Skin/Soft Tissue Injury/Infection

River M. Elliott

Jonas L. Matzon

David R. Steinberg

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The human hand is of vital importance in interacting with surroundings, performing activities of daily living, and working. Because of the hand’s constant functional role, skin and soft tissue injuries to the hand are commonly encountered by primary care physicians, emergency medicine doctors, orthopedic surgeons, and hand surgeons. Patients often present to the physician after domestic, recreational, or industrial accidents, and the clinical presentation varies greatly depending on the event.

Hand injuries are frequently associated with trauma, and other major organ systems may be concurrently injured. Accordingly, the first step in evaluating a patient with a skin or soft tissue injury to the hand is assessing the patient’s overall condition and determining whether the available resources and setting will be sufficient for treatment of any associated major injuries. Depending on the severity of the injury, the primary and secondary trauma surveys (ABCDE: airway, breathing, circulation, disability, and environment) should be performed, and the patient should be triaged to an appropriate facility. Once the patient is stable, a thorough history that includes the time, place, mechanism, and nature of injury should be obtained. Time elapsed since the injury must be known to assess possible ischemia time, risk of infection, and time period for repair. Place of injury is a necessary information to determine likelihood of contamination. Mechanism of injury allows the practitioner to formulate an idea regarding the severity of tissue damage. Nature of the injury determines the amount of surrounding tissue that was concomitantly injured. Possible types include lacerations, crush injuries, burn injuries, high-pressure injection injuries, and chemical injuries, and each of which has a different treatment algorithm.1 When tendon injuries are suspected, it is helpful to know how the hand and fingers were positioned during the injury (i.e., was the patient’s hand open or closed), as this information can help determine the position of the injured tendon relative to the opening in the skin. Other key components of the history include handedness, previous injuries to the extremity, preinjury functional capacity of the extremity, occupation, any pertinent past medical history such as immunosuppression, medical comorbidities, allergies, date of last tetanus shot, and time since the patient last ate or drank.

CLINICAL POINTS

Various types of accidents may result in injury.

Injuries to the hand are the most common cause for emergency room visits.

Injuries range in severity.

A thorough history and exam are necessary.

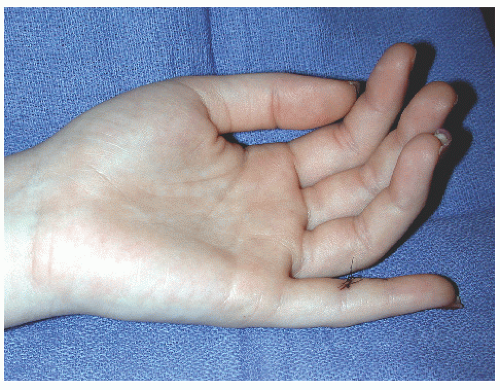

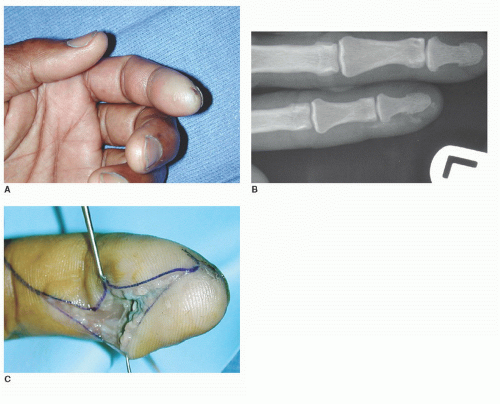

PHYSICAL FINDINGS

The presentation of skin and soft tissue injuries of the hand vary greatly, depending on the nature and severity of the injury. When performing a physical examination, the first task is to thoroughly and completely inspect the hand. Special attention should be paid to the size and complexity of lacerations, exposure of “white structures” (tendon, bone, or neurovascular bundle), any deformity that causes deviation from the normal resting posture of the hand, any areas that are actively bleeding or ischemic, any nail bed injury, and any obvious foreign bodies. Next, a full neurovascular examination evaluating the

median/anterior interosseous, radial/posterior interosseous, ulnar, and digital nerves should be performed. Capillary refill should be assessed in the nail beds or pulp of each digit. Pale color or refill >2 seconds indicates arterial insufficiency and ischemia, while overly brisk refill in the presence of swelling and purple skin discoloration are stigmata of impaired venous outflow. Neuropathy should be assessed in relation to open wounds or areas of crush to determine whether there is a neuropraxia or neurotmesis. If active bleeding exists, direct pressure should be exerted over the area to tamponade the bleeding. Never attempt to clamp or ligate a bleeding vessel as adjacent nerves may be injured. Finally, isolated active and passive range of motion should be tested at all of the joints of the hand to assess tendon injury. If tendon injury is suspected, do not attempt to test motion against resistance, as this may rupture an incompletely lacerated tendon.

median/anterior interosseous, radial/posterior interosseous, ulnar, and digital nerves should be performed. Capillary refill should be assessed in the nail beds or pulp of each digit. Pale color or refill >2 seconds indicates arterial insufficiency and ischemia, while overly brisk refill in the presence of swelling and purple skin discoloration are stigmata of impaired venous outflow. Neuropathy should be assessed in relation to open wounds or areas of crush to determine whether there is a neuropraxia or neurotmesis. If active bleeding exists, direct pressure should be exerted over the area to tamponade the bleeding. Never attempt to clamp or ligate a bleeding vessel as adjacent nerves may be injured. Finally, isolated active and passive range of motion should be tested at all of the joints of the hand to assess tendon injury. If tendon injury is suspected, do not attempt to test motion against resistance, as this may rupture an incompletely lacerated tendon.

Different classification systems have been developed to better categorize injuries. Rank et al.2 classified wounds as tidy or untidy. Tidy wounds incorporated simple cuts in the skin, a slicing injury with loss of soft tissue, a guillotine amputation, and a simple wound involving a tendon or nerve injury. Buchler and Hastings3 developed a classification system that involved all of the relevant structural systems such as bones, joints, extrinsic extensors, extrinsic flexors, intrinsics, arteries, veins, skin, and nails. Injuries were classified as isolated if they involved only one relevant structural system or combined if they involved two or more systems.3 Finally, Gustilo and Anderson4 proposed the widely accepted open fracture classification system. Type I fractures have a clean wound <1 cm, type II fractures have a 1- to 10-cm wound without extensive soft tissue damage, and type III fractures have either a wound >10 cm or extensive soft tissue damage. Type III injuries are further subdivided into IIIA fractures that have adequate soft tissue coverage; IIIB fractures that demonstrate periosteal stripping, bone exposure, and massive contamination; and IIIC fractures that have arterial injury requiring repair.4

In crush injuries to the hand, the physician should have a high index of suspicion for possible compartment syndrome (elevated intracompartmental pressures interfering with microcirculation to the nerve and muscle). Early findings include a tense, swollen hand; pain out of proportion to other objective findings; and pain with passive motion (specifically passive adduction and abduction) of the digits. Immediate referral to a specialist and/or measurement of compartment pressures is indicated.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree