Sepsis of the Shoulder Girdle

John L. Esterhai Jr.

INTRODUCTION

This chapter will address the issues of diagnosis and management of infections involving the shoulder. The major focus is on primary pyarthrosis of the glenohumeral joint. We will also discuss shoulder sepsis associated with osteomyelitis, septic subacromial bursitis, soft tissue infection, and infections involving the sternoclavicular and acromioclavicular joints. No attempt has been made to specifically include Lyme disease, brachial plexus neuritis, or nonsuppurative (viral, fungal, or mycobacterial) infections, which may be part of the differential diagnoses of an infected shoulder joint. For the purpose of presentation, the topic is subdivided into pathophysiology, specific clinical entities, evaluation techniques, treatment, authors’ preferred treatment, prognosis, and directions for further study.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Septic arthritis of the shoulder is an inflammation of the glenohumeral joint involving one or more foreign pathogens that cause, or are suspected of causing, the inflammation. These pathogens can be bacteria, viruses, fungi, or parasites, and can gain access to the joint through a number of different means. The defense mechanisms of the host and the properties of the invading organism play an important part in the pathophysiology of septic arthritis, as does the premorbid condition of the joint. Chronic arthritis and trauma resulting in soft tissue damage can predispose a joint to infection.

Joint sepsis may be classified according to pathogenesis. There are three basic mechanisms: direct inoculation, contiguous spread from adjacent osteomyelitis, and hematogenous dissemination.

Hematogenous Septic Arthritis

Hematogenous dissemination from another organ system, such as skin breakdown, urinary system infections, or pneumonia, is

the most common. In over 50% of the patients with intraarticular sepsis, there is a positive blood culture.47 Goldenberg and Cohen isolated the pathogen from a distant focus in 50% of the cases.

the most common. In over 50% of the patients with intraarticular sepsis, there is a positive blood culture.47 Goldenberg and Cohen isolated the pathogen from a distant focus in 50% of the cases.

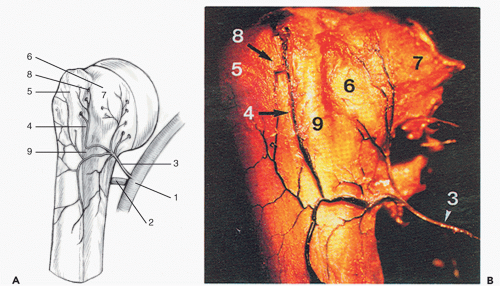

Similar to the findings reported by Chung in the hip,18 in the shoulder, branches of the suprascapular and subscapular arteries, along with the anterior and posterior circumflex humeral arteries, form an extracapsular arterial ring, which supplies the proximal humerus (Fig. 35-1A,B).41 This anastomosis gives off branches that penetrate the capsule and form an intraarticular synovial ring.58 This has been termed the “transition zone” and is located between the synovium and the articular surface.102 It is in this area that the arterioles loop acutely toward the periphery, creating a low-flow state, making the area more susceptible to receptor-specific interaction of the pathogen and the cell surface.

Spontaneous shoulder sepsis is the result of joint invasion during bacteremia. Septic arthritis has been shown to occur in experimental animals when bacteremia is created.76 The abundance of the synovial vasculature and the absence of a basement membrane between the endothelial cells make synovial joints vulnerable to seeding by bacteria. Furthermore, most patients with hematogenous nongonococcal bacterial arthritis have at least one underlying chronic medical risk factor. These factors may be local, such as prosthetic and metallic implants, or they may be systemic, such as cancer, cirrhosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and intermittent bacteremic episodes from intravenous drug abuse or indwelling catheters48 (Table 35-1).

Direct Inoculation

Direct inoculation may be traumatic or iatrogenic. Repeated injections, arthroscopy, and open surgical procedures, such as rotator cuff repair and arthroplasty, have been shown to be associated with pyarthrosis of the shoulder. The incidence of infection following intraarticular steroid injection is extremely small. Hollander reported 18 infections in 250,000 injections,63 and Gray et al. found only two cases complicating 100,000 injections50 The advent of sterile disposable needles and syringes and adherence to meticulous aseptic technique has helped lessen the risk. The existence of foreign bodies around the joint or devitalized bone from trauma can provide a nidus for adhesion and colonization by bacteria.52,56,58 This nidus allows a glycocalyx biofilm to be expressed by the bacteria, which contributes to antibiotic resistance and limits the effectiveness of the immune response of the host.

Septic Arthritis from Contiguous Osteomyelitis

Osteomyelitis is most often hematogenous in origin and, in particular, is a disease of young children and the elderly. Hematogenous osteomyelitis commonly involves the metaphyseal area of rapidly growing long bones, usually occurring in the hip and knee.84 When septic arthritis results from a contiguous infection such as osteomyelitis, it spreads from the bone to the synovium, then to the joint space. This happens most often in infancy, when there is a vascular anastomosis between the epiphysis and the metaphysis. Studies conducted on the proximal femur by Trueta115 showed a direct vascular communication between metaphyseal arterioles and the epiphyseal ossicle before 8 months of age. This allows a direct hematogenous communication between an osteomyelitis of the metaphysis and the adjacent joint synovium.29,87 Between the ages of 8 and 18 months, the last vestiges of the nutrient artery system close down at the growth plate. The open physis at this point provides an effective barrier to the spread of infection to the joint by obliterating this vascular anastomosis.109 This situation is analogous in the proximal humerus.

TABLE 35-1 Risk Factors in Bacterial Arthritis | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

At skeletal maturity, there is once again a direct osseous connection between the metaphysis and epiphysis, secondary to closing of the growth plate and reestablishment of anastomoses between the metaphyseal and epiphyseal arterioles.3 Therefore, infection of the proximal humeral metaphysis may extend to the epiphysis and the joint through the haversian system and Volkmann canals. In addition, the proximal 10 to 12 mm of the metaphysis of the proximal humerus is intraarticular, giving the pathogens of metaphyseal osteomyelitis direct access to the synovium.

Synovial Tissue and Infection

The anatomy of the shoulder joint is intricately involved in the pathogenesis of sepsis. All synovial joints contain synovial fluid, which can act as an excellent growth medium for bacteria and have a relative lack of immunologic resistance.36 Type B synoviocytes are weakly phagocytic but in most cases are able to limit and clear a blood-borne bacterial infection.6 Therefore, there must be an imbalance between normal synovial cell function and the invading bacteria for an intraarticular infection to develop.

Synovial tissue is relatively resistant to infection.6 Examination of joints in which experimental septic arthritis has been produced reveals infrequent colonization of the synovium.119 Receptors for collagen have been found on several strains of Staphylococcus aureus. It may be a lack of ligands or a functional host resistance mechanism that helps to prevent synovial colonization.58

Microscopic examination of the synovium shows that it is relatively thin in the area of the transition zone, rarely being more than three or four cell layers thick. The synovial capillaries are superficial, making them more susceptible to trauma. The lack of epithelial tissue in the synovium, and thus the lack of a basement membrane, means that there is no structural barrier to the spread of bacteria from the synovium to the joint. Thus, transient bacteremia and trauma causing intraarticular hemorrhage can play a role in the pathogenesis of septic arthritis.58

Bacterial Adhesion

Integral to the pathogenesis of infectious arthritis is the preferential colonization of bacteria to articular cartilage, traumatized bone, or biomaterials that are not integrated with healthy tissues composed of living cells and extracellular matrix proteins.10,56,58,105,110 Bacterial adhesion involves either very specific receptor-ligand or receptor-lectin-ligand chemical interaction or nonspecific interaction based on charge-related, hydrophobic, and extracellular polysaccharide-based interactions.55 S. aureus has receptors for types I and II collagen,108 fibrinogen, laminin, fibronectin, thrombospondin, bone sialoprotein, and heparin sulfate.106 Many factors influence the adherence properties of bacteria, including (a) the surface energy and surface-free energy of the bacteria and biomaterial, (b) the extracellular components of the bacteria, (c) the bacterial interaction in mixed infections, (d) the host immune system, and (e) the extracellular matrix.34

