Risk Assessment and Exercise Screening

Edward M. Phillips

Jennifer Capell

INTRODUCTION

Beginning the Exercise Prescription Process

As discussed in Chapters 1 and 2, regular physical activity in the form of lifestyle exercise or leisure-time scheduled exercise confers numerous health benefits to the participants. As such, the public health goal for all adults to accumulate 30 minutes of moderate physical activity at least five days per week or to engage in 20 minutes of vigorous exercise at least three days per week is of paramount importance (1). Now that you are more engaged in the importance of counseling your patients to become physically active and to maintain their exercise programs, the question of safety to exercise arises.

Because of the overwhelming benefits of exercise, the universal hazards of inactivity, and the relatively rare serious side effects of exercise, the screening process should not present a burden to the clinician or prevent patients from initiating light- or moderate-intensity physical activity. (See Chapter 8 for discussion of exercise intensity.)

For the vast majority of your patients, the information that you as a clinician already possess about their medical history is sufficient to screen for safety to begin or increase exercise. This information includes a medical history of cardiac, pulmonary, and metabolic disease; known cardiac risk factors; signs and symptoms elicited during a routine physical examination and simple probing about their current level of activity—“are you physically active, at a moderate intensity at least 30 minutes per day, 5 times per week?” This question may be elicited as a “vital sign” at the clinical encounter to determine the need for your patient to initiate, increase, or continue physical activity.

In this chapter, we provide you with a systematic method of assessing your patient’s medical status to reduce the chance that your patient may risk injury or illness (particularly to his or her heart) by exercising. As you will see, almost all patients will benefit from exercise, but some, especially those patients with known disease, signs and symptoms, or risk factors for cardiovascular, pulmonary, or metabolic disease, may need to have certain modifications or restrictions placed on their exercise program.

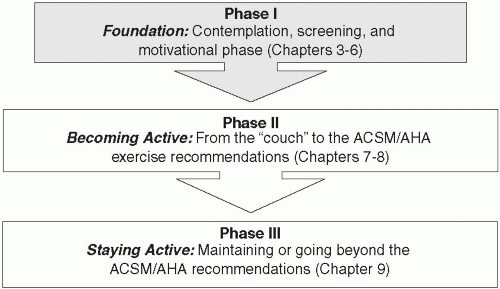

From there the more challenging aspects of mobilizing your patient’s motivation will follow. The combination of the assessment and evaluation of your patient’s safety to exercise and mobilizing motivation constitutes the Foundation Phase of the exercise prescription (Figure 3.1).

The process of making lifestyle changes from sedentary to active is a slow, but important aspect of your patient’s health. It is our hope that you will play an effective role in this healthy transformation. As you progress through this book, you will see that the process of prescribing exercise to your patient involves numerous stages before actually giving your patient the exercise prescription. In fact, we do not cover the prescription until Chapter 8. The preliminary stages in this process are crucial. As Figure 3.1 illustrates, this process begins with the Foundation Phase, in which patients need to be psychologically and motivationally ready to begin making lifestyle changes toward a more active routine. These subjects are covered fully in Chapters 4, 5, 6.

Risks of Sedentary Behavior

Before we present the possible risks of exercise, let’s begin with the question: “Is this patient safe to remain sedentary?” In most instances remaining inactive will harm the patient. Sedentary behavior is identified by the American Heart Association as a distinct cardiovascular risk factor (2) with prevalence twice that of smoking, hypertension, and dyslipidemia. While there are relatively rare serious risks to beginning an exercise program, there are universal risks from inactivity. Table 3.1 illustrates some of the risks associated with a sedentary lifestyle.

