LOW BACK & NECK PAIN

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Neck and back pain are the most common physical conditions for which patients seek medical attention.

History and physical examination are paramount in diagnosis, as imaging is often falsely positive or negative.

Finding the root cause of the symptoms is essential.

The chief complaint of spinal pain dominates in primary care offices and emergency departments across the United States. Once thought of as nuisance conditions associated with a speedy recovery, back and neck pain are now known to produce lingering problems for many patents, with few returning to preinjury activity. Despite increasing awareness of this problem, the incidence of spinal pain remains at about 80%, with 60% of adults reporting neck or low back pain within the previous 3 months.

Pain is merely a symptom; therefore, clinicians must evaluate for anatomic and physiologic causes of the pain, many of which are discussed elsewhere in this chapter. Assessing for so-called “red flags” is essential (Table 31–1). These well-known and established indicators may require careful assessment, changes in treatment plan, or emergency care or referral to another health care specialist. Ignoring these “red flag” indicators increases the likelihood of patient harm. “Yellow flags” are psychosocial factors that have been shown to be indicative of long-term disability and can become a barrier to treatment (Table 31–2).

|

|

|

|

|

Negative attitude (ie, that back pain is harmful or potentially severely disabling) Fear or avoidance behavior and reduction in activity levels Expectation that passive, rather than active, treatment will be beneficial Tendency to depression, low morale, and social withdrawal Social or financial problems |

The treatment of back and neck pain is dependent on etiology. The physiatrist must have a thorough knowledge of spinal disease in order to provide the best treatment for these patients. Although most acute exacerbations can be treated conservatively, a steady and steep rise in spinal procedures and surgeries has occurred.

The overall prognosis for spinal pain is poor. The pain may subside initially; however, the annual rate of recurrence is about 40%. Loss of function plays a large role in the poor prognosis. Up to 26% of patients with spinal pain report limitations in the amount or type work they can perform because of back pain. About 5% of the population state they cannot work at all because of health limitations resulting from back pain. Limitations seem to be most severe in senior citizens, leading to involuntary or early retirement. Work-related injuries present a particular challenge. Factors such as work restrictions, job satisfaction, and the presence of litigation affect the patient’s ability to return to work, and less than 1% of patients who are out of work for more than 1 year ever return.

SPONDYLOLISTHESIS & SPONDYLOLYSIS

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Spondylolysis is a defect in the pars interarticularis.

Spondylolisthesis involves the translation of one vertebra over another.

They often occur together, commonly at the lumbosacral junction, producing sensory, motor, and reflex changes.

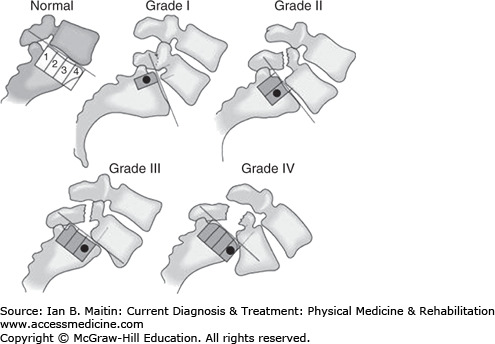

Spondylolysis is a defect in the pars interarticularis that is associated with spondylolisthesis in approximately 50% of cases. Spondylolisthesis is the slippage of one vertebral body with respect to the one beneath it. This most commonly occurs at the lumbosacral junction but can occur anywhere in the spine. Spondylolisthesis is classified based on etiology into six types (Table 31–3) and can be further graded based on the amount of vertebral subluxation in the sagittal plane (Figure 31–1).

| Class | Type | History |

|---|---|---|

| I | Dysplastic | Results from a congenital defect in the neural arch of L5 or S1. Symptoms first present in childhood, usually with radicular pain that worsens with extension and activity. Commonly seen at L5–S1. |

IIa IIb | Isthmic–spondylolysis Isthmic–pars elongation | Results from a defect in the pars interarticularis either through repeated stress (IIa) or congenitally (IIb). Presents in childhood or young adulthood with axial or radicular pain, or both, often with a history of repeated flexion–extension–rotational stress (eg, gymnastics). Commonly seen at L5–S1. |

| III | Degenerative | Manifests later in life with a chronic and progressive pattern of axial pain and neurogenic claudication. Commonly seen at L4–5. |

| IV | Traumatic | Occurs with acute axial and or limb pain following trauma. |

| V | Pathologic | Insidious onset caused by generalized bone disease (cancer, infection, metabolic disorder) that leads to attenuation of the posterior elements. |

| VI | Postsurgical | Onset may be gradual or acute. Caused by prior surgical resection of the lamina or facet without fusion. |

Table 31–3 summarizes key aspects of the disease process for various types of spondylolisthesis. Depending on the cause, onset of symptoms may be chronic or acute. Adequate workup must be completed to determine the pathologic causes of spondylolisthesis prior to initiating treatment with conservative methods.

In cases of severe slippage, neurologic compromise often produces motor, sensory, and reflex changes. Extension often exacerbates pain. Hyperlordosis of the lumbar spine along with hyperkyphosis of the thoracic spine may occur in compensation as the center of gravity shifts. A palpable step-off of the spinous process may be felt as one vertebra slides past another. Paraspinal muscle hypertonicity, restricted range of motion, and root tension signs may be common.

Standing radiographs are used to evaluate and grade lumbar spondylolisthesis. Lateral and oblique radiographs may show a fracture of the pars interarticularis, a classic fractured collar of the “Scotty dog.” On flexion and extension views, sagittal translation of greater than 4.5 mm in the lumbar spine and 2 mm in the cervical spine indicates instability, while sagittal rotation of greater than 11 degrees on the cervical spine and 15 degrees in the lumbar spine indicates instability. Thin-slice computed tomography (CT) scan without contrast can be helpful to visualize the bony anatomy and isthmic defects, as well as the spinal canal. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be helpful in viewing the neural structures, and bone scan may be helpful in demonstrating acute fractures. Younger patients have a higher risk for progression of isthmic or congenital spondylolisthesis. Serial radiographic studies (standing lateral films, only) should be performed every 6 months to follow these patients. Progression rarely occurs after adolescence.

Once the diagnosis of spondylolysis or spondylolisthesis is made, emphasis should be placed on finding the underlying cause, especially if pathologic fracture is suspected.

Most patients can be treated conservatively. If an isthmic lesion is acute, the patient should be restricted from provocative activities or sports until he or she is asymptomatic. Medications such as acetaminophen and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are often used to control the symptoms of pain associated with spondylolisthesis.

Physical therapy is an integral part of the patient’s rehabilitation process. The most accepted protocol includes activity and exercise that reduces extension stress. The goals of exercise are to improve abdominal strength and increase flexibility. Since tight hamstrings are almost always part of the clinical picture, appropriate hamstring stretching is important. Instruction in pelvic tilt exercises may help reduce any postural component causing increased lumbar lordosis.

Bracing for acute spondylolisthesis is controversial, but it has been shown to reduce symptoms and to facilitate healing. A thoracolumbosacral spinal orthosis or modified Boston brace can be used for low-grade slips and is recommended for 3–6 months.

Interventions such as epidural steroid injections may be helpful in treating the radicular symptoms. The medial branch provides innervation to the facet joint as well as the lamina, so a medial branch block or ablation may be helpful in treating axial pain.

Surgery is indicated in patients with intractable pain or progressive neurologic deficits, or those in whom symptoms are resistant to nonoperative measures. Decompression laminectomy, with or without fusion, or interspinous spacers have been shown to reduce pain associated with degenerative spondylolisthesis. Traumatic spondylolisthesis often requires surgery. The goal of surgery is to stabilize the spinal segment and decompress the neural elements.

The degree of recovery is dependent on the type and degree of spondylolisthesis. Young patients with low-grade slips tend to do well with conservative care. Patients with degenerative disease and those who undergo surgery often continue to have symptoms.

SPINAL STENOSIS

ESSENTIAL OF DIAGNOSIS

Back, buttock, or limb pain on standing or walking that is relieved with sitting.

Cross-sectional imaging shows narrowing of the spinal canal.

Spinal stenosis is a degenerative process that is one of the most common painful conditions of the elderly, causing symptoms in more than 1.2 million Americans. Stenosis (a term derived from the Latin for “narrow”) occurs in the spine when the central canal (neural foramen) decreases in size, causing compression of the neurovascular structures. The natural curvature of the spine plays an important role in the signs and symptoms of spinal stenosis. Any tube will naturally narrow when it is bent. In the spine, the lordosis of the cervical and lumbar segments is reduced in flexion, and increased with extension. Thus, activities that promote extension of the spine at these levels, such as standing, produce symptoms.

Degenerative disc disease results in posterior disc bulging, which may compress the ventral and lateral aspects of the thecal sac. Ligamentum flavum hypertrophy causes compression dorsally, whereas facet joint hypertrophy causes lateral recess and neuroforaminal stenosis. Spinal stenosis is often acquired, although congenital variations, such as shortened pedicles, may cause symptoms in younger patients (Table 31–4).

Neurogenic claudication is the quintessential chief complaint of the patient with lumbar spinal stenosis and is described as pain in the buttocks and lower limbs with standing and walking that is relieved with sitting. The classic “shopping cart sign,” in which the patient leans forward on a cart while in the market, is often reported. Patients may be able to differentiate the symptoms with certain activities. Walking uphill is often better tolerated than walking downhill or on flat surfaces. Likewise, patients may be able to tolerate riding an exercise bike better than walking on a treadmill. Patient with cervical spinal stenosis often have pain in the neck and upper limbs. In more severe cases they become myelopathic, reporting spasticity, weakness, loss of balance, or even bowel or bladder incontinence. Careful note of previous surgery should be made, as degeneration adjacent to the level of previous spinal fusion may lead to iatrogenic spinal stenosis.

Physical examination findings are dependent on the severity of disease, with many patients having unremarkable examinations. Changes such as a forward-flexed posture while standing and walking may be observed in the office. Range of motion in the spine may be diminished with extension. In patients with more severe disease, neurologic symptoms can be seen, such as motor weakness, sensory loss, and hyperreflexia in the case of cervical stenosis, and hyporeflexia in stenosis of the lumbar spine.

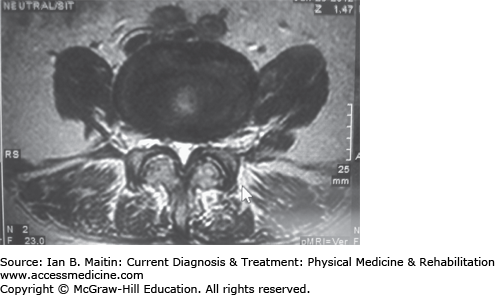

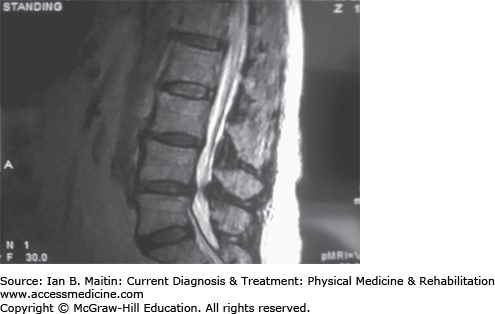

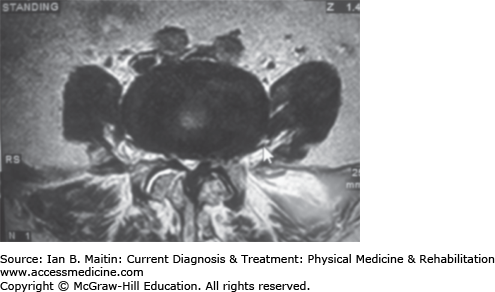

Imaging of the spinal canal is essential for diagnosis of spinal stenosis. MRI has become the gold standard as the ability to visualize soft tissue plays a major role in spinal stenosis. The availability of standing and seated MRI allows examiners to see how stenosis is related to posture (Figures 31–2, 31–3, 31–4, and 31–5). When MRI is unavailable or contraindicated, CT may be used, preferably with myelography. It has been suggested that an anteroposterior canal diameter of less than 10 mm, or a cross-sectional area of less than 100 mm2 defines spinal stenosis. A 50% reduction in canal diameter compared with adjacent levels also indicates spinal stenosis. Plain films offer little in terms of visualizing the central canal, although they may visualize the neural foramen. Flexion–extension views should be ordered to assess for dynamic instability.

Electrodiagnostic testing is not part of the routine workup for spinal stenosis, although paraspinal mapping electromyography (EMG) may be predictive.

Selective spinal nerve block may help differentiate neurogenic claudication from other causes of limb pain in patients with spinal stenosis. This may also help to isolate the most significant lesion in patients with multilevel disease on imaging.

For mild stenosis, over-the-counter pain medications (eg, acetaminophen and NSAIDs) may be useful. Muscle relaxants have little utility in treating neurogenic claudication. Neuropathic agents may improve symptoms in neuropathic pain, and gabapentin has been shown to improve pain and walking distance in patients with lumbar spinal stenosis. For patients with severe symptoms, opiates may provide the only means for relief, although special consideration is needed when prescribing potentially sedating medication to these patients, as they are already at increased risk for falls.

Physical therapy should be used in conjunction with other therapies as part of the comprehensive management of spinal stenosis. Attention should be given to stretching the tight ventral muscles of the core. A balanced strength program helps patients to maintain good posture and stand erect. Cardiovascular fitness provides the patient with endurance. Because spinal stenosis causes pain on walking, the use of a treadmill should be limited; however, the use of a stationary bike as well as a hand bike can be encouraged.

Rigid bracing may improve symptoms of lumbar spinal stenosis but is not recommended because it impairs mobility. Use of a flexible corset has been shown to be effective in increasing walking distance while it is worn, but there are no lasting benefits to the therapy once discontinued. Epidural steroid injections are useful in the treatment of neurogenic claudication. The use of a series (performed at regular intervals irrespective of the patient’s symptoms) of injections is not recommended, but the use of multiple injections throughout the course of treatment has been shown to provide durable and significant relief.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree