Scapulothoracic Arthrodesis

Brody A. Flanagin

Raffaele Garofalo

Sumant G. Krishnan

DEFINITION

Refractory disorders of the scapulothoracic articulation have been reported to result in debilitating pain and dysfunction that may require surgical management.

The most common clinical presentation, scapular winging, was first reported in the published literature in 1723, and several etiologies for scapular winging have been documented since then.14

Soft tissue operations (eg, pectoralis major tendon transfer) have had reported success in stabilizing the dyskinetic scapula in appropriate patients.

Despite successful clinical outcomes, a population of patients experience recurrent symptomatic scapular winging even after pectoralis major transfer.6,10,14

ANATOMY

The scapula is positioned over the posterolateral aspect of the rib cage, overlying ribs one to seven. It is suspended from the sternum by the clavicle anteriorly and plays an important role in positioning the upper extremity for proper function.

The lateral scapula includes the glenoid fossa for articulation with the humeral head.

The scapula provides an attachment for 16 muscles, which help maintain it in functional positions. It articulates on the thoracic cavity, allowing for elevation/depression, protraction/retraction, medial/lateral rotation, and anterior/posterior tilting.

A thin bursal layer separates the scapula from the underlying ribs.

PATHOGENESIS

Dysfunction of the scapulothoracic articulation has been well documented in the peer-reviewed literature.

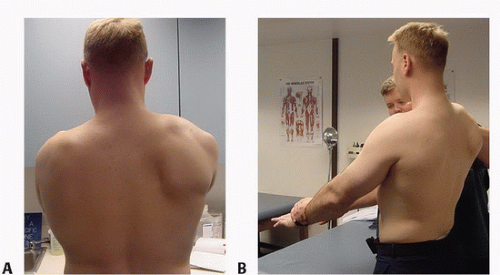

The most common manifestation of scapulothoracic dysfunction is symptomatic scapular winging7,14 (FIG 1).

Traumatic injuries to the serratus anterior muscle or the long thoracic nerve have been reported to cause symptomatic winging.7,8,11,14,19,20

Atraumatic etiologies, such as neuralgic amyotrophy, polio, and the muscular dystrophies, also may produce disabling scapular winging.1,2,4,5,8,10,15,16

Intolerable winging also has been demonstrated in association with other bony abnormalities (eg, rib or scapular osteochondromas and malunited scapular fractures) or soft tissue lesions (eg, scapular-stabilizing muscle contractures, muscle avulsions, and scapulothoracic bursitis).3,11,14

Recent authors have reported a significant incidence of scapular winging secondary to glenohumeral joint lesions such as rotator cuff tears and glenohumeral instability (especially posterior and multidirectional instability).18

The scapulothoracic articulation also is a potential source of debilitating pain in the shoulder girdle.

Several authors have documented the incidence of painful scapulothoracic crepitus (“snapping scapula” syndrome) and scapulothoracic bursitis.9,12,17,18

Painful crepitus can be due to interposed muscle, fibrous and granulomatous lesions, or bony incongruity associated with osteochondromata, fractures, scoliosis, or kyphosis.12

NATURAL HISTORY

Most patients who present with symptomatic scapular winging, scapulothoracic pain, or crepitus respond to nonoperative measures.

A subset of this patient population, however, experiences complex scapulothoracic dysfunction or pain refractory to conservative measures.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Patients presenting with scapulothoracic disorders typically complain of debilitating pain, shoulder dysfunction, or scapulothoracic crepitus.

Physical findings commonly include scapular winging, crepitus, alterations in normal scapulohumeral rhythm, or neurologic deficits.

Physical examination should focus on the resting posture of the scapula as well as its dynamic position.

FIG 1 • A. Moderate dynamic scapular winging demonstrated with slow forward elevation of the arms in the frontal plane. B. The same patient demonstrating marked medial winging with the resisted elevation at 30 degrees.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access