TABLE 3.1 Risks of Sedentary Behavior | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

Risks of Exercise

Continuing with our prevailing metaphor of using exercise as a medication to promote health as well as to prevent and treat illness, let us now explore the potential risks from using this “medicine” and present an effective and efficient means to mitigate these risks. Just as clinicians are aware of the risks or side effects of a prescribed medication, you must also be aware of the risks and side effects from prescribing physical activity. The risks of participation in exercise range from the most common—muscle soreness and musculoskeletal injury (please see discussion in Chapter 7)—to the most serious—myocardial infarctions and sudden cardiac death (3). Our primary focus in this chapter is on cardiovascular risks.

Cardiovascular Risks Associated with Exercise

Vigorous physical activity has been shown to acutely increase the risk of sudden cardiac death and myocardial infarction among individuals with both diagnosed and occult cardiac conditions (3). Further, atherosclerotic coronary artery disease is the overwhelming cause of exercise-related deaths in adults, accounting for one exertion-related death per year for every 15,000-18,000 seemingly healthy men (3). The relative risk of both exercise-related myocardial infarction and sudden death is most likely in individuals who are the least physically active and who engage in unaccustomed vigorous physical activity (3). Therefore, sedentary adults should avoid unaccustomed vigorous activity—they should begin with low- or moderate-intensity exercise and gradually increase their activity levels over time (3) (Chapters 7, 8, 9, 10 detail the appropriate progression of exercise to mitigate these risks).

Even amongst patients with known cardiac disease undergoing cardiac rehabilitation programs, the incidence of adverse cardiac events are rare: cardiac arrest = 1:117,000; nonfatal myocardial infarction = 1:220,000; and death = 1:750,000 patient-hours of participation (3).

Purposes of Screening

As with any “medication,” the risks or side effects can be minimized through appropriate prescription and progression. Therefore, appropriate screening of patients must be undertaken before beginning or increasing physical activity levels. The risk factors to be considered include cardiovascular, pulmonary, and metabolic conditions as well as specific conditions such as pregnancy, old age, osteoporosis, and others that we consider in depth in Chapter 13.

As we have just illustrated, in the vast majority of patients, the benefits of exercise far outweigh the serious risks of exercise and the universal risks of remaining sedentary. Further, by knowing your patient’s specific medical history, symptoms, and disease risk factors, and modifying his exercise program accordingly, you can further decrease his risk of suffering from an exerciseinduced cardiac event. The health screening process that we describe in this chapter enables your patient to be assessed in a systematic manner to determine his risk level for adverse medical events when exercising. While prudent screening is warranted for patients initiating, continuing, or advancing their exercise programs, this process should not present a barrier to participation in physical activity.

As the clinician, the algorithms presented in this chapter will help to identify factors that may 1) require preparticipation medical screening or exercise testing; 2) warrant a clinically or professionally supervised program or limitations on the intensity at which a patient is safe to exercise; or 3) (in a small number of patients) may exclude your patient from participation. Your responsibility is to follow a logical and practical sequence to acquire health information, assess risk, and provide the exercise prescription with appropriate precautions to your patient.

RISK ASSESSMENT

Self-Assessment

Patients may screen themselves to determine if a formal medical assessment is warranted by following the recommendation of the Surgeon Generals’ Report on Physical Activity and Health (1996): “previously inactive men over age 40 and women over age 50, and people at high risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD) should first consult a physician before embarking on a program of vigorous physical activity to which they are unaccustomed” (4). Please note the emphasis on the vigorous intensity. Initiating moderate-intensity physical activity does not require this screening.

Alternatively, the patient may also use a self-guided questionnaire such as the Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (PAR-Q; Figure 3.2). This self-guided, 7-question screening tool quickly identifies patients with conditions or risk factors that require further assessment before commencing an

exercise program. The PAR-Q is available online (at www.csep.ca), so your patients can complete the PAR-Q independently; however, you may find it beneficial to have patients fill out the questionnaire while waiting for their appointment with you. If your patient answers no

exercise program. The PAR-Q is available online (at www.csep.ca), so your patients can complete the PAR-Q independently; however, you may find it beneficial to have patients fill out the questionnaire while waiting for their appointment with you. If your patient answers no

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree