Musculotendinous units of the rotator cuff and biceps.

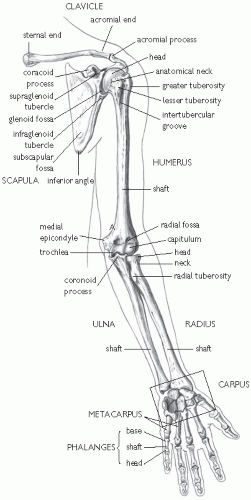

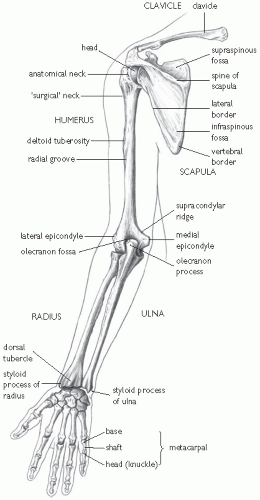

Bony landmarks of the humerus, scapula, and clavicle.

Four joints of the shoulder.

The subscapularis is located anteriorly on the scapula.

The supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and the teres minor are located posteriorly on the scapula.

All are closely associated with the glenohumeral capsule, as is the biceps tendon.

Primary function of the rotator cuff is to position the humeral head in the glenoid allowing larger muscles to provide necessary power.

Greater tuberosity of the humerus:

Insertion site of the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and teres minor tendons.

This prominence is often associated with impingement.

When testing for impingement on physical exam most tests attempt to force the greater tuberosity under and against the acromion and the coraco-acromial ligament, thus catching or ‘impinging’ the subacromial structures.

The bicipital groove is a palpable indentation immediately medial and anterior to the greater tuberosity of the humerus:

It houses the tendon of the long head of the biceps.

It is easily identified if the humerus is alternately internally and externally rotated, while palpating this area.

There is a retinaculum that holds the biceps tendon in place.

On the anterior and inferior border of this groove is the lesser tuberosity, the insertion site of the subscapularis.

The glenohumeral, acromioclavicular, and the sternoclavicular joints:

The latter two may have a fibrocartilagenous disc present within the articulation.

As with all true joints, they are susceptible to various arthritides and trauma.

The glenohumeral joint sacrifices the bony and ligamentous stability of other joints for increased range of motion.

The primary stabilizers of the joint are the musculotendinous complex of the rotator cuff and joint capsule, including the labrum.

The subacromial bursa:

Located immediately inferior to the acromioclavicular joint and superior to the glenohumeral joint.

It is often involved in impingement syndrome.

Injection of local anesthetic into this bursa with eradication of symptoms is the basis of the impingement test.

The subdeltoid bursa: located inferior to the deltoid tendon on the lateral shaft of the humerus.

The subscapular bursa: located between the joint capsule and the tendon of the subscapularis muscle.

The subcoracoid bursa: located between the joint capsule and the coracoid process of the scapula.

What is/are the predominant symptom(s)?

Chief complaints may range from pain to instability to weakness. If pain is the predominant symptom, ask the patient to describe the quality of the pain, its location, and quantify the severity of the pain on a scale from 1 to 10. This helps you assess the results of treatment.

How long have the symptoms been present? How have they developed or how have they changed? Have you had similar symptoms in the past? Was there any history of trauma (recent or remote)?

Where did the pain begin and has it changed in its location? Does the shoulder hurt at night? What position do you normally sleep in? Are there certain positions or activities that bother it more than others?

What is your job? What are your hobbies or sports activities?

Injuries due to over-use are often seen in workers who have to work overhead frequently. They are especially susceptible to impingement syndrome, subacromial bursitis, and acromioclavicular problems. Certain sports have an increased incidence of shoulder injuries, especially volleyball, swimming, the overhead throwing sports, racquet sports, hockey, wrestling, weightlifting and body-building.

What has been done so far for treatment? Have there been any prior injuries or surgery to either of the shoulders?

Do you have any problems with neck pain? Is there any pain radiating into the shoulder or down the upper extremity? Do you have any associated abdominal pain, or chest pain? Is there a history of weight loss, fatigue, or fevers?

Exposure (including shoulder blades): women may use bra and/or tie gown around upper chest with arms out.

Muscle atrophy:

Biceps atrophy may be due to musculocutaneous nerve injury.

Scapular winging may be due to long thoracic nerve injury.

Asymmetry:

A pronounced biceps may be due to rupture of the long head of the biceps tendon, giving a ‘Popeye’ defect.

Prominence of the scapular spine may be due to nerve palsy in young patients, or a long-standing rotator cuff tear in older patients.

Screen for referred pain:

Cervical spine.

Cardiopulmonary.

Abdominal.

There are nine movements described in the shoulder:

Abduction (normal 180°).

Adduction (normal 45°).

Flexion (normal 180°).

Extension (normal 45°).

Internal rotation (IR, normal 70°).

External rotation (ER, normal 75°).

Protraction, retraction, and elevation.

Assess smoothness of the scapulohumeral and scapulothoracic movement, and test for a ‘painful arc’ which may suggest impingement, rotator cuff problems, or labral tears.

Impingement pain is usually from 90-120° of abduction.

Restricted or painful IR at 90° of abduction may also signify shoulder impingement.

IR is best observed with Apley’s (behind the back) scratch test: at least 55° of IR is required to perform this manoeuvre, and range of motion can be quantitated according to the level of the thoracic or lumbar spine that they can reach (T7 is at the inferior angle of the scapula) for comparison after treatment.

Table 17.1 Palpation points | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Table 17.2 Shoulder (glenohumeral) joint: movements, principal muscles, and their innervation1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Located between the scapula and the thoracic wall.

May be multiple small bursae.

May become inflamed with over-use, causing ‘snapping scapula’.

Often difficult to diagnose.

May need to managed surgically if persistent symptoms.

Any of these areas may be injured with compression or stretching of the brachial plexus.

Because of the high incidence of anterior shoulder dislocations, the most likely peripheral nerve to be damaged is the axillary nerve.

Other peripheral nerves that are likely to be damaged include the suprascapular, musculocutaneous, and the long thoracic nerves.

Shoulder pain is the second most common musculoskeletal complaint seen by practitioners: 1.2-2.5% of attendances in primary care.

Rotator cuff lesions (65%).

Pericapsular soft tissue pain (11%).

Acromioclavicular joint pain (10%).

Mild trauma.

Acute onset.

Over-use problems.

Early presentation.

Diabetes mellitus.

Cervical spondylolysis.

Radicular symptoms.

Advancing age.

Involvement of the dominant extremity.

An inherently less stable joint.

The fact that we ‘abuse’ the joint with repetitive work activities and participate in sports that push the limits of the joint.

Trauma.

Acute over-use.

Cervical nerve root compression.

Patients below the age of 45 often have a biomechanical cause to their problem, such as instability or tendinopathy..

Those older than 45 are more likely to have degenerative conditions, such as osteoarthritis or rotator cuff tears.

Evaluate the patient for adhesive capsulitis if there is a history of diabetes mellitus, progressive pain, and loss of motion.

From grade I, with less than 50% subluxation of the humeral head beyond the glenoid fossa, to grade IV, which is a complete dislocation.

If a patient lands on the posterior aspect of the shoulder during a fall forcing the humeral head anteriorly on the glenoid or if there is forced ER, while the upper extremity is abducted.

The pressure of the anterior glenoid on the posterior humerus during dislocation may cause a small compression fracture or divot on the posterior humeral head known as a Hill—Sach’s lesion.

While the humeral head is being forced anteriorly, the anterior capsule may tear the labral cartilage away from the underlying glenoid, termed a Bankart lesion, worsening the anterior instability.

Patients usually present with pain in the anterior and lateral shoulder.

They will often complain of an inability to move the shoulder without significant pain and, in many cases, ‘know’ it is dislocated.

With an acute anterior dislocation, the acromioclavicular joint may be prominent on exam, and the shoulder appears ‘sunken’.

Patients will hold the arm in a partially abducted and externally rotated position.

If the shoulder has relocated, they may have signs of instability on examination, or a positive Speed’s test or apprehension test.

Diagnosis of dislocation is usually obvious on inspection.

May be identified by X-ray evaluation, particularly the scapular Y view.

A thorough neurovascular exam should be documented in all cases.

Immediate reduction preferably after evaluation by X-ray.

Surgical intervention after the first dislocation is unusual, but may be appropriate in:

High performance athlete at risk for repeated dislocations (football, hockey, or other collision sport).

Worsening symptoms of instability despite conservative treatment.

Consider a rotator cuff tear in the first time dislocater who is older than 45 years of age.

There is a trend now towards immobilization in ER for a period of time, to allow tissues to heal in a more physiologic position.

Followed by appropriate physiotherapy.

after an anterior blow to the shoulder. A small avulsion of the posterior glenoid labrum may occur resulting in a reverse Bankart lesion.

Patients with posterior dislocations will present with the arm in IR, and held close to the thorax.

They are generally unable to abduct or externally rotate the shoulder.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree