Septic Arthritis of the Hip

David A. Spiegel

B. David Horn

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Septic arthritis of the hip has an incidence of approximately 1/100,000 and is more common in younger children. Prompt diagnosis, surgical drainage, and intravenous antibiotics are the mainstays of treatment for hip sepsis and are vital in preventing complications.1,2

Most patients with septic arthritis of the hip are infected from a hematogenous route. Transient bacteremia may result in organisms settling in the subsynovial layer of the hip. This tissue is unique in that it does not contain a basement membrane, so bacteria can easily gain access into the joint. A second route of infection is direct spread from a proximal femoral metaphyseal osteomyelitis. Other joints in which the metaphysis is intraarticular include the radial neck, proximal humerus, and distal fibula. In addition, neonates and infants have blood vessels that transverse the physis, and these transphyseal vessels may be a route of infection into the hip joint. The physis becomes an effective barrier to the direct spread of a proximal femoral osteomyelitis after approximately 18 months of age.

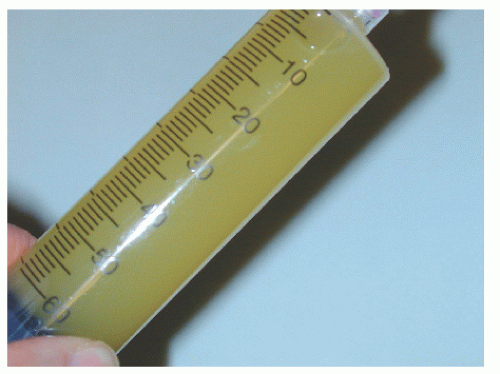

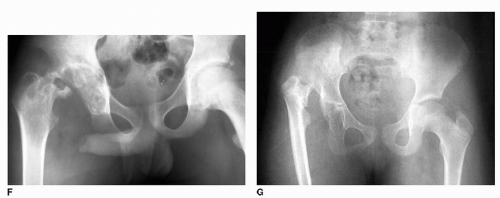

Regardless of the exact mechanism of introduction, the bacteria multiply rapidly and incite an inflammatory response. Polymorphonuclear cells migrate into the joint, and an effusion develops. A tense effusion may compromise the blood supply to the femoral head, highlighting the importance of prompt diagnosis and drainage. Damage to the proximal femur and the acetabulum may be due to (a) the destructive effects of proteolytic enzymes (liberated by bacteria) on articular cartilage and (b) decreased perfusion to the femoral head from increased intracapsular pressure, which may cause avascular necrosis (Fig. 59-1). In addition, the infection triggers a monocyte-mediated inflammatory cascade, leading to the release of various proteases by synovial and cartilage cells, which may damage the hyaline articular cartilage.

The differential diagnosis is large and includes transient synovitis, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, Lyme disease, psoas abscess, pelvic osteomyelitis, septic sacroiliitis, Legg-Calve-Perthes disease, and leukemia or other neoplasms.3,4,5 Risk factors for septic arthritis include young age, male gender, reduced immune function (prematurity, sickle cell disease, others), respiratory distress syndrome, and umbilical artery catheterization.

CLINICAL POINTS

Infection may be due to bacteremia or the spread of a metaphyseal osteomyelitis.

A high index of clinical suspicion is required to make an early diagnosis.

A delay in diagnosis and/or treatment may result in irreversible damage to the joint.

Hip sepsis should be treated as a surgical emergency.

PHYSICAL FINDINGS

A high index of clinical suspicion is required to make an early diagnosis of septic arthritis of the hip. While many children with septic arthritis of the hip will present acutely with systemic signs or symptoms, such obvious signs of infection may be absent during early phases of the disease or routinely in neonates and infants. There may also be a history of a prodromal infection, such as streptococcal pharyngitis or otitis media. Antibiotics given for these conditions may also mask the early presentation

of septic hip. In infants, an early clinical sign may be irritability during diaper changes. Infants and toddlers may exhibit general irritability, may have a decreased appetite, and may cease to crawl or ambulate. Older children may complain of pain in the groin, thigh, or knee (referred pain). Patients with acetabular or pelvic osteomyelitis may have a variety of symptoms including buttock pain, abdominal pain, and low back pain.

of septic hip. In infants, an early clinical sign may be irritability during diaper changes. Infants and toddlers may exhibit general irritability, may have a decreased appetite, and may cease to crawl or ambulate. Older children may complain of pain in the groin, thigh, or knee (referred pain). Patients with acetabular or pelvic osteomyelitis may have a variety of symptoms including buttock pain, abdominal pain, and low back pain.

Patients with an effusion will frequently hold the hip in abduction, flexion, and external rotation, which maximizes the volume of the hip joint. Any motion of the hip usually produces pain, and patients may guard against any attempted motion of the hip. In contrast to other causes of an irritable hip in which discomfort may be elicited at the extremes of motion (especially rotation), patients with septic arthritis commonly have pain with “short arc” motion within the mid range of joint motion. Palpation may reveal tenderness over the anterior aspect of the hip. Patients with a psoas abscess will have relief with the hip in flexion (relaxes muscle) and pain with extension of the hip (stretches muscle).4 A psoas abscess may also spread distally under the inguinal ligament and secondarily infect the hip.4 Patients with septic sacroiliitis often have pain in more than one area (back, hip, buttock, abdomen) and will often have significant discomfort with passive flexion/abduction/external rotation, pain with lateral pelvic compression, and tenderness with direct palpation over the sacroiliac joint.5

Differential Diagnosis

Transient synovitis of the hip

Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree