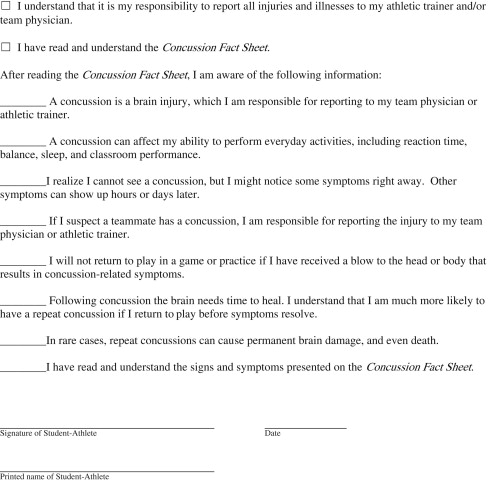

In many settings, athletic trainers represent the front line of defense in protecting concussed athletes from returning to a game or practice and placing themselves at risk for further injury. Athletic trainers have the advantage of knowing the personalities and habits of their athletes, which affords them the opportunity to rapidly identify alterations that would lead one to suspect a concussion has occurred. Once an athlete is suspected of sustaining a concussion, a physician should be involved in the return-to-play decision. Because the athletic trainer is often the lone health care provider, establishing an agreed-upon concussion policy and protocol beforehand is very important for appropriate management. Regardless of the setting, the athletes, coaches, and medical personnel must be educated about concussion and should read and sign a statement confirming that they understand the signs and symptoms of a concussion, and understand their responsibility to report a suspected concussion to the team’s medical staff ( Table 1 ).

Know your athletes and ensure they understand concussion

In many settings, athletic trainers represent the front line of defense in protecting concussed athletes from returning to a game or practice and placing themselves at risk for further injury. Athletic trainers have the advantage of knowing the personalities and habits of their athletes, which affords them the opportunity to rapidly identify alterations that would lead one to suspect a concussion has occurred. Once an athlete is suspected of sustaining a concussion, a physician should be involved in the return-to-play decision. Because the athletic trainer is often the lone health care provider, establishing an agreed-upon concussion policy and protocol beforehand is very important for appropriate management. Regardless of the setting, the athletes, coaches, and medical personnel must be educated about concussion and should read and sign a statement confirming that they understand the signs and symptoms of a concussion, and understand their responsibility to report a suspected concussion to the team’s medical staff ( Table 1 ).