All natural, biologic surfaces, with the exception of teeth and articular cartilage, are protected by the epithelium, endothelium, or periosteum, which decreases bacterial adhesion by desquamation or by the presence of host extracellular polysaccharide molecules. S. aureus is the natural colonizer of cartilage and collagen, because it has specific surface-associated adhesins26 for sites on collagen, not for enamel. Although the colonization of teeth by Streptococcus mutans is a natural symbiotic process that can be slowly destructive, the bacterial colonization of articular cartilage is unnatural and is rapidly destructive.42,58 Bacterial adherence is characterized by the production of an extracellular exopolysaccharide, within which the bacteria aggregate and multiply. Bacteria in aquatic environments grow predominantly in these biofilm-enclosed microcolonies adherent to surfaces.53 Following initial colonization, the microcolonies develop coherent and continuous biofilms36 that contain more than 99.9% of the bacteria in thick layers, within which they are protected from antibacterial agents24,53,54 and the host immune defenses. This glycocalyx allows the bacteria to modify their local environment, limiting both the specific and the nonspecific arms of the immune response. Bacteria adherent to bone, methyl methacrylate, orthopedic devices, and surrounding tissue are harder to completely eradicate until the infected tissue and biomaterial are removed. Not infrequently, the infections are polymicrobial and difficult to culture adequately, unless special techniques are used.44,47,52,54,55

Microbiology

Patient age and host states help predict the bacterial cause of septic arthritis. Those organisms that frequently cause bacteremia in certain age groups are usually the infecting organisms, since joint sepsis is most commonly caused by hematogenous seeding. However, certain organisms, such as Neisseria gonorrhoeae and S. aureus, seem to have an avidity for the synovium, causing septic arthritis out of proportion to their incidence of bacteremia.109 S. aureus is the most common cause of adult,

nongonococcal bacterial arthritis, occurring in up to 50% of patients.74 Ward and Goldner121 noted 77% of infecting organisms to be Gram positive, of which 46% were S. aureus. Propionibacterium acnes is an anaerobic, Gram-positive bacillus that is found in lipid-rich areas, such as hair follicles and sebaceous glands, and in moist areas, such as the axilla. Although it is rarely the causal organism in other large joint infections, P. acnes has frequently been reported as the offending pathogen in shoulder sepsis and should not be dismissed as a skin contaminant. Joint infections with Gram-negative bacilli have been increasing in incidence, ranging from 5% to 30% of all shoulder infections.33,40,74,113 They most often occur in patients with intravenous drug abuse, malignancy, diabetes, immunosuppression, or hemoglobinopathy.109 Escherichia coli and Proteus species are common infecting Gram-negative organisms from the urinary tract, and occur in patients who are not intravenous drug abusers. Although Pseudomonas and Serratia are the common organisms in intravenous drug addicts, the incidence of S. aureus in this population has been increasing.5,11,33 Streptococcus pneumoniae is the most common organism in patients with chronic alcoholism and hypogammaglobulinemia.85 Polymicrobial infections of the shoulder occur in 5% to 15% of patients, often associated with an extraarticular polymicrobial infection or penetrating trauma, especially in immunocompromised patients.95

nongonococcal bacterial arthritis, occurring in up to 50% of patients.74 Ward and Goldner121 noted 77% of infecting organisms to be Gram positive, of which 46% were S. aureus. Propionibacterium acnes is an anaerobic, Gram-positive bacillus that is found in lipid-rich areas, such as hair follicles and sebaceous glands, and in moist areas, such as the axilla. Although it is rarely the causal organism in other large joint infections, P. acnes has frequently been reported as the offending pathogen in shoulder sepsis and should not be dismissed as a skin contaminant. Joint infections with Gram-negative bacilli have been increasing in incidence, ranging from 5% to 30% of all shoulder infections.33,40,74,113 They most often occur in patients with intravenous drug abuse, malignancy, diabetes, immunosuppression, or hemoglobinopathy.109 Escherichia coli and Proteus species are common infecting Gram-negative organisms from the urinary tract, and occur in patients who are not intravenous drug abusers. Although Pseudomonas and Serratia are the common organisms in intravenous drug addicts, the incidence of S. aureus in this population has been increasing.5,11,33 Streptococcus pneumoniae is the most common organism in patients with chronic alcoholism and hypogammaglobulinemia.85 Polymicrobial infections of the shoulder occur in 5% to 15% of patients, often associated with an extraarticular polymicrobial infection or penetrating trauma, especially in immunocompromised patients.95

Incidence

The incidence of shoulder sepsis is increasing as the population ages and the prevalence of chronic, debilitating disease increases.74,113 Currently, primary shoulder sepsis accounts for 10% to 15% of all joint infections, whereas the hip and the knee account for 20% to 25% and 40% to 50%, respectively.33 Septic arthritis of the shoulder is a rare occurrence in the young, immunocompetent person. More frequently, it is a disease of the elderly.118 Most patients have chronic, systemic, immunocompromising conditions such as diabetes mellitus, blood dyscrasias, renal failure, malignancy, and malnutrition.34,47,74,121 Local factors also play a role in some patients, such as indwelling catheters, intravenous drug use, prior joint disease (rheumatoid or osteoarthritis), trauma, bursitis, or radiation therapy.34,48,109 Ward and Goldner reported that 74% of 27 adults with septic arthritis of the shoulder had some systemic condition causing immunocompromise or some type of local tissue abnormality. In 52% of the patients, both were present.121

CLINICAL ENTITIES

Natural History of Septic Arthritis

Studies conducted in animals have demonstrated that direct joint inoculation with bacteria is followed by synovial, bone, and cartilage changes within a matter of hours. Experiments have been performed on mice, rats, rabbits, chickens, and hamsters, and most have utilized direct joint inoculation. Septic arthritis caused by S. aureus in a rabbit model displays two processes acting simultaneously. The synovium becomes inflamed and hypertrophies within minutes of infection, with an influx of polymorphonuclear cells. This develops into an invading pannus, eroding and undermining the articular cartilage. Bacteria can be identified in and extruded by the pannus, thus maintaining the inflammatory reaction and lysosomal discharge.94 Within 3 hours, a purulent exudate is observed, and within 24 hours multiple abscesses are seen. By day 5, synovial inflammation is so aggressive that there is extension below the cartilage interface, causing erosion and loosening in this area.

Simultaneously, by day 2, progressive loss of glycosaminoglycan occurs, as observed by a loss of safranin staining. This is most pronounced in the marginal areas near the leading edge of the pannus. The degradation of cartilage occurs through bacterial endotoxin, prostaglandins, and cytokine-mediated events that invoke a host inflammatory response and a release of destructive enzymes by synoviocytes and leukocytes.34 Total glycosaminoglycan depletion occurs by 14 days, and the protein-polysaccharide-depleted cartilage is susceptible to degradation by collagenases released by the lysosomes.94,122 The predominant cytokine is interleukin-1 (IL-1), which is released by synovial macrophages and circulating monocytes. IL-1 has been shown to inhibit chondrocyte proliferation and decrease expression of type II and X cartilage, making the articular cartilage more friable and susceptible to bacterial adhesion. Bremell et al., in their studies on septic arthritis in rats, noted the importance of CD4* T lymphocytes expressing IL-2 receptors, indicating activation. Deletion of T lymphocytes downgraded the intensity of infection, indicating a pathogenic role.12

If infection remains untreated for 7 to 10 days, cartilage fissuring and a decrease in height occur, most commonly involving the weight-bearing areas. Continued infection results in joint capsule and ligament dissolution, ending in fibrous ankylosis in 5 weeks in the rabbit model.94 Antibiotics, administered in this animal model before or at the time of inoculation, significantly reduced joint destruction.107 Irreversible changes occurred if the joint was not sterilized within 5 days of infection.84

Subacromial Septic Bursitis

Pyarthrosis of the glenohumeral joint may extend into the subacromial bursa. Most commonly, the infection occurs by direct erosion through the rotator cuff. However, 10% of the patients may have intact cuffs.122

Rarely, subacromial septic bursitis may occur in isolation, as the primary infection,112 or as a result of hematogenous seeding from a distant source of infection.23 The diagnosis is made by aspiration of the bursa for Gram stain and culture. Aspiration is performed in an area that will likely have the highest yield, usually where there is maximal tenderness and fluctuation (Fig. 35-2).

Septic Arthritis of the Sternoclavicular Joint

The sternoclavicular joint is an unusual site for infection, comprising 1% of all cases of septic arthritis.96 Sternoclavicular septic arthritis usually develops in patients with an underlying medical condition or predisposing factor, such as intravenous drug abuse,11,43,49 diabetes mellitus, rheumatoid arthritis, liver disease, alcohol abuse, renal disease, malignancy, steroid use, or infection at another site.17,96,123 However, infection may occur via a hematogenous route or by direct inoculation from trauma or subclavian vein catheterization in healthy patients. Ross and Shamsuddin96 recently reviewed the published reports of sternoclavicular septic arthritis and found 170 cases, 33 of which were associated with intravenous drug abuse. Serious complications such as osteomyelitis (55%), chest wall abscess or phlegmon (25%), and mediastinitis (13%) were common. S. aureus

was the most common pathogen, responsible for infections in 49% of the cases. Pseudomonas aeruginosa was responsible for only 10% of the cases; this represents a dramatic decline in incidence compared to older reports, presumably due to the end of an epidemic of pentazocine abuse among intravenous drug users in the 1980s. Before 1981, Pseudomonas was responsible for 9 of 11 cases of sternoclavicular septic arthritis among intravenous drug users. After 1981, 17 of 22 cases in intravenous drug users were caused by S. aureus. An earlier review by Wohlgethan et al.123 found S. aureus to be responsible for infections in 8 of 10 patients with rheumatoid arthritis, and three of four patients with renal failure. Of seven patients with a history of alcohol abuse, six were infected with streptococci.

was the most common pathogen, responsible for infections in 49% of the cases. Pseudomonas aeruginosa was responsible for only 10% of the cases; this represents a dramatic decline in incidence compared to older reports, presumably due to the end of an epidemic of pentazocine abuse among intravenous drug users in the 1980s. Before 1981, Pseudomonas was responsible for 9 of 11 cases of sternoclavicular septic arthritis among intravenous drug users. After 1981, 17 of 22 cases in intravenous drug users were caused by S. aureus. An earlier review by Wohlgethan et al.123 found S. aureus to be responsible for infections in 8 of 10 patients with rheumatoid arthritis, and three of four patients with renal failure. Of seven patients with a history of alcohol abuse, six were infected with streptococci.

The diagnosis of sternoclavicular septic arthritis is often difficult, and there is usually a delay between the onset of symptoms and diagnosis. Ross and Shamsuddin’s review found that the median duration of symptoms before diagnosis was 14 days (mean 29 days).96 In those 170 cases, symptoms most commonly involved pain in the anterior chest (78%), shoulder (24%), or neck (2%) long before other signs and symptoms occurred. Fever (more than 38°C) and bacteremia were present in 65% and 62% of the patients, respectively. The sternoclavicular joint was tender in 90%, and limited shoulder motion was noted in 17% of the patients.17,38,49,96 Joint aspiration was not feasible in most patients, but when performed, cultures were positive in 50 of 65 patients (77%).96 Computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) should be obtained routinely to assess for the presence of chest wall phlegmon, retrosternal abscess, or mediastinitis.

Septic Arthritis Superimposed on Rheumatoid Arthritis

Patients with rheumatoid arthritis are more susceptible to joint sepsis, compared with those without the disease. Their underlying chronic joint symptoms may delay the diagnosis of infection. Furthermore, the acromioclavicular joint may be involved, adding to the complexity of presentation. Gristina et al. reviewed 13 cases of septic arthritis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and found that most presented with a sudden exacerbation of the usual arthritic pain, abrupt onset of swelling, and increased joint temperature. Only 9 of 13 were febrile. The infecting organism was S. aureus in 12 cases and E. coli in 1 case.57 Several factors may predispose a patient with rheumatoid arthritis to infection, including a poor overall health status with coexisting morbidities (such as diabetes), the chronic systemic administration of corticosteroids and cytotoxic drugs, and the intraarticular use of corticosteroids.80 It has also been suggested that the synovial leukocytes of rheumatoid patients may have less phagocytic activity than normal, making their joints increasingly susceptible to sepsis.8 The grave complication of septic arthritis should be suspected in any patient with rheumatoid arthritis when the clinical course worsens acutely, and synovial fluid should be aspirated immediately for examination. Clinical signs and symptoms are variable and inconstant, and the sedimentation rate and roentgenograms are unreliable. Upon diagnosis, prompt surgical therapy and parenteral antibiotics must be instituted, because this complication can carry a high mortality rate.

Disseminated Gonococcal Arthritis

Unlike patients with nongonococcal shoulder sepsis, those with joint infections secondary to N. gonorrhoeae are generally young, healthy adults. Disseminated gonococcal infection is the most common cause of hematogenous septic arthritis of all joints. The most common clinical manifestation is a migratory polyarthralgia (70%). However, fever, tenosynovitis (67%), and dermatitis (67%) are commonly discovered on initial examination.86 Joint aspirate yields a positive Gram stain result in only 25% of the cases, and 50% of cultures test negative.87 Synovial fluid white cell counts are less than those for nongonococcal septic arthritis, but are still greater than 50,000 white blood cells (WBCs)/mm3. Urethral, cervical, rectal, and pharyngeal cultures have a much higher yield and should be obtained from any young, sexually active patient suspected of having gonococcal arthritis. The infection shows a rapid response to ceftriaxone, and the arthritis generally resolves in 48 to 72 hours. Surgical decompression is not needed in most cases, because joint destruction is rare.

EVALUATION

Clinical Characteristics

A general workup scheme for pyarthrosis of the shoulder is outlined in Figure 35-3. The typical clinical presentation of shoulder sepsis consists of complaints of pain, warmth, and swelling of the involved joint. A patient may exhibit a prodromal phase of malaise, low-grade fever, lethargy, and anorexia before the

acute onset.87 The acute phase usually consists of fevers and chills, with severe, incapacitating shoulder pain as the cardinal clinical manifestation. Physical examination reveals local signs of infection such as erythema, edema, tenderness, increased warmth, and limitation in range of motion (ROM). Previous reports have shown that fever is variably present (40% to 90% of patients), and when present may be low grade or transient.83,95 Rosenthal et al. noted pain in only 48 of 71 patients with septic arthritis, with limitation in ROM being the most consistent clinical sign,95 helping to differentiate a superficial soft tissue infection from a joint infection. Atypical presentations occur when there is chronic arthritis, immunocompromised states, extreme age, intravenous drug use, or low-grade prosthetic joint infection. Previous use of antibiotics as well as corticosteroids or nonsteroidal antiinflammatory medication may mask symptoms. These factors, plus the low index of suspicion for shoulder sepsis, often lead to a delay in diagnosis. Ward and Goldner, in a review of 30 patients with shoulder pyarthrosis, noted mild symptoms in the 27 adults and a mean delay to diagnosis of 46 days.121

acute onset.87 The acute phase usually consists of fevers and chills, with severe, incapacitating shoulder pain as the cardinal clinical manifestation. Physical examination reveals local signs of infection such as erythema, edema, tenderness, increased warmth, and limitation in range of motion (ROM). Previous reports have shown that fever is variably present (40% to 90% of patients), and when present may be low grade or transient.83,95 Rosenthal et al. noted pain in only 48 of 71 patients with septic arthritis, with limitation in ROM being the most consistent clinical sign,95 helping to differentiate a superficial soft tissue infection from a joint infection. Atypical presentations occur when there is chronic arthritis, immunocompromised states, extreme age, intravenous drug use, or low-grade prosthetic joint infection. Previous use of antibiotics as well as corticosteroids or nonsteroidal antiinflammatory medication may mask symptoms. These factors, plus the low index of suspicion for shoulder sepsis, often lead to a delay in diagnosis. Ward and Goldner, in a review of 30 patients with shoulder pyarthrosis, noted mild symptoms in the 27 adults and a mean delay to diagnosis of 46 days.121

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree