Shoulder Instability (Multidirectional and Unidirectional)

Fotios P. Tjoumakaris

Bradford S. Tucker

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Instability of the glenohumeral joint is a common cause of disability and pain in the adolescent and young adult population. Patients can present to the clinician with a variety of symptoms, and in many instances, the description of instability can be quite vague. The main presenting symptoms are usually pain; varying degrees of instability or the sensation of joint subluxation; and occasionally, transient neurologic symptoms.1 With unidirectional anterior instability, the patient can typically localize the pain or instability to the position of shoulder abduction and external rotation and often can remember a specific event that may have brought on the symptoms. Unidirectional instability tends to afflict males more commonly than females and typically is the result of significant trauma to the shoulder. These patients may have had a dislocation in the past that required treatment in the form of an emergent closed reduction by medical personnel. With multidirectional instability, the classic presenting complaint is pain, and patients may experience symptoms during daily activities with seemingly insignificant provocation.2 Patients with multidirectional instability of the shoulder are usually female and involved in athletic activities that repetitively cycle the glenohumeral joint (swimming, volleyball, etc.).

CLINICAL POINTS

The condition is a common cause of disability and pain in adolescents and young adults.

Unidirectional instability usually is more common in males and traumatic in origin.

Multidirectional instability usually is more common in females and atraumatic in origin.

PHYSICAL FINDINGS

The physical examination of patients who are suspected of having instability can be deceiving. It is often advisable to begin the examination away from the shoulder to gauge the cooperation of the patient as well as to detect any concomitant pathology that may be contributing to or causing the shoulder symptoms. The cervical spine should be examined first to rule out any abnormalities, such as radiculopathy or spondylosis that may be causing referred pain to the shoulder. A generalized assessment of the patient’s ligamentous laxity can then be ascertained to determine if this may be a contributing factor to the instability. This is assessed by the presence

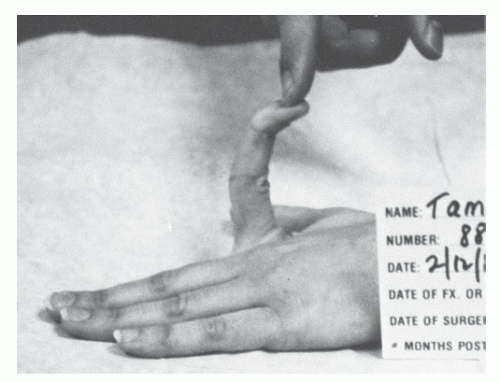

of elbow hyperextension, metacarpophalangeal joint hyperextension, leg hyperextension or recurvatum, patella subluxation, and the ability of the abducted thumb to reach the forearm (thumb to forearm test) (Fig. 40-1). The presence of any or all of these tests may indicate an underlying connective tissue disorder such as Marfan or Ehlers-Danlos syndromes. This is vital information, as patients with these disorders are known to do poorly with surgical treatment.3

of elbow hyperextension, metacarpophalangeal joint hyperextension, leg hyperextension or recurvatum, patella subluxation, and the ability of the abducted thumb to reach the forearm (thumb to forearm test) (Fig. 40-1). The presence of any or all of these tests may indicate an underlying connective tissue disorder such as Marfan or Ehlers-Danlos syndromes. This is vital information, as patients with these disorders are known to do poorly with surgical treatment.3

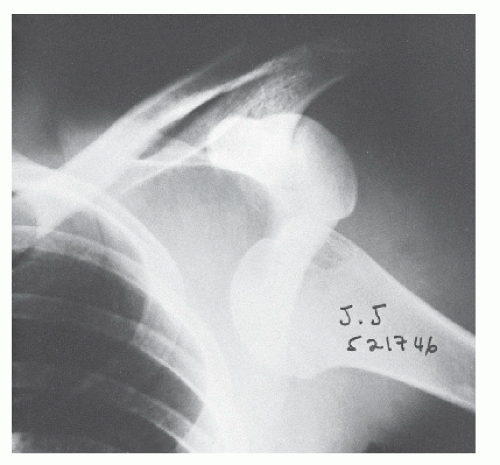

The patient should be inspected for muscle atrophy from both the front and back. In a relaxed patient, there may be an abnormal contour of the deltoid such as squaring, or the acromion may be prominent due to inferior subluxation of the involved shoulder1 (Fig. 40-2). Muscle testing and a complete neurovascular examination of the upper extremity should be assessed and compared with the contralateral extremity. Nerve injuries (primarily those involving the axillary nerve) have been identified in 32% to 65% of patients with dislocations and are more common in older patients and those patients who sustain a concomitant fracture.4 Range of motion of the shoulder is performed both actively and passively and compared with the contralateral extremity.5 Strength deficits can be a result of pain during the examination or a sign that concomitant rotator cuff pathology exists. In patients over the age of 40, a traumatic dislocation may often be accompanied by acute rupture of the rotator cuff tendon; however, younger patients rarely have this concomitant injury, as capsular and labral pathology are more prevalent in this population. A range-of-motion deficit on examination may occasionally be due to the patient having been placed in a sling after a traumatic event. In the final portion of the examination, instability is assessed. The clinician should bear in mind that examination of the asymptomatic shoulder can serve as a control and may help to gain confidence from the patient prior to examination of the symptomatic extremity. In addition, it should be noted that laxity is not a synonym for instability; reproduction of symptoms during provocative maneuvers is key to confirming the diagnosis.

Inferior laxity is first assessed by applying traction with the arm at the side (sulcus test). A positive test is indicated by inferior translation of 1 to 2 cm with noticeable dimpling below the anterolateral acromion (sulcus sign). Anterior and posterior laxity is then assessed with the load and shift test in the seated or supine position. The examiner grabs the proximal humerus and applies a gentle compressive force on the humeral head into the glenoid fossa while the free hand supports the elbow. The humeral head is then translated both anteriorly and posteriorly as far over the glenoid rim as possible. Medial translation of the head with this maneuver typically indicates that subluxation has occurred. The amount of subluxation is documented and compared with the uninvolved shoulder. Reproduction of the patient’s symptoms with this maneuver is key to establishing a diagnosis of multidirectional instability.6 Patients with unidirectional instability in the anterior plane will typically demonstrate anxiety as their shoulder is abducted and externally rotated while in the supine position (apprehension sign) (see Fig. 35-17). This maneuver reproduces the sensation of an impending dislocation. Relief of apprehension with a posteriorly directed force on the humeral head in this same position is also a confirmatory test for anterior instability (relocation test) (see Fig. 35-18).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree